From a business standpoint, loyalty programs increase customer retention, reduce marketing costs for acquiring new customers, influence customer purchases of the brand, and identify links between loyalty benefits and customer actions (as partial marketing research). From the customer standpoint, enrolling in loyalty programs provides feelings of reciprocity (getting something more than the original purchase), special recognition, and organizational trust and commitment in addition to benefits such as discounts.

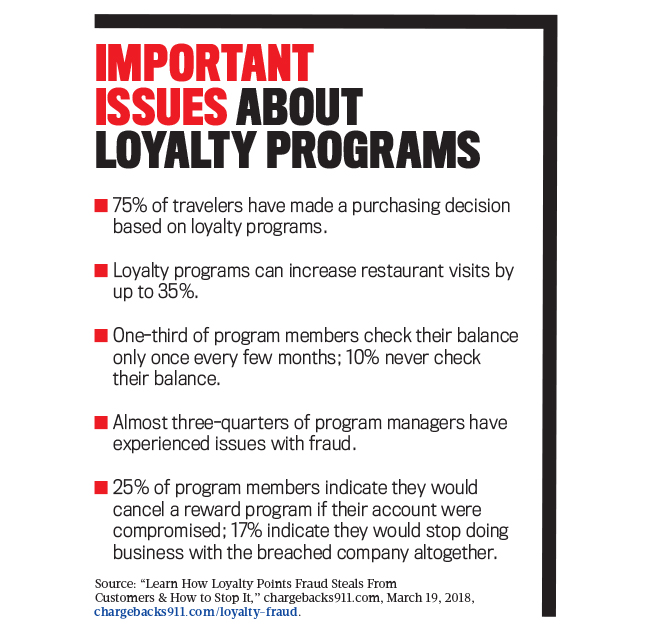

But there’s a not-often-recognized problem related to the value of loyalty programs: fraud. While 81% of Americans equate their accumulated reward points with cash, most consumers don’t regularly check their loyalty account balances. Furthermore, approximately 20% of reward members have never redeemed any of their accumulated points. These unused and unmonitored points have become a prime target for fraudsters to steal for their own use or to sell on the dark web. There are numerous different methods to perpetrating fraud in customer loyalty programs, and protecting your program against them similarly requires a variety of approaches and efforts.

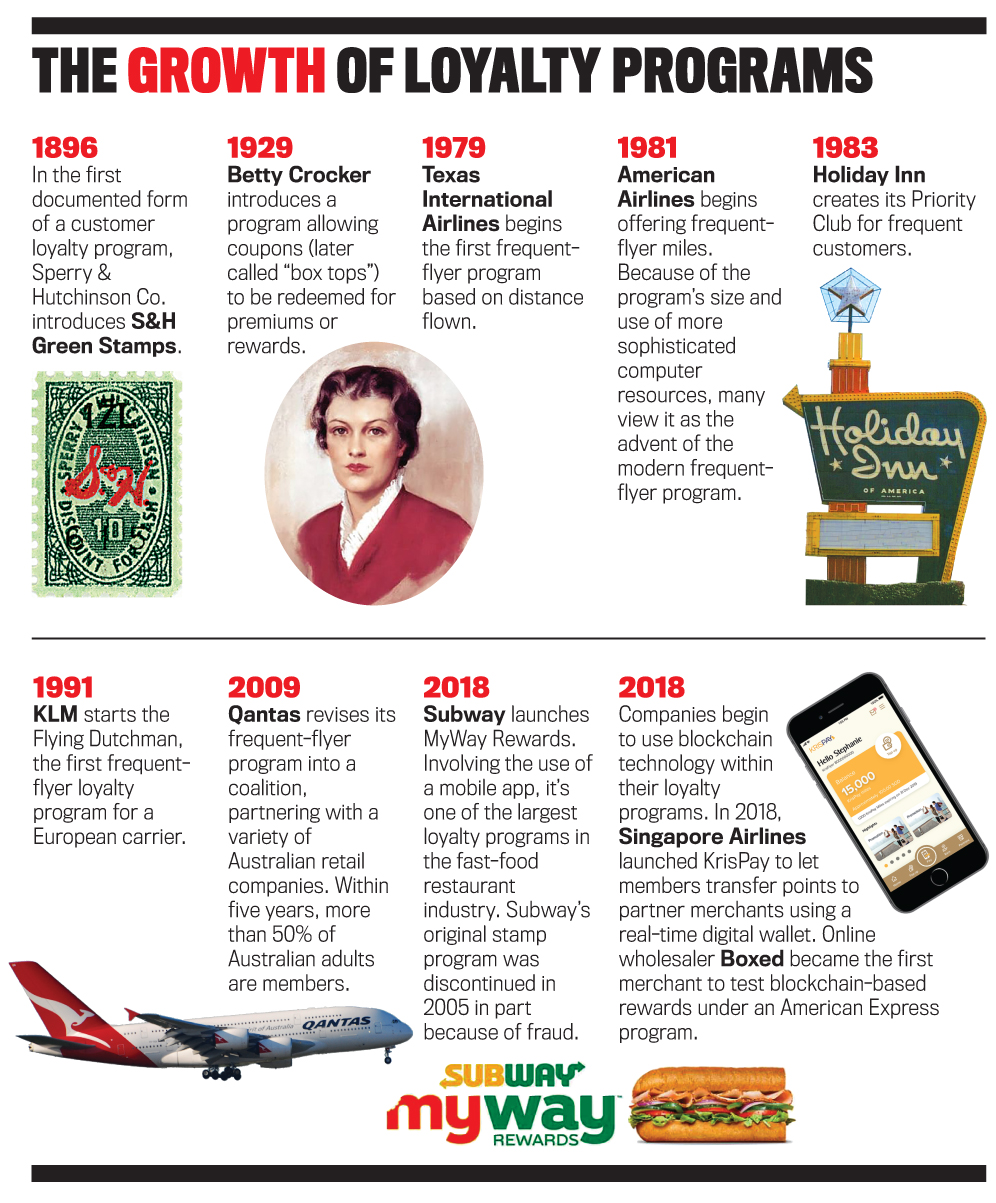

THE EVOLUTION OF LOYALTY PROGRAMS

Nearly every type of business—hotels, airlines, credit cards, gas stations, supermarkets, and more—has some form of loyalty program today. With so many programs available, it isn’t hard to believe that in 2015 the average household belonged to 29 programs or that in 2016 there were approximately 3.8 billion individual members of loyalty programs in the United States.

For years, many loyalty programs for smaller businesses have relied on paper cards that are punched or stamped when purchases are made. A punch or stamp can represent a single purchase or a purchase for a specific amount. These loyalty programs are simple to begin, inexpensive to produce, and easy to learn. But the cards are easy to counterfeit, are subject to cheating through invalid punches, and don’t provide the issuer with any usable customer data. Simple technology changes, like scanners, made punch-based card program fraud easy to perpetrate as people could easily generate and subsequently hole-punch their own homemade cards to obtain rewards.

Technology, though, has offered alternatives to small businesses that want to implement a loyalty card program but are aware of the problems with punch cards. Plastic cards are one alternative, as they’re much harder to reproduce than paper cards. But many more programs are moving from physical objects to a digital basis by incorporating the use of smartphone applications that provide both customer and business benefits. Mobile apps reduce customer wallet and key-chain clutter, minimize the potential of unauthorized punches, and provide valuable analytics that aren’t available with paper-based loyalty cards. These apps can also help a business personalize information about patrons that can be used to design differentiated rewards or services.

Today, the typical loyalty program allows its members to accumulate points for customer purchases in an online personal account. Points can be redeemed for rewards such as gift cards, travel, and meals. While they aren’t cash, the points do have real-world monetary value. For example, in the U.S. alone, there’s an estimated $48 billion in loyalty currency (see “Important Issues about Loyalty Programs”).

LOYALTY FRAUD

Loyalty programs provide a gold mine of information to businesses, but they can also enable fraudsters to access nuggets of this information with minimal effort. The sensitive information contained in reward program websites, such as personally identifiable information (PII), has significant value in the underground economy and can easily be used to commit identity theft. PII often includes details such as name, date of birth, email and mailing addresses, telephone number, credit card numbers, marital status, household size, and annual income.

Some estimates indicate that fraud has affected more than 70% of loyalty programs. Loyalty fraud can also occur through the theft of points or information or through gaming the system to generate undeserved points. Most consumers normally don’t review their loyalty points on a routine basis and don’t notice when those points have been compromised. Only when customers want to use their points might they find those points no longer exist.

The rules of loyalty programs typically require that the individual named on the account be the one who generates the points. Gaming the system in loyalty programs often means that the program member allows other people to use his or her loyalty card or number to generate points that accrue to the member. Such techniques are difficult if identification is required to access the loyalty account, but it may be extremely easy when points are acquired online or through an app.

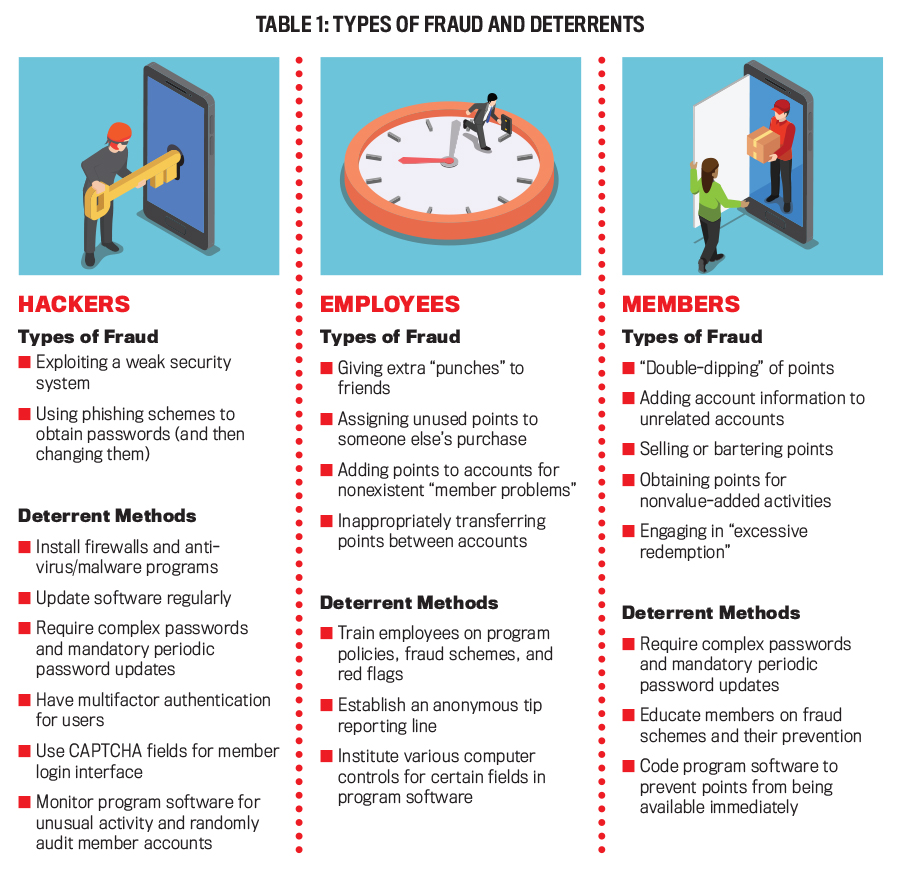

Perpetrators of loyalty program fraud can generally be categorized into three main types: hackers, insiders, and members.

Hackers

Hackers are outsiders (including members of organized criminal networks) who exploit a program’s security holes and weak customer passwords to steal accumulated reward points. These individuals employ methods such as phishing schemes or other forms of social engineering to collect information to hack into members’ accounts. Loyalty program currency is considered an easy target, primarily because of low consumer awareness relative to monitoring. Also, the security surrounding loyalty programs isn’t nearly as robust as that of other accounts that operate with real currency.

Stolen points may be used by the hacker to obtain free rewards. After a 2014 hack of the Hilton Honors program, one member’s account was used to pay for six hotel stays at Hilton properties; the corporate credit card associated with the account was then used to buy more reward points for the hacker. Hacked points may also become part of a triangulation fraud, which involves the loyalty customer, a hacker, and a third party (often a legitimate website or a “hacker bazaar”). In the Hilton Honors hack, many of the points drained from accounts later appeared for sale online at a fraction of their value: For instance, 250,000 points were sold for $3.50.

Insiders

Insiders are employees of the business that offers loyalty programs or others who have access and opportunity to scam the program. If punch cards are used in the loyalty programs, for example, insiders can easily give extra punches to their friends’ cards. Even with the advent of more sophisticated program devices, employees may be able to manipulate the loyalty point system.

If a customer isn’t a member of the loyalty program or forgets to use his or her loyalty affiliation when making a purchase, staff (such as call center agents, flight attendants, and check-in desk staff) might credit the purchases to their own personal accounts or to those of family members or friends. Depending on their employment level, employees also may have authority to adjust or add points to customer accounts as an accommodation in the event of a problem with the card or the point-of-sale terminal—something that could be abused by giving out unwarranted credits. And the ability to transfer points from one card to another could also be abused. It might be a necessary and legitimate employee activity when a customer’s card is lost or stolen, but it isn’t when points are transferred from inactive cards.

Members

Customers who belong to the program commit fraud when they attempt to “game the system” to their advantage. In “double-dipping,” a program member attempts to simultaneously redeem points over the phone with a company representative and through their account online. Or instead of redeeming points, members may try to fraudulently accrue points by attaching their reward account number to a purchase they didn’t make.

For many hotel reward programs, an account member is the only person who may earn points for the account and, thus, may only earn points when he or she is the one staying in the room. Yet circumventing this policy is quite easy—a member simply needs to book a hotel room in his or her name, including the account number, and then authorize someone else to be able to check in and pay for the room.

Most programs allow members to gift their points or awards to others, but selling points is often prohibited by the loyalty program’s policy. Thus, members who sell or barter their points are committing program fraud. Members have also been known to make purchases that generate massive amounts of reward points and then cancel the purchases—but not before the points are redeemed to obtain cash awards.

Some loyalty programs allow points to be earned for social media interactions such as retweeting, reviews, and referrals. To gain points, members may “overshare,” post insignificant reviews, or refer a large number of individuals who are unlikely to become loyalty program members. In these situations, members are obtaining value from the loyalty program by engaging in nonvalue-added activities for the business.

DETERRING FRAUD

While loyalty programs are expensive—investments in them may consume as much as 5% of sales—they’re implemented as a form of customer relationship management. Yet taking that attitude can lead to difficulties in fraud prevention and detection when businesses prioritize customer convenience over security. Many businesses have come to accept a certain level of loss from loyalty program fraud, and investments in fraud prevention and detection are seen as potential detriments to a positive customer experience.

When fraud is found and disclosed in loyalty programs, businesses face three major risks: a public relations risk relative to both the program and the brand; a financial risk relative to reimbursement for lost points or fraudulent redemptions; and a customer risk relative to lost customers or a disgruntled and vocal consumer group. One survey by Convergys Corp. estimated that a business can lose 30 customers after a single negative post on Twitter or Facebook. For businesses that prefer to take extra precautions, let’s take a look at some of the methods available to help combat loyalty program fraud. (Some types of fraud and deterrents are summarized in Table 1.)

Hacker Deterrents

Increasing security features is one of the best ways to deter hacking into any software, and loyalty programs are no different. Thus, the traditional methods of firewalls, antivirus or malware programs and scans, and regular software updates are mandatory.

Requiring complex passwords helps deter hackers. Also requiring members to make substantive changes to passwords periodically offers two types of protection: Changes help to keep passwords private and also compel members to log in to their accounts more frequently, which provides personal monitoring by the loyalty member.

Companies can also make use of multifactor authentication. Typical scenarios require two or three credentials: a knowledge factor (such as a password), a possession factor (such as a cell phone), and an inherent factor (such as a type of biometric verification). Location and time factors are two other possible credentials, such as GPS from a cell phone and time “credibility”—for example, a person can’t log in from Texas at 10 a.m. CST and from Hawaii 15 minutes later. Each separate factor adds a layer of assurance against hacking. Additionally, incorporating device recognition security measures should help flag any unauthorized access from a device that isn’t already connected with a member’s account.

Monitoring account activity helps detect fraud before it spins out of control. By utilizing software that analyzes account activity, suspicious transactions and redemptions can be flagged for further review. Logging all individuals who access an account, whether members or employees, helps to determine who initiated a transaction or change and at what time. This type of internal log provides the basis for investigating potential fraudulent activity. Any “atypical” behavior on an account (such as a change to login data) should generate a confirmation communication to the account holder to determine whether the change in question should be authorized.

Companies should invest the time to engage in random audits of member accounts and security reviews of the loyalty programs. They should test whether the software is performing as designed or whether the integrity of the software has been intentionally or unintentionally compromised. Software should be scanned for vulnerabilities such as network or system weaknesses as well as tested for the potential for penetration by hackers.

Insider Deterrents

A primary deterrent to insider fraud in loyalty programs is training, which should cover organizational policies and procedures on, as well as responses to, loyalty program fraud. Open discussion in training sessions also alerts employees that management recognizes employees might participate in loyalty program fraud and lets them know what will happen if such behavior is discovered. Organizations may need to establish an anonymous reporting line (or suggest the use of an existing one) so employees can communicate any potential fraud scenarios with appropriate management or independent outsiders.

Employees should be educated on loyalty program fraud to raise their awareness about potential fraud schemes and help them identify fake or compromised accounts. Red flags include an increase in employee access to, or time spent on, the loyalty program database; atypical variances in redemption activities; repeated unsuccessful attempts to log in to the rewards website; and unusual changes to member account profiles. An account that has numerous reward points transfers in a short period of time—especially to someone whose name isn’t on the account—may also indicate suspicious activity. Merchandise being shipped to an address not associated with the member’s account may also indicate the potential of fraud.

To prevent intentional erroneous data entry or unintentional errors by staff, companies should institute controls that establish boundaries (absolute limits) or value limits (that can be modified) for certain fields in the loyalty program software. For example, a boundary could be established that would only allow a periodic (such as daily or weekly) limit on the number of times that a social media share would result in points for a member. Or a software control could be designed so that any field intended for dollars would require a dollar sign to be physically entered.

Member Deterrents

Most businesses rely on passwords as their top form of authentication. But members usually don’t employ very strong passwords: A 2019 Verizon report indicated that 80% of hacking-related breaches result from weak or stolen passwords (vz.to/2POwMWl). To make matters worse, most people choose to use only a very limited number of passwords, making it easy to access other accounts once one account gets hacked.

Most members don’t access their accounts until they believe they’ve accrued enough points to redeem an award. Businesses may be able to entice members who need an incentive to log in more frequently by offering special promotions. Educating members about phishing schemes, breaches, and the importance of changing their password regularly should ultimately help prevent and detect fraud. By raising fraud awareness, the member can actively participate in combating fraudulent activity.

To help prevent members from “gaming” the system, loyalty program software could also be coded so that points aren’t immediately available for use. Such a time interval could deter scams using points from major purchases to collect rewards and then returning the purchased items. Similarly, if reward points are given for referrals, companies may want to institute a time lag to delay the issuing of those points to a member until a purchase is made by the referral. Such a program change would restrict the collection of points by a member who simply makes referrals to individuals who will never be value-added customers of the loyalty brand.

COMMUNICATION IS KEY

Loyalty programs have evolved tremendously, and many no longer focus solely on rewarding customer purchases. Programs are now viewed as customer engagement tools that are primary building blocks of data-centric marketing for organizations.

Because loyalty programs have become ubiquitous and valuable, they’re a target for fraud schemes externally and internally. As technology advances, security measures will be changed, and fraudsters will almost simultaneously discover new methods to dismantle those changed measures.

Adaptations to loyalty programs are generally made by a business to increase its profitability, fix a program problem, reduce fraud, and/or strengthen the bond between customer and brand. Customers will appreciate any change that reduces the potential for fraud in their reward accounts. That, in turn, will strengthen the customer/brand bond. The only way that a business can generate that appreciation is to provide ongoing communications about the change. Communication is the key to members’ understanding when a program change is made to help protect their loyalty currency, or that, without the change, would result in value disappearing from their account balances.

Experian’s 2019 Global Identity and Fraud Report indicated that half of the businesses surveyed had increased their budgets for fraud management during 2018, with 75% of businesses indicating that their online security had been improved (bit.ly/33m2bn1). Fraud losses and attacks also increased during that period, though, which might mean that businesses are making less-than-optimal investments. Accounting and finance managers may want to review, and possibly revise, some of the capital budgeting techniques used to evaluate investments in data loss prevention, especially relative to the more qualitative aspects such as reputation loss from cyberattacks on loyalty programs.

December 2019