Enacted in 1977, the FCPA was born in the wake of an investigation related to the Watergate scandal that found that hundreds of American companies had spent millions in bribes to leaders of foreign governments in exchange for business favors. To restore public confidence in the marketplace and level the playing field for all businesses, Congress enacted the FCPA to formally penalize the perpetrators of these kinds of corrupt practices.

The FCPA primarily contains two sets of provisions that target different aspects of corporate bribery. The antibribery provisions prohibit the willful use of payments to foreign officials in return for unfair business advantages. American citizens and businesses, companies that have securities listed on U.S. stock exchanges or quoted in an over-the-counter market in the U.S., and certain foreign individuals and companies that conduct business within U.S. territories are all subject to the antibribery provisions of the FCPA.

By comparison, the recordkeeping and internal controls provisions, also known as the accounting provisions, are only directed at publicly traded companies, which are required “to make and keep books and records that accurately and fairly reflect the transactions of the corporation, and devise and maintain an adequate system of internal accounting controls,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). Targeting similar issues in corporate compliance, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) is often considered to have built on the requirements outlined in the accounting provisions of the FCPA. Enforcement of the FCPA is the responsibility of the DOJ and the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), which generally work in tandem to investigate and resolve most cases.

ENFORCEMENT ON THE RISE

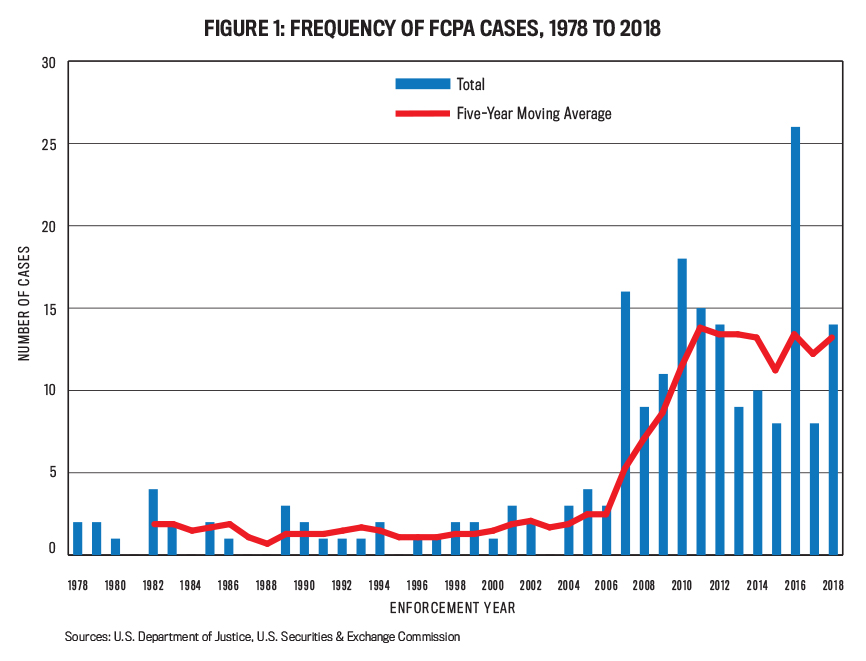

Although the FCPA has been in effect for more than four decades, a review of past cases reveals a unique pattern of enforcement (see Figure 1). Specifically, in the first 20 years of the FCPA, enforcement remained rather light, with an average of fewer than two cases per year. But enforcement ramped up around the year 2000. More cases were pursued, with greater penalties imposed. Between 2000 and 2018, more than 170 FCPA violations were pursued—an average of more than nine per year—representing roughly 80% of all FCPA cases since its inception. This suggests a major upward shift in the frequency of FCPA enforcement.

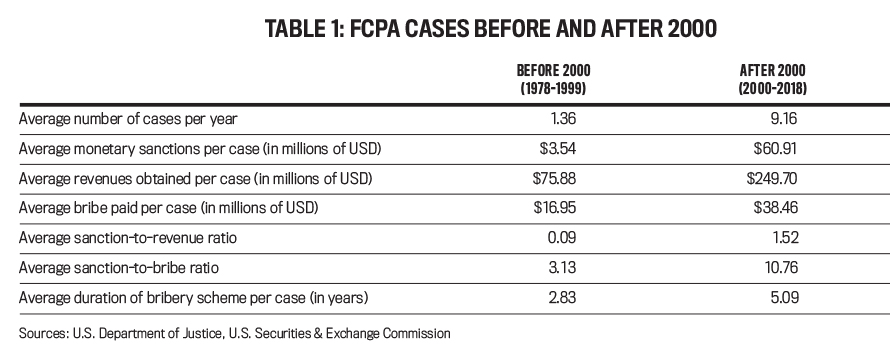

As Table 1 makes clear, not only was the FCPA beginning to be enforced more aggressively after 2000, the U.S. government began recovering a lot more money per case compared to earlier cases. The average monetary sanctions per case before 2000 was around $3.5 million but jumped to nearly $61 million for cases after 2000—an increase of more than 17 times.

Click to enlarge.What’s behind this sharp rise? I’ve found that it may be attributed to two nonmutually exclusive factors: (1) recent cases may involve larger bribery schemes that resulted in higher illicit revenues and disgorgements, and/or (2) the penalty for each dollar of bribe paid and revenue gained may have become more severe in recent years. My own detailed analysis of data from the SEC and DOJ, shown in Table 1, confirms these assumptions: FCPA enforcement has indeed intensified in the most recent two decades, as manifested by the larger number of cases pursued and tougher monetary punishments.

POSSIBLE EXPLANATIONS

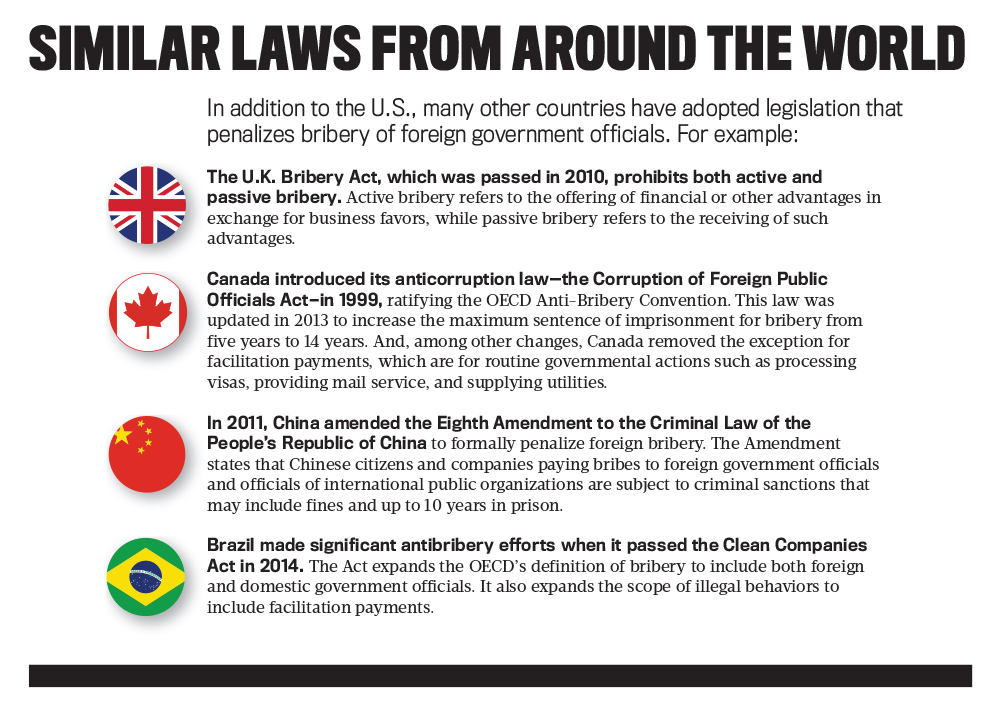

Several social, economic, and legal factors have been suggested to explain the heightened FCPA enforcement. To start with, the increasing globalization of the world economy has resulted in the rapid growth of multinational companies, which are susceptible to FCPA violations when entering and expanding in markets outside the U.S. Second, considerable effort has been made to enhance cross-border cooperation in antibribery enforcement within the international community, which helps to facilitate the investigation and resolution of FCPA cases.

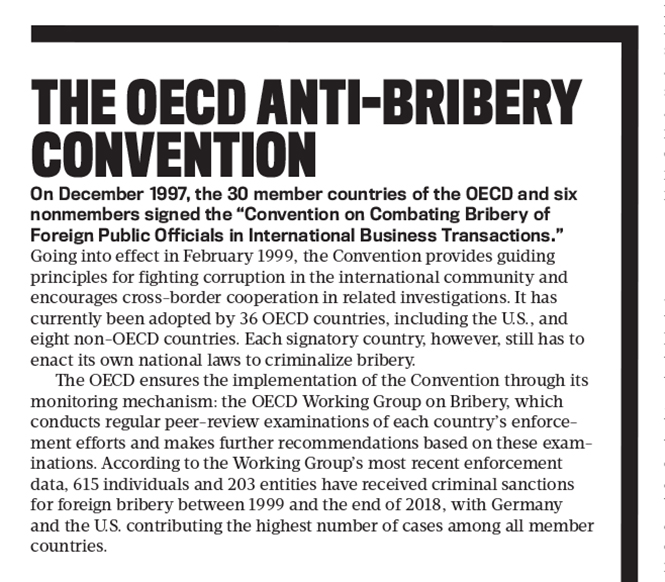

A prominent example of such effort is the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Anti-Bribery Convention, which was established in 1997 with the aim of reducing bribery of foreign government officials during international business transactions. (See “The OECD Anti-Bribery Convention”.)

Third, the FCPA was amended in 1998 to expand its scope to include a wider range of conducts and jurisdictions. As a result of these amendments, a larger number of companies and individuals became subject to the law. Fourth, the passage of SOX strengthened regulations over financial reporting and reinforced the importance of keeping accurate books and maintaining effective internal controls, which may have resulted in more companies engaging in self-checks and self-reporting of FCPA violations.

Lastly, U.S. enforcement agencies may be motivated to pursue FCPA violations more aggressively because they have the potential to bring in substantial fines. Other factors, such as the use of new FCPA resolution vehicles and increases in the SEC’s budget in recent years, may also have contributed to the heightened FCPA enforcement.

If the criminals’ tactics are getting more sophisticated, as many experts agree, then the two federal enforcement agencies, the SEC and DOJ, are undeniably working hard to keep pace. In 2010, the SEC’s enforcement division created a specialized unit dedicated to FCPA enforcement, recognizing the complex nature of the law and providing expert support to the existing task force. Two years later, in 2012, the SEC and DOJ jointly prepared and published a comprehensive resource guide to the FCPA to help businesses and individuals interpret the law (bit.ly/38f1WMg).

Meanwhile, U.S.-based multinational companies are actively seeking strategies to reduce their FCPA exposure. According to a Corporate Counsel Business Journal article, chief compliance officers are required to take on more FCPA compliance responsibilities and are subject to greater liabilities in cases of compliance failure. (See Jonathan S. Feld and Kara B. Murphy, “Make that Thirteen Labors: FCPA requirements present Herculean labor for compliance officers,” Corporate Counsel Business Journal.)

FCPA-related consulting services provided by accounting and law firms are also becoming popular with companies that operate in risky regions. For example, Deloitte’s forensic investigation department lists specialized FCPA consulting as one of its primary services. Accounting firms usually assist clients in designing compliance programs, performing due diligence, and conducting fraud investigations.

REACHING BEYOND U.S. BORDERS

Another noticeable trend of FCPA enforcement post-2000 is increasing litigation against non-U.S. companies that have securities listed on a U.S. stock exchange. Subsequent amendments, made in 1988, expanded the FCPA’s coverage to include “foreign firms and persons” who conduct illegal acts within U.S. territories. Therefore, the FCPA has a long reach that goes beyond U.S. shores, though for many years enforcement almost exclusively targeted U.S. companies. This is understandable given that enforcement agencies were still absorbing the law and forming their interpretations of it and cases against U.S. companies likely seemed easier to investigate and resolve.

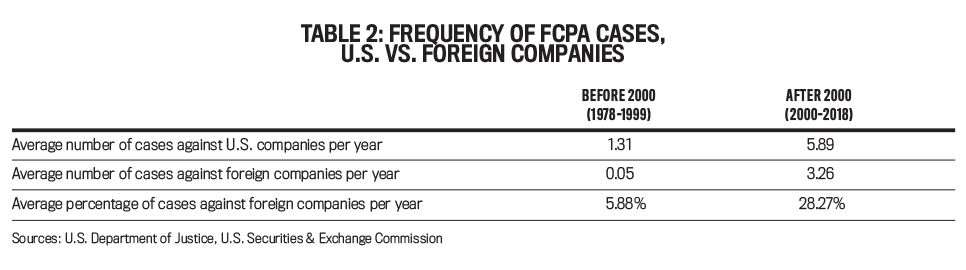

As Table 2 shows, the number of FCPA cases involving non-U.S. entities has averaged a little more than three per year after 2000—from practically none before then. Moreover, foreign cases as a percentage of total cases increased from an average of 6% per year before 2000 to 28% after 2000, representing a substantial change in the composition of FCPA defendants.

Click to enlarge.Yet whether or not the focus on foreign companies is intentional or coincidental, it’s hard to ignore the size of some of the FCPA-related penalties imposed on these companies—the highest of which reached $800 million. Table 3 lists the top 10 FCPA-related cases with the largest monetary penalties. These are headline cases that received substantial attention from the media and investors. Seven out of the 10 cases targeted multinational corporations based outside the U.S., including familiar names such as Siemens AG, Alstom, and Teva.

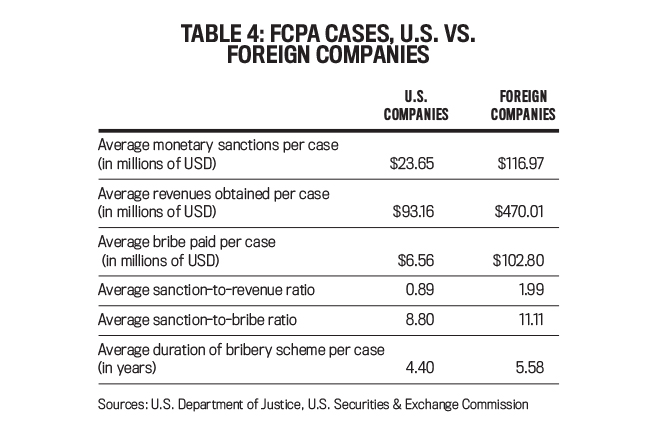

Table 4 shows that FCPA violations related to foreign companies involve significantly larger bribery payments, higher illicit revenues, and higher monetary sanctions compared to those of U.S. companies. Moreover, the sanction-to-revenue ratio for cases involving foreign companies—the rate of return for prosecutions, in other words—is significantly higher, consistent with far tougher penalties for bribery involving foreign companies.

Click to enlarge.In a 2012 New York Timesarticle, Leslie Wayne examines the scope of FCPA enforcement against foreign companies, in particular from the standpoint of foreign companies that have been subject to intense FCPA scrutiny. For example, Peter Y. Solmssen, general counsel at Siemens, admits that the FCPA is still a relatively new concept for European companies:

“U.S. companies have been living with this law a lot longer than European companies. It’s been part of their awareness. Our case was a real watershed. It woke up a lot of people in Europe. There had not been a lot of headline cases before that to make people sit up and take notice.”

In the same article, Lanny A. Breuer, an assistant attorney general with extensive FCPA prosecution experience, asserts that he maintains “an evenhanded approach in his pursuit of corporate bribe-payers.” When asked to comment on the skewed distribution of top settlements toward foreign companies, he said, “I am convinced that we are calling it down the middle. Some years we are criticized for it being too much American, other years that it is too much international. It is usually from the very same critics.” (See “Foreign Firms Most Affected by a U.S. Law Barring Bribes,” The New York Times, September 3, 2012.)

Moreover, in his 2014 book, The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in a New Era, Mike Koehler, a law professor and leading expert on the FCPA, points out that the U.S. probably also feels a moral obligation to penalize corruption by foreign companies, especially when the authorities in their home countries generally don’t, given the long history of U.S. antibribery legislation and enforcement.

IMPROVE YOUR COMPLIANCE

Current trends and developments in FCPA enforcement have important implications for companies operating in global markets. Here are a few tips on how to design and implement robust FCPA compliance programs to mitigate your own organization’s risk:

Understand your markets.Although corruption is a global issue, it’s more prevalent in developing countries and there are stronger demands for bribes when a company tries to enter these markets, resulting in higher FCPA risks. Therefore, strong FCPA compliance requires that companies have a comprehensive understanding of the markets they wish to enter—or currently operate in—to properly assess their FCPA risk.

How do you evaluate a country’s corruption level? One reliable source is the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) created by Transparency International, a nonprofit organization dedicated to fighting corruption, which interviews a wide range of experts and businesspeople to capture a country’s perceived level of public sector corruption. In addition, the World Bank publishes a data series called Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), which consists of six measures for country-level governance, including “Control of Corruption” and “Rule of Law”.

Understand your industry.Companies in certain industries are inherently more prone to FCPA violations due to the nature of their business. Public works and construction, utilities, real estate, oil and gas, and mining are listed as industries with the highest perceived level of corruption in a 2011 report published by Transparency International that ranks corruption in each business sector. Therefore, successful FCPA compliance requires a thorough understanding of how your industry operates.

Industry knowledge about FCPA compliance also involves understanding your industry peers’ FCPA activities. In recent years, the SEC and DOJ have adopted a proactive investigation strategy called “industry sweeps” to uncover potential FCPA violations, on the assumption that one or two bad apples within a particular industry may reflect an industry-wide pattern of malfeasance.

Once one company’s FCPA violation has been revealed, enforcement agencies will send out letters of inquiries, sometimes called “Hello There” letters, to solicit information and encourage companies to voluntarily disclose problematic business practices. The financial services, oil and gas, pharmaceutical and medical device, and movie industries have all been targets of such sweeps. It makes sense then that organizations should take into consideration industry-wide enforcement trends when designing their own FCPA compliance programs.

Be aware of what can trigger an investigation.When discussing the guiding principles of FCPA enforcement in its resource guide, the SEC suggested a few ways that an investigation of potential FCPA violations can be triggered, including tips from informants or whistleblowers, information obtained from other investigations, self-reports by companies, and public information sources such as media articles. Understanding these potential triggers could help your organization manage its FCPA exposure and reduce the risk of a costly FCPA investigation.

Self-report your potential violations.The DOJ and SEC’s FCPA resource guide from 2012 lists self-reporting, cooperation, and remedial efforts as important factors to consider when determining the appropriate resolution to FCPA matters. In 2016, the DOJ launched a one-year pilot program aimed at encouraging voluntary disclosure by offering reduced penalties and limited prosecution to companies suspected of violating the FCPA’s provisions. This program became permanent in 2017, and prosecutors have declined to charge at least 12 companies that self-reported their FCPA-related misconduct under the new policy. Given the substantial benefits of this approach, regular self-checks and self-reporting of violations should be an integral part of an effective FCPA compliance program.

Engage professional services.For companies that have major operations in multiple markets outside the U.S., FCPA compliance can be quite complicated and challenging. But help is available. Law offices and major global accounting firms have specialized FCPA compliance teams that assist clients in designing, implementing, and assessing anticorruption compliance programs. Forensic professionals at these firms, including legal and accounting specialists, can also help conduct internal corruption investigations and thus make significant contributions to the success of an organization’s FCPA compliance.

Clearly, we’re in a new era of FCPA enforcement defined by two major trends: First, the overall level of enforcement intensity has greatly increased, exemplified by the number of cases prosecuted and the magnitude of fines imposed. Second, while U.S. companies are still the targets of the majority of FCPA enforcement actions, non-U.S. companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges are being brought under the FCPA spotlight as well.

There’s no doubt that the FCPA is attracting increasing attention from policy makers, enforcement agencies, and businesses, as well as accounting firms and law offices. As a management accountant or other financial professional, you personally can make significant contributions to the success of your organization’s FCPA compliance—solidifying your legacy as a member of senior management or adding a feather to your cap as you make your way up the corporate ladder.

April 2020