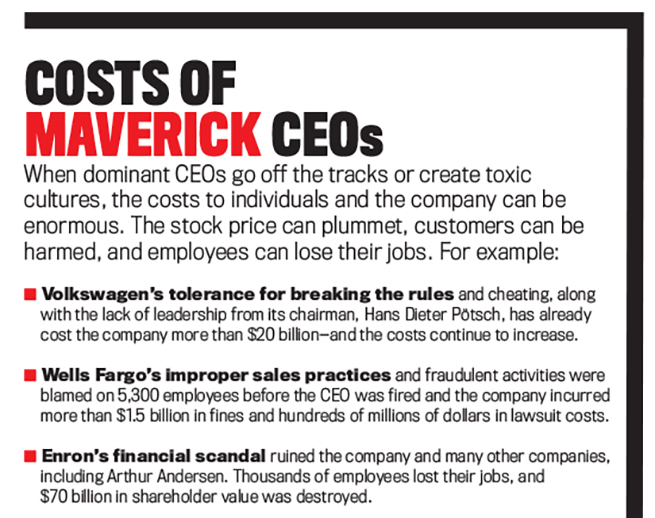

Elizabeth Holmes, CEO at Theranos, thrilled investors with her vision to change healthcare but then was charged with multiple counts of fraud and conspiracy in federal court after investors lost nearly a billion dollars of their investment in her company (see “Costs of Maverick CEOs” for more examples). Travis Kalanick’s leadership at Uber changed the city transportation industry, but it also led him to be ousted from the company he founded. One exasperated Uber board member proposed adding “No brilliant jerks allowed” to Uber’s list of cultural values.

The challenge for board members, investors, and employees alike is figuring out how to deal with dominant visionaries like these who are often brilliant, unpredictable, difficult to work with, and sometimes downright mean. In our work (with Tony Davila) on the best-selling book Making Innovation Work, which covered the development and implementation of an effective innovation strategy in a large organization, we realized there was one outstanding question—how to support the creative talent of brilliant leaders while still maintaining the necessary structure, systems, and guidance required for effective corporate governance.

In other words, how can you avoid getting in the way but ensure the rule-breaking CEO doesn’t go haywire and do something weird, illegal, or stupid? We wanted to better understand how middle and senior managers throughout these organizations could harmoniously survive and effectively deal with dominant, sometimes errant visionaries.

We reviewed our own experiences with dominant visionaries, talked to board members and senior executives with firsthand experience, and researched a long list of leaders who had proven to be both brainy and obstreperous. In our new book, The Brilliant Jerk Conundrum: Thriving with and Governing a Dominant Visionary, we share the findings and focus on seven revolutionary leaders and their companies: Steve Jobs and Apple, Elon Musk and Tesla, Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos, Larry Page and Google, Travis Kalanick and Uber, Jeff Bezos and Amazon, and Ken Lay and Enron (see “Seven Dominant Visionaries”). They represent a wide range of sectors that have seen incredible business growth as well as the spectrum of notorious visionary behaviors.

SEVEN DOMINANT VISIONARIES

STEVE JOBS: A founder of Apple in 1976, fired from the company in 1985, and rehired in 1997, Jobs led the company to amazing growth until his death in 2011 and is regarded as one of the great dominant visionaries of all time.

ELON MUSK: Since becoming chairman of the board of Tesla in 2004 and CEO in 2008, Musk has led the automobile company to tremendous growth. But he has also been at the forefront of controversy and confrontations with employees, government, competitors, media, and other stakeholders. He has a powerful vision for changing the world and shares it widely with overwhelming confidence, but many question if he’ll succeed. Those betting on his failure have left Tesla one of the most shorted stocks in the world.

ELIZABETH HOLMES: The 19-year-old Stanford dropout was going to change the world with a new blood-testing system, but it never worked. She put together an all-star board of directors and a billion dollars of investor money but led Theranos to collapse and to her many criminal charges for fraud and conspiracy for misleading investors, policy makers, and the public.

LARRY PAGE: A cofounder of Google while in his 20s, Page retained voting control of the company even when investors were brought in. But the investors wanted an experienced CEO (Eric Schmidt) to run the company. In 2011, Page was back as CEO and continued growing the company, leading it to great successes. A strong visionary, Page is dominant in all aspects of the company’s operations from products to culture.

TRAVIS KALANICK: Uber was founded on breaking rules. Kalanick’s business model was an attack on the taxi business—a highly regulated business in most cities. He typically ignored the regulations and plowed forward to great commercial successes. He was highly combative and controversial in both his company actions and personal behavior, leading to his being removed from leadership in 2017.

JEFF BEZOS: Bezos started Amazon in 1994 and has led its phenomenal growth ever since. Bezos is seen as a tough and demanding boss who has successfully proved all critics wrong when they doubted the long-term profitability and success of what has become the world’s most valuable company. Many consider him to be one of the great business leaders of all time.

KEN LAY: Lay merged companies in 1985 to become Enron. Under his leadership, Enron became the seventh largest U.S. company and Fortune magazine’s most innovative company, reaching $70 billion in value before becoming the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history in 2001. Its downfall led to senior executives going to jail, other companies also going out of business (including Arthur Andersen), and billions of dollars of investor losses.

How can a board and other corporate leaders tell the difference between an ingenious CEO on track to create groundbreaking innovation and one on a destructive path? When a CEO’s actions begin to damage the culture and long-term success of the company, what should the board do? Should it intervene? And if so, when and how? It’s tricky. This is the conundrum. The board can’t permit a toxic culture or the leader’s damaging actions to persist. But neither does it want to kill the creativity and innovation that are the key to the rule breaker’s success.

Two important lessons emerged from our discussions with board members, extensive research, and experience dealing with the conundrums of multiple brilliant jerks:

- The presence of an authoritarian trailblazer requires special handling. The traditional corporate governance principles are needed, but they must be supplemented with additional practices. With an inspired and highly controlling powerhouse at the helm, boards, investors, and employees need to be ready for a different journey.

- The best actions to govern, thrive, and survive depend on the type of visionary you’re dealing with. Dominant visionaries aren’t all the same. With some visionaries, there’s a risk of getting in the way and curtailing the value they could create. With other types, complacency is a huge mistake. Left unsupervised, their behavior could destroy the company.

WHO ARE THESE DOMINANT VISIONARIES?

Dominant visionaries show up in new Silicon Valley start-ups and also in more established companies. They can be the CEO and founder, or they can be other executives who aren’t afraid to exercise their power. No matter what their origin or position, they are charismatic leaders with a disruptive vision. Their magnetic personality and story attract investors, customers, and employees. They are all confident. But sometimes they have hubris and are overconfident. Though there have been some amazing successes like Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos, the history of these eccentric visionary leaders is mixed. While some of these leaders soar and achieve great success, others crash and burn.

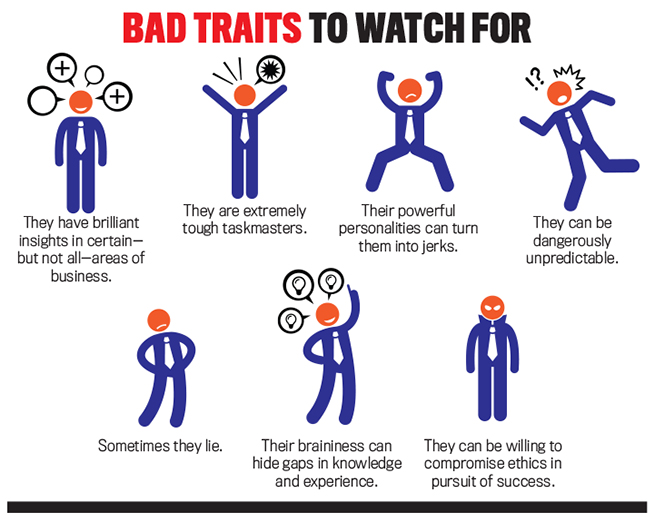

When we look at the spectrum of these extraordinary leaders, we see brilliance combined with stubbornness and a penchant for breaking rules. Some of these firebrands start out acting as role models but then their actions deteriorate into unattractive behaviors, sometimes turning them into jerks or liars or both (see “Bad Traits to Watch For”).

Many of these leaders often create a view that they have all of the answers and that the board, investors, and employees should just follow their lead. We call this the aura of executive omniscience.

EXECUTIVE OMNISCIENCE

When we looked at the recipe typically used by dominant visionaries to control their companies, we found three ingredients.

- Asymmetrical power. Dominant visionaries often have almost total control over their boards. Boards are supposed to be independent, but in many instances the CEO is also chairman and able to direct the outcome of all votes. In addition, dual-class ownership structures may provide the leader with absolute voting control (see “Dual-Class Ownership” at end of article).

- Cult of personality. Many of these leaders are visionaries with bigger-than-life personalities coupled with a compelling story of their unique potential to change an industry and maybe the world. They are quite persuasive and able to convince people to follow them. These leaders exude confidence in pursuit of their vision and may bully people to fall in line.

- Lack of transparency. By controlling the free flow of information, leaders are often able to block visibility to performance data that is critical to effective decision making and governance. When the board isn’t provided with essential information and is shielded from a clear picture of company performance, governance is significantly harmed.

The presence of any of these three elements doesn’t guarantee that there will be a problem. There are many companies that have had overwhelming success with one, two, or all three of these characteristics. But when these are present, it’s a signal there could be a problem. We generally recommend against dual-class ownership unless there is a sunset clause. Leading corporate governance practices emphasize the importance of the free flow of information to the board so that members can make informed decisions. And though charisma is often an important quality in a CEO, when it’s used to sway board members to lose their independent thinking and voting, board governance suffers. Thus, with dominant visionaries, additional board actions are often needed.

THE BOARD’S ROLE

The board has three core roles and responsibilities:

- Senior-level staffing and evaluation. This includes succession planning, compensation, and performance evaluations of senior executives.

- Strategic oversight. This includes the oversight of both the formulation and the implementation of strategy.

- Accountability. This includes governance practices, corporate behavior and ethics, and financial systems like disclosure and internal control.

These responsibilities can be fulfilled successfully by implementing leading board governance practices focused on board composition and board processes. The critical board composition criteria relate to competence, ethics, diligence, and independence. In addition, enhanced board practices relating to committee structure, productive meetings, information availability, and effective performance evaluation systems are critical. But regardless of the guidelines established, it’s important that the board be actively engaged in its serious responsibilities.

Boards must develop additional practices to deal effectively with the possible voting control that a dominant visionary, due to a strong personality, may exert through a dual-class structure and their control over the information flow. Board members must be active, and they must control the agenda rather than permitting the CEO to take that role.

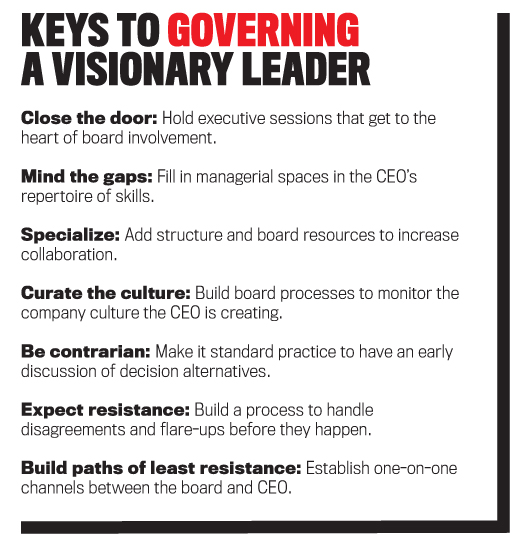

They must focus carefully on both board composition and processes. Board members surely must be competent, but they also must be strong, independent, and diligent. And they must ask the tough questions while facilitating collaboration and discussion (see “Keys to Governing a Visionary Leader”).

THE ROLE OF THE FINANCIAL EXECUTIVE

Financial executives are critical to effective governance practices in most corporations. All senior and middle-level managers have a responsibility to report actions and behaviors that are potentially damaging to the company’s future. The company must establish avenues for the safe reporting of any abuses. This can be difficult, especially when the bad behavior is by the CEO. Without such reporting, however, senior leaders and the board of directors may be ignorant of the abuses.

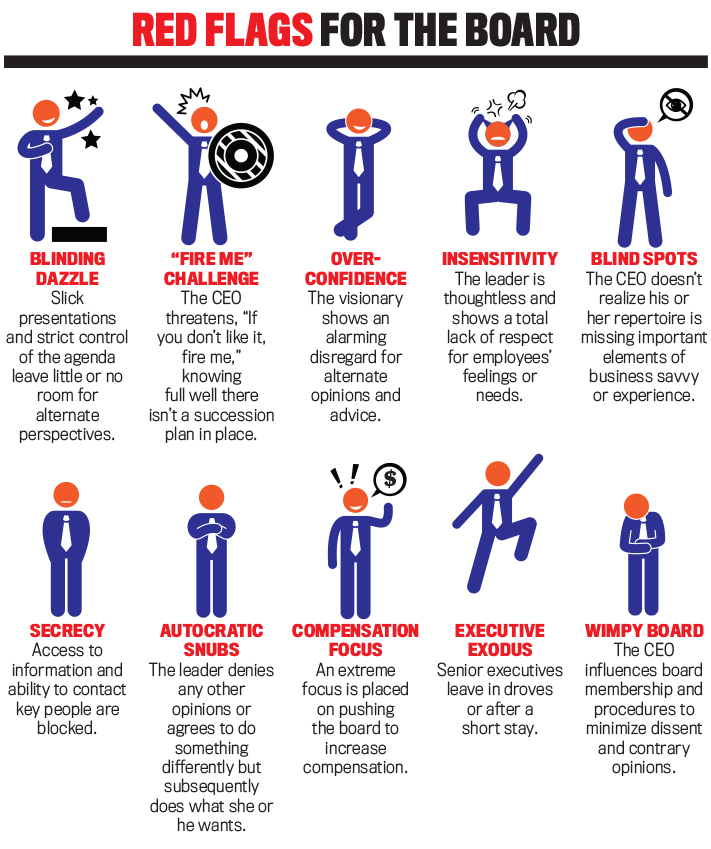

We found that when ethical and legal violations were discovered, many people knew about them but didn’t report them. All employees have a responsibility to report these ethical and legal violations, but financial executives have special responsibilities because of their roles in disclosure, internal control, accountability, and corporate governance. They should be on the lookout for evidence of a toxic culture that should be reported to the board.

Financial executives also must be aggressive in providing the board with guidance on abuses it needs to recognize (see “Red Flags for the Board”). Financial executives must be particularly sensitive to these in providing recommendations to senior leadership and the board to protect the long-term interests of the corporation.

KEYS TO SUCCESS

Corporate governance principles and practices are critical for long-term corporate success. For companies led by dominant visionaries, additional practices are necessary. Board members and executives told us one of the keys to success is knowing just what type of visionary you have to work with. We recommend building your governance approach informed by the dominant visionary’s behavioral characteristics.

- Brainiac quotient: All dominant visionaries are brainy, but not in the same way. For example, some are technology whizzes while others are fiendishly clever at designing new business models. It’s essential to know what type of genius you’re dealing with.

- Gaps in experience or skills: Even brainiacs have strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in experience. You need a solid appraisal of the leader’s blind spots.

- Propensity to break rules: All dominant visionaries are rule breakers, whether of laws, ethics, or social norms, but some can go to extremes. Knowing just how far the visionary leader will go is essential.

- Tendency to be a jerk: You need to ascertain just how much of a jerk the leader can be. Being obstreperous once in a while is probably fine, but constant jerkiness such as rude and abusive behavior toward employees is a problem.

- Ferocity: Headstrong leaders are always tough taskmasters. They expect everyone to put everything into attaining their goals. You should expect some ferocity in your leader, but be mindful that the trait can lead the dominant visionary to become a tyrant.

- Impulsiveness: You need to determine what can set off the boss or trigger reckless behavior. Many boards wish they had insight into the CEO’s tendency to jump off the rails before it happened.

Board members and executives warned us that confronting a dominant visionary needs to be done with care. Some leaders don’t want to listen to contrary opinions. They often don’t want to receive the oversight that boards of directors are supposed to provide—and don’t want to listen to suggestions from their senior and middle-level managers. Being confronted in a board meeting or executive session often results in a defensive reaction. And sometimes the CEO’s responses are downright nasty. Often, a one-on-one conversation outside of the boardroom or executive meeting is the right way to get things done.

Corporate governance principles and practices apply to all organizations, in all industries, organizations large and small, public and private, established or new start-up, closely held or widely dispersed. But we have found that the application of the core corporate governance principles and practices must be enhanced when there’s a particularly strong leader.

A word of caution: The goal isn’t to weaponize the board and constantly constrain the CEO. That could squash the value creation the brainy maverick is expected to bring. The role of the board, executive team, and investors is to support the disrupter-in-chief and provide just enough engagement and guidance to keep things from going wrong. Too much interference can destroy value; too little can destroy the company.

Companies and their boards need to use these new approaches to facilitate the tremendous growth that can be created by these leaders while simultaneously providing the governance necessary to minimize destructive behavior. This applies not only to high-profile CEOs but also to other senior managers who are dominant visionaries—and maybe to your boss also. It’s important that each of us takes responsibility for addressing these issues in our company ourselves—for the success of our company and for our individual well-being.

DUAL-CLASS OWNERSHIP

There have been numerous instances in business history where corporate founders have established multiple classes of stock so that unequal voting rights permit the founder to maintain corporate control through a special class of shares.

Dodge Brothers’s IPO in 1925 and Ford’s IPO in 1956 are early examples of dual-class systems established to keep family control while bringing in public shareholders.

It became increasingly popular with Google’s dual-class listing in 2004 and then was followed by Facebook, Groupon, LinkedIn, and others. The founders often have voting rights of 10 times or more what the public shareholders have. Snap made dual-class–share history by being the first company that issued nonvoting shares in its IPO.

Dual-class shares give founders control so they can resist undue shareholder pressure and pursue their vision. But it gives the founders disproportionate control and takes power from shareholders. To protect the long-term interests of the company, some companies establish an end date through sunset provisions that phase out the voting control over five to 10 years and restore a “one share, one vote” structure over time.

September 2019