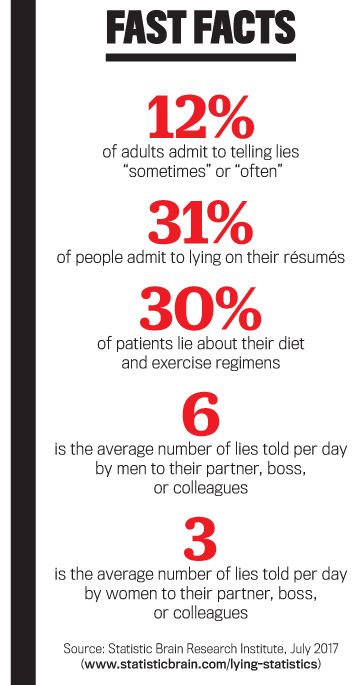

Believe it or not, a 2016 study of social media in the United Kingdom found that more than 75% of respondents admitted to lying about themselves on their social media profiles. This finding is consistent with those of an older study conducted by a University of Massachusetts psychologist, which found that 60% of adults can’t have a 10-minute conversation without lying at least once; in fact, they typically tell an average of two to three lies in this short span.

Pamela Meyer, author of Liespotting: Proven Techniques to Detect Deception (St. Martin’s Press, New York, N.Y., 2010), goes even further, adding that humans lie about 200 times per day. In addition, 90% of children have a clear understanding of lying by the age of four. This may seem a bit twisted, but we learn to lie early in life because lying actually facilitates social interactions. Surprisingly, most of us learn from our parents how to lie. For example, when kids receive a gift they don’t like from a friend or relative, the parents often encourage them to lie about their feelings. Knowing when to remain silent or to tell a white lie is, in fact, based on a social belief that we don’t want to hear hurtful things.

Granted, most lies don’t have serious consequences or aren’t very important. At least that’s what we tell ourselves. Quite often we lie about trivial issues that have little significance (“You look nice today!”). Perhaps we lie to try to impress someone—to make ourselves look better than we actually are. For instance, several studies (and a pile of anecdotal evidence from those who have been deceived) indicate that people looking for a date online stretch the truth when constructing their profile. Maybe we lie because it’s just easier or more expedient to lie than to drag out a complicated, unimportant story that we know won’t matter anyway.

On the other hand, lies can create problems that result in extreme damage in various dimensions of our lives, such as with personal finances, work relationships, marriage, and emotional and trust issues. (For more, see “Who Isn’t Telling the Truth?”)

LYING TO YOURSELF

Remarkably, people engage in a significant degree of self-deception, an unconscious process that we humans use to protect ourselves. We may use it to diffuse the anxiety or discomfort when we realize that “who we really are” isn’t “who we think we are” or “who we think we should be.” (For more, see Neel Burton, “The Psychology of Self-Deception,” Psychology Today, August 28, 2015.) Studies show that people who deceive themselves tend to be happier than people who don’t. Some people believe this is actually helpful in that they’re able to convince themselves that they can perform better. And there may be other benefits of lying.

Here’s one: People who lie tend to be more popular, according to the University of Massachusetts study cited earlier. And embellishment-as-lying has other benefits. In interviews, college students who exaggerated their GPA later showed improvement in their grades. Further, “exaggerators tend to be more confident and have higher goals for achievement,” according to University of Southampton (England) psychologist Richard H. Gramzow, who concluded that “positive biases about the self can be beneficial.” Yet, oddly enough, despite how frequently we stretch the truth, our overall psychological health improves when we tell fewer lies. (For more, see Kare Anderson, “Seven Somewhat Unexpected Truths About Liars and Lying,” Forbes, June 1, 2013.)

WHY SHOULD ACCOUNTANTS CARE?

It’s no secret that many organizations lose money to fraud. When a company experiences a shortage in cash or inventory, the management accountant or loss-prevention personnel start an investigation to determine the culprit by interviewing employees who have responsibility for, or had access to, the missing assets. This is a critical part of the investigation. Being able to detect lies during the interviews will help the company narrow down the pool of suspects.

Other situations that can test a management accountant’s ability to detect lies are the budgeting process and transfer pricing. Both of these processes are involved with a considerable amount of information exchange and negotiation but are realized internally between two or more parties. Being able to assess the reliability and credibility of the information offered by these parties is instrumental in achieving the desired outcomes.

Given the importance of lie detection to accountants, it’s surprising that most universities don’t teach deception-detection techniques as part of their accounting curriculum. In fact, many accountants regularly conduct interviews at work without any proper training in deception-detection or interview techniques. This suggests that, as educators, we should perhaps consider training in these areas. (Companies that provide this instruction are mentioned in “Interrogation 101, Anyone?” below.)

CAN YOU DETECT DECEPTION?

Researchers across the globe are actively trying to become proficient at reliably detecting deception and lying. While many facial expressions are universal, they last only a fraction of a second and thus provide only marginal value in spotting deception. Even people with special training can easily misinterpret the correct outcomes.

Liars often focus on controlling verbal statements. Therefore, previous research has often been couched in the area of nonverbal behavior (i.e., body language) and the assumption that it’s difficult to control and therefore may be a clue to an intention to deceive. For example, in 1993 the Supreme Court of Canada concluded that judges and jurors “must view” a witness to adequately evaluate body language, deeming these expressions as vitally important to assess the witness’s credibility.

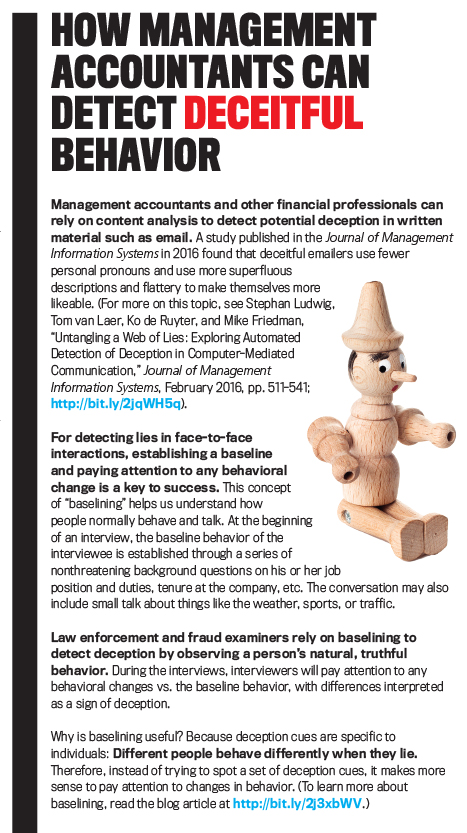

When judges and jurors can see a witness’s entire body and face and hear his or her statements, they not only can observe individual behavior, but they can also detect any discrepancy among verbal and nonverbal behavior. For example, a witness may say “yes” to a question but roll his or her eyes at the same time. As a management accountant, you, too, will find yourself in a position of having to determine whether someone’s being truthful with you or twisting the facts to suit his or her own aims. Some tips to help you handle these situations can be found in “How Management Accountants Can Detect Deceitful Behavior” and “Additional Resources.”

CONTENT ANALYSIS AND TRUTH BIAS

Not surprisingly, when it comes to deception, what individuals or organizations express verbally has the same ability to give them away as any sort of body language.

Content-analysis software can examine emails and other communications for changes in verb tense and other details that can indicate an attempt to mislead or outright deceive. Our own previous research and experience have been centered more on written indicators for prediction, and we’ve achieved significantly accurate results using these cues.

Our fraud-detection model includes four variables describing characteristics of fraud in companies’ communications: (1) more words, (2) fewer colons, (3) fewer positive-emotion words (happy, pretty, good) and more negative-emotion ones (worthless, poor, bad), and (4) fewer present-tense words. In an article published in Strategic Finance in 2013, we reported that for healthy companies in our sample, their Management Discussion & Analysis (MD&A) contained an average of 17 negative words, while WorldCom, Enron, and Tyco averaged 61 negative words. (To learn more details about the application of these words to MD&A, see Chih-Chen Lee, Natalie Tatiana Churyk, and B. Douglas Clinton, “Detect Fraud Before Catastrophe,” Strategic Finance, March 2013, pp. 33-37).

Our mission was to discover reliable ways of detecting fraud before devastating financial results occurred. Although this is often an auditor’s job, we suggested that management accountants have a major role to play, too. We asked: “What could be achieved if management accounting professionals could identify fraudulently misstated information before using it?” Quite simply, they could provide better decision-support information to management, improve risk assessment, and enhance their contribution to enterprise optimization.

Another concept that comes into play when deciding whether something is true or false is called “truth bias,” which is essentially the tendency that people want to believe what others are telling them. This is perhaps the main reason why most people are poor lie detectors. Unless they’re fairly confident that someone is lying, most people would rather err on the conservative side and assume that the other party is telling the truth in order to ensure smooth social conversations and interactions.

Calling someone a liar can potentially damage a relationship that took years to establish, even if the accusation turns out to be false. In many situations, it may be easier to trust another’s statement, especially if the cost of trusting isn’t that high. The potential downside of mounting a challenge just may not be worth it.

KEEP YOUR GUARD UP!

Although certain behavioral cues are offered to help people detect deception, none of these cues can stand up to empirical testing in different contexts with different people. For example, many experts believe that identifying eye movement and direction can reveal truth or lies. They claim that when someone looks up and to the left when asked a question, the person may be visually constructing information instead of recalling facts for an answer, which would indicate lying. A liar, however, is likely to rehearse his or her lies in advance, then provide a canned response to any questions related to the deception.

Perhaps the best advice we could give to improve your chances of detecting deception is to be a good observer, using both your eyes and your ears to spot departures from baseline behavior. One widely accepted premise from the early 1980s that’s still true today is that no single behavior or set of behaviors always occurs when people are lying.

And while not scientific in any way, trusting your instincts may serve you well, too. If something doesn’t sound right to you and you suspect dishonesty, do some due diligence to get to the bottom of things before contemplating your next move, especially before saying something you might regret later. Depending on the gravity of the situation and the quality of the information you’ve been handed, your reputation—and that of your organization—may depend on it.

Who Isn’t Telling the Truth?

- According to HireRight’s 2017 Employment Screening Benchmark Report, 85% of human resource professionals reported they’ve caught a lie or misrepresentation on a résumé or job application. This is up from 66% of survey respondents five years ago (hireright.com/benchmarking).

- One in four New Yorkers believes it’s acceptable to lie to an insurer, reports the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud (insurancefraud.org/statistics.htm).

- Closer to home for accountants, one in three (36%) organizations reported being hit by economic crime in the last 12 months, according to PwC’s 2016 Global Economic Crime Survey (https://pwc.to/2Bd0IoK).

- From the same PwC study, one in five respondents said they were unaware of any formal ethics and compliance program at their firm, even though 82% of companies reported having a formal plan in place.

- Overall, deception costs businesses $3.7 trillion per year—roughly 5% of annual revenue, according to the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners.

Interrogation 101, Anyone?

Want to learn more about interview and interrogation techniques to improve your ability to obtain the truth? If so, training is available. Here are a few companies that offer interviewing and interrogation training programs and consulting services:

Wicklander-Zulawski & Associates (www.w-z.com)

John E. Reid & Associates (www.reid.com)

The CTK Group (www.thectkgroup.com)

Additional Resources

- Think you can spot the fake smile? Take this online test: surveymonkey.com/r/SmileRead.

- If you didn’t do well on the test, these videos can teach you more about identifying a fake smile: http://bit.ly/2jpB45F

- Pamela Meyer, the author of Liespotting: Proven Techniques to Detect Deception, provides a quiz for people to test their “Lie-Q”: http://bit.ly/2ACQP0u and http://bit.ly/2joMPZR.

- Susan Carnicero, a former security expert with the Central Intelligence Agency who is a founding partner of QVerity, gives an engaging talk on detecting deception: http://bit.ly/2iDI3qO.

- Carol Kinsey Goman, the author of several books on body language, discusses how to spot liars in the workplace—and how to deal with them: http://bit.ly/2AlrWcU.

January 2018