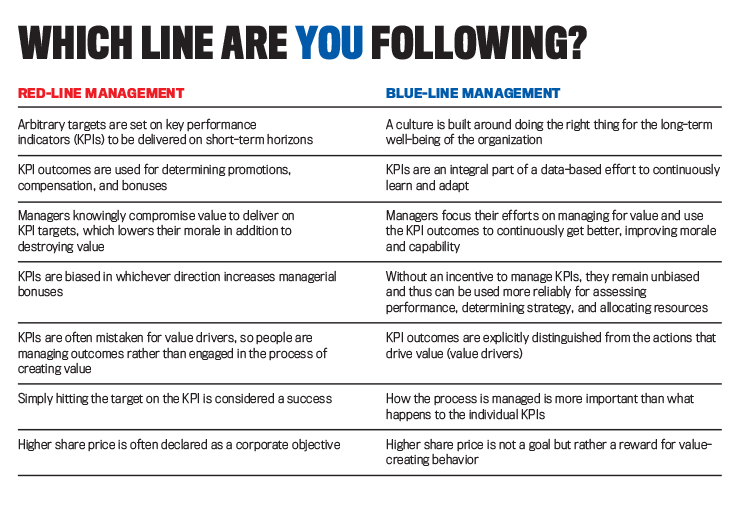

To make these arguments, we propose a concept called “blue-line management,” an approach in which all decisions of consequence are made with one aim in mind: to create value for the organization. This approach stands in stark contrast to the more common practice of “red-line management” in which value creation may be the stated goal, but the business is managed to deliver on specific indicator targets or other objectives to the detriment of value creation.

VALUE CREATION AND THE BLUE LINE

We recently spoke to a group of supervisory board members of publicly traded companies in Europe. We asked the participants to answer a series of questions, with their responses displayed in real time on a screen in front of the room. One of the questions went as follows:

As a (supervisory) board member:

If there is a trade-off between hitting this year’s targets and managing the long-term health of the company (value), which do you want your executives to choose?

- Hit targets

- Long-term health of the company

About 86% of the participants selected “Long-term health of the company,” while the other 14% selected “Hit targets.”

Then we posed a second question:

As a (supervisory) board member:

If there is a trade-off between hitting this year’s targets and managing the long-term health of the company (value), which do you expect your executives to choose?

- Hit targets

- Long-term health of the company

Every participant selected “Hit targets.” None chose “Long-term health of the company.”

How is such a divergence between the responses to these two questions, which differ by only a single word, possible? When asked for their views, the board members revealed that they fully expected their executives to do the opposite of what they wanted them to do. They also said that they were aware that this behavior could be traced to their companies’ compensation structures. Moreover, they expressed the concern that delivering on KPI targets isn’t the same as managing the long-term health of the company and that, in fact, it’s often at odds with long-term value creation.

To create value, a company must systematically invest in projects where the expected value of the cash coming in is greater than the cash going out, a difference commonly expressed as net present value (NPV). Projects that are expected to yield cash flows with a present value in excess of the investment enhance value, while all other projects destroy it. These values depend entirely on the cash flows expected from the investment in a probabilistic sense and not from those based on managers’ forecasts. To put it another way, all investments have an intrinsic value that exists independently of management’s beliefs.

This tendency to confuse intrinsic value with personal estimates of value leads to the serious error of equating price and value. Price is the outcome of a market mechanism, or negotiation, between two or more parties. For any item, from consumer goods to shares of stock, the buyer in a voluntary exchange assigns a value at least as high as the price paid, and the seller assigns it a value no greater than the price paid. There’s absolutely no reason to assume that the price negotiated between these parties is equal to the company’s intrinsic value.

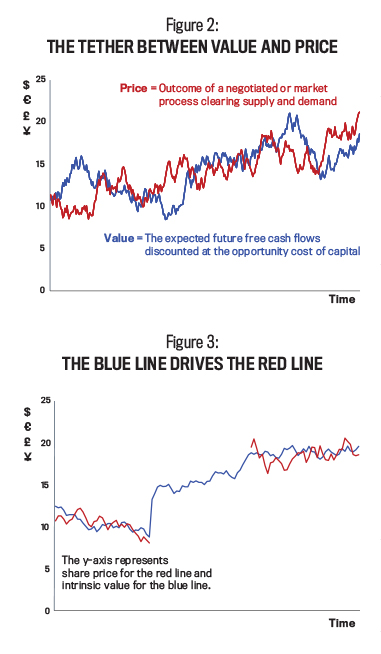

The blue line in Figure 1 illustrates how a company’s intrinsic value might fluctuate over time. Whenever expected cash flows or the cost of capital change, value changes, too. For example, the blue line goes up every time the company invests in a positive NPV project. Seen in this light, the overarching goal of a value-driven enterprise can be expressed as follows: Raise the blue line as high as possible.

The problem with this concept is that the blue line is unobservable. To know the intrinsic value of a company or a capital investment, we must accurately and instantaneously process all information about it—and know everything that might prevail in the future and the precise probability of each potential event actually occurring, as well as the cash flow consequences associated with these events. Therefore, it’s impossible for mortal human beings to know any asset’s true intrinsic value.

Price, on the other hand, arises from consensus forecasts of expected cash flows. These consensus forecasts—and the probability distributions of future events implied within them—reflect the beliefs of many individuals. Although these forecasts may be reasonable estimates, they can never substitute for the true probability distribution that underlies intrinsic value.

Even though the blue line can’t be observed, it still represents the goal for a value-driven business. Every decision a business undertakes impacts value—and therefore the blue line—in some way. In short, every decision either creates value or destroys it, independently of whether managers understand which is which.

Of course, human nature being what it is, managers tend to focus on what they can observe directly. For this reason, companies everywhere rely extensively on a set of KPIs. It’s widely believed that by focusing on observable and measurable KPIs, the business can incentivize value-creating behavior. As we’ll discuss in more detail, this naïve belief has been responsible for staggering amounts of value destruction.

THE TROUBLE WITH RED-LINE MANAGEMENT

The most visible indicator of “value” for a publicly traded company is share price. Indeed, value creation is sometimes expressed (erroneously) as a rising share price. But remember, share price isn’t value. It’s a market consensus of value that’s often mistaken for the real thing.

To clarify this point, consider the graph in Figure 2. The red line depicts the movement of a stock’s price over time. Although we can’t know this with absolute certainty, we would expect the red line to fluctuate around the blue line, which represents the company’s intrinsic value. As deviations between value and price get larger, savvy investors on the lookout for mispriced securities will do one of two things: If shares appear seriously overpriced, they sell or even short the stock; if the reverse is true, they buy. The practical effect of these actions is to tether share prices to the blue line. How much slack remains (in other words, the extent to which shares can be mispriced) is a function of market efficiency, how widely the shares are held, the number of analysts tracking the company, and so on. The extent of the mispricing, therefore, is likely to be far less for a global giant like Procter & Gamble than for a small biotech firm.

For all companies, we expect that the red line (stock price) and the blue line (intrinsic value) will never be equal, apart from the briefest of moments when they cross. This isn’t to say that stock price isn’t an excellent indicator of value—it is. The problem isn’t with stock price as such but with how executives try to manage it to the detriment of value. Given the tether between the two lines, anything managers do that subtracts from value will not only adversely affect the blue line but the red line, too. In other words, value destruction causes the share price to go down, just as value creation causes it to increase.

TUG OF WAR: PRICE VS. VALUE

Figure 3 illustrates what happens to the red line as the blue line changes: The red line on the right side of the graph continues to snake around the blue, but because the blue line is generally higher (value has been created!), share price increases. So if share price is going to fluctuate around the blue line, isn’t it better that it does so around a higher set of values?

With this framing of price and value, blue-line management is the approach that focuses on value creation as the overarching aim of the company. A blue-line company never tries to “manage” its share price. Instead, it simply allows the capital markets to determine price. Put another way, a higher share price is the reward for good management, not the goal. Contrast this approach with red-line management in which management focuses on performance indicators, such as share price, while ignoring the blue line. The stated goal may be value creation, but the reality is something else.

Evidence of red-line management will show up in a number of ways. Two examples are company buybacks, with the aim of increasing earnings per share (EPS), and the massaging of accounting numbers to reduce earnings volatility. A buyback can be justified on several grounds, but doing it to increase EPS is certainly not one of them. This behavior is motivated by the mistaken belief that share price is based on a fixed multiple of earnings. If true, any action that increases EPS—even if it has no impact on the company’s ability to generate cash—will cause the share price to increase. Of course, the signal conveyed by an increase in EPS may be misinterpreted, but when the implied increase in future cash flows fails to materialize, share price is bound to fall.

Another common practice is to create hidden (or “cookie jar”) reserves of accounting profits through the overprovisioning of expenses and losses, including warranties, bad debts, environmental cleanups, and restructurings, to name but a few. The reserves can then be released in future years to artificially boost earnings in low-profit years. This creates a stream of reported earnings that’s far less volatile than the underlying operations of the business imply. Managers play this game for many reasons, but one of them is the false belief that income smoothing can make their businesses appear less risky, thereby increasing share price. When viewed through the lens of blue line/red line, however, it becomes clear that such games are counterproductive.

THE DANGERS OF INDICATOR-BASED PAY

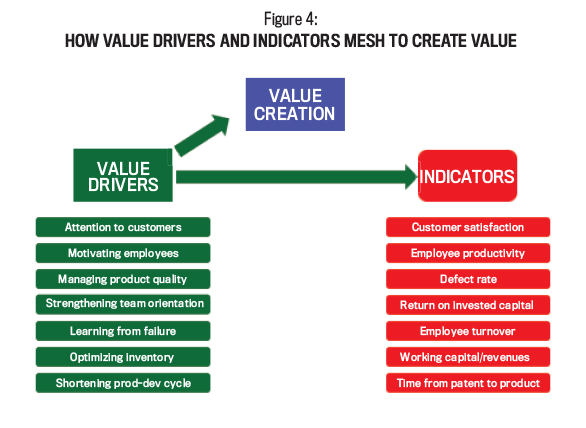

As mentioned earlier, much of red-line behavior at the corporate level is motivated by the desire of senior managers to finesse share price. Similar thinking, however, can occur at any level of an organization, principally through the misuse of KPIs. As shown in Figure 4, value creation is achieved through actions and behaviors commonly known as value drivers. Examples include motivating employees, relationships with customers and suppliers, getting new products to market more quickly than the competition, creating a strong team-based culture, the positioning of equipment and machinery in factories for maximum efficiency, and so on. These behaviors and actions truly drive business success.

But because these value drivers aren’t directly measurable, companies rely on KPIs instead. Indicators are the observable results of behaviors after the influence of myriad random factors that arise between business decisions and their outcomes. Indicators do say something about value drivers, but indicator outcomes also are determined by factors that have little or nothing to do with the actions of management, such as competitors’ strategic responses, changes in the prices of key inputs, and changes in the regulatory and macroeconomic environment. For this reason, an indicator should never be mistaken for a value driver, just as we must never confuse share price with intrinsic value.

Don’t misunderstand us: There’s nothing wrong with indicators per se. In fact, as we will discuss later, any complex organization must be indicator focused; otherwise, there’s no practical way to gauge how well key processes and systems are being run or how they might be improved. The problem arises when indicator outcomes, rather than the underlying value drivers, become the focus of the business. In effect, red-line behavior spreads through all levels of the organization as employees discover that it’s in their best interest to deliver on the indicator targets—even if value is wrecked in the process.

CREATING VALUE ONE STEP AT A TIME

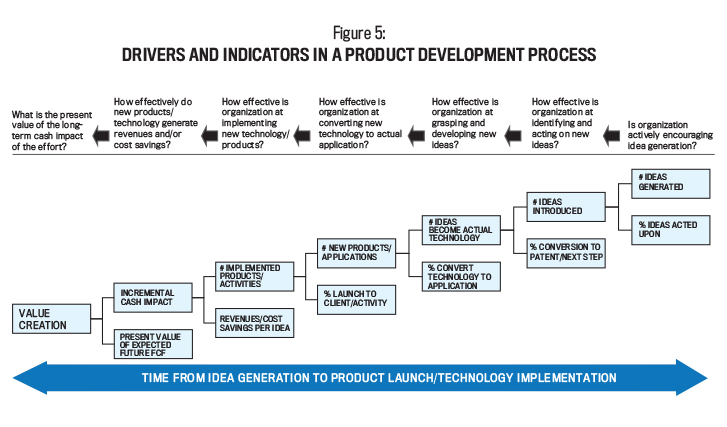

Figure 5 illustrates how a large specialty chemicals company has mapped out its R&D process. For each box, there are behaviors that take place behind the scenes to drive performance and an indicator that summarizes observed performance for a given period. For example, converting technology into applications (enhanced functionality of products, new product features, and process innovation) is deemed to be a value driver. Because of its importance to the long-run success of the business, the managers in charge are measured on how well they did on this dimension. But here’s the problem: As soon as we take a value driver and try to measure it—by putting a euro sign, point value, or percentage sign in front of it—the driver’s very nature has been transformed. At that point it becomes an indicator.

Returning to Figure 5, consider what happens when a manager is held accountable for converting technology into practical applications. A manager who is evaluated and incentivized on the percentage of technologies converted may discourage or reject ideas that are potentially path breaking but that have a high risk of failure. Meanwhile, any project with a high probability of success, even if its contribution to value is marginal or negative, will be accepted. The result? The manager’s behavior leads to a high observed value for the metric, but value is destroyed, or, at the very least, value-creating opportunities are passed up.

An additional concern when metrics are used for incentives is that the metrics no longer will indicate what managers think they’re indicating. Instead, they become contaminated by the conscious efforts of decision makers to manage them. Of course, any indicator can be gamed, but what we’re describing here is something deeper and more troubling. Employees may be managing in good faith to achieve KPI targets—without any conscious effort to deceive—but the result is that already noisy proxies for value drivers become even noisier, and their use in diagnosing genuine problems or knowledge gaps is seriously compromised.

But the negative effects don’t stop there. As everyone in the organization manages to KPIs, it becomes impossible to trust the indicators or to interpret them in a meaningful way. Managers will therefore be unable to understand how changes in behavior impact either outcomes or value creation. Given the inherent difficulty in distinguishing positive NPV projects from negative NPV, even in the best of circumstances value creation becomes a practical impossibility because all numbers are “lies” to varying degrees. When used properly, indicators are instruments to promote learning and continuous improvement. But they work only if no one is manipulating or interfering with them.

In addition, as employees are incentivized to deliver on specific indicators, and thus begin to manage them, they quickly realize that they and their coworkers no longer have a shared or aligned purpose. Indeed, even when senior managers insist that they’re still focused on value and expect everyone else in the organization to do likewise, middle managers understand that they’re being paid to deliver on indicators independent of value creation. As a result, in the face of a compensation scheme that pays for value destruction, any claim by senior management that employees should be focused on value will simply reveal management to be either dishonest (they aren’t speaking truthfully) or confused (they don’t understand the difference between creating value and delivering on an indicator). In either case, employees will lose sight of their common purpose and will stop working toward the same objective.

A BLUE-LINE APPROACH TO KPIS

If indicators should be neither carrots (to reward employees who hit targets) nor sticks (to punish employees who fail to deliver), what’s their proper role in a value-driven company? We believe the primary function of KPIs in a value-driven business is to promote organizational learning, a mission that will almost certainly be undermined when indicators are used for incentives.

Consider a scientist conducting an experiment. For the experiment to advance the store of human knowledge, the scientist can’t have a stake in the outcome one way or the other. We all know of the controversy that always arises from industry-sponsored studies on product safety. It isn’t that the studies are flawed (although they might be) but that the sponsors have a large economic stake in the outcome. Therefore, for genuine learning to occur, we need unbiased experiments, rigorously constructed and with findings based on relevant and reliable data. Paying business managers based on indicator outcomes is comparable to paying a scientist based on the results of an experiment. In such cases, how can we expect experimentation to be unbiased? And if it’s biased, how do we interpret the results as reflected in the indicators? Where’s the learning?

Technological and scientific progress has given us products and services that perform in ways that were unthinkable a generation ago. But these advances have come at a price: ever-increasing complexity. Products may be more reliable, functional, and durable than ever, but the business systems needed to deliver them have become very complicated. A logical consequence of this complexity is ignorance and uncertainty because many systems are too complicated for managers to know all that they need to know to maximize value creation. Although companies may go to great lengths to design and document systems and processes, something important will always be overlooked. Therefore, it becomes impossible to predict how a system will perform under the full range of circumstances that may occur in the future. In short, there will always be knowledge gaps.

Value creation is ultimately about how we manage this ignorance. In an uncertain, complex world, the successful business culture is one in which everyone is continuously learning. It’s also a culture in which having the right answers is less important than asking the right questions. In other words, value creation demands experimentation. In a value-based culture, not only is trial and error tolerated, it’s strongly encouraged. Only through continuous trial and exploration—and, yes, failure—will we gather new, relevant information to help us better understand the business and how to get more value from it. Such a culture can’t possibly prevail if managers are forced to obsess about outcomes.

Indicator targets are important but not because we need them to motivate performance. When set honestly, without the game playing that’s so common in budgeting these days, targets are hypotheses about how business systems are supposed to work. They reflect expectations based on imperfect knowledge. The actual outcomes for KPIs will then reveal the extent to which our understanding of the system was incorrect or incomplete. In effect, indicators act as early warning signals, the proverbial “canary in the mine shaft.” The surprises that inevitably result from the discrepancies between targets and outcomes reveal problems as they emerge, allowing us to plug knowledge gaps and resolve problems faster.

WHAT IT MEANS TO YOU

Great swaths of wealth have been destroyed because of a common tendency among business executives to confuse value and share price. Shareholder value doesn’t come from a higher share price but from positive NPV investments and other actions that raise the company’s blue line. Indeed, one of the great ironies of managing a publicly traded company is that the more attention and resources that are devoted to managing share price, the more the share price falls.

Similarly, delivering on KPI targets is no guarantee of value creation. In the many executive development programs we’ve taught in recent years, we always ask the participants, “Over the past five years, how often have you achieved the targets set for you by your boss?” Invariably, the answer is either “most of the time” or “all of the time.” Then they admit, somewhat sheepishly, that they have often cut corners to make the boss happy. For example, they underinvest in brands or training to trim short-term costs, or they play revenue recognition games to artificially boost sales growth.

When managers are incentivized to manage to the indicators, the indicators no longer represent what they’re supposed to represent. Sales growth and profit margins, for example, are undeniably important indicators, but how can we as management accountants interpret them when we know that, to some extent, they’re lies? KPIs are indispensable to organizational learning, but this critical function can work only if the performance measurement system is designed to reveal the truth.

Parts of this article were adapted with permission from The Blue Line Imperative: What Managing for Value Really Means by Kevin Kaiser and S. David Young, published by Jossey-Bass (a Wiley Brand) in 2013.

June 2018