For small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) in particular, the decision to invest significant time and money into a new technology can have severe consequences if the project fails to live up to its promise. Sometimes it’s useful to cut through the hype and reconsider potential IT investments from a simple cost-benefit perspective. Making the decision not to invest in a new technology or upgrade often can be the prudent choice. It requires thoughtful consideration and analysis.

Herein we have a success story of a family-owned retail business, which we refer to as RIL, located in the Fiji Islands, a developing nation in the South Pacific with a population of about 900,000 people. RIL began as a furniture manufacturer and wholesaler in the early 1990s and entered into retail in 1995 with one small shop.

By 2017, it had 22 shops spread across Fiji’s main island. Along the way, RIL expanded its retail product lines and entered other lines of business such as sawmilling, land development, and commercial property leasing. It has more than 600 employees and annual sales of more than US$19 million under the leadership of three family members who started the company and serve as the managing directors.

RIL is a household name in Fiji—people of all socioeconomic statuses, including the country’s prime minister, shop at its stores. Moreover, RIL was one of the first companies to be awarded the Gold Card certificate by the Fiji Revenue and Customs Authority (FRCA), the country’s tax department. The Gold Card recognizes “deserving FRCA customers” with sustained track records of regulatory compliance and describes them as “passionate and worthy citizens of our beloved country.”

FROM EARLY ADOPTER TO LAGGARD

More than 20 years ago, RIL was a technology leader among Fiji’s retailers. The company’s finance director, Mr. N, had convinced his fellow directors to purchase (what was then) a state-of-the-art accounting information system (AIS) with a point-of-sale (POS) module and barcode readers. RIL implemented this system at a time when most retailers in Fiji used basic manual systems.

Over the last decade, however, competitors have moved beyond manual accounting systems to implement on-premise or cloud-based enterprise resource planning (ERP) solutions such as EPICOR, Microsoft Dynamics NAV, Greentree, or SAP. RIL is no longer a technology leader in the country, lagging behind all but the small mom-and-pop retailers.

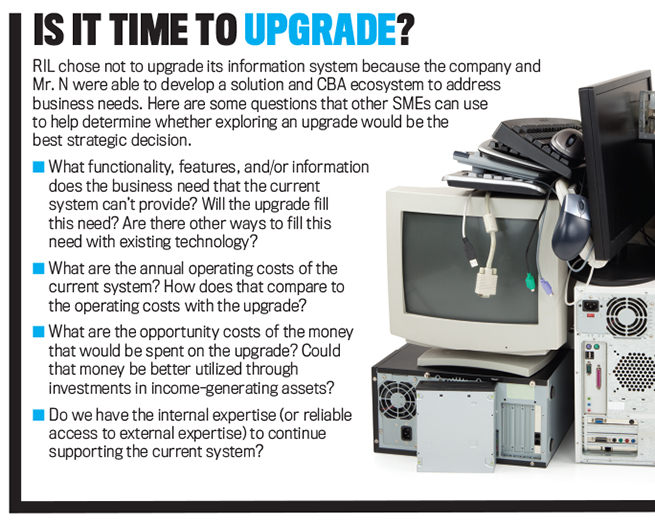

Yet RIL has steadfastly refused to upgrade or replace its 20-year-old system, even though software vendors and service providers repeatedly try to persuade the company otherwise and even though the original software vendor stopped supporting the product more than 10 years ago. How does a company with such complex and diverse operations across 20 locations, 600 employees, and one self-taught IT person remain successful and competitive with such an obsolete information system to support its operations? Mr. N believes that RIL has been successful thus far in part because of the decision to stick with its outdated AIS, not in spite of it.

We studied the company’s operations in 2017, expecting that once we understood its business processes and the limitations of its old AIS, we would identify viable ERP solutions and assist in the evaluation process. We knew that there would be challenges finding a cost-effective solution that would meet RIL’s needs and constraints, particularly because it operated within a developing nation.

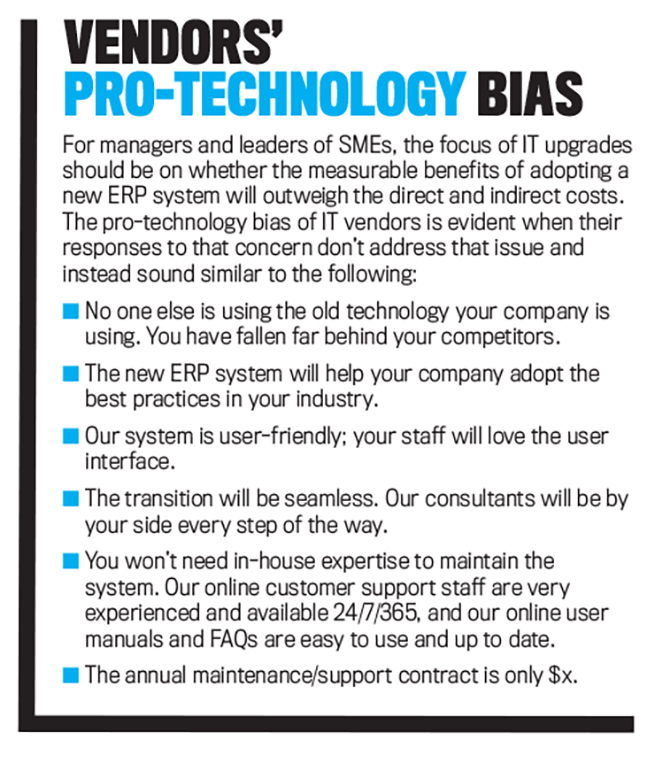

Admittedly, we went into the project without questioning our assumption that RIL needed a new AIS designed for SMEs. We ended the study, however, with a heightened awareness of the pro-technology bias that pervades much of the thinking in developed countries and an appreciation for the clear thinking that prevails within RIL. We found it to be an intriguing case study. The lessons we learned from studying RIL’s decision to not adopt a modern AIS or ERP system may be valuable to many other owners and managers faced with IT upgrade or adoption decisions, particularly those in family-owned businesses and SMEs.

THE STRATEGIC USE OF OLD TECHNOLOGY

In the mid-1990s, when many businesses in the United States were migrating away from their legacy information systems toward ERP implementations with software such as SAP R/3, most businesses in Fiji were still keeping manual books. When RIL started the retail business in 1995, it was common practice for retailers in Fiji to display items on shelves without prices, and shop owners would verbally determine prices for each customer based on what the shop owner thought the customer was willing to pay.

RIL broke from this practice to become one of the first retailers in Fiji to set prices on items and use barcode labels and POS cash registers integrated with a software package called CBA. RIL may have been one of the first companies in Fiji to adopt CBA, and the timing of this IT investment provided RIL a strategic advantage because it was able to expand operations geographically while maintaining control over pricing at each shop.

While CBA was an innovative choice for a Fijian retail business in the mid-1990s, it’s a dinosaur by today’s standards. CBA runs on DOS, Microsoft’s pre-Windows operating system that dates back to the 1980s. DOS doesn’t support mouse navigation; there are no clickable icons on a desktop, no multitasking, and no networking capabilities (beyond modem-based data transfers). DOS doesn’t recognize connections to USB peripheral devices, which means that RIL has to use outdated servers that can connect to outdated barcode scanners, keyboards, and printers. Mr. N has acquired a large inventory of old, outdated hardware and peripheral devices at a low cost, telling us with a smile, “Your U.S. trash is our treasure.”

The CBA vendor moved away from DOS in the late 1990s, rewriting the entire software system to run on Microsoft Windows. The new product was called Greentree. For many years, the CBA vendor tried to persuade Mr. N to move to Greentree, but Mr. N didn’t see the value given that CBA was functioning well and at a manageable cost. Recognizing that vendor support was dwindling, Mr. N increased his own knowledge of CBA to become less reliant on the vendor. When the vendor realized that RIL wasn’t going to switch to the new system, it allowed RIL to continue using CBA at no cost—but also with no support.

As best we can tell, RIL was the only client still using CBA at the time. Today, this old AIS, running on vintage hardware, connects RIL’s 22 retail stores using dial-up modems and old networking software to transmit daily store sales data to headquarters (see Figure 1).

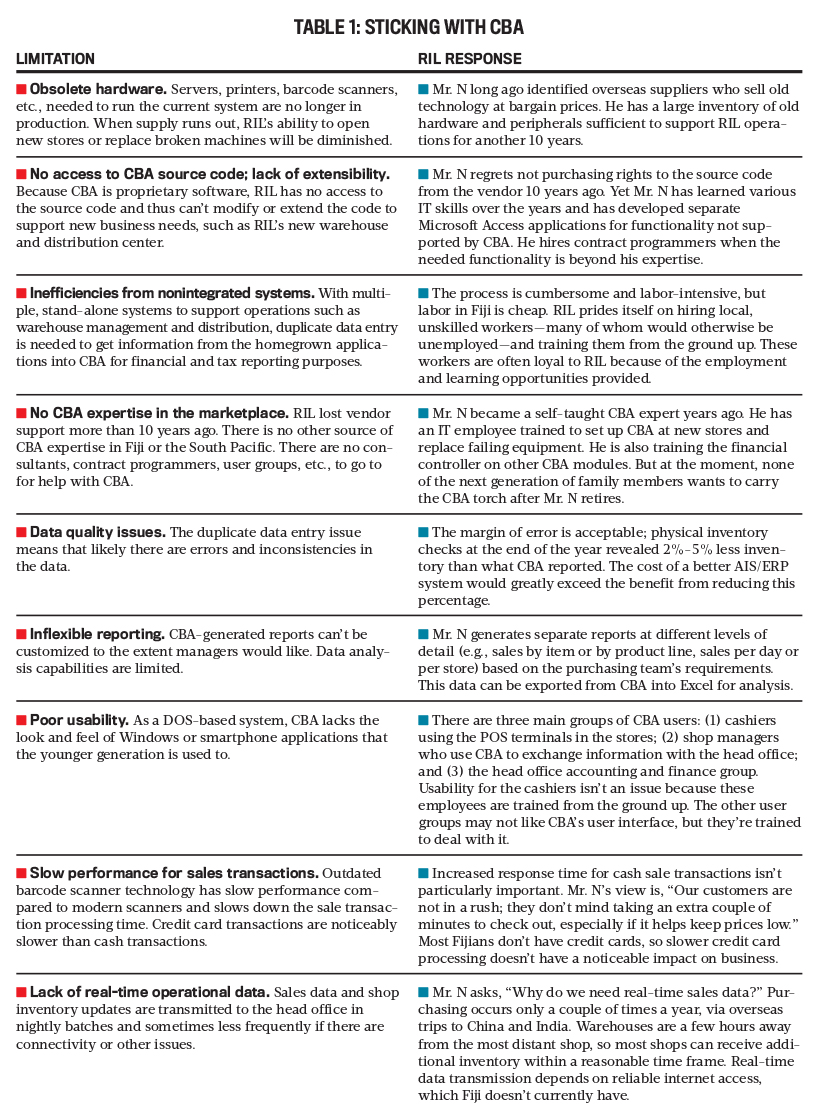

CBA has many limitations, but Mr. N points out that it has been operating reliably for more than two decades and provides the company with the basic information needed to run and grow the business (see Table 1). The positives from sticking with CBA include:

- There have been no network security problems. In part, this is because CBA is only “online” for a brief period each day to transmit data between headquarters and retail stores and because the old network operating system is scarcely in use and doesn’t attract much attention from hackers.

- There are no power-hungry operating systems or servers to overheat from lack of air conditioning in Fiji’s tropical climate.

- Fiji’s national infrastructure being what it is, there are intermittent internet connectivity problems that delay nightly sales data transmissions to the head office, but these delays have never interrupted a store’s ability to process sales because in-store sales processing doesn’t rely on internet connectivity.

- From an external auditor’s perspective, CBA’s modules-based accounting is transparent and easy to follow, and RIL has received clean audit reports each year.

- Most important, the operating costs are minimal. In 2016, RIL reported total IT costs, including internet, telecommunications, hardware, and software, of about US$55,000, which was 0.24% of annual sales.

The start-up costs for moving to a new on-premise AIS or ERP system would be high due to the need for new hardware, peripherals, and networking components in addition to the software acquisition cost and the consultant fees to implement the new system. (Recent vendor quotes show that the fees would be approximately FJ$3 million, or US$1.5 million.) In addition, the ongoing licensing and support costs would be close to FJ$500,000 (about US$250,000), and RIL would need an internal IT group with skilled employees to support the ERP system.

Moving to a cloud-based solution would reduce the start-up costs, but then daily store operations would require continual internet access, and broadband internet access isn’t yet reliable in Fiji. A new system would have to provide tremendous benefits to outweigh the cost differential, and no IT or business professional has yet been able to make a convincing business case for RIL to move away from CBA.

It’s clear that the limitations of CBA don’t outweigh the costs and risks of implementing a modern AIS or ERP system. In Mr. N’s view, the decision to stick with CBA provided RIL with a strategic advantage because the money not spent on IT freed up capital that was used to open new retail stores, expand product offerings, and enter new lines of business.

Sticking with CBA also helped RIL avoid the ERP implementation struggles and failures that many other Fijian organizations experienced. For example, one building supply company in Fiji changed ERP vendors four times over the last decade, costing the company more than US$4.9 million. Similarly, one of the government departments invested US$5 million for SAP over many years, only to pull the plug on the project.

LESSONS LEARNED

There are three main lessons from the success story of this family-owned business in Fiji. First, we learned to question our pro-technology bias. Going into the project, we were inspired to help RIL leverage modern technology to support its business operations. We didn’t think we would be recommending that RIL adopt a cutting-edge cloud-based ERP system, but we did assume that the company had outgrown its decades-old DOS-based AIS and was ready for a more robust, user-friendly, and extensible system. We weren’t expecting to discover that the use of obsolete technology has been a strategic advantage for the business. RIL has no IT problems that need fixing, at least for the time being.

Second, we gained an appreciation for Mr. N’s unwavering focus on basic cost-benefit assessments. In a situation where financial resources are scarce, good business owners and managers must stay keenly aware of the basic economic argument: Financial value must clearly exceed cost.

What surprised us was the sharpness and steadfastness of Mr. N’s focus. As RIL’s competitors adopt ERP systems, software vendors and consultants regularly pressure Mr. N to move away from CBA. RIL is the only known business still operating on CBA, yet Mr. N hasn’t been swayed by the hype surrounding ERP systems.

Just as important, however, is that he also hasn’t ignored the evolving IT landscape in the South Pacific. He reads, attends conferences, and networks with professionals in accounting, finance, and IT. He’s informed and inquisitive, open to reconsidering RIL’s position on CBA. But, as he told us, “I keep asking, but no one seems to be able to tell me what benefit we will receive from an ERP system that makes it worth the cost.”

Mr. N’s example provides support and encouragement to owners and managers of SMEs. Don’t succumb to the hype and peer pressure of adopting new IT solutions. Stay focused on what you, as experts of your business, know is important.

The third lesson relates to technology ecosystems. Many managers of SMEs around the world are like Mr. N in that they are skeptical of upgrading or adopting new IT when their current systems are working well and the costs of upgrading are significant. But in the case of SMEs with little or no in-house IT expertise, managers may not have a choice, other than to delay the change for a short while, because they’re dependent on the software vendor and related parties for support.

What we learned from RIL is that an organization can create its own “old technology” ecosystem if it has a leader who is self-reliant and willing to stand firm against the tide of IT changes. Mr. N couldn’t justify the move to an ERP system and wanted RIL to be able to chart its own IT destiny. The lag in ERP adoption in Fiji provided Mr. N with time to acquire the technology, skills, and resources to fortify the CBA system, and, as the ERP ecosystem in Fiji emerged and grew, Mr. N found an overseas supplier of vintage computing equipment and created a large stockpile. He became more of an expert on each CBA module and taught himself other IT skills so that he could create Microsoft Access databases to compensate for functionality lacking in CBA, such as warehouse management. He now is training RIL’s financial controller in the CBA modules needed to run the head office operations.

RIL has been able to extend the life of CBA by acquiring the supporting technologies and skill sets themselves. Creating an old-technology ecosystem is an alternative that RIL’s competitors likely didn’t consider. It has insulated RIL from pressures to adopt new and expensive technologies and has saved the company millions of dollars over the years, thereby increasing its bottom line and enabling it to build income-earning assets.

The lesson here is for managers to be aware of emerging technology ecosystems and take action—even counterintuitive, counter-cultural action—if they want their existing ecosystem to be robust and resilient. Mr. N’s resourcefulness is a hallmark of many entrepreneurs and small-business owners who have to make do with less, at least in the early days of their businesses. The RIL case demonstrates how important it is for SMEs to never lose this resourcefulness and instead to preserve it as a highly valued skill within the organization.

WHAT’S NEXT FOR RIL?

For the time being, the best decision for RIL is to continue supporting its CBA ecosystem. Yet the longevity of this ecosystem is highly dependent on Mr. N, who is likely to retire within 10 years. The looming question is what RIL will do when Mr. N retires. Will the replacement finance director understand how to keep the CBA ecosystem running? Will this person be similarly committed to the business’s success and work as hard to keep operating costs low by using old, cumbersome yet “good enough” technology?

Finding a replacement will be a tall order, especially as the younger generation of family members, educated abroad, are accustomed to Windows-based and smartphone user interfaces. They may not be particularly interested in learning the intricacies of CBA. RIL needs to formulate a strategic plan now for when Mr. N isn’t at the helm of the finance and IT functions. Adequate succession planning for key executives, especially in a family-run business, is paramount to the long-term viability of a business.

By developing his own, small CBA ecosystem, Mr. N created a solution that supports daily operations (albeit without any glitz or glamour) and furthers RIL’s growth and profitability goals because of its extremely low cost. Mr. N is one of the founding family members and managing directors, and his incentive to maintain the CBA ecosystem aligns perfectly with the directors’ incentive to make the business successful for themselves and for future generations of the family.

The contrast between Mr. N’s small CBA ecosystem and the broader ERP ecosystem in developed and developing countries is striking. The CBA ecosystem supports the basic operations of RIL; it’s cumbersome, but its cost is extremely low. ERP vendors are continually adding features and functionality to their products, and the supporting and complementary products and services change along with them. For example, there are consultants, programmers, user groups, and online resources to help with learning and using the various ERP modules.

We understand the market forces underlying the continual innovations and evolution of the ERP ecosystems, but we also see how businesses in developing countries—and small businesses in developed countries, too—suffer because their reliance on third-party vendors makes them vulnerable to the upgrades and changes dictated by those vendors.

CBA contributes to RIL’s success because of the dedication, work ethic, and cost-benefit focus of Mr. N. Imagine if those qualities could be cloned and incorporated into an ERP module. Unfortunately, AI hasn’t progressed that far just yet. There is no technology solution or IT-enabled change that can take the place of an owner-operator willing to do whatever it takes—regardless of the trends and fashions in the surrounding marketplace—to achieve the organization’s goals.

This study was funded by the IMA Research Foundation.

September 2019