Several dozen U.S. companies “inverted” or restructured and moved outside the U.S. between 2009 and 2017 to avoid tax liability. During the same period, according to estimates by the Federal Reserve, “trapped cash,” the levels of cash held by U.S. companies outside the U.S., increased to more than $1 trillion. Both strategies were successful attempts by U.S. companies to reduce tax burdens.

Ballooning levels of trapped cash and uproar over corporate inversions contributed to calls for corporate tax reform to make the U.S. competitive with the rest of the world. In December 2017, Congress passed the TCJA, instituting the most sweeping federal tax reform since 1986. Two key provisions of the TCJA were the reduction in corporate tax rates and the development of a new international tax system (see “TCJA Provisions on Foreign Earnings” at end of article).

U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin noted, “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act creates a historic opportunity for American companies to bring capital home from overseas to invest in our domestic economy and create jobs for hardworking Americans.”

Now that we’ve completed the first year under the new tax rules, let’s consider:

- Has the TCJA eliminated corporate inversions?

- How much of the trapped cash has come back to the U.S.?

- What have companies done with the repatriated cash?

- What can we expect companies to do with foreign earnings going forward?

REDUCING INCENTIVES TO INVERT

Before the TCJA, the combination of a high corporate tax rate and the differential treatment of income earned in the U.S. vs. outside the U.S. provided a powerful motivation for U.S. companies to restructure to reduce taxes. A corporate inversion, as defined by the U.S. Treasury, occurs when a U.S.-based multinational corporation restructures so that the U.S. parent is replaced by a foreign parent and the original U.S. company becomes a subsidiary of the foreign parent. For example, if a company restructured to move to Ireland where the tax rate is about 12.5%, the savings could be very significant. Companies with large levels of unrepatriated foreign cash would benefit further by permanently avoiding the additional tax on these earnings.

While there have been examples of inversions since the 1980s, the practice became increasingly common beginning in 2009. The Federal Reserve estimates that at least 30 inversions were announced or completed between 2009 and 2014, including Burger King’s acquisition of Tim Hortons and relocation to Canada and Medtronic’s acquisition of Covidien and move to Ireland. In most inversions, corporate headquarters moved to the low-tax country while many business activities remained in the U.S. On April 4, 2016, the U.S. Treasury announced regulations under Internal Revenue Code sections 304, 367, 956, 7701(l), and 7874 aimed at deterring inversions and other tax avoidance strategies. The regulations seemed to reduce—though not eliminate—the practice.

The TCJA reduction in corporate tax rates and move to a territorial system of taxation removes the primary incentives for inversion since U.S.-based multinational companies are taxed only on domestic profits and now are taxed at a significantly lower rate.

Yet while the TCJA seems to have dramatically reduced the incentives to invert, there may still be advantages to companies considering relocation to a country with a tax rate well below the current U.S. rate of 21%. In March 2018, Ohio-based Dana Inc. announced it planned to acquire part of GKN (the Driveline Division) and move its headquarters to the United Kingdom. This announcement followed an offer by Melrose Industries to acquire GKN. Dana’s CFO noted that, “The Company expects that even under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, this move will reduce its tax liability by around $600 million over several years.” But this inversion never materialized since GKN’s board of directors accepted a new offer from Melrose Industries several weeks later.

HOW MUCH TRAPPED CASH HAS BEEN REPATRIATED?

The TCJA transition to a territorial tax requires companies to pay a onetime “deemed repatriation” on foreign-held earnings generated between 1986 and 2017. Note that foreign-held earnings may have been reinvested in fixed assets, used in business activities, or invested in liquid assets such as U.S. Treasury bonds. Trapped cash refers to the liquid assets held by U.S. companies outside the U.S. that were typically not repatriated because of tax implications. The TCJA removes the disincentive to repatriating cash, and, during 2018, data from U.S. current accounts suggests an estimated $600 billion of the approximately $1 trillion in foreign-held cash was repatriated to the U.S. Whether or not the companies physically bring the cash back to the U.S. is irrelevant under the TCJA. The “deemed repatriation” tax is levied regardless of whether the earnings are actually repatriated.

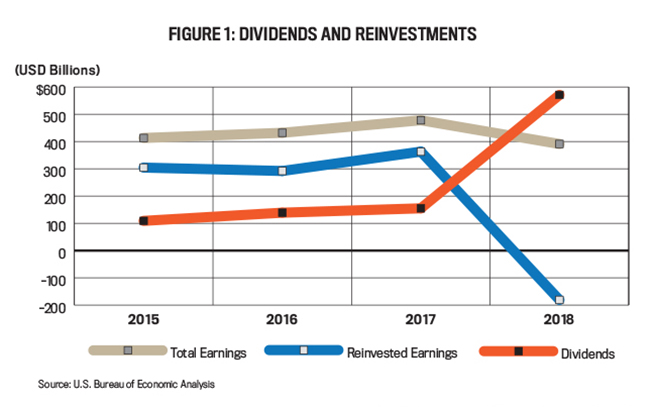

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reports on the level of foreign earnings of U.S. multinationals and also shows the portion that’s repatriated in the form of dividends and the portion reinvested in foreign affiliates. In 2018, reinvested earnings is a negative value in the first two quarters because U.S. companies withdrew foreign earnings following the implementation of the TCJA (bit.ly/2FjsNeK).

Figure 1 shows longer-term trends in reinvested earnings and dividends and highlights the impact of the TCJA in 2018.

HOW HAVE COMPANIES SPENT THE REPATRIATED CASH?

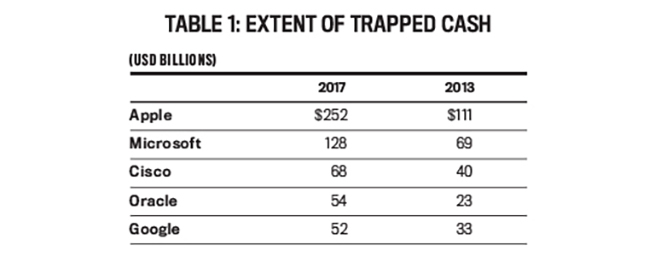

Companies repatriating cash may choose to use it for myriad purposes including acquisitions, capital expenditures, debt repayment, dividends, share repurchases, and employee hiring and bonuses. Additionally, companies may choose to use some of the cash to pay the tax on the earnings deemed repatriated. Results are preliminary since it will take a while for all cash to be repatriated and put to work. Here we focus on five companies with the most cash held outside the U.S.: Apple, Microsoft, Cisco, Oracle, and Alphabet (Google). Table 1 depicts the extent of trapped cash held by these companies and the significant increase since 2013.

Proponents of the TCJA suggested that repatriated funds and lower tax rates would make the U.S. more competitive with foreign countries for business investment and that companies would reinvest repatriated dollars into capital expenditures, thus growing the U.S. economy. Critics suggested that companies would repurchase shares or pay down debt. Let’s look at where repatriated dollars are going.

Did the companies invest in capital expenditures and acquisitions? There is anecdotal evidence that companies will invest their repatriated cash. On Apple’s Q-1 2018 earnings conference call in February 2018, CFO Luca Maestri stated, “Due to recently enacted legislation in the U.S., we estimate making a corporate tax payment of approximately $38 billion to the U.S. government on our accumulative past foreign earnings.” At 15.5%, this tax payment would cover substantially all of Apple’s $252 billion of trapped cash. In May 2018, Apple followed up and announced the company expects to invest $350 billion in the U.S. over the next five years, including $30 billion in new capital expenditures. Although the company didn’t specify where the funds would come from, it’s reasonable to presume that some will be sourced from repatriated cash.

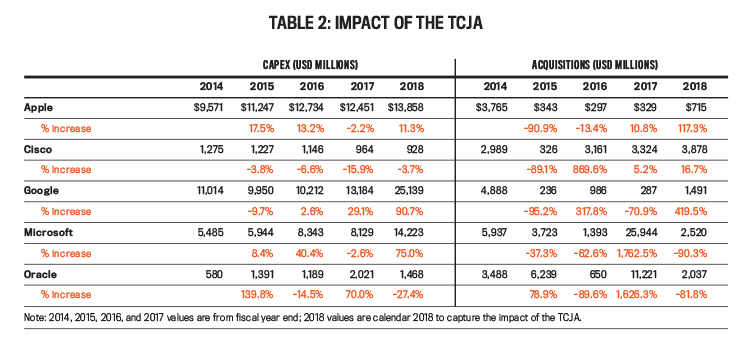

The data doesn’t yet support claims of using repatriated cash for investment in capital expenditures and acquisitions (see Table 2). But it’s far easier in the short term to pay down debt or repurchase shares than it is to identify attractive investment opportunities, so it may be too early to know how repatriated funds will work their way into capital expenditures.

Click to enlarge.

Did the companies use cash to repay debt? While each of the five companies had high levels of cash and cash equivalents, all five also had debt. In 2013, Apple chose to issue the largest U.S. corporate bond offering ever (at the time) even though it had $145 billion in cash and marketable securities, in part because much of the cash and equivalents were held outside the U.S. Apple was able to raise cash through a debt offering at a rate well below the tax on repatriated funds. At the time, the prospectus stated that Apple would use the proceeds for general purposes, including repurchase of common stock and payment of dividends.

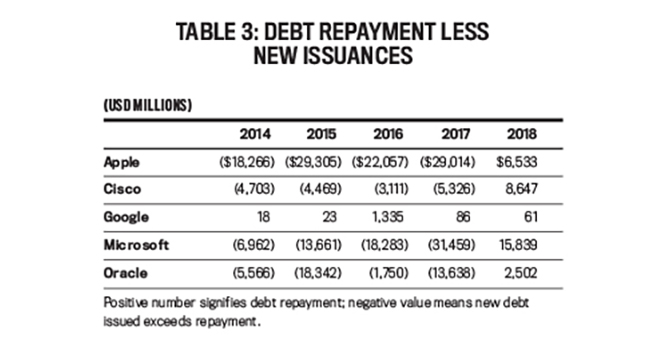

When the tax code gave companies the incentive to keep cash overseas, the companies did just that, and if they needed cash they would issue debt because the interest rate on debt is substantially less than the tax rate on repatriated funds. Table 3 shows the amount of debt repayment less issuances for the companies over the last five years. Note that a positive number means more debt was repaid than issued, and a negative number means new debt issued exceeds repayment. Apple, Cisco, Microsoft, and Oracle had all been adding substantial debt prior to the TCJA. Post-TCJA, they went from adding debt in prior years to paying down debt in 2018.

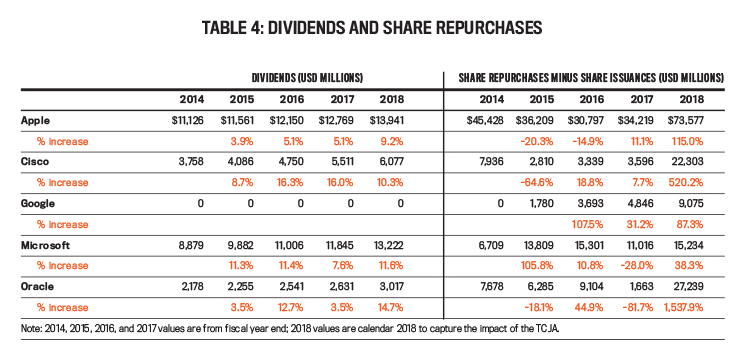

Did the companies increase dividends and/or share repurchases? Early evidence suggests that dividends continued their upward trend and share repurchases increased at most of the companies—a doubling of repurchases at Apple and even more dramatic increases at Cisco and Oracle (see Table 4).

Click to enlarge.

Moreover, both Apple and Cisco have announced significant increases in both areas. As part of Apple’s 2018 Q-2 earnings press release in May 2018, the company also revealed that its board of directors had approved a new $100 billion stock repurchase plan and a 16% increase in dividend payouts or an increase of approximately $2 billion. On Cisco’s 2018 Q-3 earnings conference call May 16, 2018, CFO Kelly Kramer indicated the company had repatriated $67 billion (substantially all of the company’s overseas cash) and paid $11.1 billion in taxes related to the TCJA—roughly 15.5%. Cisco didn’t disclose how the repatriated funds would be used, but the earnings call revealed the board of directors approved a $25 billion increase to its share repurchase plan. There also was a 14% increase in quarterly dividend payouts. It’s worth noting that, to date, Microsoft, Oracle, and Google haven’t revealed their plans for repatriating cash.

WHAT TO EXPECT GOING FORWARD

Since only $600 billion of the estimated $1 trillion dollars in foreign cash has been repatriated and many of the largest U.S. holders of this cash haven’t revealed their plans, the future of trapped cash is far from certain. As we stated previously, it’s too early to assess the impact on capital expenditures, if any, and acquisitions generally have a long time horizon. This means we’ll have to wait and see if statements about investment in the U.S. economy are realized. Based on limited company announcements and our analysis of the five high-tech companies, we know that share buybacks, debt repayment, and increased dividend payouts are on the rise, presumably to the delight of shareholders.

TCJA PROVISIONS ON FOREIGN EARNINGS

The U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was passed at the end of 2017 and became effective for 2018. In addition to reducing corporate tax rates from 35% to 21%, the tax treatment of foreign earnings was changed radically. These provisions attempt to remedy the competitive disadvantages U.S.-based companies faced related to income taxes.

Under the TCJA, the U.S. moves from taxing worldwide income to a territorial tax. Prior to the Act, the U.S. had a system that required U.S. companies to pay taxes on all income whether it was earned inside or outside the U.S. Income earned outside the U.S. was taxed at the local rate (often quite lower than the rate in the U.S.), and the difference was due when the foreign earnings were distributed to the U.S. parent or repatriated. This created an incentive for companies to defer taxes indefinitely by leaving foreign earnings outside the U.S. Under the TCJA, only income earned within the U.S. is subject to the 21% corporate income tax rate (subject to a minimum tax explained below).

As part of the transition to the territorial system, the TCJA requires companies to pay a onetime tax called “deemed repatriation” assessed at 15.5% on liquid assets and 8% on noncash assets. The tax is assessed and included in the 2017 U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) statements. It is due regardless of whether the earnings are actually repatriated and may be paid in installments over eight years.

In addition, the TCJA includes a new global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) provision. Essentially, this is a global minimum tax aimed at reducing the incentive for companies to locate revenues and earnings in low-tax jurisdictions.

INSIDE THE TCJA

Coauthor James Aselta talks with Jeffrey Michalak, EY’s global director of International Tax Services, about activity from the TCJA so far.

James Aselta: How much activity around repatriation of cash in the 12 months (2018) subsequent to the TCJA have you seen?

Jeffrey Michalak: There has been a significant increase in repatriation post-TCJA, no question about it. However, after the first flush of repatriations, I am not seeing big ongoing pressure to fund U.S. needs through repatriation.

Aselta: Do you have a perspective on what the repatriated cash is being used for?

Michalak: No hard figures, but anecdotally it appears much of it is being used for share buybacks, dividends, bonuses, etc. Some companies were borrowing to pay dividends in the U.S., and the repatriated cash was being used to pay down this type of debt. Moreover, for companies that had cash deficits in the U.S., the onetime repatriation was a lifesaver.

Aselta: Did the TCJA remove all obstacles from repatriating cash for U.S. companies?

Michalak: The TCJA removed a major obstacle to the repatriation of cash, but the idea that all frictions on potential repatriation of foreign cash were removed is not completely accurate. Local jurisdiction frictions still remain. Examples include holding company tax, FX [foreign exchange] gains on earnings, withholding taxes, applicability of the dividends received deduction, etc. In addition, in some instances, amended international tax treaties are making access to foreign cash more difficult.

Aselta: I appreciate each company’s tax circumstances are specific to them, but is there any general advice that you would give to companies interested in repatriating cash at this time?

Michalak: The TCJA has created opportunities for companies, but international tax complexities have increased significantly. In some instances, amended international tax treaties are making access to foreign cash more difficult. Before making a decision on repatriation of cash, companies need to consider all the potential tax ramifications, taking into consideration local (including U.S.) jurisdiction tax frictions and consequences.

April 2019