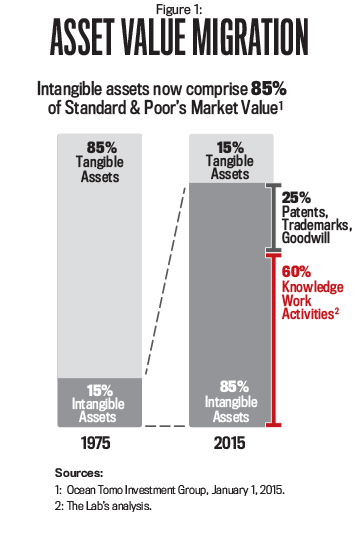

Standardization isn’t new. It enabled two centuries of industrial revolutions. But for nearly a century now, an anti-standardization bias has allowed basic opportunities for improvement in the office to hide in plain sight: the wasteful, one-off activities of white-collar, or knowledge, workers. That’s important because their work activities have grown to account for 60% of the market value of the average S&P 500 business. Now these inefficient activities are those companies’ most underproductive assets.

Shunning standardization forces knowledge workers to waste a third of their day performing easily avoidable, low-value activities, such as error correction, rework, and overservice. Ironically, these workers see these activities as helpful, even “virtuous.” Yet this “virtuous waste” squanders 20% of earnings. For the Fortune 500, this translates to shareholder loss of more than twice the combined market value of Apple, Google, and Microsoft. The additional losses that result from reduced business effectiveness are incalculable.

REPORTING’S COSTLY “VIRTUOUS WASTE”

You can get an excellent view of the anti-standardization dysfunction by reviewing the realm of management reporting, a breeding ground for the costliest virtuous waste in the business. Let’s take a look at one example.

The regional vice president of finance for a global telecom manufacturer beamed with pride as he said: “When I inherited this internal management reporting team, there were only three employees. Over the past seven years, we’ve grown it to a staff of 12.” The team had grown fourfold to accommodate an ever-increasing demand from business unit managers for more reports. The VP was happy to announce that no request had been turned away. “I can’t even tell you how many reports we generate, but it’s a lot!” Emergency, one-off requests from senior executives were always filled within hours. His finance team operated as a custom reporting service with no questions asked.

That was the problem. No one asked if the costly increase in management reporting improved business performance. It didn’t. During that seven-year period, revenue growth was consistent with historical averages. Operating margins as a percentage of revenue were virtually unchanged. Unit costs for finished goods showed a nominal decline. But the uncontrolled growth in management reports generated unseen, avoidable costs far beyond the expansion in the finance staff payroll.

For example, each report was designed individually to meet the requests of each user. The finance team never considered standardizing the reports because they never investigated how the reports were used. If they had, they would have learned that most of the differences in requests resulted from the users’ uncertainty about their reporting needs. They didn’t know what they needed and were too uncomfortable to ask the finance team for advice.

Other reports were intentionally self-serving, designed by users to game the system and report the results they wanted, e.g., to increase their annual performance bonus. The finance team focused only on fulfilling requests precisely and promptly. The result was a chaotic inventory of one-off reports that delivered inconsistent, unreconciled views of operations, products, and margins. Before senior business managers could hold a meeting, their analysts had to conduct a preparatory session to reconcile report data. The company managed its office furniture more rigorously than its management reports, which were the keys to its productivity and profits.

The VP’s objectives for expanding his reporting team were well intentioned, even “virtuous.” Yet the proliferation of nonstandardized reports generated hours of avoidable activity—waste—for the knowledge workers in the business. The reporting team’s operation was a high-growth “virtuous waste factory.” But no one saw that. It was just business as usual.

Preparing, deciphering, and reconciling a growing mass of reports represent only the direct, wasted labor cost of knowledge workers that resulted from the global telecom’s anti-standardization bias. The larger costs are indirect and incalculable: the decline in overall business effectiveness. Enterprise-wide, the explosion of one-off reports diminished rather than increased the visibility of business operations. Finance was obscuring the sources of profitability with its unfocused management reporting. Marketing was producing 25% fewer campaigns than its capacity allowed. And the plant schedulers failed to make full use of available production capacity.

All areas had their requested reports. Yet it was harder than ever to see precisely which business activities added value and which eroded it. There was one obvious exception. The expanded financial reporting teams, with their proliferation of one-off reports, clearly were eroding value.

This regional vice president, who was so proud of his growing staff, would soon report to a new CFO. As we’ll see later, that new CFO had a very different perception of management reporting.

STANDARDIZING: TAXES AND WRENCHES

What can companies do to rectify these situations? To claw back the value squandered by the anti-standardization bias, executives can begin by thinking of it as a self-imposed, internal “tax.” Without standardization, productivity is almost impossible to measure objectively. Subjective, qualitative measures are often substituted, such as “stoplight” charts that indicate status by color: green, yellow, red. Not surprisingly, this creates a predictable level of costly, avoidable knowledge work activity—a “tax” of wasted effort—that erodes the earnings of the business. Unlike government taxes, this internal one is never reported and never collected by the business. But it could be.

The CFO can collect this internal “tax” just as the U.S. government began doing when it introduced the federal income tax in 1913. It published a 14-page tax code that mandated universal standards for defining, measuring, and reporting business income—a form of standardized productivity management applicable to all businesses. Back then, accountants were stunned by the government’s mandate to standardize their knowledge work. They were accustomed to operating under financial accounting’s specialized knowledge and lack of documented standards.

Now, more than a century later, U.S. tax accounting is consistent and efficient wherever you go. But the lack of documented standards is still the norm for the most important accounting in the business: management reporting. These internal reports should help management see where value is created and lost. But for knowledge work organizations, most management reports merely track budgets.

The productivity of knowledge work is rarely measured. When it is, there usually are no consistent standards. CFOs can reverse this immediately. They can mandate a concise code to define, measure, and report the productivity of the knowledge work organizations in the business. This isn’t a new idea. In the last century, mandated standardization of knowledge work—think of industrial engineering—enabled the rise of manufacturing. But hardly anyone noticed that the standardization techniques applied to automobile engine assembly could be applied easily to the creation of a management report. It’s hard to notice and even harder to change.

Around 1915, as mass production of automobiles was emerging, progress was widely hindered by the anti-standardization bias among knowledge workers, predominantly engineers. On the plant floor, engineers specified a cumbersome, one-off array of wrench and bolt sizes until the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE International) mandated the sizes found in hardware stores today.

Upstairs in the office, design engineers were convinced that they needed more than 1,000 sizes of aluminum tubing to design cars effectively. But in one fell swoop, management mandated 50 standard sizes. Since then, great swaths of automotive engineering have been standardized and mandated into knowledge work factories. Think of plant scheduling.

MANDATING STANDARDIZATION

Now let’s revisit the global telecom company we looked at earlier. Its newly appointed CFO decided to act. The total number of employees in her finance organization was fast approaching that of the company’s outside sales force. The enterprise-wide cost of management reporting was inching higher than $300 million annually. Although she didn’t recognize it, she launched an improvement plan for management reporting that resembled the mandated standardization of the 1913 federal income tax code.

The CFO and a three-person special operations team created a standardization guide for management reports that mandated reorientation of the previous reports’ priorities from cost tracking to knowledge work productivity. For example, marketing efficiency was measured by the number of campaigns launched per person-hour. The effectiveness of each campaign was also tracked to ensure that volume gains didn’t compromise quality. Within six months, marketing discovered that achieving productivity gains also delivered more effective campaigns. Social media campaigns were reduced by roughly 20%, along with similar cuts in hard-copy catalog mailings. Response rates were unchanged. That’s because the reports were doing what they were supposed to do: show precisely where the marketing organization created and squandered value.

For the first time in the company’s history, a team created and analyzed an inventory of management reports. By reducing duplication and overlap, half the reports were eliminated within 60 days. The design of the remaining reports was engineered to accommodate standardized “plug and play” subassemblies, such as asset values and period costs. Nonstandard creation of subassemblies generated roughly half of all reconciliation efforts. Reports were stored in a central repository where a catalog for users described the purpose and characteristics of each.

The finance group also reduced the root causes of virtuous waste in its accounting operations. For example, they simplified the chart of accounts and installed a control process to limit the unrestrained creation of ledger line items and cost centers that contributed to unnecessary complexity and false precision. The most popular data was listed in the catalog and central repository, which the finance group made directly available to the businesses so they could perform “self-service” analysis and reporting. This enabled half of all remaining reports to be scheduled for retirement throughout the following year, which was a 75% overall reduction in reporting from the launch of the initiative.

ASSET VALUE MIGRATION

Almost everyone assumes that businesses operate rationally and productively. Rules are clear and simple. Waste is relentlessly reduced and eliminated. Operations are automated with the latest technology. Underproductive businesses and executives quickly adjust to the negative pressure from competitors and shareholders. The marketplace notices everything.

For generations this conventional perception represented reality. But then reality changed. In the 40-year period from 1975 through 2015, business value shifted dramatically (see Figure 1). The majority of business value moved out of the timeless, familiar neighborhood of tangible assets: property, plant, and equipment. It left the plant floor and moved into the offices where white-collar workers toil with their minds in areas such as finance, engineering, sales, and customer service.

Nothing prepared business to deal with this radical migration of value and work activity. Intangible assets are a relatively new development in the long arc of business history. Knowledge workers have always existed, but they were never so numerous or so valuable.

Previously, knowledge workers were charged with improving the productivity of tangible assets—the factories. They mandated standardization and succeeded wildly. During the past century, manufacturing worker productivity increased up to fiftyfold, delivering history’s greatest increase in economic wealth. But now productivity growth has slowed to a crawl. It’s time for knowledge workers to turn their skills inward, mandate standardization, and improve the productivity of their own work. They can do this by managing similar, repetitive activities just like factories do. Define the work products, streamline production, and carefully monitor unit cost, quality, and productivity. Let’s look at another example.

THE CFO: ENGINEER OF BUSINESS VALUE

Alain, the CFO of a global tire manufacturing company, was having lunch with Ted, the head of manufacturing for North American operations. They were discussing audits, and Ted was complaining about the time burden these audits imposed on his management team. “We have safety audits, financial audits, physical inventory audits, product design audits, and more. We never learn anything valuable from them. There’s hardly time to properly schedule the plant. We’re experiencing a ridiculous number of daily schedule changes.”

Alain spotted his opening. “How about you let my finance reporting team do an audit of scheduling operations? They can finish one plant in a week. I think you’ll get some interesting findings.”

Ted hesitated. His first instinct was to refuse, but he quickly reconsidered. After all, this was the corporate CFO. “Sure. I don’t know what my industrial engineers can learn from your accountants. Every plant is unique, which means every schedule is unique. But go ahead. I’ll make certain that my team cooperates fully.”

Alain grinned with satisfaction. He already knew the answer to this puzzle. More important, he was delighted that his team finally had secured a low-key opportunity to extend its knowledge work improvement capabilities to another continent within the company’s global footprint.

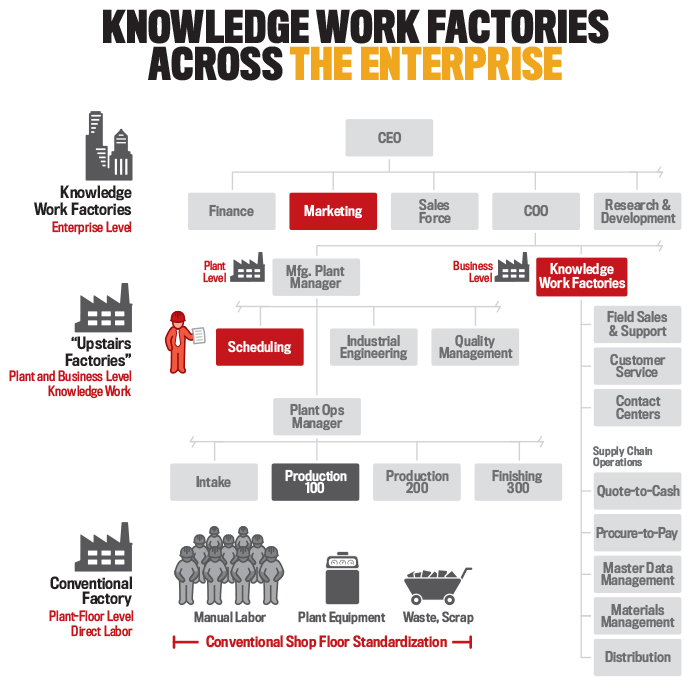

The reporting team consisted of a dozen traveling analysts attached to the CFO’s management reporting organization. They had spent the first six months of their existence standardizing the company’s internal reporting operations—creating a centralized knowledge work factory. Soon after, they began to scour the enterprise for other, high-value, nonstandardized knowledge work operations that could be similarly “industrialized.” They used the upgraded management reports to guide their search efforts. This led them to the marketing organization first and then to the customer contact center network. Now, two years later, they were tackling knowledge work within the plants. Fresh from their successful experience in Europe, they knew exactly what to improve in North America.

THE FACTORY RUNS THE PLANT

They began by defining the scheduling operation as a knowledge work factory that produced a “product”: a daily production schedule composed of roughly 100 subcomponents, or subschedules (for machine stations, material handling, even the power plant that generated steam and electricity). The industrial engineering team kept a database of rigorous scheduling standards. For every standard activity, the company had developed standard estimates of the time required to perform it. A critical path model considered the sequence of activities and made certain that irrational combinations couldn’t be planned into the schedules. This was detailed material. Typically, each activity was measured in increments of seconds or minutes and, just like each item in the material or supplies inventory, included a bar code number. This enabled digital scheduling, auditing, and tracking.

The reporting team members began their scheduling audit by focusing immediately on the manual edits to the digital schedule. They discovered extensive manual adjustments—always additions—to the scheduling standards that generated the estimated timelines. After generating a precise schedule based on standards measured to two decimal points, engineers routinely added single “override” line items that could extend production times by hours. These manual adjustments also understated the feasible plant capacity. The reporting team audit placed this shortfall at a conservative minimum of 12%.

The full-time plant scheduling team was small: seven engineers for a plant that employed more than 2,000 workers and operated 24/7 for all but one day of the year. Yet there was virtually no control over schedule revisions, so more than 100 plant foremen and team supervisors were able to modify their schedules. On average, the daily plant schedule was modified more than 2,000 times every 24 hours. The result: The plant schedule wasn’t a plan that guided activities but a record of after-the-fact activities. In a single afternoon, the CFO’s reporting team quantified the effect of this poor scheduling on the business and its shareholders.

Daily production routinely fell 15% below plan. Combined with the 12% shortfall from excessive manual adjustments, the plant was running 27% below feasible capacity. But there was full demand for its products, so this cost about $73 million annually in lost gross margin, which translated to $400 million in shareholder value at recent price-to-earnings ratios for the company. The finance team estimated that each of the 100 plant employees who routinely performed one-off adjustments to the schedule was costing shareholders and the business about $4 million annually in lost market value. The plant’s solution: Treat the schedule just like a product. Create an assembly line with quality checkpoints. Review the accuracy and reliability daily. Apply Lean improvement techniques to each identified “failure” and strive for a zero-defect schedule “product.”

SIMILAR OPPORTUNITY, DIFFERENT RISK

Despite an explosion of breakthrough technologies more than 100 years ago, the value of standardization wasn’t immediately obvious to the pioneers of mass production: gunsmiths, sewing machine makers, and automobile manufacturers. Their initial efforts were hobbled by nontechnology barriers: one-off wrenches, too many tube sizes, and the passionately held anti-standardization bias that viewed this undisciplined complexity as indispensable, even “virtuous.” Back then, management’s mandate to standardize the activities of armies of tradespeople toiling in factory workrooms was a risky, strategic gamble. But successful challengers of the anti-standardization bias often earned a huge payout.

Today, the rise of digital technology combined with the migration of asset value to knowledge work presents a perfect opportunity for nontechnology standardization. This time, management’s risk is reversed. Now, even hesitating to mandate standardization is the risky, strategic gamble because creating knowledge work factories is simpler and more affordable every day. And a rapidly expanding pool of viable, new digital adventurers, such as the predatory Fintechs (financial technology companies), is encircling established businesses. They seek the massive payout that comes from successfully challenging the anti-standardization bias. What will your company do to survive and thrive in this era?

How CFOs Can “Value Engineer” Knowledge Work

Knowledge workers’ wasteful, one-off activities erode 20% of business earnings. Their operations that are inefficient provide tempting targets for new digital disrupters. CFOs can help their companies break through this anti-standardization bias.

Mandate Standards for Management Reporting

Most finance organizations simply produce any report a business partner requests. But this well-intentioned strategy does the business a disservice. The reports create mountains of inconsistent data that require endless wrangling and reconciliation. More important, the reports make it impossible to see clearly where the business is creating value and where it’s losing value. CFOs can learn from the IRS. When the federal income tax was introduced in 1913, consistent reporting was implemented with only 14 pages of mandated standards.

Build the First “Knowledge Work Factory”

CFOs can lead by example in the effort to standardize knowledge work. In fact, a large portion of their finance organization is already standardized because of external regulatory guidelines for financial reporting, risk disclosure, and securities disclosures. And management accountants have standardized their own internal regulatory work and reports for years. Now it’s time to bring the same rigor and discipline to the way that internal management defines, manages, and reports the value created by the business.

Initiate Productivity-based Budgeting

Most finance organizations are accustomed to productivity-based budgeting and management for the organizations in their businesses that “move and make things.” It’s a simple change to adapt these same methods to the knowledge work organizations in the business. The challenge is to reorient knowledge work managers from focusing on expense line items (dollars) to work products (units). For example, a global retailer monitored its cost to process accounts payable from vendors. The total average cost appeared too low to improve: a few pennies each. That’s because machines processed most payables. When the human work activity associated with manual exception processing was isolated, it showed a different picture. The processing time for identical transactions could vary by a factor of seven or more. Inconsistencies in processing similar transactions created a host of costly liabilities and adjustments. These sometimes required adjustments to published earnings.

Redefine the Audit Function

Most audits are required by external parties to protect a company from losing value as a result of fraud, negligence, and numerous other risks. CFOs can take this thinking a step further. They can audit plant scheduling to ensure that casually inserted “fudge factors” don’t understate the capacity of the manufacturing network. And they can audit marketing campaigns to ensure that launch decisions generate an adequate return on investment.

Knowledge Work and Robots

Could you give your knowledge work to robots? Yes, if you were prepared.

Nearly half of existing knowledge work activities can be automated today with existing technology, but robotics has made little progress in the office. By comparison, the auto industry has been automating complex assembly activities with robots since the 1970s. Its secret: an industrial engineering process called design for machinability (DFM). This same process can enable robots to perform knowledge work, but the notion runs counter to everything some of us believe.

Robots and Self-driving Autos

To see how this might work, let’s look at an advance everyone is talking about: self-driving cars. Technology doesn’t yet exist to automate driving on a mass scale. No matter. The century-old DFM process is under way. Standards for automation already are being developed in tandem with the emerging self-driving technology as it advances.

For several years, many organizations have been developing standards to enable robots to drive cars. In 2014, SAE International published standardized taxonomies and definitions for self-driving cars. These include centralized libraries of self-driving information, technology connectivity protocols, safety standards, and anti-hacking guidelines. This isn’t very different from the standards for wrenches that SAE published to help facilitate the mass production of autos.

The goal of the DFM approach is to convert the skilled activities of drivers into “standards” that machines can perform now or after advances in technology.

Consequently, the automation milestones for robot-driven cars are forward looking:

2020 Self-driving cars are widely available from major automakers

2030 Uber predicts all its fleet drivers will be robots—not humans

2040 Engineering association IEEE predicts robots will drive 75% of all vehicles Robots and Knowledge Work

Now consider knowledge work technology. Roughly half of all knowledge work activities can be automated with today’s technology. But virtually no DFM process exists in knowledge work organizations. That means that necessary automation standards, common in manufacturing, are missing in knowledge work—and so are the robots.

Without standards for machines, taxonomies, definitions, and centralized libraries, robots will remain unable to perform knowledge work. As a consequence, knowledge work automation milestones simply look back and cite invention dates:

1960 Large businesses adopt mainframe computers

1980 Personal computers enter the workplace

2010 Mobile computing devices begin to influence knowledge work

In knowledge work, technology advances serve as upgrades to conventional tools: better spreadsheets, databases, search engines, and networks. This is like replacing a handsaw with an electric saw. Human discretion is still required to perform even the simplest, most repetitive knowledge work tasks. Design for machinability must come before shiny new machines. But very few activities in the office have been redesigned to make it easier for machines to take over the routine tasks.

Someday soon you may well ride to work in a robot-driven car. With office work automation stuck in the slow lane, though, you’ll probably still juggle emails, spreadsheets, and sticky notes, the quaint artifacts of pre-industrialized knowledge work.

The Emergence of Knowledge Work Factories

As early as 1920, management innovators demonstrated to business executives that white-collar, or knowledge, work operations could be simplified and standardized. Most are now forgotten, but W.H. Leffingwell and C.C. Parsons, known as office management engineers, were two of the most prominent. And L.W. Ellis identified operational improvements in a 1917 advertising operation that can still be found in the most sophisticated marketing groups today.

Without technology, all three created “knowledge work factories” that capitalized on the then-new ideas enabling mass production in manufacturing: standardization, simplification, and division of labor. They streamlined office workflow, standardized procedures, and simplified activities for workers and even customers. Free-form business processes were standardized into virtual, well-documented assembly lines. In such unlikely organizations as marketing and advertising, this delivered breakthrough gains in productivity and effectiveness.

But management rejected the idea of mandating standardization in office work because knowledge workers constituted an insignificant share of total employees and business value. Tangible assets were king. Increasing the productivity of property, plant, and equipment was the most valuable improvement available. Back then, the idea of knowledge work factories was too far ahead of its time. Now it’s too far behind.

June 2017