Business schools must consider an even longer horizon. Given the pace of adaptation in higher education, colleges and universities must contemplate the next decade as they craft curricula to anticipate the knowledge and skills that employers will expect from graduates.

Recognizing this need, the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) created International Accounting Accreditation Standard A7, “Information Technology Skills and Knowledge for Accounting Graduates,” which requires accredited accounting programs to deploy and document learning strategies to develop graduates’ competencies in data analytics, data management, and other business information technologies. But how do leading business schools polish their crystal balls as they integrate these competencies into their future curricula?

RETOOLING A STANDARD CURRICULUM

Because Big Data is pervasive, we and our colleagues at Grand Valley State University (GVSU) in Grand Rapids, Mich., comprehensively analyzed how data management and data analytics fit into the school’s accounting courses. For this analysis, GVSU’s School of Accounting sought guidance from several sources:

(1) the Pathways Commission’s Recommendation #4 report, “In Pursuit of Accounting’s Curricula of the Future”;

(2) a PwC white paper called “Data Driven: What Students Need to Succeed in a Rapidly Changing Business World”;

(3) “Pre-Certification Core Competency Framework” from the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA);

(4) GVSU’s accounting faculty; and

(5) GVSU’s School of Accounting advisory board.

Formed in 2010 as a joint effort sponsored by the American Accounting Association (AAA) and the AICPA, the Pathways Commission has endeavored to develop visionary recommendations for the future of accounting education. Although the Commission isn’t focused solely on data analytics, its recommendations provide tremendous insight regarding the data skills and professional judgment that businesses will need from future accountants.

Our team at GVSU focused on the Pathways Commission’s fourth recommendation to “develop curriculum models and engaging learning resources and mechanisms for easily sharing them as well as enhancing faculty development opportunities in support of sustaining a robust curriculum” and, more specifically, Action Item 4.1.6: “Transform learning experiences to reflect current and emerging technologies and global trends in business.”

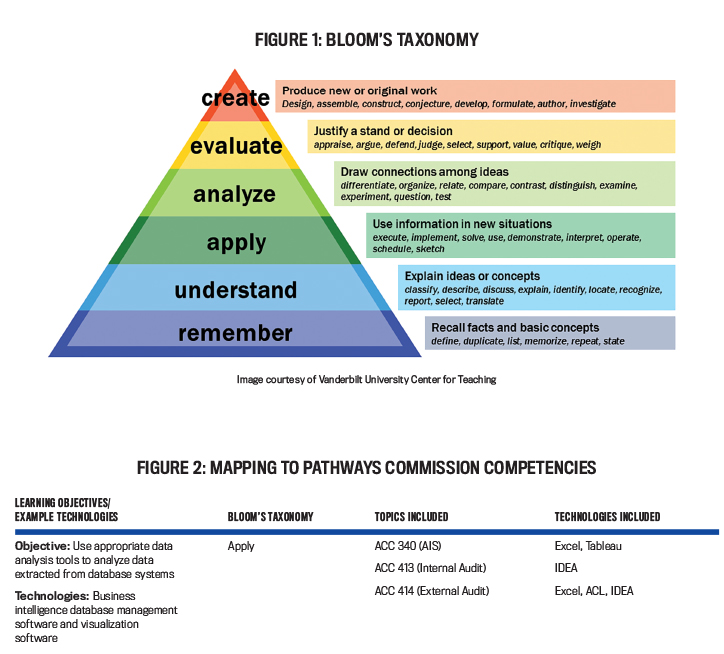

The Pathways Commission outlines competencies according to learning objectives and their associated hierarchy, as defined by Bloom’s Taxonomy (see Figure 1), which suggests that students should be able to REMEMBER facts and concepts at the most basic level of learning, propelling them at some point to be able to CREATE new or original work at the highest level. In between those two extremes, students should progressively be able to UNDERSTAND, APPLY, ANALYZE, and EVALUATE information. At GVSU, we endeavor to permeate our accounting curriculum with each of these elements to prepare graduates with the types of analytics skills that employers will demand from them.

ROLLING UP OUR SLEEVES

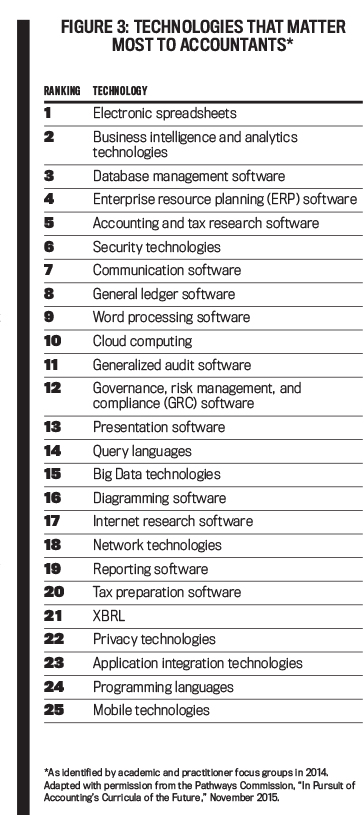

GVSU extracted learning objectives (or competencies) related to data management and analytics from the Pathways Commission’s report, appended examples of specific types of technologies that could help meet those learning objectives, added competencies from other previously noted sources, and asked faculty to map each competency to specific undergraduate and graduate courses. This exercise was invaluable for determining areas where the accounting courses do a good job of addressing the desired competencies while uncovering opportunities to enhance the curriculum in certain areas. Figure 2 (above) shows an excerpt from the mapping.

We were particularly intrigued by the top 25 technologies (see Figure 3) the Technology Task Force of the Pathways Commission identified during 2014. Specifically, the six practitioner and five academic focus groups were asked, “What technologies should accounting students know to be successful in the accounting workplace?” We realized that these technologies provide a solid benchmark for evaluating and enhancing our accounting curriculum because they identify skills that stakeholders desire. And they were prioritized! Even though the Pathways Commission’s report indicated a strong consensus for certain technologies (electronic spreadsheets, for example) and a significant difference of opinion regarding the importance of other technologies, this list represents salient areas that colleges and universities should incorporate into their accounting curricula.

As GVSU mapped its curriculum, faculty verified that the university already covered some technologies extensively. For instance, electronic spreadsheets are pervasive in a variety of our business and accounting classes. The same goes for database management software, such as Access and SQL. Students routinely use research software for both financial accounting and taxation. Presentation software, such as PowerPoint, Prezi, and Google Slides, is nearly ubiquitous both inside the classroom and for external activities, including juried presentations that Intermediate Accounting students present to practicing CPAs. Moreover, our auditing courses require students to use generalized audit software (GAS).

We also identified opportunities for improvement. For example, we agreed that the school should enhance its utilization of business intelligence tools that harness the power of predictive analytics. Privacy technologies, too, have become increasingly important because data is much more accessible these days and the number of data breaches is rising. Another example is GRC software, which deserves attention for its ability to facilitate organizational governance, risk management, and compliance. These are just a few competencies a forward-looking curriculum should consider.

Naturally, some software is subject to pedagogical debate. For example, the Pathways Commission’s focus groups identified tax preparation software as one of the top 25 technologies. Because practitioners routinely use software such as ProSystem fx and UltraTax CS to prepare tax returns, it’s only logical that students should be exposed to such software. Yet some educators struggle with students’ ability to truly understand certain key nuances of tax law if software is performing all the calculations. Just as children may need to learn long division manually, students may best learn accounting by pencil and paper during their formative stages. In short, college educators need to creatively hone courses to preserve students’ comprehension of core concepts while exposing them to technologies that they’ll use on the job.

THE TIMES ARE A-CHANGIN’

Although Bob Dylan wasn’t prognosticating about data analysis when he wrote about changing times more than 50 years ago, accountants should nonetheless heed his warning. Jim Boomer, CEO of Boomer Consulting, cautions accounting firms to beware of professional obsolescence as technological innovation and Big Data shift firms’ value propositions. He notes that “below the line” services, such as tax preparation, accounting, and assurance, will become increasingly commoditized as technology replaces the roles of flesh-and-blood accountants. Boomer, who’s an expert on managing accounting technology, argues that successful firms must be ready to provide “above the line” services that include business advisory, strategic planning, and mergers and acquisitions. Educators must therefore help students harness the power of data analytics and prepare them to exercise enhanced professional judgment after graduation.

Let’s look at how this plays out in the auditing world. Auditors know that sampling risk translates to audit risk and ultimately to engagement risk. Because of the inherent limitations associated with examining less than the entire population of data, an auditor’s opinion can only convey reasonable, not absolute, assurance. GAS packages mitigate sampling risk by allowing auditors to perform tests on an entire population of data as an alternative to sampling. Consider an examination of journal entries for proper authorization. The legacy technique of attributes sampling allowed auditors to obtain a subset of journal entries to examine manually. GAS, on the other hand, lets the auditor test all journal entries for authorization, thereby eliminating sampling risk.

A beauty of GAS is its ability to transcend a specific enterprise resource planning (ERP) or general ledger software; an auditor doesn’t need client-specific software for tests and analysis. GAS allows auditors to quickly perform a variety of procedures, such as highlighting duplicate transactions, comparing vendor addresses with employee addresses, stratifying, sorting, summarizing, and even applying Benford’s Law to determine whether a particular digit occurring in a specific sequence within data values is improbable (and therefore suspicious). Because audit firms expect college graduates to be proficient with GAS, our university has incorporated both CaseWare IDEA and ACL Software into its auditing courses.

WITHOUT DATA, WE’RE NOTHING!

Data is the beating heart of analytical procedures, which not only are fundamental to audit and review engagements but also offer insights elsewhere in accounting. Analytical procedures require the prediction of financial statement amounts based on plausible relationships between financial and/or nonfinancial data. For example, an auditor could use employees’ hours (a nonfinancial measure) with pay rates (a financial measure) to predict a client’s payroll expense (another financial measure). Auditors must use analytical procedures during the planning and final review stages of an audit. They also have the option of including substantive analytical procedures as evidence to support their audit opinion.

Codified auditing guidance reminds practitioners to ensure that a predictive relationship exists; correlation doesn’t necessarily indicate causation. AU-C Section 520, “Analytical Procedures,” specifically cautions that “the reasons that make relationships plausible are an important consideration because data sometimes appears to be related when it is not, which may lead the auditor to erroneous conclusions.” This fundamental lesson is critical because predictive analytics require cost drivers that truly cause costs to change.

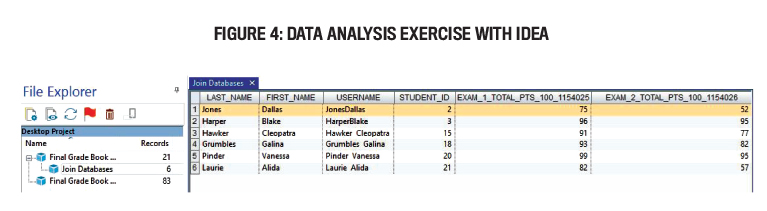

GVSU introduces auditing majors to data analytics with an exercise that requires them to use GAS to identify records with particular attributes, such as the number of students who earned an A- in a given semester or the names of students who earned the top five scores on an exam. Students also learn to join data sets by identifying students enrolled during both semesters. This exercise (see Figure 4) is a stepping stone that sets the foundation for subsequent analysis cases.

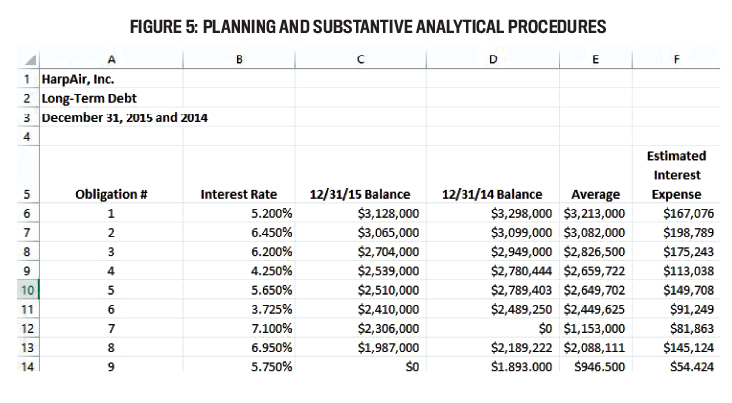

External auditing students complete several cases using GAS and/or Microsoft Excel, including one that requires them to search for irregularities involving cash disbursements for student tuition assistance. Another case, designed to familiarize them with planning analytical procedures, asks students to examine location-specific inventory and sales revenue to identify retail locations with unusual inventory and/or sales revenue. This serves as a simulation for risk assessment and audit planning. In another case, students use GAS to perform audit tests involving open accounts receivable invoices, customer credit limits, and shipping data. Yet another case, depicted in Figure 5, exposes students to both planning and substantive analytical procedures as they predict an audit client’s interest expense using debt balances and weighted-average borrowing rates. These cases and others like them illustrate data analytics while allowing students to develop the mind-set of professional skepticism that’s critical for successful accountants.

A BEVY OF ANALYTICS

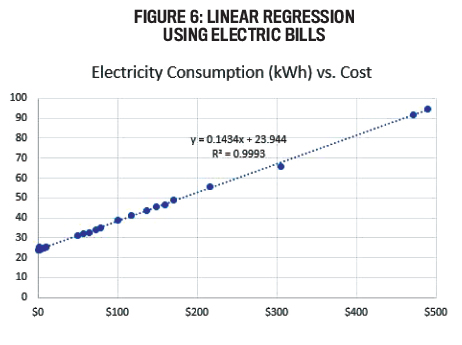

Management accounting is rife with data analysis opportunities. One GVSU instructor developed a case that requires students to analyze historical electricity costs and consumption data to predict future costs. Students use businesses’ actual electricity bills and regression analysis to describe a mixed cost that has both a fixed-cost component, for basic access to the utility grid, and a variable component, based on kilowatt-hours of consumption (see Figure 6). Students obtain firsthand experience with the power of prediction!

As you’re likely well aware, managers can use data analysis to discover anomalies within large data sets. One of our instructors illustrates this using a construction company that has several hundred fuel credit cards for its drivers of company vehicles. In a scenario like this, data analysis can be a hero in that it can highlight fraudulent use of fuel cards more efficiently than a manual reconciliation of purchases. For example, the company can compare transaction activity with expected fuel economy for particular types of vehicles to identify outliers that warrant further investigation—like the employee who routinely fills both his company car and his personal vehicle using the company’s fuel cards.

Taxation is another area to think about when it comes to data analytics. Consider the complexity of a modern tax return. One of our accounting professors recently examined his 2017 individual income tax return, and the PDF file is 133 pages long! Many nonaccountants (and accountants as well) who do their own taxes would be unable to comply with the complexity of today’s tax code without assistance from some type of software.

Savvy tax practitioners rely on data analysis to provide value-added advice to certain clients. When the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 brought a 3.8% net investment income surtax and a 0.9% additional Medicare tax to high-income taxpayers beginning in 2013, tax professionals relied on data tools to identify clients who would need additional tax planning. By mining data for taxpayers with adjusted gross incomes in excess of specified thresholds, accounting firms and tax preparers are able to proactively advise clients who might be affected by new provisions.

But data analytics aren’t solely the realm of financial statement auditors. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) auditors routinely use analytics to estimate amounts that should be reported on tax returns. Take a car wash, for example. An IRS auditor could examine the business’s historical water consumption data to estimate the gross revenue that should be reported even if the business has a lot of cash transactions (which could easily be underreported).

NEXT STEPS

As you can see, colleges and universities must continue teaching accounting fundamentals while preparing students to leverage higher-level data analytics. The true value of analytics isn’t confirming what has occurred but rather using historical information to make informed decisions that will help an organization better achieve its future objectives.

But learning how to synthesize large populations of data and the mechanics of specific technologies is just one part of the process. Educators—not just at our institution, but everywhere—need to help students develop critical-thinking skills and professional judgment that allow them to be prognosticators instead of merely data historians. Because computing power is increasingly able to accomplish functions that human beings used to perform, students (and educators) must learn to play “above the line” where critical thinking, healthy skepticism, creativity, and professional judgment will determine which students will be successful in delivering value to employers.

Business schools also should consider cross-disciplinary opportunities. Because action is the desired outcome and Big Data is inherently multifaceted, accounting students will benefit from abandoning a silo mentality. Accounting doesn’t occur in a vacuum—it’s inherently linked to an organization’s operational, administrative, and strategic endeavors. Accountants must shift from reporting artifacts to more robust roles as providers of action-oriented information. Accounting students will benefit from projects and tasks that require them to collaborate with students in other business and professional disciplines.

DON’T FORGET THE BASICS

Schools must not lose sight of fundamentals as they enhance their curricula. For instance, data management is an important prerequisite for data analytics: Students who understand sound database design and data models will be better equipped to build dashboards, create visualizations, fully utilize GAS, and perform other analytics. Educators must also help students understand the context of data because conclusions and recommendations may be wildly incorrect if analytics don’t capture the essence of data and the environment it describes.

Finally, critical thinking and professional judgment will become increasingly essential in a business climate that’s rapidly replacing manual analysis with high-tech tools. Students must be able to evaluate the reliability and relevance of data with the ultimate goal of using data analysis as a tool for developing meaningful, action-oriented business decisions.

Building a Better Curriculum: How to Get Started

- Obtain a copy of the Pathways Commission’s report. Appendix A lists the various competencies your institution should consider as you develop your institution’s matrix. You can find this document at https://commons.aaahq.org/posts/c0a7037eea.

- Augment the matrix to include additional technologies and competencies that your institution and its future graduates desire.

- Add two columns to the matrix: one to identify courses in which you currently cover each element and the other to map courses in which you plan to cover specific elements.

- Have accounting faculty complete the matrix to map elements to your institution’s specific courses.

- Review the completed matrix to identify coverage gaps.

- Develop course enhancements to address identified gaps. (We encourage infusing the entire curriculum with analytics skills and technologies.) Some circumstances, however, may require the addition of entirely new courses.

- Encourage faculty to peruse the “Further Resources” sidebar below for options for curriculum materials and tools.

- Include a feedback loop that encourages regular assessment and further curricular revision with a goal of continuous improvement.

Further Resources

Pathways Commission report: “In Pursuit of Accounting’s Curricula of the Future” https://commons.aaahq.org/posts/c0a7037eea

AICPA’s Pre-Certification Core Competency Framework: www.aicpa.org/interestareas/accountingeducation/resources/corecompetency.html

PwC white paper: “Data Driven: What Students Need to Succeed in a Rapidly Changing Business World” www.pwc.com/us/en/careers/university-relations/data-driven.html

Hub of Analytics Education: www.hubae.org

AIS Educator Journal: https://aiseducators.org/journal

Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting (JETA): https://aaajournals.org/loi/jeta?code=aaan-site

August 2018