Today’s accounting and finance groups are facing significant change as they move toward digital transformation. Many uncertainties arise along the way, but one reality stands out: Regardless of the excitement around a new technological advance, it won’t be fully successful unless it engages and motivates your people.

Accountants possess vast skills that form a vital strategic resource for any organization. Used at its best, technology can unleash those skills by removing the old barriers of manual grunt work and freeing up time to do other—and better—things. To this end, it’s important for companies to provide opportunities for their people to thrive and contribute. To help our own customers and improve how we serve them at BlackLine, we decided to find out more about the people who employ, deploy, or otherwise engage with accounting technology.

With upwards of 180,000 users, we couldn’t sit at the elbow of each one, so we used internal research to create models of what we consider important accountant behaviors. Here’s what we learned:

- Titles are meaningless. While important for salary, training, promotion, and other reasons, job titles say little or nothing about how a person might function when dealing with change.

- Caricatures aren’t people. No matter how well we may think we’ve modeled a certain behavior, people won’t always act the way we expect.

- Change is capricious. As every manager knows, change can take place in a variety of ways. It can be from the ground up and organic. It can be handed down from above. It can come with a merger or acquisition. It can evolve over time or come bursting in the door at any moment.

In the same way that behavioral models aren’t real people, we need to bear in mind that there’s a big difference between theoretical change and change in the real world. All of that said, we found some consistencies in behavioral characteristics and how they relate to change in the work environment.

We can tell with some degree of accuracy how these model types—what we call personas—will likely relate to the different elements of progress as change occurs, gains greater acceptance, and is deployed in the organization.

THREE QUESTIONS

To construct our models, we evaluated hypothetical responses to three questions that we believe are fundamentally related to dealing with organizational change. Based on the responses to these questions, we then combined the behaviors to create specific types of personalities, or personas.

We grouped the personas via “real-world” personality types: visionary, bellwether, model accountant, and so on. Finally, we determined where in the change process each persona would be optimally placed and what value he or she would bring to the project team. We started with these three questions:

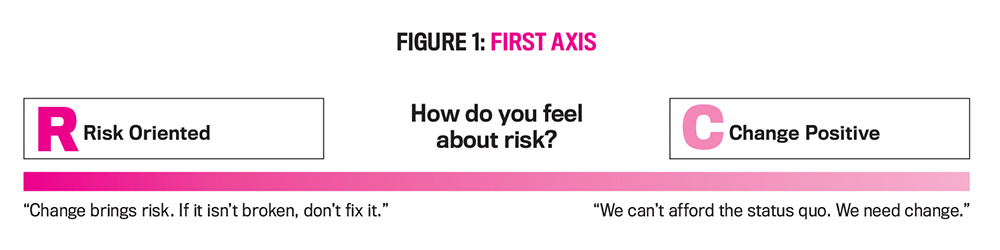

- How do you feel about risk?

The scale for this first axis measures an accountant’s “comfort level” with taking risks. (See Figure 1.) At one end of the scale, the person might agree with the statement, “Change brings risk. If it isn’t broken, don’t fix it.” At the other end, the person would be more likely to agree with the statement, “We can’t afford the status quo. We need change.”

We consider the first persona to be risk-averse, so avoiding risk is a top priority. The second persona is what we call change-positive. Either response is fine—there’s no wrong answer. It takes people of different mind-sets to work with change. But these responses can be helpful in determining where that person might be along the change-evolution curve.

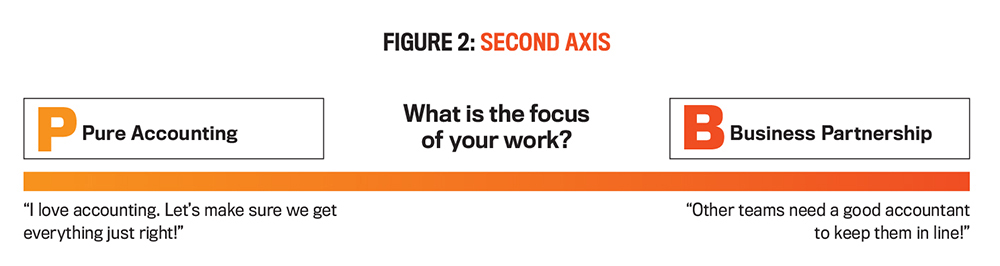

- What is the focus of your work?

The second axis tells us more about that person—specifically whether he or she is more accounting-focused or business-focused. (See Figure 2.) One end of the scale is the statement: “I love accounting. Let’s make sure we get everything just right.” This is what we consider a pure-accounting individual.

The second statement reveals a more business-oriented accountant: “Other teams need a good accountant to keep them in line.” The pure accountant is more likely to focus on the “what?” of accounting: What is happening? What should be happening? The business-oriented person is more focused on partnership with the business side of the organization. That accountant is more likely to want to know the “why” of a task or function, as in: Why did this happen? Why are they doing it that way? Again, there’s no right or wrong answer. What we’re looking for are the differences between people who have these two personality types.

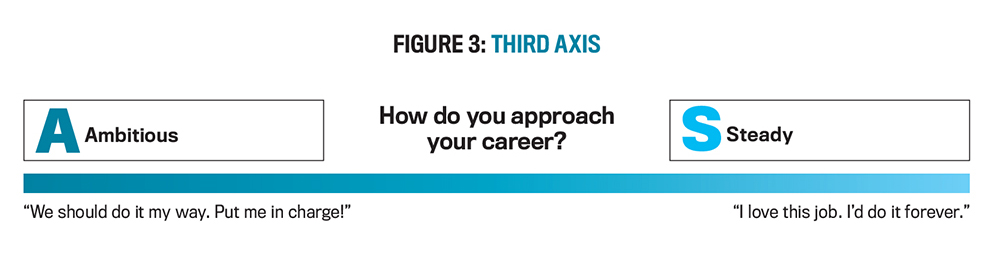

- How do you approach your career?

The third axis, which ranges from ambitious to steady, looks at how each persona approaches a career in general. It’s intended to gauge the level of impact an accountant may have on the organization. (See Figure 3.)

The first statement depicts an ambitious personality: “We should do it my way. Put me in charge.” This is an accountant who might be expected to “make waves” due to a high sense of personal motivation. This also depicts a person who might be somewhat volatile and could pose greater risks and rewards to an organization that’s undergoing change.

The second statement reveals the type of person who will be very good at the job: “I love this job. I’d do it forever.” This person can be expected to be dedicated and meticulous. These qualities are essential to working, sometimes under pressure, with the organization’s lifeblood—the numbers that make up profit and loss.

COMBINING AXES

Each of these attributes gives us a one-dimensional view into our accountants. They’re useful as they stand, but they become more valuable when they’re combined into the multidimensional personas that will be called on to facilitate change.

To start, we separated all personas along the pure accountant/business partner axis. There are compelling reasons for making this division. Today more than ever before, organizational change, even in accounting and finance, will affect other business units. To maximize efficiency, accuracy, and effectiveness, accounting automation solutions often work across multiple enterprise resource planning systems and other nonaccounting landscapes.

Likewise, business and operations departments are increasingly looking to accounting and finance for help with everything from marketing to strategic planning. And accountants are often asked to work with other units. Again, the pure accountant/business partner axis doesn’t suggest that either one is better than the other. Both are valuable and necessary in a well-functioning finance group.

This axis is intended to discover exactly what kind of work a person wants to do. What the axis suggests is how to best motivate various individuals. That can help determine where in the group, relative to changing conditions, each individual might ideally be placed.

Once the accountant and business personas are fully delineated, we add the other possible attributes to fill out the characteristics of the pure accountant and business partner categories to create six personas. A real-world mixture of these six personas on a team would play key roles as organizational change takes place. The color-coding in Figure 4 shows how the original character traits blend into each persona.

Visionary and Bellwether

The visionary and the bellwether are true leaders, with the visionary on the business side and the bellwether on the accounting side. Less risk-averse and more ambitious than their counterparts, they’re important change agents and can have a positive impact on any team they join.

Think of a visionary as a person who readily sees and understands the “big picture.” The visionary can be a major influence at the start of the change cycle since this person believes in the promise of technology to bring about change and can communicate that vision to others. The visionary’s accounting-side counterpart is the bellwether, typically a well-respected change agent with deep accounting expertise. The bellwether can validate and evangelize new ideas because that person understands technology and is both precise and demanding. The bellwether has an unquenchable thirst for knowledge and is the type of person who makes endless requests during a demo to know more about how the product works.Visionaries and bellwethers can come from any level in the organization’s hierarchy, which is why titles and organization charts are irrelevant in determining who the team leaders might be.

Architect and Model Accountant

If the visionary and the bellwether are agents for change, the architect and the model accountant serve as engines for change. Like the visionary and the bellwether, they aren’t risk-averse, but, unlike those two, they are considered more steady than ambitious.

Having a business orientation, the architect can serve as a cross-functional planner and the person who can infuse the ideal with practical reality. The architect is seen as a person who executes on projects, is enthusiastic about technological advances, can work autonomously, and has an innate ability to context-switch.

The model accountant brings strong accounting skills and a willingness and ability to handle any accounting role. This person is comfortable with technology, embraces positive change, and can help iron out key details of the project. These people tend to thrive in high-functioning organizations, and that’s a good thing because they should be considered core components of any new-project team.

Perfectionist and Guru

The perfectionist and the guru share an aversion to risk and may not be as excited about change as the others. As a result, they bring balance to their less risk-averse teammates.

The perfectionist has broad business knowledge and tends to be a steady performer. This is the person who may respond to a new idea with an eye roll and will challenge the wisdom of a “big idea” because he or she knows the systems landscape and what can go wrong. Knowledgeable and detail-oriented, the perfectionist is passionate about the business.

The guru is the accountant’s accountant, in a sense. This person adds important historical knowledge to deep accounting expertise, is often skeptical of new technology, and wants any change to be consistent with good accounting practice and common sense.

All change brings inherent risk, and these people want to know how that new technology might break the system. Together they can fill the vital need for quality control in new projects. They have the knowledge to understand how and where the vulnerabilities may lie, and they aren’t afraid to express their opinions.

Bureaucrat and Purist

Both risk-oriented and ambitious, these people are the challengers, the ones who don’t embrace or may not even trust technology and strive to stifle innovation. Their ambition means they want authority, but they’re likely to defend the status quo.

The more business-oriented bureaucrat often focuses on defining new processes and policies, is orderly and organized, and has a keen understanding of risk. This person will defend the status quo and typically oppose change of any kind, including changes in software versions or vendors.

The purist brings similar traits to the accounting side. This is an accomplished accountant who’s driven to perfect the craft and may view technology as unnecessary or untrustworthy. The purist is inward focused but, because of his or her ambition, capable of influencing others.

These people are typically widely respected and loyal to their craft. They’ve spent their careers perfecting their part of the business, and they regard accounting as a true center of excellence.

AN IDEAL-WORLD SCENARIO

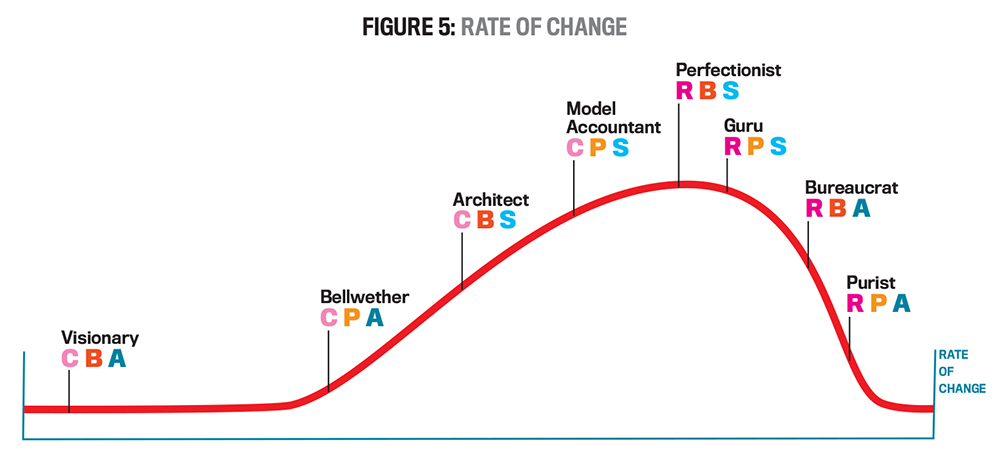

Each of these personas plays an important role on the new-project team for different reasons. While forming the team, it’s best to start by looking at where, along a rate-of-change curve, each will play the most effective role. (See Figure 5.)

In an ideal world, change starts with the visionary—that lone person crying in the wilderness. The visionary has an idea, but the idea doesn’t go far until it finds a bellwether. Once the bellwether gets involved, you have an inflection point. Change starts to kick off, people start to buy in, the idea is getting traction, and others are getting excited about it.

That’s when to get an architect or a model accountant involved. This person starts building out the idea, and, as it takes shape, the rate of change picks up. But it doesn’t peak until you get sign-off from the perfectionist. That’s the person who may be lukewarm to the idea but gives you the okay as long as it doesn’t break anything.

The change is now in effect, and the guru is ready to learn about it and add it to the team’s knowledge. The project is then locked down and any challengers—bureaucrats or purists—are eventually won over.

FORMING A REAL-WORLD TEAM

Of course, putting theory into real-world practice isn’t so simple. The first step is always the hardest and, in this case, one of the most important. Begin by putting together a team that makes the most of the talent around you. These recommendations are based on what we’ve learned through our persona modeling.

Seek out visionaries and bellwethers. Visionaries and bellwethers are often hard to find because they have rare combinations of talent. They’re true leaders and can come from any part of the organization.

One might be buried deep in an organization chart, for instance, reporting up to several levels of managers. Often a visionary has to sell up, so to speak, to get visibility for an idea. The visionary might then have to convince a model accountant or architect that the idea has merit. Some of the most effective projects start with a staff accountant, so you have to watch closely for visionaries who could be staff accountants.

The same goes for the bellwether, who might be anywhere in the reporting chain. You might find a bellwether by watching how others seem to be taking cues from that person. Or, again, they may be someone who’s likely to grill a vendor during a product demo. When you’re forming a team, it’s critical to find your bellwether because that person’s buy-in is necessary to get the project, and other team members, rolling.

Invest in architects and model accountants. These are the people who actually make the process or project work. It’s important to give the architect the skills and knowledge he or she needs to thrive in this position. This person is steady, extremely solid on accounting fundamentals, and at the core of your organization. Look for these people when hiring new employees. Give them abundant training, and encourage them to be as curious as possible.

Find the best roles for gurus and perfectionists. You probably know a guru: the person who seems to know everything. You may also know that gurus can be difficult if they don’t believe in your project. Perfectionists may even use them as brakes for erstwhile projects. It’s important to not respond to the negativity. Instead, find them a role where gurus can contribute positively, do what they love, learn and grow, and help others in their learning. The guru or the perfectionist may be the person on your team you can trust to say, “No, we shouldn’t go with this one.”

Limit or flip challengers. Winning over challengers can be a struggle, but it may be worthwhile in the long run. It can serve as a run-through for what you may face in other parts of the organization as the change takes place. But you do want to limit the number of challengers on your team. On the positive side, you might also find it possible over time to not just win over a naysayer but to actually groom such a person—who has now become a believer—into a leader.

Watch for first followers. This is a person who has the respect of others in the organization and who might suddenly appear, taking up an idea from a bellwether, to further catalyze the change by attracting others to the cause. This person is an outlier to our persona models because he or she can come from anywhere in the organization. The first follower might be difficult to identify at first because his or her leadership capabilities are somewhat hidden.

DOING THE BEST WORK

There’s no simple answer to finding success with change, and there’s no single path along which we can direct our efforts in that regard. Today’s technologies are a blessing to accounting and finance—and to the larger business as well—but they raise many challenges of their own, regardless of the people who develop, deploy, and use them.

What we can do is create the best possible combinations of human skills and characteristics and then let our people do the best work they can.

November 2018