The competition is named in memory of Carl Menconi, who held leadership positions in IMA for many years and served as chair of the IMA Committee on Ethics. The objective of the competition is to develop and distribute business ethics cases with specific application to management accounting and finance issues and that use the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice as a reference or guidance tool.

The winning case and teaching notes are available for use in a classroom or business setting. IMA academic members can access and download the teaching notes from the Academic Teaching Notes library via the IMA Educational Case Journal section of IMA’s website: www.imanet.org/educators/ima-educational-case-journal.

SHIP BREAKING IS A MULTIMILLION-DOLLAR INDUSTRY. A large percentage of operations are in emerging countries, such as Pakistan, fueled by the high demand for the recycled metals in those countries. Emerging countries have low wages, and both safety regulations and employee protections are minimal or nonexistent. In addition, the hazardous and toxic materials represent a danger to employees long after they finish working in the yards. Regulations are rarely enforced because the recycled metals drive the local economy.

Nonetheless, when Don Welch, a CMA® (Certified Management Accountant), was hired to be the CEO of the Ship-Breaking Company (SBC) in 1985, he didn’t anticipate that in the fourth quarter of 2017 a major industrial accident at the company’s contracted Pakistani ship-breaking operation would kill 19 and seriously injure more than 50 employees.

Welch asked CFO Alicia Gaines to help navigate the company out of this challenging period. Like Welch, Gaines also is a member of IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) and a CMA. Welch put Gaines in charge of investigating the accident and the possible alternatives available to the company. In investigating the Pakistani operation, Gaines was shocked by the systemic safety failures and the continuing dangers to the employees. Welch had to make a decision quickly, and it would determine the fate of the organization and his legacy.

THE COMPANY’S HISTORY

SBC was formed in the United States during the early 1870s to recycle ships decommissioned after the Civil War. It continued dismantling and recycling ships used in military and mercantile operations through the Industrial Revolution. SBC slowly grew to be the top ship-breaking company in the U.S. Eventually, it went public with little fanfare in 1957.

The business operated profitably until the 1980s, when companies in emerging countries cut into its mercantile ship-breaking business. Employees in emerging countries were willing to work for less than $2 per day, compared to $30 per day in the U.S. SBC operations also met strict safety standards required by U.S. law, which made the operation more costly. In addition, the U.S. entered a period of reduced military activity, and the expected revamping of military vessels would occur slowly over the next two decades. The combination of global competition and a reduction in U.S. military activity seriously hurt SBC’s operating profits. SBC slowly began to burn through the cash reserves it had previously built up during its many years of prosperity.

In 1985, faced with mounting operating losses, the board of directors appointed Welch to the position of CEO and chairperson of the board. In the summer of 1988, Welch expanded SBC’s business beyond breaking ships to include recycling of all types of metal and contracted with a ship-breaking operation in Pakistan to compete in the global mercantile ship-breaking business. As part of the turnaround, the company name was changed to the Ship Breaking and Super Recycling Company (SBSRC).

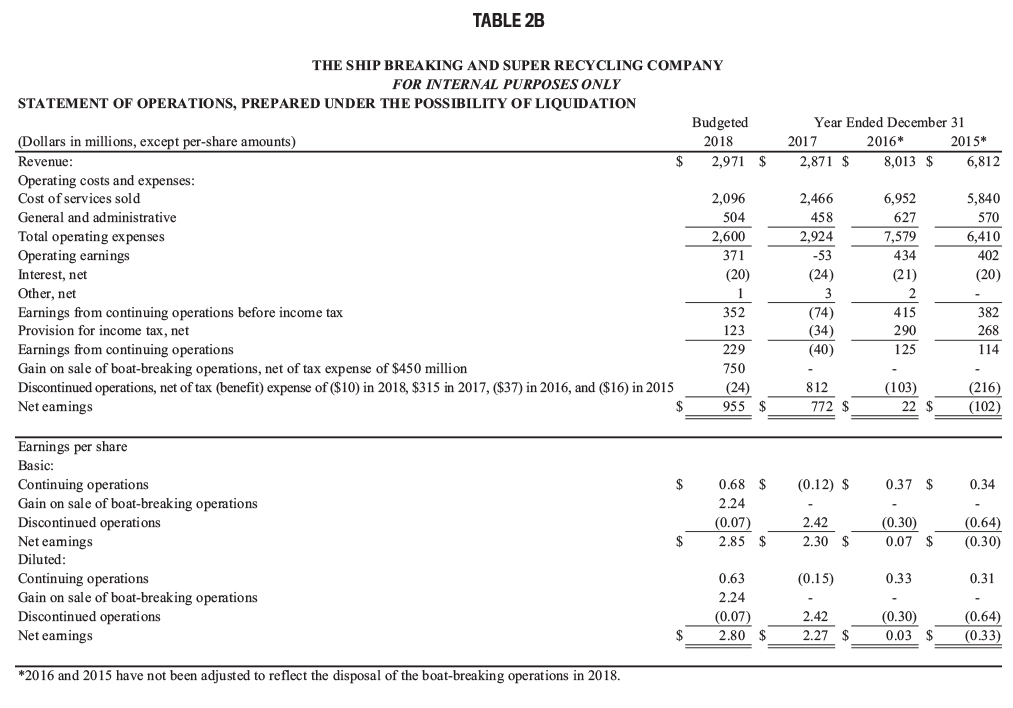

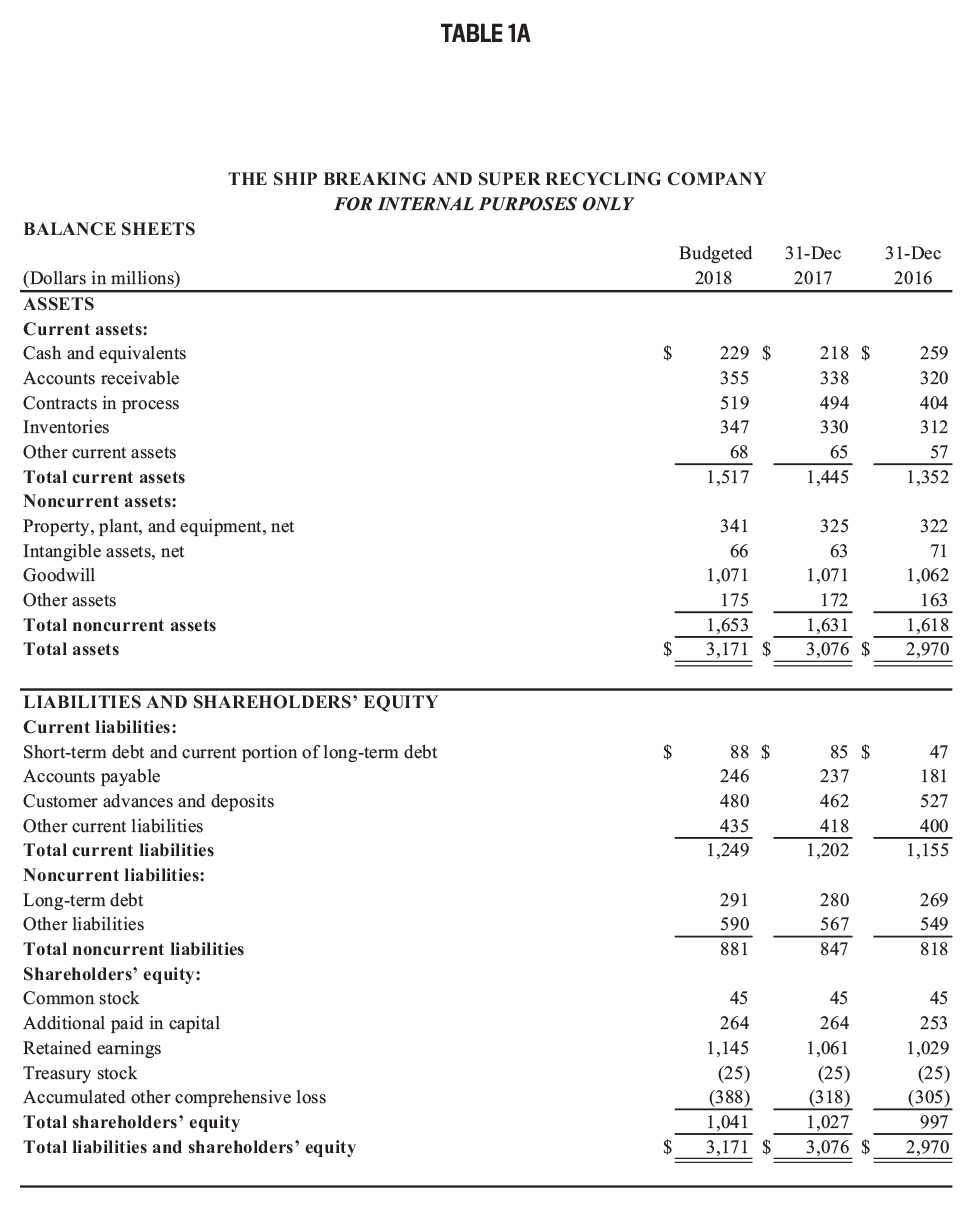

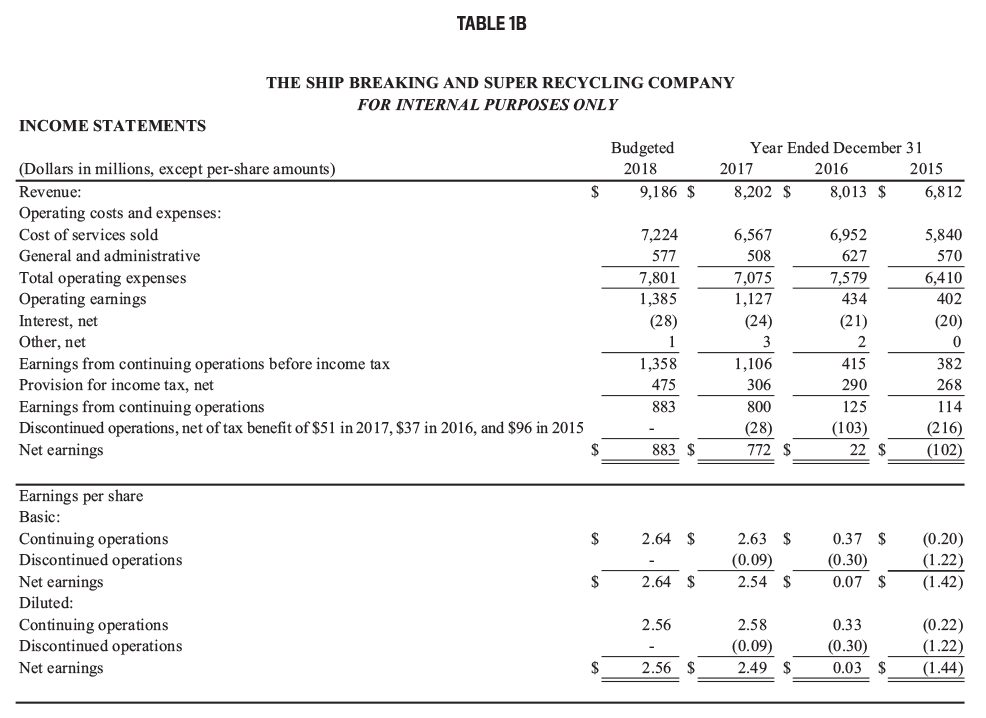

After two decades of success, SBSRC posted net losses from 2013 through 2015, but the ship-breaking operation in Pakistan remained profitable and kept the company afloat. To avoid bankruptcy, Welch decided to discontinue some less-profitable recycling activities, which resulted in a small net profit in 2016. During 2016 and 2017, the ship-breaking operation represented 65% of SBSRC’s revenues and 85% of pretax profits, and the 2018 budget reflected continued operations (see Table 1A and 1B). But the accident threatened that plan.

DON WELCH

Welch is a hard-nosed businessperson with powerful political connections who acts quickly when faced with problems or uncertainty. After his hiring, he quickly initiated a lobbying department that resulted in SBC receiving several new contracts from the U.S. Navy to dismantle and recycle decommissioned warships. Welch turned around the mercantile ship-breaking operation by outsourcing all nonmilitary contracts to a contractor in Pakistan. In another major move, he initiated and then later abandoned a metal recycling business in the U.S.

Welch’s quick and decisive decision making helped SBSRC weather downturns in the military ship-breaking operation and the eventual fall in scrap-metal prices. He and the shareholders were largely pleased with the results throughout his tenure. Welch’s decisions meant that SBSRC was profitable, paid dividends to shareholders, and compensated top executives, including Welch, with large stock bonuses. He relied on the goodwill he earned to weather net losses from 2013 to 2015. Now faced with an unprecedented challenge, he knew he had to act swiftly.

ALICIA GAINES

In early 2016, Welch hired Gaines to help manage SBSRC’s financial business. Welch wanted to focus on the operations, but he knew that after losses from 2013 to 2015, the company would need a skilled professional to manage the company’s cash flows. Gaines brought two decades of experience at a top multinational conglomerate, where she relied on her expertise as a financial professional to become the vice president of Finance for Aerospace Systems.

After some recruiting from Welch and the offer of a significant stock compensation package, Gaines agreed to become CFO of SBSRC. She effectively managed the financial challenges throughout 2016, including the divestment of the recycling business. In doing so, she became someone Welch relied on heavily in his decision-making process.

THE ACCIDENT AND INVESTIGATION

Early in the fourth quarter of 2017, Gaines was reading The Wall Street Journal when she came across an article titled “Explosion at Pakistan Boat-Breaking Yard Kills More Than 10 People.” Gaines recognized this was the same ship-breaking yard SBSRC used. She rushed to see Welch, and the following conversation took place.

Gaines: Don, have you seen the news?

Welch: No, but while I was in a meeting, my phone was ringing off the hook. Jonathan told me I have 20 messages, and three are from board members. What happened?

Gaines: There was an accident in the ship-breaking yard in Pakistan where we have our ships recycled. Preliminary reports say more than 10 are dead and up to a hundred could be injured.

Welch: Izad [Bukhari] assured me years ago that hazardous conditions were “not a risk for his employees.” It’s clear that something changed. We need to get out in front of this. Can you make it a priority to do an investigation and report to me by the end of the week?

Gaines: Yes.

To her dismay, Gaines’s research revealed 19 people died in the accident and more than 50 others were severely injured when a welding torch ignited fuel vapors within a ship’s hull, causing an explosion and fire. Gaines further discovered that safety conditions in ship-breaking operations in emerging countries overall were dismal. Workers died in explosions, were crushed by falling metal, suffocated, fell to their deaths, or were cut in half by snapping cables under great tension. Gaines met with Welch, where she relayed that information and more.

Gaines: There were 19 deaths, and more than 50 others were severely injured. I found that there are systemic and serious safety risks at Izad’s operation; the employees have been lucky to avoid a major accident until now. On average, one employee is killed and 10 employees are seriously injured for every two ships recycled in emerging countries. These deaths and injuries are in addition to any unreported accidents and long-term diseases caused by toxic materials. My figures show we help Izad employ 4,000 workers. These workers face the risk of serious injury or death every day.

Welch: I’m concerned about our employees and their safety; I’m also mindful that each one of those ships nets us about $10 million in profit. I am not sure what to do. Let me contact Izad, legal, and the board. I will get back to you in a few weeks.

Gaines: Don, I think we need to look at this issue from every angle. Throughout my career, it’s been important to me to work through issues objectively. We have a responsibility to SBSRC, but we should disclose this research and a complete picture to the board.

Welch: I agree. My reputation is inextricably tied to this company and the culture and working environment we create for our employees. I dedicated three decades of my life to SBSRC, and I don’t want SBSRC mentioned in the same sentence as Enron.

After the conversation, Welch promised himself, “When I leave SBSRC, other CEOs will be inspired by my leadership. We will follow the laws and do what is right for the shareholders and employees.”

THE AVAILABLE ALTERNATIVES

During the next month, Welch met with SBSRC’s legal team, discussed the issue with Izad Bukhari, owner and president of the Pakistani ship-breaking operation, and met with the board of directors. Together with Gaines, he worked to develop alternatives for SBSRC to navigate the accident. The board agreed to follow Welch’s recommendation among the three alternatives presented to them:

- Do nothing and continue the ship-breaking operations in Pakistan,

- Continue the operation in Pakistan after signing an agreement with Bukhari requiring improved safety conditions, or

- Sell the contracts for the ship-breaking operation to Chinese investors and restructure operations.

Welch sat in his office on a Saturday looking out his window. He lamented that none of the choices was ideal. He felt sick over everything that happened and that all he’d worked for was changing beyond his control. He worried that he wouldn’t be able to live up to the promise he made to himself earlier about doing what’s right for the shareholders and employees.

Do nothing and continue the ship-breaking operation in Pakistan. SBSRC’s legal counsel reviewed the incident, case law, and international law. After their review, they advised Welch that there was little to no risk to SBSRC. The contracts with Bukhari and the legal environment in Pakistan protected SBSRC from legal liability.

They also found that other ship-breaking businesses and contractors that experienced similar accidents were able to avoid long-term negative consequences. In those instances, the negative press faded by the next quarter, and management was no longer answering questions about safety concerns during public appearances. Welch knew that fourth-quarter earnings were shaping up to be good. If SBSRC didn’t have to implement changes, then its after-tax earnings per share would exceed analysts’ expectations by $0.05 per share.

Continue the operation in Pakistan after signing an agreement with Bukhari requiring improved safety conditions. Welch knew ship breaking was dangerous, but he trusted Bukhari to protect his employees. They had been doing business together for decades. Bukhari took over the business about the same time Welch became CEO. But the information in Gaines’s report made him rethink his relationship with Bukhari. He wondered whether he let his friendship interfere in their business relationship. Welch had no idea that conditions in the Pakistani ship-breaking yards were as bad as in other emerging countries.

Given his relationship, Welch felt he should travel to Pakistan to speak with Bukhari personally. After meeting with legal, he boarded a plane for Pakistan and met with Bukhari the next day.

Welch: I wanted to make it out here as quickly as possible. I am sorry that so many employees were injured and killed.

Bukhari: Thank you for coming. I appreciate your kind thoughts and your flying here so quickly. It has been too long, my friend.

Welch: Tomorrow will mark two weeks since the accident took place. How are the injured workers and the families of those that were lost?

Bukhari: It has been difficult, but things are returning to normal. My employees are highly compensated and are good providers for their families.

Welch: What safety measures are you implementing to prevent similar accidents?

Bukhari: My employees are safe, and this accident occurred because those employees were careless. It’s unfortunate, but bad employees will hurt themselves. There isn’t much more I can do. Safety harnesses and hooks may prevent falls, but most of the safety measures in your country make their workers less safe and slow them down. How can one escape fire or falling metal if they’re locked in place? The employees need to be able to move and work quickly. Otherwise, I won’t be able to run a profitable business.

Welch: I understand costs will increase. We’re in tough times, but I want the employees to be safe. I need you to certify that new safety measures are in place and that they’ll continue going forward.

Bukhari: Of course, my friend, new safety measures will be put in place. Have your planning team contact me. Now let us put this unfortunate incident behind us and share a meal and drink.

In the past when Welch discussed safety with him, Bukhari proudly reported that the ship-breaking operation was safe. Bukhari touted, “My business is the safest in all of Pakistan. I am following all applicable safety laws, but I could not afford to compete if I have to implement safety standards like those in the U.S.” Welch felt uneasy about Bukhari’s quick agreement. He knew SBSRC had little leverage over Bukhari. Bukhari’s ship-breaking operation has grown since the 1980s and employs almost 40,000 workers. SBSRC’s business represented less than 10% of Bukhari’s total revenues.

Sell the contracts for the ship-breaking operation to Chinese investors and restructure operations. When Welch returned from the trip to Pakistan, Jonathan (his executive assistant) had an important message waiting from Wendi Pemberton, the longest-tenured nonexecutive member of the board. Welch and Gaines arranged to meet with Pemberton. At the meeting, Pemberton brought news of an offer to purchase SBSRC’s ship-breaking operation for $1.2 billion from a group of investors in China. If accepted, the sale would be effective on January 1, 2018. The sale would exchange $400 million of contracts-in-process and contracts worth $800 million extending five years into the future. The ship-breaking operation would be moved as quickly as possible from Pakistan to China.

Welch felt better about the ship-breaking operation in China. The Chinese companies paid their employees twice as much as Pakistani workers and had better equipment, which would result in much safer conditions for workers. Few Chinese ship-breaking employees were injured or died on the job.

Gaines noticed Welch’s hesitation during the discussion with Pemberton and arranged to meet with him the next morning.

Gaines: This seems like great news, but I’m not sure you see it that way.

Welch: If we sell, we would need to restructure. I did the preliminary calculations, and it would likely mean 6,000 layoffs, which includes all of the Pakistani employees and 2,000 in the U.S.

Gaines: Wouldn’t that put our business at risk?

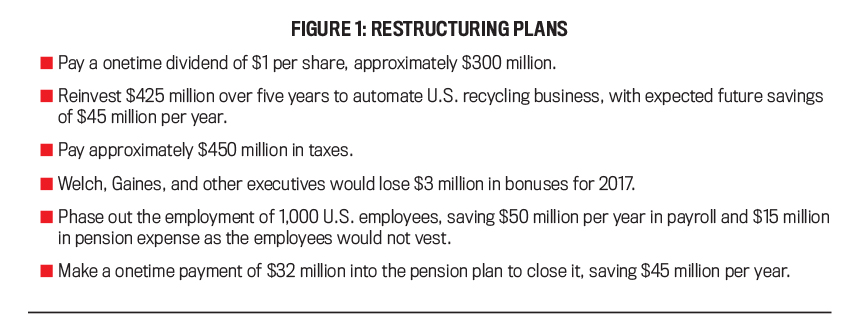

Welch: No, the restructuring plan I’ve been working on since you brought the accident to my attention sets us on a path to profitability. Unfortunately, it would mean SBSRC would exit the ship-breaking industry after 130 years. I’ll get the restructuring plan to you this afternoon. I’ve scheduled two meetings next week with our auditors and the board. (See Figure 1.)

Click to enlarge.

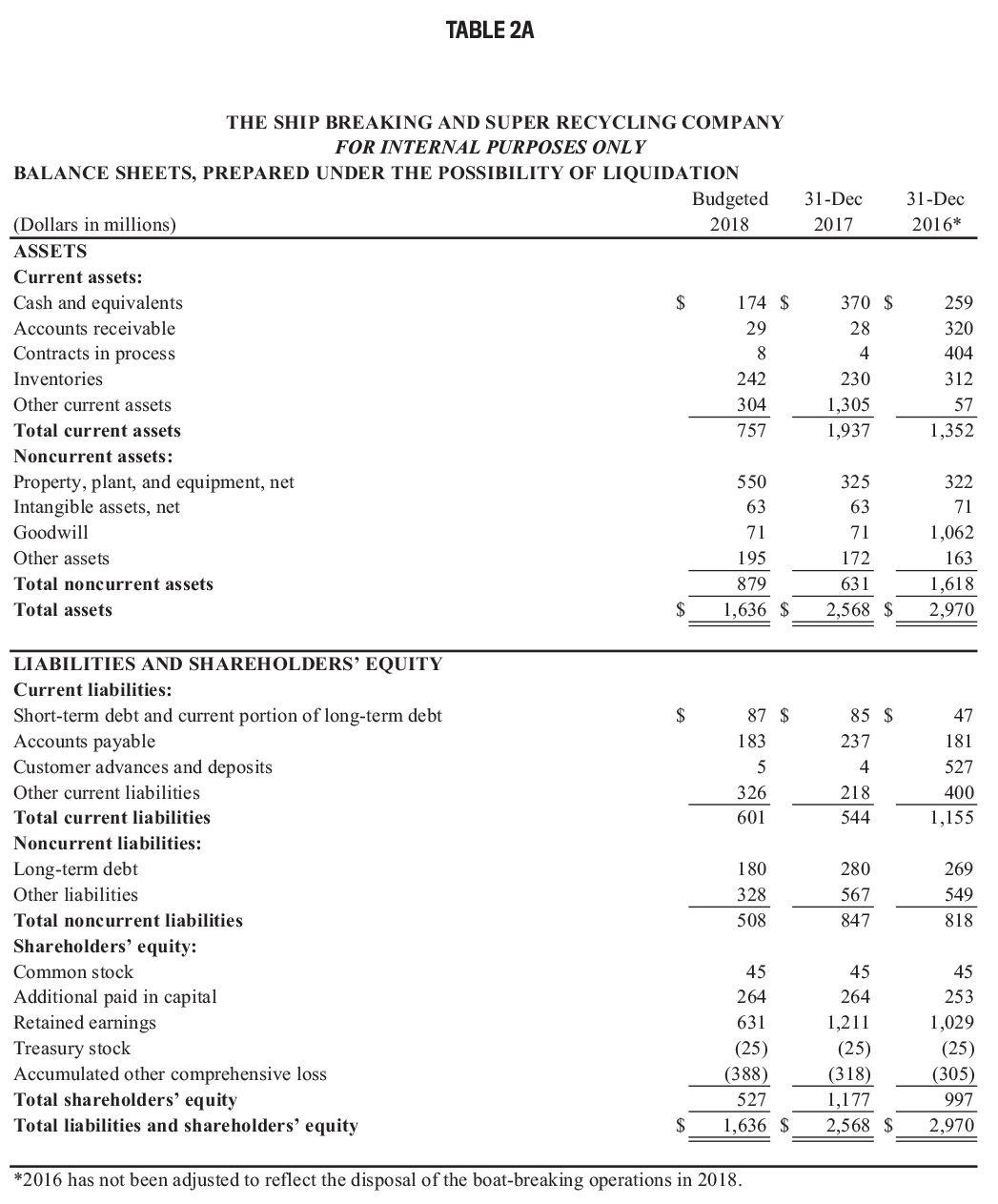

After the meetings, the auditors insisted that the restructuring plan might not create profits going forward, and Gaines created financial statements that reflected their worries that SBSRC wouldn’t remain a going concern. This made the decision more difficult. Welch knew that employees who were working in the ship-breaking operation risked death and serious injury only because the pay is the most they could earn. Jobs for low-skilled workers in that region of Pakistan are difficult to come by, leaving many families without basic necessities. That hardship would be compounded by the layoffs at home. He knows many of the employees stateside personally, and telling them they were no longer part of the SBSRC family would be difficult (see Tables 2A and 2B).

Click to enlarge.

REQUIRED

Write out your answers to the following questions, and support your answers using the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice and the details within the case study.

- Identify the ethical dilemmas presented in the case.

- Review the IMA Statement, and discuss the standard(s) most applicable for Welch to consider in selecting a course of action.

- What are Welch’s responsibilities as the CEO and chairperson of the board of SBSRC?

- Discuss whether there is (are) conflict(s) between Welch’s responsibilities to SBSRC identified in question 3 and Welch’s committing to the IMA Statement.

- Critically evaluate the alternatives available to Welch, and discuss which alternative you would select if you were Welch.

- Develop and present an alternative not discussed in the case.

July 2018