The ongoing sagas of scandals in businesses across the world have turned the spotlight on the importance of an ethical culture, and the fines and other penalties for ethical misconduct are significant. In fiscal year 2018, the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) imposed $3.945 billion in penalties and disgorgement costs.

In the United Kingdom, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has imposed fines totaling $1.7 billion on five banks for failing to control their employees’ conduct, while the four largest banks in Australia have allocated more than $1.3 billion to cover the costs of recent scandals. Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, warns that institutions must not see astronomical fines for misconduct as “a cost of doing business” and that only “exemplary behavior” will restore trust in the industry.

Yet formal policies are insufficient to promote ethical business behavior. Leaders and employees may know the right thing to do, but they might fail to follow that course of action because of contextual pressures or an inability to translate good intentions into actions. By leveraging insights from behavioral science field research (such as the findings published at www.ethicalsystems.org), leaders can encourage employees to help them create an enabling workplace culture where poor behavior is no longer hidden or tolerated.

INFLUENCING HUMAN BEHAVIORS

Human dynamics, not formal policies, are shaping the social and psychological influences on modern workplace ethics. These influences include individual and group mind-sets, resentments, misunderstandings, interpersonal rivalries, role models, destructive communications, departmental and office politics, and a host of other issues. Since organizational culture is essentially about human behavior, an understanding of how personal beliefs, motivations, incentives, leadership styles, and organizational systems interact to trigger conduct risk is a new must-have insight. It requires a lot of reframing of old leadership models and developing new models of human motivation.

Behavioral ethics, a subset of behavioral economics, can provide leaders not only with a better understanding of how human dynamics shape cultural contexts, but also new, scientific ways to influence workplace behavior and nurture a healthy workplace cultural context. Applying behavioral science to workplace design is also in keeping with the recommendations of the Group of 30’s 2015 report Financial Stability Governance Today: A Job Half Done by Sir Andrew Large, former deputy governor of the Bank of England, whose insights offer potential solutions to the governance challenges facing the world’s largest financial institutions and the regulators overseeing the health of the financial system as a whole.

A behavioral science approach can predict the likelihood of how employees at every level will respond to various work pressures and situations, enabling managers to design specific interventions to promote the desired organizational culture and collective behavior. By addressing underlying causes of misconduct and people’s susceptibility to biases, evidence-based interventions can proactively support the intent of codes of conduct and breathe life into typically passive compliance initiatives, enabling organizations to better anticipate and manage conduct risk.

BEHAVIORAL AND CONDUCT RISKS

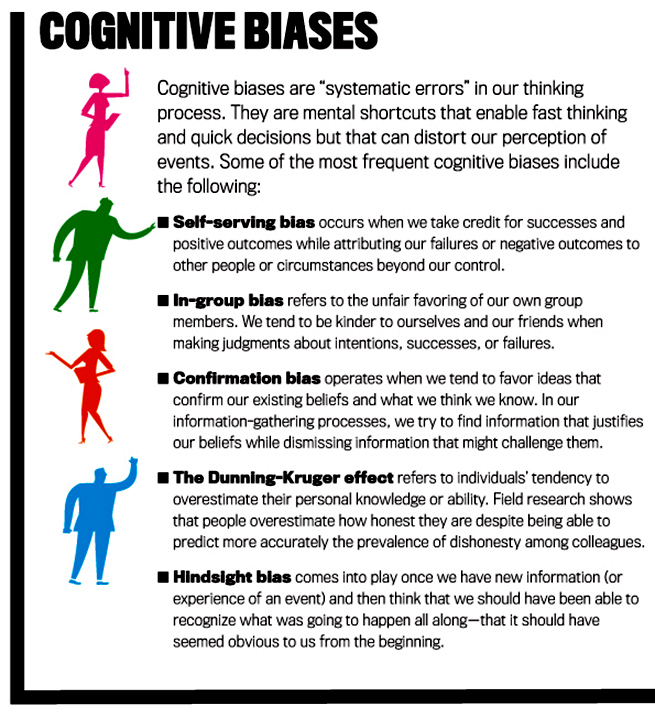

Behavioral science stems from a recognition that we aren’t always rational beings. We’re strongly influenced by our emotions and susceptible to cognitive biases affecting our judgment, causing the ethical aspects of a decision to disappear so that we only see what we expect to see. We have limited cognitive abilities; our brains use shortcuts, and the contexts in which we find ourselves have a stronger impact in shaping our decisions than our character (see “Cognitive Biases”).

An organization’s culture is the social context impacting employees. Designing policies to cultivate an ethical culture involves implementing and embedding better social cues, or “nudges,” to encourage the desired behaviors. Let’s take a look at some of the major conduct risks and how behavioral science can help address them.

Assumptions. Typically, organizations start from the assumption that employees will do the right thing, whereas science shows that most of us aren’t as ethical as we think; we compromise our values in specific contexts and under specific pressures—such as when we make decisions in groups—and don’t recognize that we’re doing so.

In fact, the pressure to “go along to get along” might be the strongest prevailing social pressure in organizations. Often, we operate on automatic pilot, doing our jobs based on what’s been done before, copying peer behavior “to fit in,” and taking shortcuts because we assume that we know what’s required. Yet the world is continually changing in interconnected ways, so taking our cues from what was considered acceptable in the past leaves us vulnerable to conduct risk.

Behavioral scientists have identified strategic organizational interventions called “choice architecture” that influence workplace behavior. Timely nudges, or prompts, are perhaps the most well-known intervention, taking the form of posters, screen savers, reminder texts, and other kinds of “just-in-time” notifications inserted at the point of decision making to highlight the right choice.

Together these interventions help to create a facilitating organizational infrastructure that encourages the desired behavior. Introducing emotional aphorisms or adages to influence daily behavior, such as “profits with principles” and “Our daily choices define us,” are far more powerful interventions than an emphasis on “do not…” signals. Metaphors and maxims evoke feelings that bypass critical thinking and transform abstract ideas into appealing behavioral mantras.

Behavioral science shows that positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions (i.e., nudges) achieve unforced compliance and influence employees’ motives and decision making. Self-interested goals are typically generated subconsciously so leaders can support their organization’s personnel in upholding ethical standards by providing a reminder or warning at decision time. Because organizational culture is transferred via language, aligning an organization’s internal dialogue and policies to support its stated values is a tangible way to nurture the desired ethical culture.

Motivations. Another behavioral science concept is motivated reasoning, which highlights how we tend to use reasoning not to get the facts, but rather to justify our existing conclusions. Motivated reasoning causes us to ignore information that challenges the desired outcome. Again, because this process occurs subconsciously, we continue to believe that we’re objective, whereas we’re using our reasoning only to construct justifications for our actions.

Incentive pay can also be a key driver of conduct risk. Regulators warn that commissions and bonus targets are a source of “motivated reasoning” and a systematic source of conduct risk in the finance industry, with the Wells Fargo fake accounts scandal the best-known recent example.

Research finds that when CEOs receive a large portion of their pay as stock, product recalls due to safety problems become more common because CEOs rationalize risky decisions to improve short-term gains in stock price. The 2014 U.S. Senate inquiry into General Motors’s failure to rectify a product defect revealed a prevailing cultural imperative at GM of “keep costs down.” The result was GM employees’ filtering out spending money from their decision-making process when determining how to address or correct the product defect.

Other triggers for motivated reasoning include command-and-control cultures, employees believing that the organization treats them unfairly, and instances where employees fail to engage or identify with the organization and its mission.

Behavioral science shows that workplace context can be so influential that we might engage in unethical behavior despite good intentions or do the wrong thing without realizing it because the context has given rise to “ethical blindness.” Volkswagen’s engineers who oversaw the fitting of a “cheat device” to ensure that their cars would pass U.S. Environmental Protection Agency vehicle emissions tests may have been suffering from ethical blindness. Had the engineers been required to personally affirm and sign a checklist indicating that the modifications they made were in line with Volkswagen’s ethical standards, they might have realized they were straying across an ethical and legal red line.

Rationalization. Our ability to rationalize our behavior is another systemic source of conduct risk. Research has found that when employees’ conduct clashes with their beliefs, they change their beliefs to support their conduct, failing to notice the switch. Unethical actions become acceptable after the fact as the perpetrators recategorize them as acceptable. Rationalizations work to eliminate guilty feelings and facilitate future conduct risk. Three of the most common forms of rationalization are:

- Denial of responsibility: “I know this is wrong, but [someone else] asked me to do it.” Employees who say this may be consciously bypassing policies or misbehaving and then rationalizing it as someone else’s responsibility.

- Denial of injury: “I know this is wrong, but no one will get hurt.” There’s no such thing as a victimless crime.

- Appeal to higher loyalties: “Our team needs this done.” This could indicate that the action requires justification for the employee to maintain self-esteem and thus is probably unethical.

Choice architecture interventions involve training employees to be alert to rationalizations and supporting their ability to make the right decision by providing ethical decision-making models that address various decisions and their potential impacts from multiple stakeholders’ points of view. By deliberately exposing the power of rationalizations in workplace training, leaders can forewarn and forearm employees to help them avoid potential ethical slippage.

Ethical Fading. Also known as “incrementalism” and “the slippery slope,” ethical fading results in individuals failing to recognize that their actions are escalating from lower- to higher-risk activities. Various factors can contribute to ethical fading. “Power distance”—or authority deference—inhibits us from noticing unethical requests, and a pressurized work environment encourages us to default to acting on automatic pilot, no longer fully conscious of how or why we make decisions. Amoral decision making, when we don’t contemplate the consequences of our decisions, is often pervasive in command-and-control cultures where the “just do it” mantra reigns.

Introducing interventions, such as a purpose-built ethical decision-making model that relates to the organization’s specific business context, checklists, and sign-offs, can help employees to become more mindful and less reactive in their decision making. Reminding people how they should act appeals to their emotional aspirations and enables greater commitment to ethical considerations, increasing the probability of good intentions being translated into actions. Other preparatory initiatives to offset ethical fading include asking people to repeat a mantra or motto; take an oath, such as the Dutch Bankers Oath; or personally sign off on recommendations and decisions.

Framing. How employees perceive or frame their behavior also shapes their ethics, and a great deal of unethical conduct results from mistakes of framing. Common frames include acting on the assumption that decisions need to be made either in the shareholders’ or the customers’ interests, or framing decisions as “business decisions” to avoid considerations of the negative personal impacts on others.

Applying choice architecture to these issues involves problem solving for a range of ethical scenarios that resonate with employees and that address the workplace challenges they may face. Then, discuss the various scenarios with them to analyze ethical actions—potentially in contrast to their initial reactions. Using potent decision-making models, such as the “Twitter test” or the front-page-of-the-newspaper test (i.e., would you feel okay if the course of action you’re considering were reported on the front page of a newspaper or shared widely on social media?), this discussion enables employees to straddle both their personal frame of reference as well as other stakeholders’ frames of reference.

Another opportunity is holding workshops or lunch-and-learn sessions to build employees’ ethical decision-making skills and assist them in becoming aware of unconscious biases and frames, such as the ubiquitous “If it’s legal, then it’s okay” and “Everybody’s doing it.”

Employee Treatment and Communications. Conduct risk also increases when employees’ accountability is unclear or if employees feel that they’ve been treated unfairly. Rather than dismissing employee concerns, as often happens, addressing and resolving the issue enables employees to perceive the organization as “fair” and builds an ethical culture. Research has consistently shown that when employees experience fairness, organizational misconduct decreases and employees are more willing to report ethical issues. New leadership models involve creating a culture of listening to nurture employee confidence and trust and demonstrating that there is zero tolerance for retaliatory behavior toward whistleblowers.

Reframing compliance communications also affects employee behavior. Compliance communications typically start from the assumption of the “rational actor” and the avoidance of personal risks, whereas more than 80% of workplace compliance choices are motivated by a moral sense of right and wrong. Therefore, rather than focusing on the negative consequences of unethical conduct, appealing to an individual’s belief in fairness and identity as an ethical person is more likely to be an effective strategy in reducing wrongdoing.

INTENTIONAL CULTURE MANAGEMENT

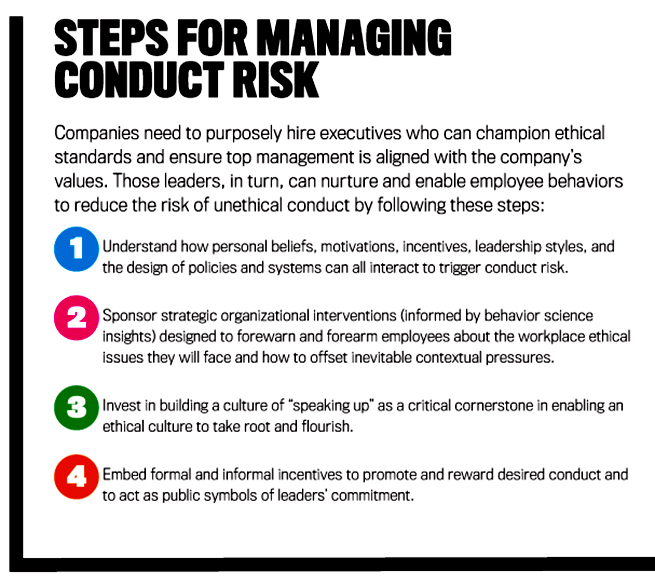

Ethical leadership is a process of social influence where leaders steer organizational members toward a high standard of behavior and hold the line when behavioral standards are breached. Good governance now requires a focus on how leaders’ traits and behaviors impact an organization’s ethical infrastructure.

Specifically, leaders must contribute to the good behavior of others through guidance, clear communication, and systems of rewards and discipline. Ethical standards become embedded only when senior managers champion them. It’s the organization’s leaders, not compliance managers, who have the positional power to create a macro “facilitating environment” appealing to employees’ intrinsic motivations and their self-concept as an ethical person.

With both personal and company reputations increasingly vulnerable to public scrutiny and assessment, all leaders need to become much more intentional and proactive in managing workplace culture and remain alert to how it spawns inherent conduct risks. Resetting the cultural bias of any large organization requires knowledge, skills, and commitment. Built on hundreds of small interactions, decisions, and daily actions, leaders need to influence both what people think and what people do.

Ethical leadership requires leaders to help their employees to continually improve and learn to respond to changes and challenges in appropriate ways. By building in daily reminders of the underlying issues and competitive pressures that accompany decision making, organizations that implement choice architecture enhance their employees’ ability to withstand social pressures and maintain ethical standards.

Culture change—and thereby behavioral change—requires an ongoing commitment to shaping a dynamic organizational environment that is responsive to changing societal expectations for appropriate business standards. Research by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) warns that the current predisposition of leadership to focus on its organization’s systems and policies overlooks the human dimension of ethical behavior.

Integrity depends on choices. By appealing to employees’ identities as ethical beings and employing the insights from behavioral science to design workplaces that encourage employees to act on their best intentions, ethical leaders will forgo business as usual to demonstrate that management accountants and finance professionals are capable of behaving ethically with or without regulation.

September 2019