Pursuing our interest in internal controls, we started talking to current and former external auditors about six years ago. To our surprise, those external auditors seemed to have an aversion to the idea of controls, to testing the controls, and even to computer technology. We also talked to a Big 4 audit manager, who revealed his concerns about the time-consuming nature of testing his clients’ internal controls. He wanted to be able to rely more on the work internal auditors already do.

So we asked: Could automated internal control testing strategies help external auditors rely more on internal auditors? For example, let’s say internal auditors had failed to detect significant problems. Would the use of automated testing strategies improve external auditors’ trust in the internal auditors so they would rely on them more?

That’s an important question because companies can save money when external auditors rely more on internal auditors’ work—the external auditors will bill less for testing controls. We reviewed the academic literature, looking for answers. While we found some articles describing how to implement automated testing strategies, we didn’t find any research examining how useful or effective those systems are, especially for getting external auditors to rely more on internal auditors. Accordingly, we designed a study to find out.

Some of the increased importance of internal controls can be traced back to the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX), which came about following several high-profile accounting frauds and scandals. SOX Section 404 requires that management of large, publicly traded companies, such as accelerated filers, must take responsibility for establishing and maintaining adequate internal controls. Also, external auditors must evaluate and report on the effectiveness of internal controls over financial reporting. Although SOX requires that external auditors only identify material weaknesses in internal controls over financial reporting, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) requires an external auditor to notify, in writing, both the board and management of any material weaknesses or significant deficiencies. PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 2201, “An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That Is Integrated with An Audit of Financial Statements,” defines a significant deficiency as less severe than a material weakness but important enough to merit attention by those in charge of corporate governance.

When SOX was first being proposed and then implemented, one objection was the increased costs that these kinds of changes would add to audits. With external auditors being responsible for investigating and reporting on the effectiveness of internal controls within a company, it could require more work or time for the audit. We conducted an experimental study, sponsored by IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) and supported by a summer research grant from Hofstra University’s Frank G. Zarb School of Business, to understand how external auditors’ perceptions of and reliance on the internal auditors’ work change when the internal auditors fail to detect a significant deficiency in internal controls. (The full study was published as “The Effect of Frequency and Automation of Internal Control Testing on External Auditor Reliance on the Internal Audit Function” in the Journal of Information Systems, Spring 2016.) Relying on the internal audit function benefits all companies that engage external auditors because it can diminish redundancies in the work performed and thus reduce external audit fees.

THE INTERNAL AUDIT FUNCTION

In the post-SOX era, strong internal controls are beneficial to management because they help achieve objectives such as safeguarding assets, ensuring reliable financial reporting, maintaining compliance with regulatory requirements, and supporting operational efficiency. In fact, the New York Stock Exchange requires listed companies to have an internal audit function, which is composed of internal auditors responsible for evaluating and improving the effectiveness of internal controls, risk management, and governance processes.

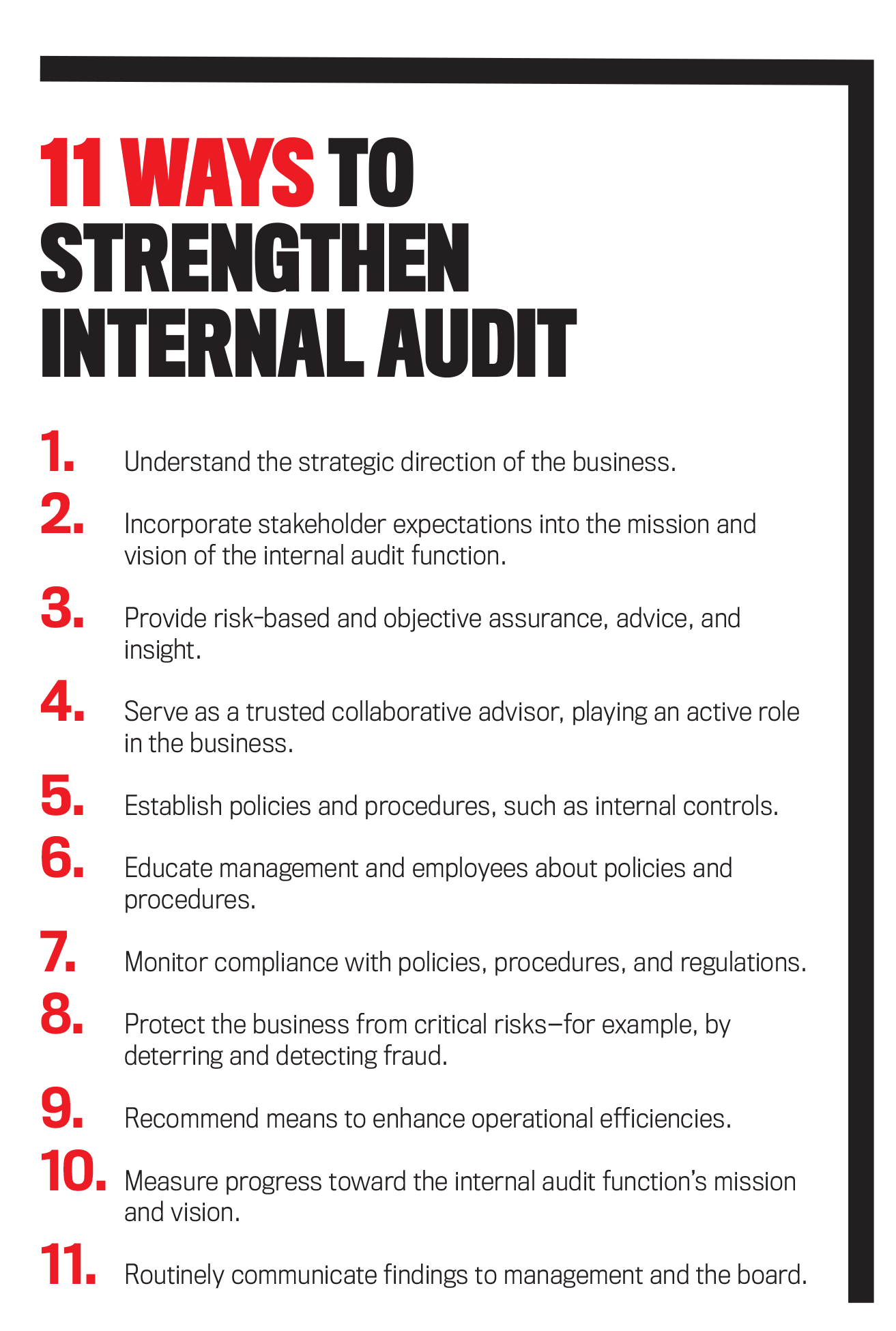

You can strengthen your company’s internal audit function. But like any other area of a company, a strong internal audit function requires an investment of resources. With any investment decision, management will ask, “Do the benefits outweigh the costs?” When it comes to the internal audit function, answering that question can be a challenge. Rapid advances in technology have resulted in new tools or software that can strengthen the internal audit function, but companies may be reluctant to make an investment because it’s difficult to say or quantify how investing in competent and objective internal auditors will benefit the company.

Ultimately, strong internal audit functions benefit companies in a variety of ways: by improving risk assessments, ensuring compliance with regulations, deterring and detecting fraud, and ensuring the proper functioning of internal controls. One significant advantage of a strong internal audit function is spelled out by the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA) in Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS) No. 128, “Using the Work of Internal Auditors.” It says that auditing standards permit the external auditor to rely on internal auditors as assistants or rely on the work performed by internal auditors who are sufficiently competent, objective, and perform quality work.

If management understands the importance of strong internal controls and how external auditors relying on the internal audit function can lower audit fees, they can implement internal control testing strategies using technology to detect, prevent, or remedy significant deficiencies in their internal controls. Once again, management must decide whether it’s worthwhile to implement internal control testing strategies by investing in new technology.

Do the benefits of implementing various internal control testing strategies outweigh the costs? We don’t purport to answer this question, but we can shed light on the differences in specific benefits for distinct internal control testing systems.

COMPUTERIZED INTERNAL CONTROL TESTING

Companies have various options for testing internal controls. In past years, management could test internal controls manually by physically examining documents. But today, the fast pace of technological innovation gives companies new problems to handle. With the advent of Big Data and the ability to collect massive quantities of data, companies have turned to computerized internal control testing options that don’t limit testing to particular samples. Two commonly employed computerized internal control testing systems are continuous controls monitoring (CCM) and Audit Command Language (ACL).

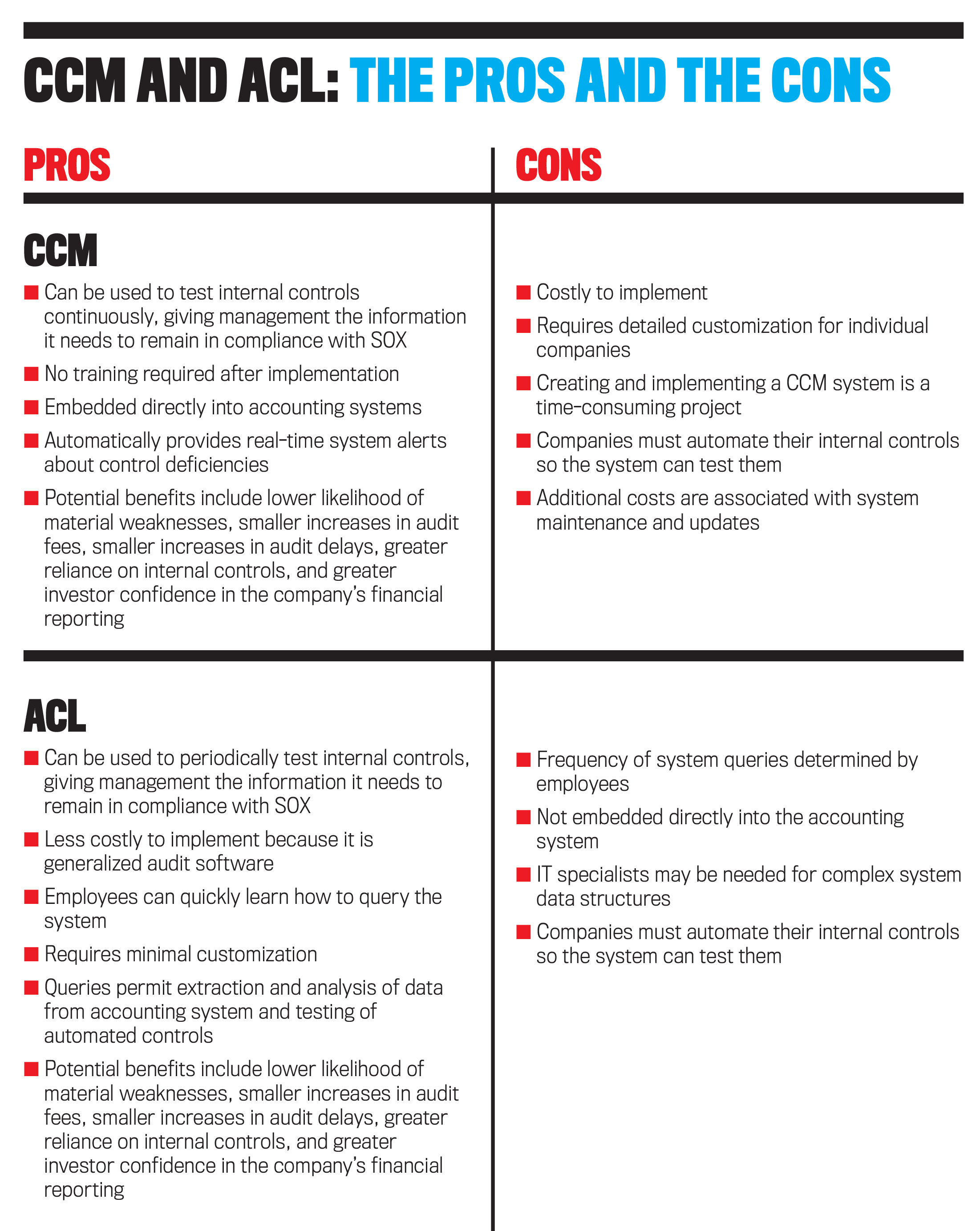

CCM systems are completely computerized in the sense that they are embedded audit modules in accounting information systems. CCM can detect deficiencies in internal controls on a real-time basis by sending message alerts to internal auditors, who can then inform management and the board about weaknesses in internal controls before they rise to the level of a material weakness. The drawbacks of CCM systems are the complexity and cost of implementing them into existing systems, the need to reconfigure CCM for system updates, the need for specialized personnel like information technology (IT) specialists, and CCM’s ability to only test automated controls.

ACL is a less expensive alternative to CCM because it’s a generalized audit software package that auditors can use to extract and analyze data, with internal audit personnel specifying the proper queries. Training to use ACL is relatively easy compared to CCM, and ACL requires only minimal customization. Like CCM, ACL performs automated testing that it can do more quickly and efficiently than manual testing can. Usually, internal auditors set up queries in ACL to test internal controls periodically as opposed to testing on a real-time basis. At times, implementing ACL also requires using IT specialists, such as when data structures are complex.

OUR STUDY

We recruited 141 external auditors with at least two years of audit experience to participate in an online experiment. The study examined external auditors’ reliance on the internal audit function. More specifically, we sought to understand how implementing different internal control testing strategies can improve the external auditor’s perceptions of internal auditor competence, work performance, and objectivity—as well as the external auditor’s reliance on the internal audit function. The computerized testing strategies included both CCM (automated, real-time control testing) and ACL (automated, weekly control testing). We also included a third testing strategy that consisted of manual, weekly control testing during which internal audit personnel conducted tests of controls.

Participants in our experiment were external auditors. Their average age was 33 years old, and they averaged seven years of external audit experience. Eighty-four percent of participants were CPAs, 20% were staff auditors, and 38% were managers or senior manager auditors.

The participants also had prior experience with computerized testing strategies: 59% reported prior exposure to CCM, and 60% said they had prior experience with ACL controls testing; 44% had been exposed to both CCM and ACL.

We gave study participants case materials that asked them to assume the role of an external auditor of a hypothetical company. Then we told participants that the internal auditors of the company had failed to detect a significant control deficiency during their tests of internal controls and that the participants’ team of external auditors detected that deficiency.

In the first stage of our experiment, the case materials said that the internal auditors had all appropriate qualifications and education for their job position and that they reported directly to the audit committee. Therefore, participants could infer that the internal auditors were competent and objective but performed poorly during their tests of internal controls. In the second stage of the experiment, the case materials described implementing one of the three remediation testing strategies—CCM, ACL, or weekly manual testing.

To capture the external auditors’ perceptions, we asked them to assess the quality of the internal audit function based on competence, work performance, and objectivity. Also, we asked our external auditor participants how much they would rely on the internal control testing the internal auditors performed.

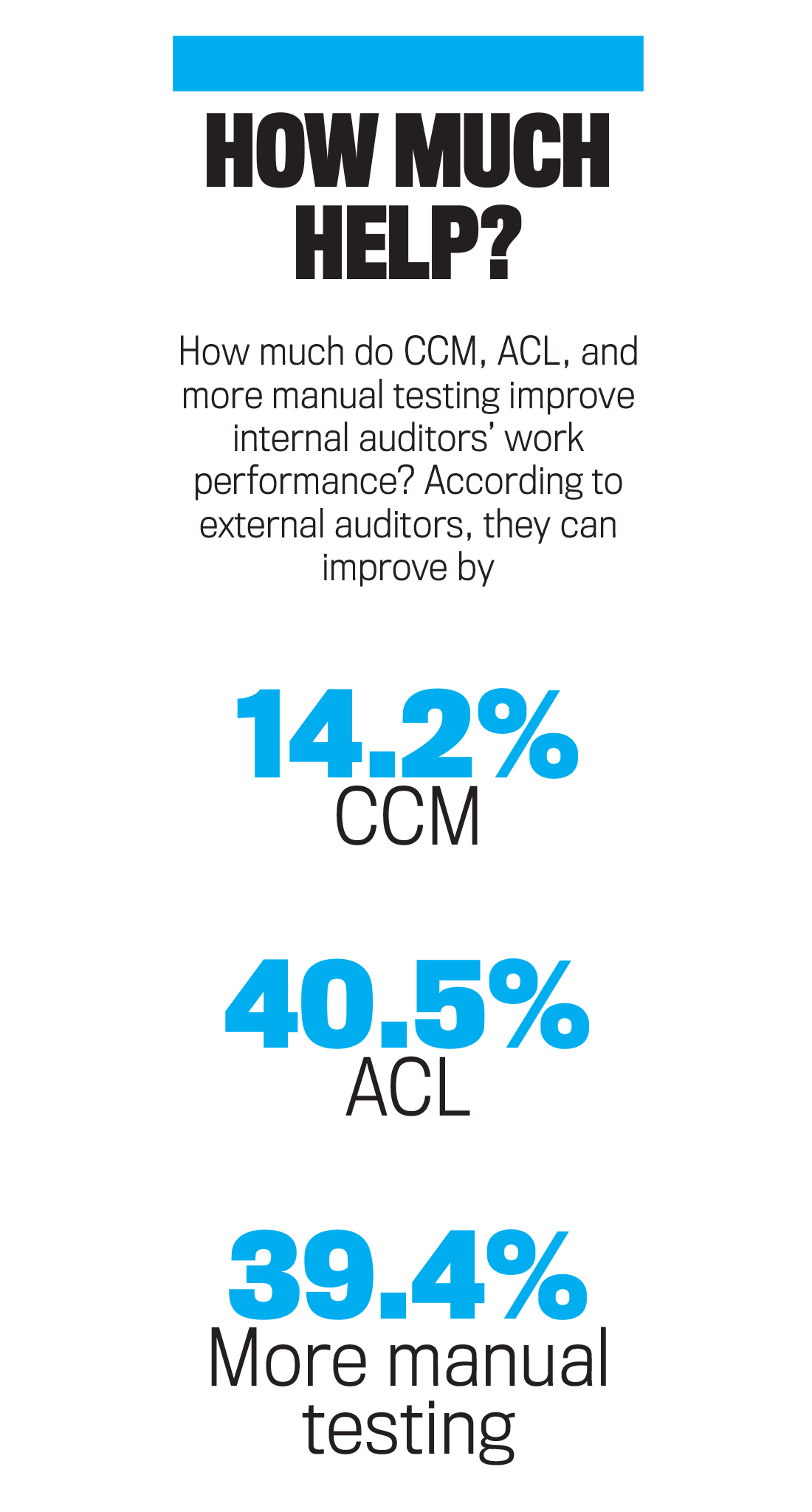

The external auditors assessed the internal auditors’ work performance to be of low quality when the case materials indicated that the internal auditors performed poorly during the tests of internal controls. While their perceptions of the internal auditors’ performance improved after we told them that the hypothetical company implemented some type of internal control testing strategy, perceptions improved more for ACL, which tests less frequently, than they did for CCM, which tests continuously.

Strangely enough, external auditors did appear to have a preference for computerized options that test less frequently. This preference not only influenced perceptions of the quality of work performance, but it also appeared to spill over into perceptions of the competence and objectivity of the internal audit function despite these two qualities being constant in the case materials.

We had expected that external auditors would perceive a continuously testing computerized system like CCM to be more reliable than a system that tests less frequently because continuous testing can provide management with real-time alerts of significant deficiencies in internal controls. After all, what could be better than round-the-clock testing? Why would external auditors perceive less frequent computerized testing as better than more frequent computerized testing?

We speculate that external auditors prefer periodic testing strategies because this requires the internal auditor to have more hands-on involvement, running queries periodically, than when a system automatically tests continually. Another possibility is that external auditors may subconsciously doubt that internal auditors can deal with the influx of flagged items generated from a CCM system that continually tests for deficiencies. Or perhaps more advanced technology is somewhat intimidating to external auditors, and they believe it would be even more intimidating to internal auditors.

While we can only speculate as to why external auditors seem to prefer less frequent computerized testing, both ACL and CCM computerized testing strategies lead to improved external auditor reliance on the work of internal auditors. And even though we found that external auditors rely more on internal auditors if they’re using ACL, a real-time system like CCM has many benefits for companies, and they must consider if the benefits outweigh the additional implementation costs.

We further examined external auditors’ perceptions of internal auditor competence and objectivity after they learned that the hypothetical company implemented one of three internal control testing strategies to remediate shortcomings in internal auditor work performance. Although the case materials throughout consistently described the internal auditors as competent and objective, perceptions of competence and objectivity were greater when the computerized control testing was ACL rather than CCM. The results of the study show that the frequency of the testing is more important to external auditors than who performs the testing—that is, whether it’s automated and done by computers or performed manually by people.

We expected that external auditors would increase reliance on internal auditors for both automated internal control testing strategies because CCM and ACL can test the entire population of company data, giving external auditors more confidence that any problems in the data would be found. Consistent with our expectation, external auditors increased their reliance on the internal audit function after management of the hypothetical company implemented either CCM or ACL. This finding is important because it demonstrates that there will be some benefit no matter which strategy management decides to employ.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

External auditors’ perceptions of the strength of the internal audit function affect their reliance decision, and external auditors reduce their reliance when they judge internal auditors’ work performance to be of low quality. External auditors improve their reliance on internal auditors more when a company implements a less frequent internal control testing strategy such as ACL compared to a more frequent testing strategy such as CCM.

Companies can clearly maximize the benefits of having a higher-quality internal audit function using either CCM or ACL. That action can also help companies save money from reduced audit fees to the extent that the external auditor increases reliance on the internal audit function. Companies will also have peripheral benefits: improved risk assessment, identification of fraud, and improved compliance with laws, regulations, and policies.

So the question becomes “Who should be performing the computerized internal control testing: internal auditors or external auditors?” The advantage of having internal auditors do it is that a company can be more responsive to issues that arise throughout the year. Waiting until the external auditor finds an issue is a reactive strategy, not a proactive one, and reactive strategies are inherently more costly.

Technological advancements and the shift to an interconnected, global economy have led to the proliferation of Big Data—data that’s so large and complex that it’s difficult for traditional data processing applications to process it. Because of Big Data’s significance in today’s world, companies are placing more focus on data analytics and ways of usefully interpreting the nuances that they can glean. We might argue that CCM or even ACL systems will be critical in this new era of constantly streaming data.

But to help ensure all companies’ data integrity, should standard setters mandate the use of systems that can test with much greater speed and efficiency than humans can? Or should management strategically decide whether implementing these technologies in their companies is beneficial? These questions remain unanswered, but they serve as food for thought in this quickly changing world.

This article is based on a study funded by the IMA® Research Foundation.

May 2017