This article is based on a study funded by the IMA® Research Foundation.

If relying too heavily on emotions while making choices negatively impacts a company’s performance, how can we cope with this phenomenon? What can organizations do to encourage managers to think more slowly about how their emotions affect their decisions? What, in turn, can managers do to control their natural desires to work with people they like or to let emotions rule?

THE EFFECTS OF EMOTION

A recent research study that explored these questions, the details of which we’ll get into straightaway, has several important takeaways for management accountants and other financial professionals. First, emotions are important drivers of workplace decisions, and that’s true regardless of whether firms use performance-based pay that might encourage managers to ignore those emotions. Second, performance-based pay can lead managers to make more economically desirable choices, but, interestingly, the reason this happens isn’t a simple case of paying managers to ignore their emotions. Rather, performance-based pay leads managers to cognitively process information using brain regions associated with more analytical and deliberative decision making. Third, because the way compensation contracts are designed can affect the way that managers cognitively process decision-relevant information, it raises the possibility that other management tools—like procedural prompts, task instructions, or supervisors’ reminders to pay attention to particular pieces of information—might also help managers consider more carefully how their emotions factor into a decision.

The “big idea” that prompted this research is described in Daniel Kahneman’s popular book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, which summarizes research on cognitive processing during decision making. Kahneman provides evidence that, in a variety of everyday settings, decision makers are hardwired to respond to salient features of their environments, including emotional cues, and often make decisions based on these responses using automatic, less-effortful processing. Environments, however, can be structured to prompt decision makers to slow down and carefully consider all relevant information, including emotions, using more-deliberative, analytical processing. This inspired three coauthors of this article—Anne Farrell at Miami University, Joshua Goh at National Taiwan University, and Brian White at the University of Texas at Austin—to take this “big idea” into a workplace setting and research the impact of emotions on decision making and the strategies that can lessen any possible negative economic consequences for firms.

WHAT OUR STUDY REVEALED

In our two-part study, we looked at managers’ investment decisions when their emotional reactions conflicted with the economics of their choices—that is, when the best choice from the company’s perspective is to select an investment that goes against a manager’s emotions. The goal was to learn about the costs to companies when managers automatically rely on their emotional reactions when making decisions and to learn whether compensating managers based on the outcome of their choices—through performance-based incentives—could reduce these costs.

In each study, graduate business students played the role of managers who had to make a series of decisions about investment projects that two hypothetical colleagues proposed. For some decisions, the economically optimal option was proposed by a colleague to whom the manager had negative emotional reactions. In other decisions, the economically suboptimal option was proposed by a colleague that the manager had positive emotional reactions to. And in still other decisions, the manager had no emotional reactions to either colleague. In short, the studies presented situations in which the economics of the alternatives often conflicted with managers’ emotions. Participants were compensated with either a fixed wage that wasn’t dependent on the outcomes of the investment projects they chose or performance-based pay that was linked to outcomes.

While the first study used a homogenous group of graduate business students, which we’ll explain shortly, the second study used a more diverse group. Across both studies, when participants received a fixed wage, they chose the investment that was economically optimal only 46% to 66% of the time. Said another way, they often chose the economically suboptimal investment that allowed them to work with a colleague they liked, or avoid working with someone they disliked, 34% to 54% of the time.

But when participants were paid based on performance, the rate of economically optimal choices increased to between 59% and 83%. Notably, though, when participants had no emotional reactions to colleagues, they chose the economically optimal choice at least 95% of the time, regardless of how they were paid. Overall, these findings suggest that although performance-based pay can increase the frequency of best choices, managers still often rely on their emotions. That part of the research really confirms what we already know or suspect: Working with someone you like, or avoiding someone you don’t like, has benefits to the decision maker but can be detrimental to employers.

A PEEK INSIDE MANAGERS’ BRAINS

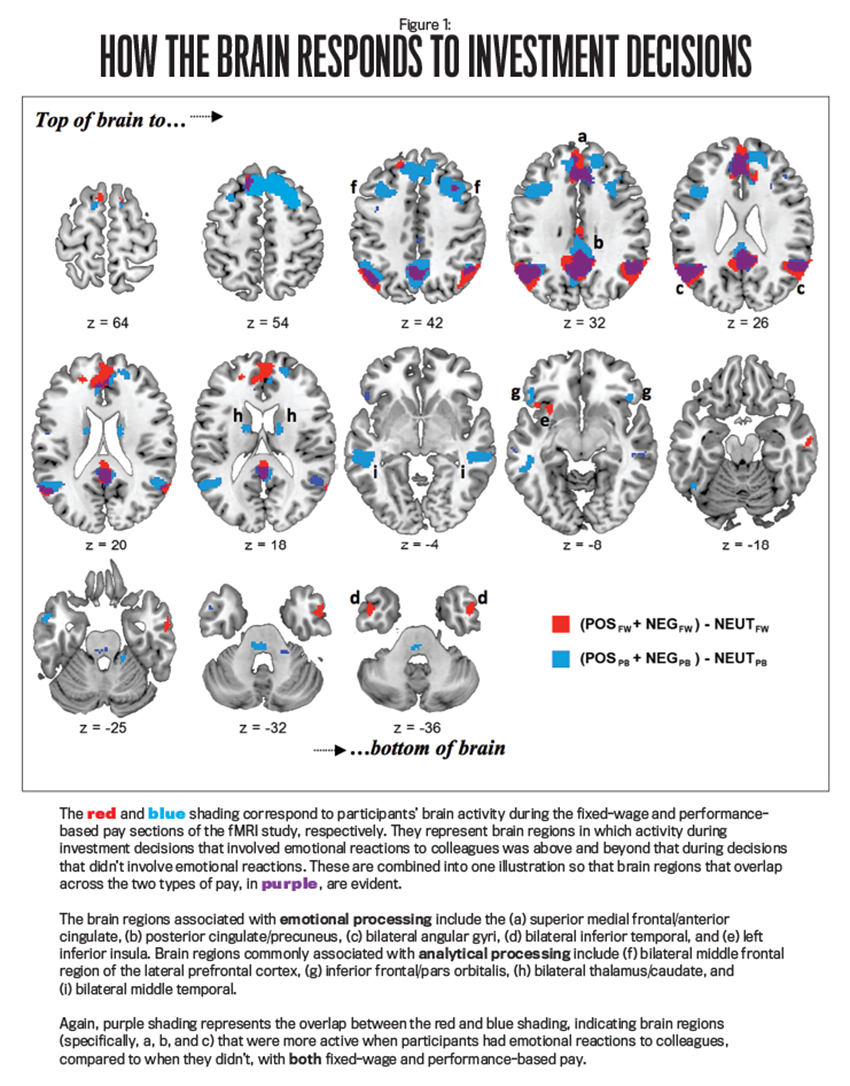

The part of the research that’s really neat, and adds to our understanding of managers’ decision making, is the “why.” To really understand what happens in the brain when the emotions and economics of decisions conflict, our research team observed participants in the first study in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner. This allowed the researchers to map regions of the brain that were active as participants made their investment choices depending on whether they received a fixed wage or performance-based pay.

If you know anything about neuroscience, you won’t be surprised that regardless of how they’re paid, when managers have emotional reactions to colleagues, regions of the brain—including the superior medial frontal, angular, and posterior cingulate regions—are active during decision making. These brain regions are thought to be centers for more-automatic, less-effortful processing that’s often based on emotional reactions. Interestingly, though, when managers receive performance-based pay that provides an incentive to consider the economics of their choices more carefully, many of these brain regions associated with automatic processing remain active, but there’s additional brain activity in the middle frontal, inferior frontal, middle temporal, thalamus, and caudate brain regions, which are associated with more-deliberative, analytical processing.

Performance-based pay motivates managers to make more economically optimal choices, and it does so by changing the way emotional reactions are processed in their brains. In other words, it isn’t all about the money; the incentives actually affect the way our brains process information that’s relevant to our decisions. Knowing this “why” can help us formulate better solutions to emotion-based decision making, such as prompts, procedures, or the “human element”—supervisors who remind managers to pay careful attention to their emotions before making decisions.

A STUDY OF RAPID-FIRE DECISIONS

How did our research team induce these emotional reactions in the lab? Prior to having our graduate student volunteers enter the fMRI scanner, we provided descriptions of two hypothetical colleagues with whom they had had positive interactions (for example, one who was a hard-working, dependable, thoughtful colleague), two with whom they had had negative interactions (for example, an arrogant, egotistical, condescending peer), and two with whom they had had neutral interactions. We provided names, photos, and backstories for these fictional colleagues (see below for an example) and checked that the participants had read and understood these stories. Once the participants were in the fMRI scanner, they made two sets of 90 rapid-fire investment decisions that appeared on a screen inside the scanner.

KEN: Arrogant, with an Ego to Match

Here’s a fictional backstory of a hypothetical business colleague that we asked our study participants to familiarize themselves with before presenting them with a series of investment choices.

In the recent past, you were impressed by a proposal that Ken had submitted to you, so you contacted him directly to discuss it. Ken’s attitude and tone during that conversation surprised you. Although you’re both division managers (and thus peers), he spoke to you as if you were his subordinate, using a condescending tone that you would never use with anyone on your team. For example, Ken told you that you should value the opportunity to work with him because he was a “key player at Universal” and that working with him would be a “great learning experience” for you.

You have enjoyed a very successful career with Universal—equally as successful as Ken’s, if not more so—and you certainly aren’t accustomed to being spoken to in such an arrogant and condescending way, especially by a peer. Nevertheless, after this conversation, you decided to give Ken the benefit of the doubt. The idea still seemed impressive, and, after all, you had never been formally introduced to each other, so perhaps Ken may have had the wrong impression about your level of experience within the firm or was simply having a bad day.

After that extremely unpleasant conversation with Ken, you hoped that a face-to-face meeting would ease your concerns about his attitude. The meeting with Ken, however, served to not only confirm, but also strengthen, your initial impressions. Although the meeting took place in your division’s conference room, Ken immediately brushed past you, seated himself at the head of the table, and instructed your assistant to “fetch” him a cup of coffee. Furthermore, while you had expected a fairly brief, conversational meeting, Ken directed one of his staff to “fire up the highlight reel,” an elaborate PowerPoint presentation listing details of his team’s recently completed projects, or “conquests,” as he insisted on calling them.

While you admitted to yourself that Ken’s track record was impressive, you couldn’t help but note that it was no more impressive than your own. When the “highlight reel” ended, you and your team listened in stunned silence as Ken gave you chapter and verse on the power of his “signature” management style. He was particularly keen to impress upon you how much more efficiently and effectively his division’s employees work than yours, a fact he attributed to the hands-on supervision he personally provided to each one of them, in contrast to what he derisively called your “too-soft mentoring approach.” Finally, after more than an hour of self-promotion, Ken and his team confirmed the original estimates in the proposal they had submitted, and you ended the meeting as quickly as you could.

In short, Ken is arrogant, egotistical, and condescending, making him a difficult person to work with.

The investment decisions paired one of the six colleagues the participants had been introduced to (the four emotion-based and two neutral colleagues) with 15 new, unfamiliar colleagues (hence, the 90 choices: six familiar multiplied by 15 unfamiliar colleagues). Each pairing included economic information about two possible investment projects proposed by the two colleagues pictured. If the participant had a prior positive emotional reaction to one of the colleagues on the screen, the expected economic payoff of that proposed investment project was lower; if the participant had a prior negative emotional reaction to one of the colleagues on the screen, the expected economic payoff was higher. In short, the choices based on emotional reactions were always economically suboptimal for the organization!

For their first set of 90 choices, participants earned a fixed wage: one lump-sum cash payment, regardless of what investments they chose. As described earlier, when emotions entered the mix, participants frequently chose projects proposed by managers they liked and dismissed projects pitched by those they disliked, even though it meant forgoing profits for the firm. In choices involving managers who weren’t associated with emotions, participants overwhelmingly selected investments that reflected the economics of the choices. Since participants earned a fixed wage, this pattern is easy to understand: There’s no personal economic cost to forgoing profitable projects, but there’s an emotional benefit in working with a great colleague or avoiding a terrible one.

After watching a Pixar film for a few minutes to distract them from the choices they had just made, participants again made the same 90 investment decisions but presented in a different order. This time, though, they received performance-based pay, earning cash for choosing economically optimal investments. As described earlier, this time participants made better choices but still not as many as they did when they had no emotional reactions to colleagues.

WHAT THE SCANS CAPTURED

While participants were making their investment decisions, the fMRI scanner was recording the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal. The BOLD signal measures the ratio of oxygenated (stimulated) blood to deoxygenated (unstimulated) blood in each brain region. Regions that are activated in response to a stimulus—in this case, the pairs of proposed investments—have stronger BOLD signals. When these BOLD signals were combined and analyzed across the participants, the pattern in Figure 1 emerged.

The regions of the brain highlighted in red are those that were activated when participants received a fixed wage; the regions in blue, when participants received performance-based pay. The overlap between these brain regions—those that were active regardless of the type of pay—is shown in purple. These results support the idea that when managers have emotional reactions to colleagues, there’s more automatic, emotion-based activity regardless of the type of pay. Importantly, with performance-based pay, there’s also more deliberative, analytic processing, with better economic outcomes for the firm.

In Study 1, to control for potential variations in the biology and functioning of brains of people with different demographic characteristics, the participants were all right-handed, native-English-speaking male graduate business students, which, while important for our study, obviously isn’t representative of the population of decision makers in the corporate world today. In addition, because the BOLD signal activates and disappears very quickly, our volunteers had to make rapid-fire decisions while in the fMRI scanner. While these features of the study were necessary because of the limitations of using fMRI technology, our research team wanted to be able to generalize the fMRI results. So we performed another study.

Participants in Study 2 were 96 graduate business students who didn’t participate in the fMRI study and had varying demographic characteristics. These “managers” made two investment decisions when receiving either a fixed wage or performance-based pay—not both. The two investment scenarios were similar to those in the fMRI task, but they included much more detail. Similar to Study 1, one choice paired an emotionally positive colleague proposing an economically suboptimal project with an emotionally neutral colleague proposing an economically optimal one; the other choice paired an emotionally negative colleague proposing a sound project and the emotionally neutral colleague proposing a terrible one. Once again, the emotions and the economics of the choices conflicted.

The results of this study support the same pattern of decisions found in the fMRI study: With a fixed wage, participants sacrificed economic gains to work with managers they liked or to avoid managers they didn’t like. Performance-based pay reduced, but didn’t eliminate, this tendency.

WHAT IT ALL MEANS TO YOU

This research has provided several important takeaways for companies that want to know more about how managers respond in certain emotionally charged situations. First, evidence from brain activity confirmed that emotions actually are important drivers of decisions, and it doesn’t matter how employees are compensated—that regularity persists. Emotional responses are hardwired into every person’s brain, so there may be ramifications to companies whose workplace environments heighten employees’ emotional reactions or that pit colleagues against one another. Rather than wishing that employees’ emotions would just go away, companies must acknowledge these responses and focus on developing ways to reduce their negative impact.

Second, while using performance-based pay is costly to companies, it leads managers to make more economically optimal choices. The reason, though, isn’t because the pay serves to stifle managers’ emotional responses. Rather, performance-based pay leads managers to use different brain regions—those associated with more-logical and intentional decision making—to process information. So performance-based pay may be effective in any company in which employees need to “slow down” their decision making to consider more carefully the importance of a variety of information (including emotion-based cues). For example, if certain managers have a strong tendency to rely on their gut instincts when making decisions, or if emotional factors easily sway their decisions, performance-based pay can help prompt more-deliberative decision making, align economic interests, and lead to more-profitable choices.

In addition, performance-based pay may benefit companies that rely on employee expertise in that experts may make too many decisions reflexively, based on their extensive knowledge and past experiences. Being aware of the likelihood of this can help companies and managers slow down the decision-making process.

Third, this new understanding of the effects of something the company has control over—the design of pay plans—raises the possibility that other factors the firm can control, such as monitoring, decision prompts, task instructions, or written or verbal commitments to conduct business in a certain way, can prompt similar processing changes and thus lead to greater economic benefits. Understanding other mechanisms that may activate the regions of the brain that analyze and consider information deliberately can be of great use to managers.

And you, personally? Maybe you’ll think about being the nice manager and the one whose work adds value to the company—the person everyone wants to work with and no one wants to avoid. Is there a downside to that?

September 2017