Facing business setbacks, companies altered product data, hid losses, and even resorted to issuing misleading financial reports. Shareholder value was damaged, and consumers were outraged. What changed, and how could these scandals have been avoided?

ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT

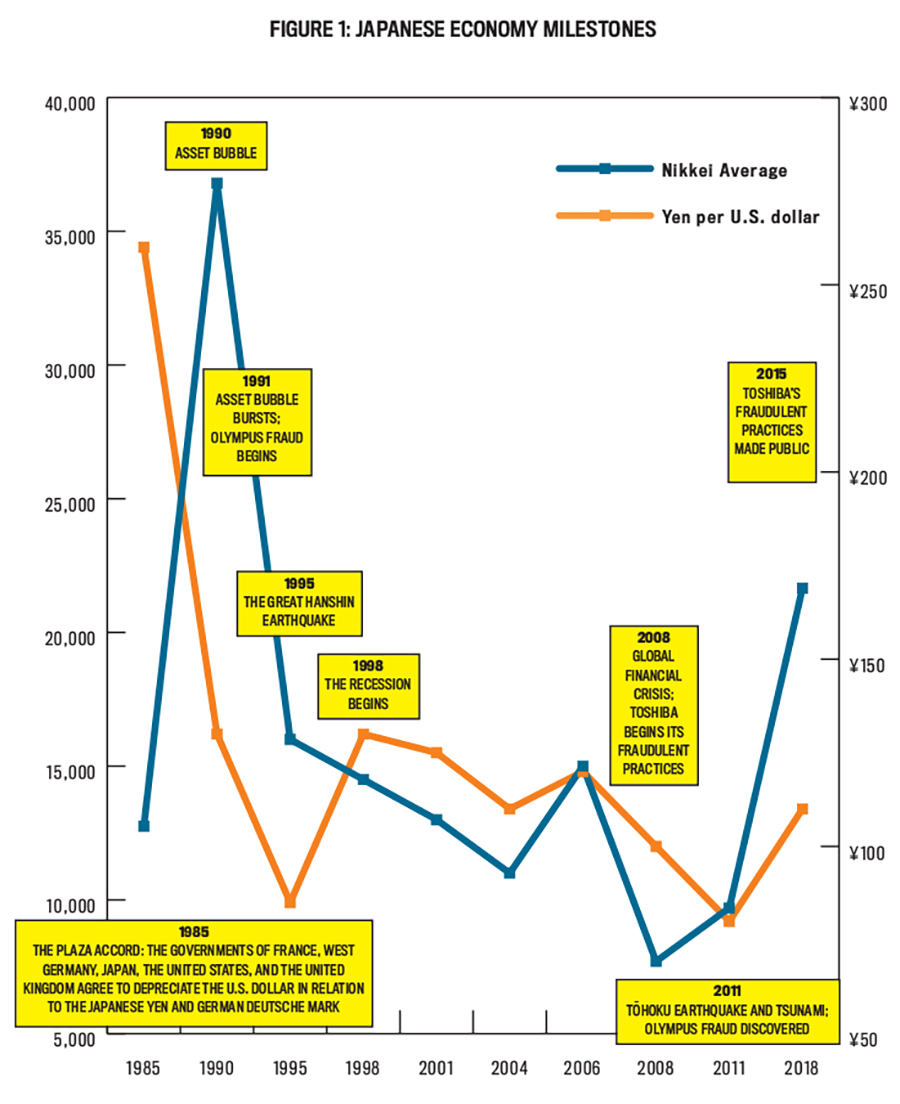

The problems for Japan’s large corporations began with macroeconomic events accentuated by natural disasters that adversely affected Japan’s economy (see Figure 1). Back in the mid-1980s, Japan was the world’s second largest economy, having grown dramatically since World War II. Yet Japanese companies were facing unprecedented challenges. With the rising value of the yen (¥), Japanese goods were no longer price-competitive in foreign markets, resulting in a decline in exports and a slumping Japanese economy. The Japanese government responded with aggressive stimulus efforts that boosted the economy, leading to record-high asset prices, but this was followed by a subsequent bursting of the asset price “bubble” in 1990.

Japan also felt the effect of the 2007 U.S. banking crisis and the global economic downturn. During 2008 and 2009, the country experienced its deepest recession since World War II. A government stimulus package and a rebound in global demand led to a mild recovery by mid-2010. But then in 2011 a 9.1 magnitude earthquake triggered a tsunami that caused major devastation, leading to another recession in mid-2012.

JAPANESE CORPORATE CULTURE

Japanese society has several defining characteristics that greatly influence Japanese corporate culture and helped create the conditions that enabled fraud and ethical scandals. One such characteristic is Japan’s borderline hierarchical society where individuals are conscious of their hierarchical position in any social setting and act accordingly. This is reflected in the corporate world, where there’s a strong need for managers’ decisions to be confirmed by their superiors and by top management.

Japanese culture also exhibits many of the characteristics of a collectivistic society, such as putting harmony of the group above the expression of individual opinions as well as having a strong sense of shame for losing face. Uncertainty avoidance is another defining attribute. According to Hofstede Insights, “You could say that in Japan anything you do is prescribed for maximum predictability” (http://bit.ly/2PmpQwz). Japanese society also has a strong long-term orientation, with individuals tending to view their lives as a very short moment in the long history of humankind.

These various characteristics result in a corporate culture where there is unquestioned obedience and loyalty to the company. Many employees work for the same corporation for their entire careers, with or without advancement. This lifetime employment coupled with little or no job rotation also means that many employees work in the same division their entire careers with the same colleagues. The resulting sense of camaraderie makes it difficult for an employee to correct or question an inappropriate accounting treatment authorized by a colleague. Such a setting compromises the internal system of accounting checks and balances.

Even in the face of unforeseen setbacks in the Japanese economy, many CEOs of major Japanese corporations were sometimes unyielding in their push to meet income targets. And compensation of senior managers was sometimes based significantly on bonuses, which were highly dependent on meeting or exceeding targets. Some CEOs set “challenge numbers” for their subordinates and heads of divisions to meet—even threatening in some cases that the division would be sold or closed if the targets weren’t met. While the CEOs didn’t necessarily instruct their subordinates to commit fraud, they created an environment conducive to fraud and relied on the Japanese culture of obedience and loyalty that led employees to do whatever was necessary to meet these targets, including fraud.

FRAUD AT OLYMPUS

All of these factors can combine to create situations where fraud is more likely to occur. One example of this is the fraud at Olympus, which came to light in 2011. Perpetrated over a number of years by the company’s chairman of the board and past president in collusion with other board members and senior officers, the fraud shocked all of Japan and made headlines worldwide.

Because it relied heavily on exports, Olympus was one of the companies facing pressure from the rising value of the yen in the mid-1980s. Declining export sales led to a decline in the company’s income. Olympus management decided to make up the earnings shortfall by engaging in speculative investments, which appeared promising given the surge in Japanese asset prices. When the asset bubble burst in the 1990s, however, Olympus incurred significant losses on its investment portfolio. Rather than liquidate its investment portfolio and report the losses, Olympus reported the investments at cost while doubling down and investing in even riskier financial instruments. This high-risk strategy failed spectacularly, and by 1995 the amount of unrealized losses had grown to tens of billions of yen.

Despite numerous turnovers in the CEO position due to retirements, all of the incoming CEOs continued to resist disclosing the unrealized losses, although the decision that led to those losses wasn’t theirs but that of a predecessor.

Initially, the failure to disclose these losses wasn’t in violation of Japanese Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), which allowed investments to be valued at either historical cost or the lower of cost or market at the company’s discretion. But a new standard was issued in 1997 that no longer allowed historical cost accounting for investments. Instead, it harmonized Japanese accounting with U.S. GAAP by classifying investment securities into three categories and requiring mark-to-market accounting. The standard became effective on or after April 1, 2000. Olympus would be required to apply the new standards for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2001.

Regardless of how Olympus implemented the new standard, the unrealized losses on its investment portfolio would be apparent to investors. But this option was unacceptable to management. Instead, it embarked on an elaborate “loss separation scheme.” By 1998, unrealized losses on Olympus’s investment portfolio had ballooned to more than ¥100 billion. Unable to offload these investments and unwilling to recognize the losses, senior executives devised an elaborate scheme of setting up shell companies, or tobashi, that would buy Olympus’s toxic investments.

Funds required to purchase the securities from Olympus were diverted to these shell companies through a chain of intermediaries based in the Cayman Islands and British Virgin Islands and also through loans from legitimate financial institutions for which Olympus served as a guarantor and deposited large sums of money as collateral. At the end of the sequence of transactions, Olympus had effectively swapped toxic investments for high-grade Japanese government bonds, held as collateral at the banks, and recorded no loss. Olympus was able to do so because it didn’t have to consolidate the tobashi that bought the toxic investments.

A postmortem investigation revealed that several senior officers at Olympus, including the CEO, president, chairman of the board, head of finance, and executive vice president, were all aware of these funds and helped create them. In fact, the then-chairman of the board and the CEO/president signed an agreement with one of the financial institutions to extend the terms of a collateralized account to one of these shell companies in the amount of ¥30 billion.

The scheme unraveled about 10 years later when the shell companies had to repay the loans to the financial institutions. Unfortunately for Olympus, the toxic assets didn’t recoup their losses in the interim, and the shell companies holding those assets couldn’t sell them to raise the necessary cash to settle the outstanding loans. Olympus had to devise a way to transfer excess funds to the shell companies, enabling them to repay the loans. Olympus’s management attempted to do so under the guise of merger and acquisition activities.

It was one such overpayment for advisory services related to the acquisition of the British company Gyrus that caught the attention of Olympus’s CEO and president at the time, Michael Woodford, and alerted him to a potential fraud. In a scathing letter, he outlined his concerns to the chairman of the board and executive vice president. Three days later he was unceremoniously fired by the board of directors, only six months after having been promoted to the position of CEO and president of Olympus.

FRAUD AT TOSHIBA

Another substantial fraud case that shocked the country occurred at Toshiba. Beginning in 2008 and spanning seven years, the fraud inflated Toshiba’s cumulative net income by ¥150 billion. It primarily involved transactions using the percentage-of-completion method and an unusual transaction known as price masking. Though orchestrated by many mid-level managers, senior management members were cognizant of the transactions and implicitly approved them.

Toshiba was among a handful of companies worldwide that had the technical expertise to build and install nuclear power plants. It secured multiyear, multibillion-dollar contracts to build power plants all over the world. Revenue from these long-term contracts was recognized using the percentage-of-completion method. A key requirement for using this method is the ability to reliably estimate future costs and to disclose anticipated losses whenever estimated total costs exceed the contract revenue. Hence, companies undertaking long-term contracts need to ensure proper policies and procedures that require periodic and objective assessments of these estimates.

There was a systemic failure to timely report contract losses at Toshiba affecting more than 15 of these contracts ranging from ¥500 million to ¥858 billion. In some cases, the contract losses were evident at the inception of the contract. In January 2012 (FY 2011), for example, Toshiba accepted a government contract at a price of ¥7.1 billion when the internal projection of the costs to fulfill the contract was ¥9 billion. In order to justify the contract, which was deemed “necessary in terms of business strategy,” a “challenge value” (i.e., a hard target for quarterly earnings) for the contract costs was set at ¥7 billion, thereby yielding ¥100 million of profits in the best-case scenario.

The reduction of ¥2 billion in contract costs would be achieved through anticipated cost reductions, but at the time of the bid, the sources of those savings weren’t identified, and no loss was recorded in FY 2011. A provision for contract losses was recorded for the first time in the third quarter of FY 2014. The division delayed recognizing losses on this project because they wouldn’t be acceptable to Toshiba’s CEO, who, according to the 2015 investigative report on the fraud, demanded a “moral certainty of loss or firm loss figure” before approving recognition of losses on these contracts.

Toshiba also managed its earnings in its PC division by exploiting a relatively unfamiliar transaction called price masking. In order to take advantage of lower manufacturing costs in the developing world, many companies in developed countries (including Apple, Motorola, and others) design and engineer the products and then subcontract the manufacturing to a production shop. The former is called the original equipment manufacturer (OEM), and the subcontractor is known as the contract manufacturer.

Usually, the OEM buys raw materials or component parts from a supplier and transfers them to the contract manufacturer, which assembles the product and sends it back to the OEM. The price of the raw materials or components transferred to the contract manufacturer is kept a secret for strategic reasons, and an artificial price is used for the transfer, hence “masking” the OEM’s actual purchase price. The contract manufacturer is indifferent to price masking since it will be reimbursed when the finished goods are returned to the OEM. Toshiba exploited the accounting of this unfamiliar transaction by channel-stuffing raw materials to its contract manufacturers (i.e., sending more materials than were actually needed) in order to boost income.

In the aftermath of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, Toshiba exploited the price-masking transactions to manage its earnings. In August 2008, at a high-level corporate meeting, the CEO demanded an additional profit of ¥5 billion from the PC division. The PC division met this challenge by recording transfers to the contract manufacturers at exorbitantly high masking prices. The transfers were estimated to reach ¥14.3 billion by September 2008 and further increased to an estimated ¥27.3 billion by the end of the first quarter of 2009.

Despite this, the relentless demands on excess and unrealistic profits from the PC division didn’t subside. In 2012, the CEO again strongly demanded an improvement of ¥12 billion in the operating profit of the PC business just three days before the quarter-end. The PC division met this unreasonable challenge by further channel-stuffing raw materials to the contract manufacturers. As a result of these transactions, the balance of “buy-sell” profits at the end of 2011 was estimated to be ¥65.4 billion.

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE FAILURES

So why did these accounting frauds go undetected for such extended periods of time? One answer lies in the numerous corporate governance failures that occurred. In a 2017 paper titled “Is the Structure of the Board of Directors Associated with Accounting Fraud?” (http://bit.ly/2Ouxqon), Masumi Nakashima analyzes the incentives triggering the reported frauds in Japan for the period 2007-2015 and finds that institutional incentives, such as protecting the company as a whole, was the prevalent objective for fraud by a subsidiary, far outnumbering personal incentives such as embezzlement by employees or private gains for senior management. Let’s take a look at some of the compromises of good corporate governance at Japanese corporations that contributed to the frauds.

Internal Controls. Two systemic internal controls weaknesses in Japanese corporations are a lack of job rotation and a lack of segregation of duties. At Olympus, for example, the Treasury Group both executed and approved transactions involving external funding. Additionally, the head of the Finance department was also the head of the Audit Office and the officer in charge of audit.

There also was minimal job rotation at both Olympus and Toshiba, especially in key finance positions. Former CFOs at Toshiba routinely served as the chair of the Audit Committee. The oft-used rationale for the lack of job rotation and segregation of duties was a perception that finance functions require a high level of expertise that takes years to develop and that only a few in the company possessed.

Internal Audit Function. For an internal audit department to be effective, it has to be independent of management and have a direct line of communication to the audit committee. At Olympus, however, there was an extended period where the head of the Finance department also supervised the Internal Audit department. Hence, it’s no surprise that the Internal Audit department didn’t conduct a single audit of the finance function over a period of seven years. This was typical of Japanese internal audit functions, which primarily fulfill a consulting role and focus on achieving operational efficiencies rather than identifying and correcting financial improprieties. Suggestions for improvements or changes are only recommendations, with no requirement that senior management implement the changes recommended.

Board of Directors. Japanese boards of directors largely consist of company insiders who are long-term loyal employees. Boards typically aren’t organized into committees, a hallmark of Western corporate governance. The lack of a compensation committee can affect the independence of board members, as at Toshiba and Olypmus, where the chairman of the board would unilaterally decide on the compensation packages of fellow board members. Hence, even if there was debate on contentious issues, the final resolution would be made by the chairman without opposition. Once approved by the chairman, the board would rubber-stamp all corporate actions.

Audit Committee. Though a rarity in Japanese corporations, both Olympus and Toshiba had functioning audit committees with at least one outside director. Yet, as is typical in the Japanese corporate structure, the inside directors were longtime employees of the company with extensive knowledge and background in finance and accounting. The outside director(s) on the audit committee lacked accounting expertise and thus deferred to the inside directors, some of whom were involved in the ongoing fraud, for expertise and guidance.

External Auditors. Low audit fees and long tenures for auditors create an audit environment in which the auditor relies extensively on management’s assertions and lacks the resources to seek the opinion of outside experts on technical or complex matters (such as cost estimates for building nuclear power plants). Additionally, auditors’ warnings to the board of directors often go unheeded. For example, KPMG AZSA LLC, the auditor at Olympus, requested, to no avail, that the Audit Committee of the board of directors consider the reasonableness of the purchase price on the acquisitions and the advisory fees being paid.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

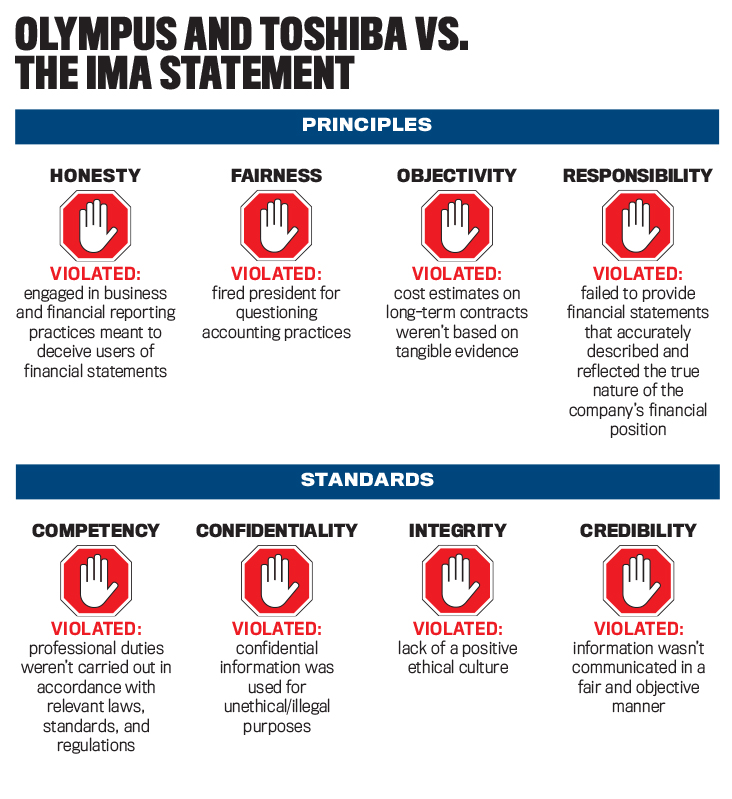

The frauds perpetuated by Olympus and Toshiba employees also resulted from ethical lapses on the part of numerous employees. Theses lapses can be examined through the lens of the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice, which was revised last year to reflect the global scope of management accounting. The IMA Statement requires members of IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) to contribute to a positive ethical culture in their organizations and to place integrity of the profession above personal and corporate interests, thereby fostering a strong, open, and positive ethical culture in their organizations.

The IMA Statement includes four overarching ethical principles—honesty, fairness, objectivity, and responsibility—and outlines standards of competence, confidentiality, integrity, and credibility that IMA members have a responsibility to comply with. “Olympus and Toshiba vs. the IMA Statement” shows how the actions of the employees at Olympus and Toshiba violated the IMA Statement in numerous ways. Had these companies implemented the IMA Statement or similar code of conduct before their financial difficulties began, the outcomes might have been different.

THE PATH FORWARD

The frauds at numerous prominent Japanese companies were, in hindsight, clearly the result of failing to establish proper corporate governance combined with the failure, perhaps understandable given cultural mores, to adhere to ethical standards of financial reporting. Fortunately, progress can be made in both areas.

The government of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has proposed a set of policy imperatives that includes a voluntary corporate governance code. This is expected to be widely adopted as companies will be required to explain why they didn’t adopt or comply with any parts of the code. The code also empowers shareholders and encourages them to voice their opinions when needed.

Additionally, there are frameworks and codes of conduct, such as the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice, that can provide guidance for management accountants when they encounter questionable transactions. By adhering to such a framework and by implementing good corporate governance practices, companies will be able to prosper while avoiding joining the list of “financial scandal” companies.

November 2018