The U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) recently got into the game when it released its proposal for the “Modernization of Regulation S-K Items 101, 103, and 105” in August 2019. While the proposal encompassed a wide range of amendments to existing rules, perhaps the most contentious of the amendments relates to the proposed new disclosure requirements around the company’s human capital, Item 101(c)(1)(xiii). (See “Human Capital Accounting—Frameworks and Guidance” at end of article.)

In an attempt to improve human capital reporting and disclosure, the SEC has proposed several revisions to the existing rule, reasoning that investors are “better served by understanding how each company looks at its human capital and, in particular, where management focuses its attention in this space.” The intent of the SEC proposal is to elicit material disclosures regarding human capital that allow investors to better understand this “resource” and to see how it’s managed through the eyes of company management.

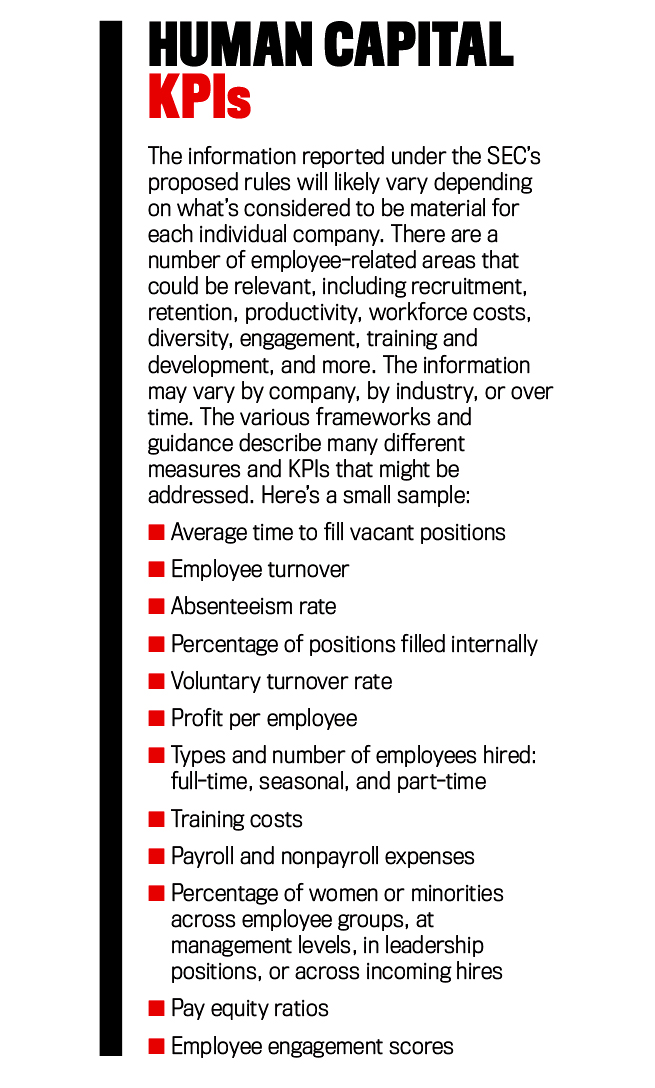

Currently, SEC registrants are required to disclose only the number of employees they have. The proposed changes would require registrants to describe their human capital resources, including any human capital measures or objectives that management focuses on in managing the business, to the extent such disclosures are material to an understanding of the business. The list of further disclosures for consideration may include, but is not limited to, the following (see also “Human Capital KPIs”):

- Measures or objectives that address the attraction, development, and retention of personnel;

- The number and types of employees, including the number of full-time, part-time, seasonal, and temporary workers;

- Measures with respect to the stability of the workforce, such as voluntary and involuntary turnover rates;

- Measures regarding average hours of training per employee per year;

- Information regarding human capital trends, such as competitive conditions and internal rates of hiring and promotion;

- Measures regarding worker productivity;

- The progress that management has made with respect to any objectives it set regarding its human capital resources; and

- The same disclosure requirements for registered issuers based outside the U.S.

As Asumi Ishibashi, Talent Management North America Lead at Willis Towers Watson, explains, the SEC proposal has come at a time when reporting on human capital is inconsistent, with companies using a variety of models and methods to manage and understand the value of their human assets. “There is an agreement that human capital is a key driver of performance,” says Ishibashi, “but we still lack a standard method of rigor in how companies are evaluating human capital. So, unlike the financial metrics that are used to assess organizational health, human capital metrics are treated separately, resulting in the inability of companies and investors to benchmark performance.”

REACTION TO THE PROPOSAL

For some, the proposal of the SEC to improve human capital disclosure is a giant step forward. According to public comments by David Vance, executive director for the Center for Talent Reporting, the proposed changes would bring human capital disclosure to U.S. public companies much sooner than expected if they went into effect, which is, in his words, a “very big deal...a game changer.” As to how this will affect the dynamic between the CFO and human resources (HR), he adds, “Most companies will rely on their heads of HR as well as accounting for guidance on what to include in their narrative on human capital. If for no other reason than risk mitigation, these leaders in turn will look to the human capital profession for guidance” (bit.ly/2TI8aQT).

For others, the question remains whether the proposed changes, and the range of further disclosure items for consideration, deliver on the insights and comparability investors want or simply pose an insurmountable task for preparers—one with possibly questionable benefit.

The end of 2019 marked the close of the proposal’s public comment period. A review of the submitted comments clearly points to the emergence of two camps: (1) those that think expanding the disclosure requirements in the audited financial statements is a necessary step in achieving transparent reporting around a company’s human capital assets and (2) those that see an added compliance burden that is not only redundant but will lead to more, not less, confusion among investors. In the first camp are investor advocates, think tanks, and industry groups; in the other, much of the financial management community.

Has the SEC gone far enough to satisfy investors, or did it go too far in the minds of America’s public companies? While that answer is still clearly up for debate, one thing that these two groups agree on is that the proposal hasn’t served to satisfy either.

According to the Human Capital Management (HCM) Coalition, the group representing institutional investors with $2.8 trillion in assets that initially petitioned the SEC to change its disclosure rules around human capital reporting, the proposed principles-based amendments and the potential subjectivity around materiality implies too much guesswork on the part of preparers and investors alike.

In the view of the HCM Coalition, the SEC hasn’t gone far enough. Its comment letter on the proposal noted, “We are concerned that relying exclusively on principles-based requirements may elicit generic disclosures that fail to provide decision-useful information and take substantial time to review and analyze.”

Aside from data collection and reporting pitfalls, the HCM Coalition is also concerned that a lack of well-defined rules on reporting key human capital information may open the door for companies that have suboptimal human capital performance to either pick and choose metrics that may paint a misleading picture of their performance or even omit critical information altogether.

Similarly, the Coalition is concerned that a company that has strong performance one year but suboptimal performance another year may choose to only report certain metrics in years where the results are the best, leading to holes in data and reducing comparability. “These potential issues could reduce investors’ faith in the markets,” the HCM Coalition notes in its comment letter, “and impair future capital formation—precisely the problems disclosure laws were enacted to mitigate.”

For Fiona Reynolds, CEO of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), the SEC has taken a step backward in the face of its own judgment. In her response to the proposed amendments, she notes that the SEC’s own analysis concludes that the comparability of reporting may be reduced under principles-based standards, which rely more heavily on the fallibility of managers’ professional judgment and experience.

Reynolds also points out that the SEC’s analysis supports a rules-based approach and that the benefits of rules-based requirements include increased comparability among companies, decreased information asymmetry, improved stock market liquidity, and lower costs of capital. She recommends, “Instead of eliminating rules-based disclosures, as the Commission proposes to do in several elements of the Proposed Rule, it should use its extensive experience reviewing and probing issuer disclosures to develop consistent rules on emerging, material topics, including line-item disclosure on access to and use of human capital resources as well as climate-related risks.”

Ultimately, she concludes, “the Commission should not rely only on the principle of materiality, as without additional specific disclosure requirements, the principle is not operative in practice. Pulling disclosure requirements back to the highest order principle of materiality and rejecting or minimizing the use of specific required disclosures, is an invitation to companies to tell their stories in a manner that makes comparison difficult.”

REPORTING CHALLENGES

Whether the numbers are based on prescribed disclosures or are principles-based linked to materiality, reporting on human capital in the financials comes with other challenges and issues for CFOs. According to the Committee on Corporate Reporting (CCR) of Financial Executives International, there are significant operational challenges to disclosing human capital information in Form 10-K. First, the CCR concludes in its comment letter to the SEC that it would be impractical and costly to provide human capital data within the 60-day 10-K filing timeline with the degree of precision that might be expected in a financial filing.

Second, the CCR notes, requiring this information in the 10-K would require executing disclosure controls and reviews at senior management and board levels under tight timelines established for financial reporting purposes. “Quickly collecting this data may be difficult because human capital information is often stored in varied systems across many jurisdictions.”

The CCR is also concerned about what human capital information companies would be expected to include in the 10-K. While it agrees with principles-based disclosures, based on materiality, the CCR is worried that the evolving nature of human capital information across companies doesn’t lend itself well to inclusion in the 10-K. More specifically, it asserts that the relationship between human capital information and financial performance is indirect and that many companies are still developing their understanding of this relationship and how it might be used for decision making. It adds, “We believe it will often be difficult to identify how a change in a human capital metric did or will affect a company’s financial performance.”

The CCR also points to the uniqueness of companies, suggesting that more is less when it comes to human capital reporting: “Even within voluntary disclosures…we believe the comparability of human capital disclosures across companies and even within industries may vary widely and could lead to confusion among users. We also believe it will be difficult for companies to provide consistent disclosures about what human capital information is material to their decision making, especially within the 10-K.”

Finally, CFOs are worried about disclosing competitive or sensitive information. “Companies may have material human capital measures used by management related to a specific geography, product line, or key talent group that is proprietary,” says the CCR. “For example, if a company had a material human capital measure related to a geographical center of excellence used to drive significant cost savings, disclosure may cause a competitor to try and replicate and/or compete for talent in the same geography.”

Thomas E. Roos, senior vice president and chief accounting officer for UnitedHealth Group Incorporated, tends to agree. He calls for maintaining the status quo, noting that companies already are voluntarily disclosing key performance indicators (KPIs) with respect to human capital in a variety of ways, such as at investor conferences or in proxy statements, earnings releases, external presentations, sustainability reports, or on their websites.

“We believe that companies have adequately met investor requests through these voluntary disclosures,” Roos says, “while balancing the need to protect competitive or sensitive information. Thus, no further rulemaking is necessary.” Additionally, insofar as certain disclosures may reveal competitive information, he notes that the proposed rule, as written, “could require companies to disclose proprietary and sensitive information which may result in competitive harm to companies.”

Finally, while much of the information is currently available, he notes, “the proposed disclosures could require significant effort and cause companies to incur additional costs in order to be able to track, summarize, and review the required human capital information, which would be contrary to the ongoing simplification efforts undertaken by the SEC.”

NEXT STEPS FOR CFOs

What do experts expect the outcome of the proposed rule changes to be, and what should be on top of the to-do list for CFOs?

According to Asumi Ishibashi, achieving the optimal type and level of disclosure is going to be a long journey. “Ultimately, having a standard approach across industries and different operating models is an important goal,” she says, “but it’s still quite a way off.” The return on investment (ROI) on human capital was historically focused on managing cost, she comments, and many companies are still thinking and managing that way. “Imposing a compliance framework on companies that describes the management and measurement of human capital has moved the needle forward, but we’re not there yet.”

As to whether the proposed rule change will see the light of day or is the precursor to even further disclosure requirements around human capital, Randel K. Johnson, Michael T. Dunn, and Mark A. Katzoff, from international labor law firm Seyfarth Shaw LLP, predict it’s the thin edge of the wedge. They caution registrants to keep a close watch. They write, “Without close attention by the business community to the rulemaking process, it’s possible that the disclosure requirements could be expanded, perhaps significantly, beyond the disclosure currently contemplated by the proposed rules.” They go on to warn, “If one reads the record discussed in the proposed rules and the comments submitted, there is no question, as night follows day, that certain groups will be pressing for much broader and intrusive disclosure requirements” (bit.ly/39LNZH2).

For CFOs and their finance teams, the immediate task is to start thinking about the potential impact of the proposed human capital disclosures on their information systems, control systems, internal resources, brand, and risk, as well as their relationship with their HR functions.

According to Brittney Newell, CFO at Expansion Capital Group, a specialty lender that has provided approximately $400 million in working capital to small businesses throughout the United States, investors need to understand the correlation between a company’s employees, innovation and productivity, and overall success, regardless of whether that company is registered or private. “There are hundreds of resources available to understand the efficiency and effectiveness of our human resource management systems.

And in the age of Big Data, advanced data analytics is allowing more accuracy and a better understanding of the ROI of human capital resources. This in turn has paved the way for better management and development of those resources.” For the CFO, she adds, the SEC’s proposed amendments will require an even greater understanding of how human capital impacts the success of companies. And with the advent of more clearly defined metrics of HR success, “I see CFOs becoming close partners and advocates of the HR function.”

At the same time, says Ishibashi, the proposed amendments support a compelling case for CFOs to think about financial, operational, and human capital metrics as a whole. “That’s where we’ll see greater collaboration between finance, HR, and IT going forward,” she adds, “whether it be partnering with HR to pave the way for benchmarks, or supporting their human capital strategy based on an understanding of the relationship between the workforce and financial outcomes of their companies.”

HUMAN CAPITAL ACCOUNTING—FRAMEWORKS AND GUIDANCE

A4S CFO Leadership Network, “Essential Guide Series: Social and Human Capital Accounting,” 2017 Developed for finance teams, this guide contains practical examples, suggested tools, and guidance for how social and human capital can be integrated into decision making, with a focus on developing resilient and sustainable business models.

International Integrated Reporting Council, “Creating Value: The value of human capital reporting,” 2016 This report shares developments in the reporting on human capital, identifying the benefits of human capital management and reporting—particularly when applying integrated reporting—as well as advocating for the development of an accepted approach to human capital reporting.International Standards Organization (ISO), “ISO 30414:2018, Human resource management—Guidelines for internal and external human capital reporting,” 2018, ISO 30414:2018 is a voluntary standard that provides guidelines for internal and external human capital reporting. Its objective is to “consider and to make transparent the human capital contribution to the organization in order to support sustainability of the workforce.”

Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), “SASB Conceptual Framework,” 2017 The SASB Conceptual Framework includes a dimension on human capital that “addresses the management of a company’s human resources (employees and individual contractors) as key assets to delivering long-term value.” It covers a multitude of issues, ranging from compensation, engagement, and diversity to working conditions, labor relations, safety culture, and more. The Framework guides the SASB in its approach to setting industry-specific standards for sustainability accounting.Human Capital Management Institute, “Human Capital Financial Statements” (HCF$) The HCF$ is a private-sector reporting framework and technology solution that values the business impact of human capital according to ISO human capital reporting standards. It aims to provide a standard method with which to measure, report, and disclose a company’s human capital and to help quantify human capital similar to financial statements.

©2020 by Ramona Dzinkowski. For copies and reprints, contact the author.

April 2020