Uncertainty is unavoidable in the mercurial markets for entertainment. For Hollywood, that could be an upside; following conventional wisdom might divert you from success. In your finance department, however, uncertainty is a serious, hidden risk to the entire enterprise. Yet, as in Hollywood, you should ignore the conventional wisdom. It will divert you from managing this risk successfully.

The unnerving truth is that your finance department is probably managed less rigorously than your company’s office supplies. Finance departments routinely suffer from a lack of operational discipline that few CFOs would tolerate in any market-facing business unit. OpsDog’s research in Fortune 500 companies shows that 35% of the activities performed by knowledge workers is unnecessary and avoidable: error correction, rework, and over-service. This is equally true for finance departments. When this is pointed out, however, most CFOs dismiss it. It just isn’t obvious.

It might be easier to understand the problem by calling it an operational risk. CFOs must manage the financial risks of the corporation. It’s their fiduciary duty to prevent losses to the business and its shareholders. So it’s no surprise that CFOs, along with auditors and regulators, focus on identifying discrete events that cause losses, such as commodity price fluctuations, data breaches, cyberattacks, interest rate moves, and employee fraud.

Discrete events are already monitored with numerous operations metrics. Anyone with a credit card has experienced verification calls from the bank whenever it notices spending pattern changes. Many businesses exposed to commodities price risk use automated program trades to execute hedging strategies when a rate change occurs. And finance departments must comply with Sarbanes-Oxley regulations that monitor a wide range of risk events from boardroom oversight failures to financial reporting inaccuracies.

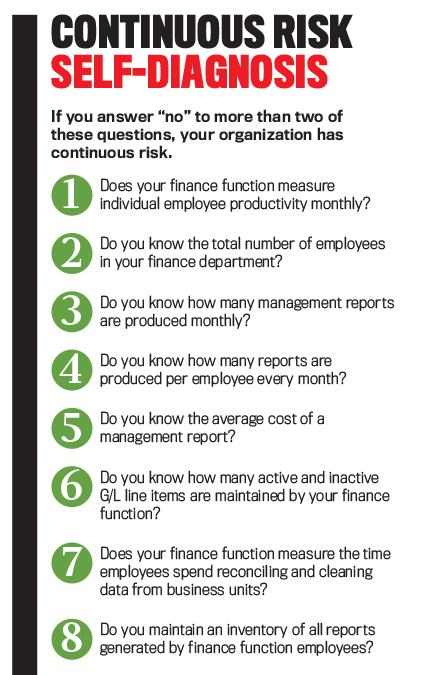

This intense surveillance, however, consistently overlooks a costly category of financial risk: continuous risk. This is the risk that goes unnoticed, often hiding in plain sight. It’s easy to miss because its characteristics are the polar opposite of the conventional discrete risk events that everyone targets. No one looks for continuous risks. No operations metrics are in place to monitor them. Although the corrections are valuable and simple, implementing them is extremely difficult.

While rooted in the operations of the finance department, the impact of continuous risk extends throughout the enterprise. It enables 20% of earnings to evaporate in the form of avoidable, low-value activities performed by highly paid knowledge workers. It also reduces overall business performance, an incalculable loss.

UNSEEN RISK

Recognizing discrete risks is simply a matter of time and study. It’s a straightforward process of rounding up familiar risk events and assessing the probabilities of losses from these usual suspects. These experiences lead to the identification of the characteristics of discrete risks. CFOs use these characteristics to identify other discrete risks, and they become more familiar, noticeable, and predictable.

Continuous risks, on the other hand, aren’t distinct events. They aren’t costly deviations from the status quo. Instead, they are the costly adherence to the status quo, especially when existing operations are riddled with expensive built-in errors, inefficiencies, and biases. Like viruses, these continuous risks inhabit and thrive in finance department operations. They pass unnoticed, unaudited, and unmanaged. This means that, as finance department employees do what they’re supposed to do, they unknowingly generate losses.

That lack of awareness and recognition also means the losses are unnoticed. It’s just business as usual, and the losses aren’t limited to the finance function. Most finance operations serve as “measurement factories” for the entire business. Therefore, losses from continuous risks degrade productivity measurement throughout every area of the company.

These losses from continuous risks can be grouped into two broad types: (1) direct and measurable losses and (2) indirect and unmeasurable losses.

Direct and Measurable Losses

The first loss from continuous risks manifests itself as unnecessary work activity performed by knowledge workers. These are avoidable, expensive labor costs. Think of the arcane complexity in the chart of accounts typical of most finance departments. This is a valuable inventory that directly feeds the measurement factories of management reporting. Yet it isn’t managed as an inventory. There are usually no instructions for creating, deleting, or even defining the accounts that make up this inventory. Imagine the avoidable activity that results—the reconciling, consolidating, and redefining of these accounts.

Research from OpsDog and the Fortune 500 shows that, replicated company-wide, this labor inefficiency alone siphons off an average 20% of a corporation’s earnings. These are earnings that have already been captured and exist inside the business. Yet before they can make their way to the bottom line, they’re squandered on costly, avoidable knowledge work tasks, such as error correction, duplication, and overserving customers.

Let’s look at two examples of direct losses. The first comes from one of the world’s largest retailers. Renowned for a world-class distribution network that runs like clockwork, the company installed an automated workflow technology with the ability to process accounts payable without human interaction. Approximately 95% of invoice processing was automated. Yet more than 2,000 employees spent their days manually processing the remaining 5%, the exceptions.

A few days of investigation revealed that 65% of these exceptions were “self-inflicted” by the finance department. This happened through confusing or missing instructions for vendor submissions of payables, lax enforcement of internal use of the workflow tool, and circumvention of the automated technology via email or hard copy. The direct cost of this unmanaged operational risk was that 1,300 employees were dedicated full time to remediation tasks that were completely avoidable, such as contacting vendors and researching purchase order terms. Half of these exceptions were eliminated in six weeks.

In the second example, a global securities broker maintained a vast internal management reporting organization that generated more than 50,000 recurring reports. This was more reports than the company’s total number of employees. Business managers requested and designed the reports, and the finance department fulfilled the requests, providing neither oversight specs for format nor analytical integrity. The cost of preparing these reports exceeded $200 million annually and was growing rapidly.

A brief review revealed a number of problems and opportunities. The complexity of the general ledger, including more than 350,000 items, was unmanaged. Half were active; half were inactive. But this recordkeeping was undisciplined. No inventory of reports existed. Addressing these factors alone reduced total reports by half within two months.

Indirect and Unmeasurable Losses

The second loss from continuous risks is the business underperformance that results from management reports prepared by the finance department. Visualize the unbridled proliferation of one-off management operating reports flooding out of the typical finance department. They are confusing, contradictory, and not standardized. Yet management must use them to fine-tune competitive performance.

Aspects of this loss can be quantified, such as customer service scores and market share loss, but the overall value lost by the inability to manage the business competitively is incalculable. With poorly designed and poorly calibrated reports that provide uncoordinated performance data, management visibility is limited.

This loss represents shortfalls against uncharted potential. Knowledge-worker operations aren’t automated enough. Workers in scheduling and maintenance, for example, don’t fully use tangible assets, such as production facilities. Because this loss isn’t visible, it’s easy for skeptics to look at results and point out that performance is as high as ever. Even with evidence of waste, it’s hard to argue that performance could increase to levels never seen before. It’s an opportunity cost. It’s why underproductive knowledge work businesses are vulnerable to competitive attacks from digital upstarts.

The following are two examples of indirect and unmeasurable losses. The first involves a top five global bank that maintained a worldwide network of customer contact centers. Executives in these centers designed and requested thousands of routinely recurring operating reports. The finance group produced them exactly as specified without oversight, standardization, or centralization.

The reports were of little value for improving operations in the contact centers. In fact, they could be counterproductive. For example, the demand patterns of incoming calls were difficult to compare with the staffing schedules. This created imbalances between available customer service representatives and inbound calls. Customers sometimes waited for almost 30 minutes. At other times, one-third of the representatives were idle. Contact center management requested no productivity reports, and the CFO’s staff neither suggested nor required them. The result was that service rep productivity varied sevenfold. The bank spent 25% more than peers on customer service but ranked in the bottom quartile on performance.

The second example is a Fortune 250 industrial manufacturer that overlooked a significant decline in unit volume sales of commercial products within a $3 billion division. This oversight happened because its management reports emphasized revenue growth. The company maintained a high-pressure sales culture. Most of its products were sold in institutional markets, such as governments and education. The company could preempt competitors by getting its high-quality products specified in original construction plans. Once this occurred, it was difficult for other manufacturers to displace the products. The entrenched vendor could raise prices. And it did.

The business managers specified the operating reports that the finance department prepared. No unit volume or productivity measures were included. The finance department dutifully prepared these reports by the hundreds. After all, the business unit was its customer, and the customer is king. The result: The business met or exceeded its sales and profitability targets. But it went too far. Low-price competitors managed to take nearly 20% of its market share over a 30-month period. Senior management failed to notice the volume declines.

A CFO ACTION PLAN

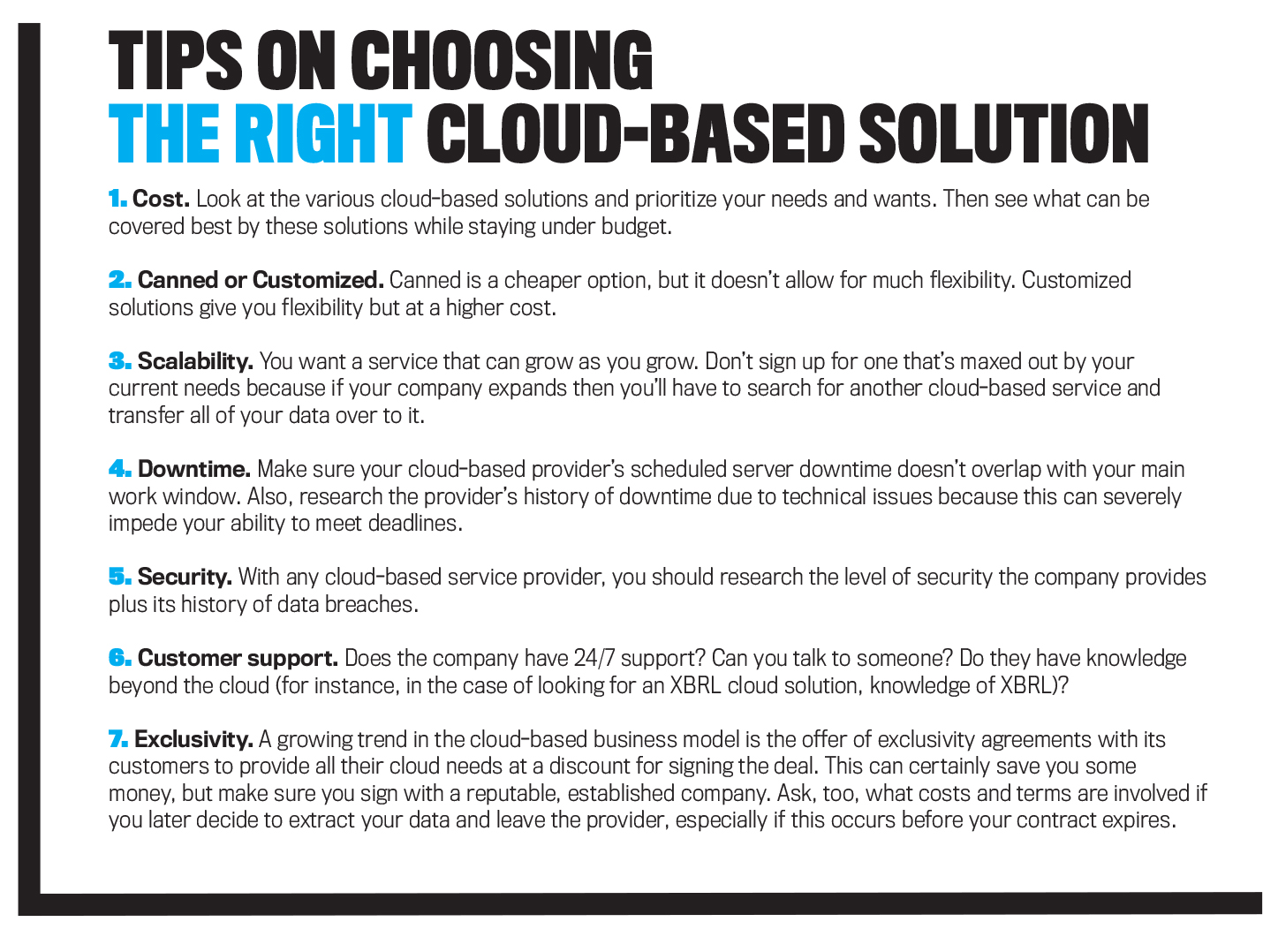

CFOs can begin to control continuous risks—those with both direct and indirect costs—by instituting four operational performance measures in their departments. These won’t require new technology, but they will require a persistent willingness to challenge the status quo. CFOs produce the instrumentation that populates the dashboards for management in the business units; it’s now time for them to comprehend the consequences and take full accountability for their related operations.

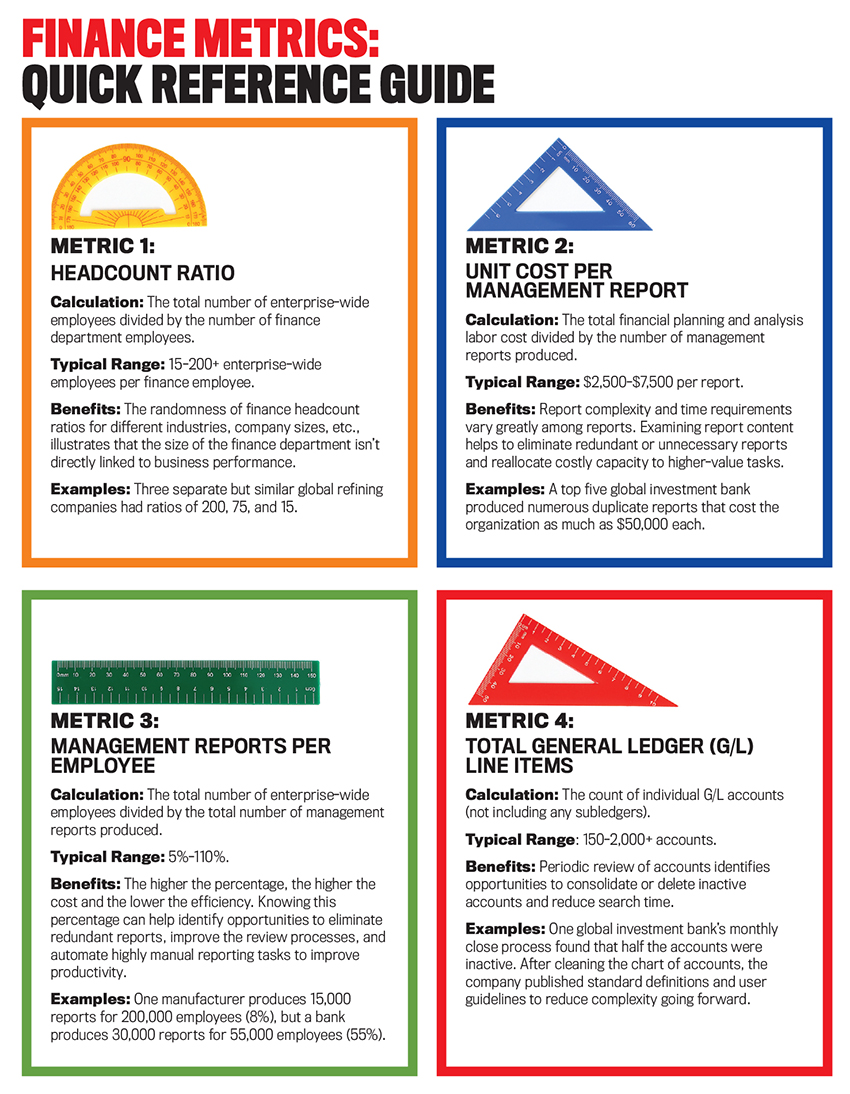

METRIC 1: Headcount Ratio

This first metric is the total number of enterprise employees divided by the number of finance group employees. The ratio will range from a typical low of around 15 to a high of well over 200. The value of this metric is how it helps illustrate the flaws in conventional thinking and prepares those in the finance function, particularly CFOs, to implement this new approach.

Conventional wisdom firmly maintains that a predictable relationship exists between industry type and the size of the finance department. Low-margin industries always have small finance departments; high-margin industries always have large ones. This thinking would lead to the conclusion that headcount ratios would have some kind of consistency or pattern.

When CFOs first encounter this metric, they will quickly calculate their organization’s ratio and find their location on the continuum. Being rational, they will search for explanations that explain the result. If they see ratios listed by company or industry, they will try to explain high or low ratios by industry characteristics. For example, they will speculate that highly competitive, commodity-style industries will be forced to maintain lean, low-cost finance organizations (higher headcount ratios). They will presume that higher-margin industries, such as investment banking, technology, or pharmaceuticals, will enjoy the luxury to maintain larger finance departments—and thus have lower headcount ratios.

This reasoning seems sound, but it doesn’t hold up sufficiently to be useful in practice. Breathtaking levels of variance can be found within the same industry. For example, Wall Street’s global-scale securities brokers tend to have the lowest headcount ratios of all, with a headcount ratio generally between 10 and 20. Their CFOs will explain that the nature of their business requires large finance departments for risk assessment, compliance, and performance reporting. And yet some in this industry will operate with ratios that hover in the 80s, a fourfold to eightfold difference. Regardless, none of these finance departments monitors its continuous operational risk.

At the other end of the continuum, the commodity-based industry of petroleum refining often has finance headcount ratios that exceed 200. Yet at least one global refiner maintains a relatively large finance group and has a headcount ratio of 15. Another refiner has a ratio of 75. These wide variances in a highly competitive industry can’t be explained by differences in technology, profitability, or business performance.

That’s why this metric, with its random data, is so valuable. It demonstrates that finance department operations aren’t obviously and directly linked to business performance currently. That bit of information is extremely valuable. It quantitatively illustrates the gaps in conventional wisdom for the size of finance department operations.

And what about the risk of these operations? If conventional wisdom can’t even predict the size of finance operations, how useful can it be for understanding the continuous risk that these operations might present to the enterprise?

By this point, CFOs can begin to capitalize on the wisdom in William Goldman’s observation about Hollywood: “Nobody knows anything.” Conventional wisdom is unhelpful, even counterproductive. It clouds CFOs’ understanding of the critical role of finance department operations. They fail to appreciate the value of lean finance department operations, and they fail to manage the continuous risks to the enterprise posed by inefficient finance department operations.

Yet these are easily fixed after conventional wisdom is discarded. CFOs can begin by implementing the next three performance metrics. On the bright side, the upside of improvement for their finance department operations is uncharted, and their competitive peers face the same challenging ambiguity.

CFOs can expect to be alone in this new “Hollywood” mind-set. Most finance group employees will struggle with the notion that their daily work routines produce losses. They won’t embrace measuring their productivity. Several arguments are most common. Knowledge workers will raise the topic of effectiveness but will offer few practical suggestions for its measurement or management. They’ll cite the consultative nature of their activities with the business units. They will cite the needs of their industry, insisting that different industries require more or fewer finance employees to support the needs of management. They will offer technology as a possible explanation.

The next three metrics can help these workers appreciate the true dysfunction of their work. They can help employees operate the department as a “measurement factory” for the enterprise. These metrics are designed to make the operation and its work products as tangible as possible.

This requires a major shift in thinking. Finance groups typically view their operations as services. They believe the business units are accountable for the accuracy and relevance of the management reports they request. All the finance department has to do is meet the specs and the deadline. To manage operational risk successfully, however, finance employees must accept accountability for the effects of the reports they produce. This includes everything from basic reconciliation and rework (direct losses) to distortions of operational performance (indirect losses).

METRIC 2: Unit Cost per Management Report

This metric, calculated monthly, is the cost of the management reporting employees (in the finance department) divided by the total number of recurring management reports they produce. No allocated costs, such as office costs, IT costs, or corporate overhead, should be included in this figure. The result will typically fall in the range of $2,500 to $7,500 per report. Yet the variability of individual reports is much greater. These can range from a low of $200 to as much as $80,000. These individual report costs are very useful for assessing the cost/benefits for the users in the business units.

Orienting the finance department to operate as a measurement factory requires that the outputs, or work products, of each different group within the department be defined. The inventory of work products must be standardized and managed.

This concept won’t be new to finance departments. The parts of the finance departments that answer to external authorities already operate as measurement factories. These external entities standardize the work products for all businesses. They also manage the inventory and ensure that it’s up to date. For example, the tax group’s work products are completed tax returns for payroll, income, and sales taxes. The CFO’s financial and regulatory reporting groups have similarly defined, widely recognized work products.

CFOs can bring similar discipline to the department’s unregulated, internally managed work products. Management reporting is the place to begin. Compile an inventory of existing management reports. Some IT systems keep track of this figure, but that information typically isn’t representative because the internal management reports, unlike the externally specified tax returns, have never been defined clearly.

As this inventory is developed, keep track of the report naming protocol (typically nonexistent). Identify the designated central repository for reports (again, likely nonexistent). Is there a directory or catalog of existing reports? This would make it easy for users to “shop” from the existing inventory rather than invent a new, one-off custom report that’s generated continually with no expiration date.

METRIC 3: Management Reports per Employee

This is the ratio (percentage) of total recurring management reports divided by the total number of employees. Again, the range of variation is breathtaking. One diversified industrial manufacturer with five divisions and more than 200,000 employees maintains tight control over its management reporting operation. It routinely produces 15,000 reports for a ratio of 8%. An international bank produces 30,000 reports for its 55,000 employees, resulting in a ratio of 55%. A global investment bank maintains a ratio of 110%.

Excessive management reporting is a widespread example of unmanaged finance department operational risk. The direct costs are substantial. The investment bank spent more than $200 million annually. Assuming that 80% of this cost is avoidable, the result is an internal “evaporation” of $160 million in earnings—a self-inflicted, direct, and measurable cost. At the company’s price-to-earnings ratio of 16, that depressed shareholder value by $2.6 billion—or 13% of total market value.

Despite the unrestrained proliferation of reports at the investment bank, managers were unable to pinpoint the sources of profitability. Less than 2% of the reports measured profitability, quality, or productivity. The resulting losses in overall business effectiveness are indirect and unmeasurable.

METRIC 4: Total General Ledger (G/L) Line Items

This metric is the number of active and inactive G/L items. Yet again, the variance seen in this metric is wider than most believe possible. The global investment bank cited in Metric 3 maintained 250,000 line items. The dividing line between active and inactive items was indistinct, undocumented, and consequently unmanageable. Internal managers in the finance department estimated that roughly half were active, but users were unaware of which were which. They could inadvertently use an inactive item.

By comparison, the diversified manufacturer cited in Metric 3 managed its G/L items as scrupulously as it did its finished goods inventory. About 5,000 core G/L items formed the foundation for 15,000 variations (subitems) to account for the needs of the five different divisions. The highly organized nature of these G/L items ensured that reconciliations were kept to a minimum.

ONLY THE FIRST STEP

Like the continuous risks they are meant to preempt, these four rudimentary operations metrics will seem alien to most CFOs. Some may scoff at their simplicity. But remember, “simple” doesn’t mean “easy.” Complexity is the enemy of effective finance department operations. These metrics are only the first, transformational step. They provide simple, clear fundamentals for managing the measurement factory—for moving past the “Nobody knows anything” stage.

These metrics will begin to transform the finance department into a “knowledge-work factory.” The CFO can then use the same approach to standardize operational reporting across the enterprise. Installing similar operations metrics in other business groups will help uncover the pervasive continuous risks that drain company earnings. With these risks identified and the standard reporting in place to monitor them, executive leadership can begin to manage these risks more effectively to mitigate both the direct and indirect losses that they generate.

October 2017