Honestly, the promotion had a lot to do with simply being in the right place at the right time. Yet I also didn’t just receive that promotion. I didn’t realize it at the time, but certain actions I was taking had fortuitously positioned me to seize an opportunity that fate dropped into my lap.

I didn’t show up day after day and eventually receive a promotion due to seniority. I didn’t receive that promotion because we were a small business that required low-skill bookkeeping. We were a multistate, multilocation, and partly international organization with a complex ownership structure and six sets of unconsolidated financials. I achieved that unlikely promotion because, when the opportunity presented itself, I was mostly ready for it.

MAKE SURE YOU DREAM EMBARRASSINGLY BIG

When I was growing up in Michigan in the ’80s and ’90s, two of the biggest figures in business were Lee Iacocca and Jack Welch. In the 1980s, Iacocca was CEO of Chrysler Corporation, which was headquartered in Detroit, Mich. Chrysler was on the brink of going bankrupt. While there, Iacocca orchestrated one of the greatest turnarounds of all time, essentially rebuilding the entire company. He was the automaker’s last chance at survival back then, so he grabbed the attention of the world when he made it profitable again. And Welch was the CEO of General Electric during the ’80s and ’90s. During his tenure, the company’s value rose an astounding 4,000%. In addition to being a brilliant CEO, Welch is also an accomplished author. His 2005 book, Winning, helped me understand what a CEO should expect from senior leadership.

While Iacocca and Welch were dominating the corporate world, I was growing up poor on a small farm and in a dysfunctional family in which no one had ever received a college education. In spite of my surroundings and the low expectations the world had for me, I had secret dreams of greatness like many young people do. But instead of dreaming about becoming a famous actress, a princess, or a supermodel, I dreamed of being like two old men: Lee Iacocca and Jack Welch, success stories of their day. And while I’m neither of them, I’m proud of where I am.

Growing up as I did, I had no idea how to become a business leader. I had never known one. As a high school student, I didn’t apply to colleges, visit university campuses, or search for scholarships. I simply had a secret vision in the back of my mind that, because of my life circumstances and lack of knowledge, seemed unrealistic and unattainable. I worked hard; read hundreds of books about great women and men, business, history, and leadership; pursued my vision; was persistent; and took some risks.

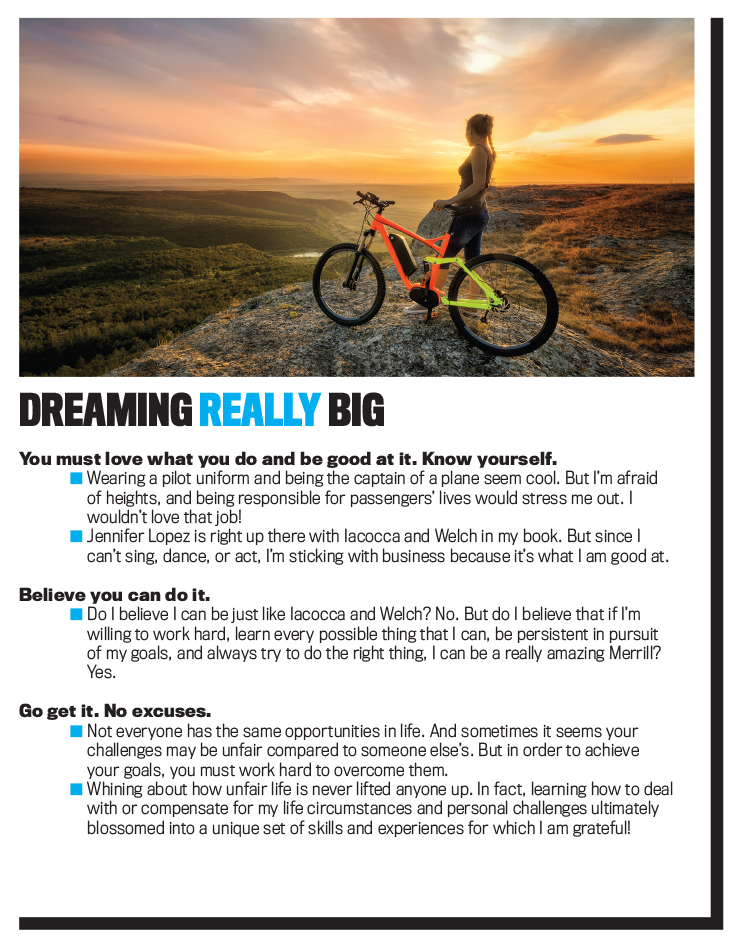

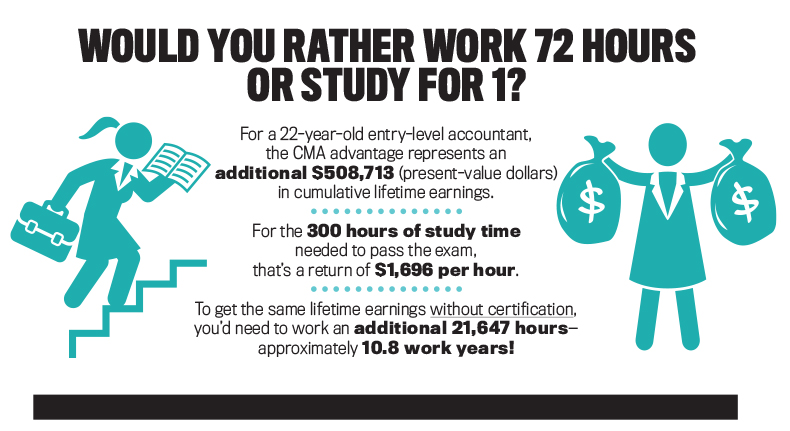

If you want to rise to the top, you must start by dreaming big. Really big. (See “Dreaming Really Big”) If you think your goal is that you want to be a professional accountant, that’s good. Write that down, then cross it out and think about what’s above that. Maybe middle management? That’s a better goal. Write that one down. Now cross that one out, too. What’s above that? Earning your CMA® (Certified Management Accountant) certification? Moving on to senior management? Controller? CFO? You get the idea. Don’t stop dreaming to the next level until you get to the point where, if someone asks you what your career aspirations are, your dream is so big and bold that you are embarrassed to admit it.

ALWAYS PURSUE MORE

In pursuit of my big dream, I wanted to learn how to be a great business leader, but I knew nothing about how business worked. When I got my first accounting job, I decided that, since I didn’t know anything, I’d try to learn everything. In my staff accountant role, I had many repetitive tasks, such as managing accounts payable and payroll for multiple companies. I found ways to streamline the processes from the beginning when invoices or payroll data was received at headquarters all the way through until the disbursements were filed. This included revamping the filing system.

Anywhere there was a repetitive process, I found ways to speed it up so that I would have more time for more important things—like learning! I spent the free time I built up learning from all parts of the organization, but I spent the most time with my boss, the controller. I frequently asked him for more work to do, and he obliged. Eventually, he ran out of tasks to give me, so I asked that he let me observe his performing some tasks that only he could do.

Imagine having some eager beaver standing over your shoulder, watching and emulating your every move. I expect this could have been unnerving for some, but, fortunately for me, he was happy to do so. And I was happy with this because just knowing what a controller actually did all day was a step in the right direction for me.

Pursuing more means that you take meaningful action like asking for, and eagerly accepting, more responsibility at work. It means asking to observe the work of others and then doing so inquisitively. Whenever I start a new job, I always spend time learning about what people in other departments do. It doesn’t matter that I’ll never have to do what they do (fabricating steel, producing a simulcast, selling an insurance policy, or cleaning a movie theater). Understanding what they do and how they do it helps me understand the business as a whole. If you want to rise to the top, it isn’t enough to know your role and your department inside and out. You must also be able to at least have a conversation about what goes on outside your department with other leaders in the organization.

Six months into my first accounting job, I had learned a lot about how the various businesses in the group operated. I had spoken with many of the leaders in the organization and had observed all that I was able to observe locally. I was doing all my work and some of the controller’s work, and I was learning about a few of his responsibilities that I couldn’t actually do by myself. Then, out of the blue, having accepted another position elsewhere, the controller resigned.

BE BULLDOGGISH

When the controller resigned, I went to see the CEO, to whom the controller reported. I explained that I had already learned how to do much of what was on the controller’s job description and that, therefore, although young and inexperienced, I believed I was capable of doing the job. He didn’t laugh at me, but he did tell me that he wouldn’t even consider me for the position.

A day or two later, convinced that I had failed to effectively communicate the depth of training I had received, I talked to the CEO again. He still wouldn’t consider me for the controller position, but this time he told me specifically why, and this ended up being the key. He said he liked me, he thought I was a good worker, and because of that he wanted me to continue to be an employee of the group long term. If he promoted me to controller, we would backfill my current position, and if I failed because I wasn’t ready, then he’d have to fire me because I’d have no position to return to. In other words, if I failed, I couldn’t go back, and he wasn’t willing to take that risk.

It was time to change tactics. A day or two later, I went back to see him again, this time armed with a business proposal that he couldn’t refuse. The pitch was this: I was so confident in my ability to do the job to his satisfaction that I would do both the controller job and my current job simultaneously for however long it took for him to feel confident about my abilities. Only when he was comfortable with me in the controller seat would we backfill my previous position. And that’s how I got promoted to controller in six months.

Many years later, when preparing to transition from one job to another, I conducted exit interviews with my staff in order to get feedback about my management style. At first I was surprised when a subordinate described me as “bulldoggish.” She said when I “latched onto something” (a project, a problem, or something I wanted accomplished), I wouldn’t let go of it even if it was obvious to everyone but me that it wouldn’t work. This frustrated her and the team at times. But in spite of the team’s resistance, I would keep driving them forward, finding workarounds and trying new things until we finally achieved our goal: a completed project, an improved process, etc. She said it was from those experiences that I earned her respect and demonstrated the success found in perseverance.

TAKE WILD AND CRAZY RISKS

I refuse to go skydiving or bungee jumping. I don’t like roller coasters, and the one time I went zip-lining I almost got sick. As far as I’m concerned, some risks just aren’t worth taking. But risk-free opportunities in life just don’t exist. In the race to the top, you must be willing to take a leap of faith.

When I was in that first controller position, I had it pretty good. I was making a reasonable wage for my experience, I had my own office and a good boss, and I worked with some really smart people. I even had a company car. (Full disclosure, it was a retired VP’s hand-me-down with almost 200,000 miles on it, but still.) So when the opportunity came along for me to become CFO of a small business that was really struggling to make ends meet, taking that job seemed like a crazy idea. But I saw my opportunity to make a difference—to play a part in a great turnaround like Iacocca or Welch (albeit on a scale that was miniscule in comparison)!

I knew the owner very well, and, after learning about the business, I decided to take that leap of faith. It was a huge risk, but I didn’t see that sort of opportunity coming along for me again that early in my career. As it turned out, that CFO role and the knowledge I gained from it ultimately shaped the rest of my career. Never in my life have I learned more from an individual (the owner) or an organization as I did in the years I held that position.

I’ve taken risks like this in my career several times since then. Every time you change jobs, you’re taking a risk. The key is to do tons of research beforehand, and if it isn’t a good fit, don’t do it. My risks haven’t all paid off. There are some I wish I wouldn’t have taken, but I have, without question, gained more than I’ve lost.

The pursuit of greatness must begin with a passion that burns hot enough and long enough to fuel this journey in which you must endure both victory and defeat and everything in between. Hard work, preparation, initiative, persistence, and calculated risk taking are all necessary to position you to confidently seize opportunities that come your way. They will also keep you moving forward instead of backward when you face inevitable obstacles.

January 2018