We found that data analysis, another important skill for those in accounting, finance, and auditing, is an ideal venue for practicing critical thinking. The two concepts are intertwined: Improving one will ostensibly improve the other, and vice versa. We have formulated a straightforward, practical definition of critical thinking and, using a case study, will illustrate this connected relationship. With that understanding, it should be easier for accounting, finance, and audit practitioners and students to improve their critical thinking skills.

WHAT IS CRITICAL THINKING?

We asked Jeff Thomson, president and CEO of IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants), why today’s accountants, financial managers, and auditors must have strong critical thinking skills. He said, “CFO teams have expanded their influence and accountability beyond value stewardship to include value creation, with increasing responsibility for strategy, operations, and technology. To step up to this challenge, all members of the CFO team must think critically about strategy and operations to effect smart decisions.”

But it’s tough to pin down what “critical thinking” really means. In The Wall Street Journal article, EY Americas Director of Recruiting Dan Black explained, “It’s one of those [terms]—like diversity was, like big data is—where everyone talks about it but there are 50 different ways to define it.” The article also noted, “Critical thinking may be similar to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous threshold for obscenity: You know it when you see it, says Jerry Houser, associate dean and director of career services at Willamette University in Salem, Ore.”

Given its importance, we believed a simple, concrete definition would form a basis for improving critical thinking. We studied published descriptions of critical thinking and asked selected finance, accounting, and audit experts to share their thoughts about the concept. From that research, we concluded that critical thinking must involve curiosity, creativity, skepticism, analysis, and logic. (See “Critical Thinking” for our full definition.)

This definition confirms that improving critical thinking skills is possible. There isn’t an aspect of it that is unobtainable. Although some people are innately more curious, creative, or skeptical than others, everyone can exercise these personal attributes to some degree. Likewise, while some people are naturally better analytical and logical thinkers, everyone can improve these skills through practice, education, and training.

Employers justifiably expect entry-level accounting, finance, and audit professionals to demonstrate strong critical thinking skills. University professors can help their students meet this expectation by challenging them to think critically in their coursework. One way to do this is to assign practical activities, such as real-world case studies, that rouse students’ curiosity, creativity, and skepticism—and compel the students to analyze evidence and formulate logical conclusions.

But critical thinking growth shouldn’t stop when someone graduates from college. Accountants, financial managers, and auditors must continue to develop their critical thinking proficiency throughout their careers. They should always look for opportunities in their day-to-day work and continuing professional education programs to apply curiosity, creativity, skepticism, analysis, and logic.

ANALYZING DATA HELPS CRITICAL THINKING

Due to its iterative nature, data analysis is an ideal setting for developing critical thinking. When we asked Melissa Frazier, a retired vice president for audit and controls for Comfort Systems USA, about this, she said, “Critical thinking is key through each step in the data analysis process. If you don’t do a good job on each step, your result will be flawed or useless.”

The relationship also is reciprocal: While analyzing data strengthens critical thinking, critical thinking in turn helps data analysis. Jeff Thomson explains, “Data analysis and critical thinking skills are interdependent. Data analysis requires you to think critically by probing, connecting disparate facts, synthesizing, etc. Likewise, critical thinking is enabled by the ability to think analytically and apply tools to help extract insights and actionable information from data.”

But how does critical thinking as we define it merge with diagnostic data analysis? We developed a case study (see “CASE STUDY: Fraudulent Financial Reporting” below) to demonstrate how elements of critical thinking are needed at each step in the data analysis process. The case centers on Emersyn Grace, who was hired to establish an internal audit function for ACJ Company, a wholesaler. As she familiarizes herself with the company’s operations, Emersyn discovers some issues of concern that require her to employ critical thinking skills while further analyzing the company data.

Although the case study takes place within an internal audit setting, all accounting, finance, and audit professionals should be able to proficiently perform data analysis procedures like those Emersyn completed. Likewise, Emersyn exhibits critical thinking skills that all accountants, financial managers, and auditors should strive to emulate.

THE DATA ANALYSIS PROCESS

Diagnostic data analysis involves a basic process that requires critical thinking:

- Identify data analysis opportunities,

- Specify the objectives of the analysis,

- Develop expectations and define anomalies,

- Analyze the data and investigate anomalies,

- Evaluate the results, and

- Formulate a remedial action plan.

Analyzing data through this process requires accountants, financial managers, and auditors to apply their curiosity, creativity, skepticism, analysis, and logic. Let’s look at each step in more detail and see how Emersyn applied critical thinking skills in her data analysis.

Identify Data Analysis Opportunities

Accountants, financial managers, and auditors routinely analyze data as part of their day-to-day responsibilities, but they also need to be alert for and recognize unusual, unanticipated analysis opportunities. Critical thinkers’ curiosity inspires them to watch for potential analysis applications; their creativity enables them to consider what they see from different perspectives; and their skepticism empowers them to sense when what they see just doesn’t seem quite right.

Emersyn’s curiosity about ACJ Company—her eagerness to learn—prompted her to analyze its financial statements. Her creativity motivated her to analyze ACJ’s financial position and performance not only from a company-wide perspective but also from a store-by-store perspective. Her skepticism regarding the abnormalities she uncovered in the aggregated account balance data prompted her to extend her analysis by drilling down into the underlying, disaggregated transaction data.

Specify the Objectives of the Analysis

After identifying the data analysis opportunity, critical thinkers must plan the analysis. That begins with specifying appropriate objectives. For routine, day-to-day analyses, this is rather straightforward. Specifying the objectives for unforeseen data analysis projects is often driven by skepticism and requires creativity. Critical thinkers instinctively focus their attention on unusual circumstances and events they observe. Then they consider the reasons why the abnormalities may have occurred from various perspectives and set out to investigate them. The causes of unfavorable irregularities in business performance include things like operating inefficiencies, noncompliance with applicable laws and regulations, and fraud.

The objective of Emersyn’s premeditated financial statement analysis was motivated by curiosity, not skepticism; she simply wanted to enhance her understanding of ACJ Company’s financial position and performance. Her skepticism kicked in when she uncovered unanticipated abnormalities in specific account balances. Not willing to accept what she had discovered at face value and needing to be convinced that her concerns were warranted, she creatively refocused the objective of her data analysis to assessing the integrity of the underlying transactions.

Develop Expectations and Define Anomalies

Next, critical thinkers must establish expectations of data analysis outcomes and define data abnormalities that signal potential problems, such as inefficient operations, noncompliance with applicable laws, or fraud. Developing expectations and defining anomalies require analysis and logic. Critical thinkers carefully study the environmental factors that could affect the data, such as current economic conditions; the financial well-being of the company; the effectiveness of internal controls; changes in procedures, personnel, or technology; and the performance of comparable business units. Based on this inquiry, they formulate rational expectations regarding the outcomes of the data analysis and identify plausible indicators of problems they may observe during the analysis.

Emersyn’s understanding of ACJ Company was insufficient for her to establish legitimate expectations heading into her preliminary financial statement analysis. But her store-by-store comparison revealed anomalies in the aggregated account balance data of one store, which compelled her to reexamine the facts of the situation and proceed accordingly. She determined that she needed to investigate the detected anomalies by analyzing the disaggregated transaction data underlying the account balances of that store. Based on her financial statement analysis findings, Emersyn logically expected her follow-up transaction analysis to uncover anomalies.

Analyze the Data and Investigate Anomalies

Data analysis obviously involves “analysis,” which, by definition, is a key component of critical thinking. Critical thinkers systematically gather and examine relevant evidence using appropriate procedures. Skepticism compels them to assess all evidence critically, whether it corroborates or contradicts their predetermined expectations. They continuously question what they see and hear and rigorously investigate new evidence coming to their attention, including any anomalies.

Emersyn analyzed aggregated account balance data using an array of interrelated data analysis procedures: common-size financial statement analysis, ratio analysis, trend analysis, and internal benchmarking (comparing the financial position and performance of individual stores). She appropriately ascertained that some of the evidence she gathered and examined—the anomalies pertaining to particular accounts—warranted follow-up analysis. Realizing that analyzing disaggregated transaction data would provide evidence regarding the correctness of the aggregated account balance data, Emersyn used data analysis software to test the validity of transaction amounts included in the account balances.

Evaluate the Results

Next, the diagnostic data analysis results need to be evaluated, which requires logic. Critical thinkers understand that they must reach well-founded conclusions by properly interpreting evidence that’s persuasive—that is, it must be relevant, reliable, and sufficient.

Emersyn appropriately determined that her financial statement analysis hadn’t yielded evidence that was sufficient, relevant, and reliable enough for her to reasonably ascertain whether specific account balances of one particular store were incorrect. But her follow-up transaction analysis produced persuasive evidence, and she logically concluded that certain balances were misstated. Nevertheless, Emersyn wisely determined that she still didn’t have convincing evidence that the misstatements were caused by fraud.

Formulate a Remedial Action Plan

The final step is to formulate a sensible remedial action plan to address detected anomalies, which requires analysis, logic, and creativity. Critical thinkers understand that effective solutions treat the sources and causes of problems, not the symptoms. After diagnosing where and why anomalies originate, they innovatively prescribe practical, cost-effective remedies.

After detecting and uncovering control deficiencies that created an opportunity for a store manager to commit fraud, Emersyn reasonably and resourcefully prescribed controls designed specifically to effectively and efficiently reduce the risk of future fraudulent financial reporting by store managers.

WHAT ARE YOUR NEXT STEPS?

Entry-level accounting, finance, and audit professionals are expected to be adept critical thinkers. Moreover, they must continue to develop their critical thinking proficiency over the course of their careers. Adopting a straightforward, practical definition of critical thinking, like the one proposed in this article, is a sensible first step.

An appropriate next step that practitioners and students can take, with assistance from their mentors and teachers, is to measure their critical thinking proficiency using simple questions. Then they can identify and proactively engage in activities conducive to critical thinking. In time, engaging in accounting, finance, and audit assignments that require curiosity, creativity, skepticism, analysis, and logic will culminate in improved overall professional and scholastic performance.

CASE STUDY: FRAUDULENT FINANCIAL REPORTING

ACJ Company, a growing, family-owned wholesaler of electrical lighting fixtures and ceiling fans, is headquartered in Kansas City, Mo., and has five stores, each in a separate Midwestern city. Andrew Franklin, the founder and CEO of ACJ, hired Emersyn Grace away from her audit position with a public accounting firm in January 2017 to establish an internal audit function.

Financial Statement Analysis

Emersyn wanted to acclimate herself to her new position as quickly as possible. Knowing that analyzing ACJ Company’s financial statements would give her valuable insights about its financial position and performance, she prepared common-size financial statements and calculated financial ratios for ACJ and each of its stores for 2016 and 2015. She compared the 2016 and 2015 financial position and performance for ACJ as a whole and for each store. She also compared each store’s 2016 financial position and performance with those of the other stores and the overall company. Emersyn was eager to learn about the company, and she had no reason to question its overall financial position and performance or that of any store. Nevertheless, she began her analysis with an appropriate “trust but verify” mind-set.

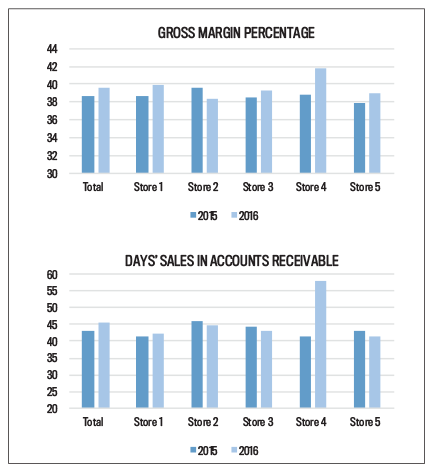

Emersyn’s financial statement analysis showed that ACJ had a strong balance sheet and that its sales and net income had increased nicely from 2015 to 2016, as had the sales and net income for each of its stores. Yet, as illustrated in the ratio charts below, her analysis also produced some peculiar ratios for Store 4. Its gross margin percentage and number of days’ sales in accounts receivable had increased significantly from 2015 to 2016 and were abnormally high for 2016 relative to the other stores and ACJ as a whole. These results piqued Emersyn’s curiosity. Why had Store 4 been proportionately more profitable? Why had it collected its accounts receivable more slowly?

Emersyn considered these questions. Increased credit sales to riskier customers might have caused the growth in sales and slowdown in collecting accounts receivable, but it wouldn’t have caused the higher gross margin percentage by itself. Overstated ending inventory and understated cost of sales might explain the higher gross margin percentage, but it wouldn’t explain the slowdown in cash collections. Moreover, Emersyn’s analysis hadn’t revealed anything amiss with inventory and cost of sales.

Why had Store 4’s profitability improved and its collections from customers worsened at the same time? With that question, Emersyn’s curiosity shifted to skepticism when she surmised that one answer might be fraudulent financial reporting—that is, the intentional recording of fictitious sales. Realizing that she needed to dig deeper to corroborate her suspicions, Emersyn decided to analyze Store 4’s 2016 sales transactions.

Analysis Of Sales Transactions

Emersyn knew that if Store 4’s manager had intentionally recorded fictitious credit sales, he most likely wouldn’t have recorded the corresponding cost of sales. She also knew that accounts receivable associated with fictitious credit sales would never be collected. Accordingly, she set out to determine whether the store’s sales and accounts receivable were overstated. More specifically, Emersyn:

- Asked an ACJ Company IT specialist to help her identify, locate, and access pertinent sales, accounts receivable, and inventory data stored in the company’s database system;

- Imported the electronic data obtained from the system into data analysis software;

- Verified the veracity of the data using predetermined control totals; and

- Examined the data to determine whether there were any recorded credit sales for which no matching charges to cost of sales and no subsequent customer payments existed.

Emersyn expected to find both types of anomalies, and her analysis corroborated those expectations. She uncovered sales transactions with no corresponding cost of sales and no subsequent customer payments.

Although the nature of the misstatements in Store 4’s accounting records pointed to fraud, Emersyn knew that she hadn’t yet obtained convincing evidence of intentional wrongdoing. She discussed her findings with Andrew, who agreed that they were highly suspicious. Andrew was especially sad because the manager of Store 4 was his nephew, whom he had hired for that role early in 2016. To entice his nephew to leave his management position at a large corporation and accept the challenge of improving the performance of Store 4, Andrew had offered him a performance-based commission.

Andrew met with his nephew, who was at first defiant but then confessed to recording fictitious sales. He had felt tremendous pressure to prove to his uncle that he could increase sales and profits. Moreover, a significant amount of personal debt had made the temptation to exploit his uncle’s generosity irresistible.

The Remedial Action Plan

Emersyn realized that her recommendations for corrective action needed to target the source and cause of the accounting misstatements she had uncovered. The immediate source and direct cause of the misstatements—Store 4’s manager and his fraudulent financial reporting—were obvious to Emersyn. She knew that firing the manager and eliminating the incentive to commit fraud were necessary to fix the problem and that, to some extent, these steps might deter future frauds of a similar nature. But she also knew that these actions didn’t constitute a viable long-term solution by themselves.

Emersyn set out to learn how the fraud had been perpetrated and gone undetected throughout the year. She found that there were no IT controls in place to prevent Store 4’s manager from recording credit sales without recording the corresponding cost of sales. She also learned that ACJ Company’s senior management team had done virtually nothing during the year to oversee the operations and monitor the performance of Store 4.

Accordingly, Emersyn focused her proposed remediation on rectifying these control deficiencies in a cost-effective manner. She recommended that controls be built into ACJ’s accounting information system to preclude store managers from accessing their stores’ accounting records without first obtaining direct authorization from ACJ senior management. She also proposed implementing a monthly reporting process that would enable Andrew and ACJ’s CFO to monitor each store’s performance throughout the year.

June 2017