The competition is named in memory of Carl Menconi, who held leadership positions in IMA for many years and served as chair of the IMA Committee on Ethics. The objective of the competition is to develop and distribute business ethics cases with specific application to management accounting and finance issues and that use the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice as a reference or guidance tool.

The winning case and teaching notes are available for use in a classroom or business setting. IMA academic members can access and download the teaching notes from the Academic Teaching Notes library via the IECJ section of IMA’s website: www.imanet.org/educators/ima-educational-case-journal.

Oliver Bloom’s hard work in Dex Corporation’s Leadership Development Program (LDP) had paid off. He was about to start his new position as accounting manager at Dex headquarters in Raleigh, N.C. Dex Corporation was started by two friends, Neha Kaur and James Murphy, in 2005. A few years later, they added a customized electronic device division, and the company’s sales grew exponentially. About seven years ago, Dex expanded internationally, opening two manufacturing plants in Ireland and a handful of sales offices around the world. Although the international expansion led to incredible growth, there were definitely new challenges that came with having multinational operations. Neha and James wanted a way to ensure that future department leaders and executives would be well acquainted with those challenges and the details of Dex’s international operations, so they launched the LDP four years ago. Promising staff from various company departments were selected to complete four one-year rotations, each in a different facility, with at least three rotations occurring outside the United States. After completing the program, LDP participants would come back to Dex headquarters and help oversee the entire company, armed with a better understanding of Dex’s individual parts.

Based on his outstanding work as an accounting staff member, Oliver had been chosen as the accounting department participant for the inaugural class of the LDP. Oliver had spent the past four years as follows:

Year 1: accounting senior staff in the Cork, Ireland, Dex manufacturing plant

Year 2: accounting senior staff in the Buenos Aires, Argentina, Dex sales office

Year 3: accounting manager in the Dublin, Ireland, Dex manufacturing plant

Year 4: accounting manager in the Sydney, Australia, Dex sales office

In each of these roles, Oliver had focused on that individual location. Now that he was back at Dex headquarters, he would be working on reports and financial statements for the entire Dex group, consolidating information from all of Dex’s locations and subsidiaries. This was a big step up in responsibility that Oliver hoped would prepare him to someday be Dex’s CFO.

Oliver’s first day on the new job started with a meeting with his new boss, Francisca Diaz, the Dex controller. Francisca’s assistant followed them into the office and placed a huge stack of documents on the desk. Francisca worked her way through the pile as she walked Oliver through the main responsibilities of his new job, including the quarterly process of getting information from Dex’s various departments and subsidiaries to consolidate into the overall company financial statements and tax filings. Oliver hurriedly scribbled notes as she spoke, but he knew he would have to take a closer look at the documents when he got back to his desk and dig into the details as he made his way through his first few weeks on the job. When their meeting was over, Francisca encouraged Oliver to come to her if he had any questions.

A week later, Oliver noticed something strange as he reviewed the documentation for the Irish factories’ transfer pricing. The amounts listed for labor and overhead in the Irish plants were much lower than what Oliver expected. Oliver opened some files that he had used to create a cost-volume-profit analysis while he was working at the plant in Dublin. The costs reflected on the transfer pricing document were up to 50% lower than the costs listed in his old files. After spending a few minutes going back and forth between the various documents, Oliver realized that the transfer pricing report covered the prior quarter and he hadn’t worked in Ireland for more than a year. He figured that the plant managers must have implemented cost-cutting measures after his rotation, although Oliver worried that anything that led to such a drastic drop in cost might also lead to a drop in product quality.

Francisca was away on vacation. Although she had urged Oliver to reach out if any issues came up in her absence, he didn’t want to bother her with anything that wasn’t urgent. Besides, Oliver thought, they already had a meeting on the calendar for next week to discuss his transition, so he flagged the papers, set them aside, and made a note on his list of questions for the meeting.

Oliver tried to put the whole thing out of his mind, but he kept wondering how the plant managers had lowered costs. During his time at each of the two Irish plants, he had worked closely with operations management, providing detailed reports and sitting in on meetings focused on cost cutting. Oliver had even offered a few of his own suggestions, although none of them were ever used. Oliver realized maybe he was a bit envious that he wasn’t the one who had come up with this clearly ingenious solution.

Finally, the day of the meeting rolled around, and Oliver headed to Francisca’s office. She asked if he had any items he wanted to discuss, and he immediately brought up the transfer pricing report.

Oliver: I was reviewing the documentation on the transfer pricing for the Irish manufacturing plants, and I noticed that the listed amounts for labor and overhead were much lower than anything I ever saw while I was working there. I know when those facilities first opened, costs turned out to be higher than management expected. While I was there, we worked hard to find a way to bring costs down—and we did, a little bit. We never figured out anything this effective. I’m happy to see they found a solution, but I was hoping you could share the details with me.

Francisca: I completely forgot that your time in the LDP included rotations in both Cork and Dublin. Of course you would be confused by that report after being so familiar with the numbers they use internally. Actually, the numbers on those transfer pricing documents aren’t the result of cost-cutting measures. They are related to some tax planning we have done. Jack Chu, our tax director, can explain this much better than I can, but I will give you an overview. As you mentioned before, costs in Ireland were much higher than we expected, meaning that our profits, particularly the profits for our Irish subsidiaries, were much lower than expected. A few years ago when Jack and I were meeting to discuss how the international expansion was affecting the company financially, he explained that Ireland has a lower corporate income tax rate than most of the other countries where we operate. Therefore, it would be advantageous if we could move more of the company’s profit over to Ireland. So we decided to shift some costs from Ireland to other countries to increase our profit in Ireland. These numbers won’t be exact, but I can give you a basic idea of what we have done.

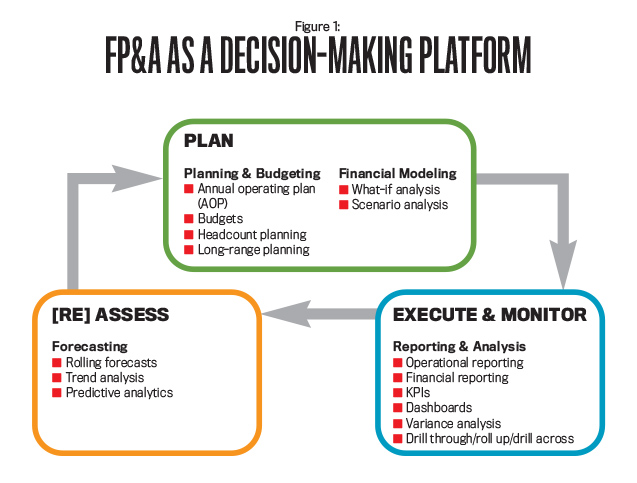

Francisca then drew a diagram on a board in her office (see Figure 1).

Francisca: As you know from your time in Ireland, circuit boards and processors are manufactured at the Cork facility. Those circuit boards and processors are then sold to the Dublin facility, where we finish production of our tablets, laptops, and other devices. The final products are then sold from the Dublin facility to our various sales entities around the world, including Sydney. The Cork facility, the Dublin facility, and the Sydney office are each in a different legal entity, so we have to keep track of those sales. Part of the reason Dex originally built the plants in Ireland is that we expected to see major savings on labor and overhead. Unfortunately, as we both know, things didn’t work out that way. That meant the majority of our profit was landing in our sales offices—for example, $300 in Sydney for every $50 in Cork and every $150 in Dublin. The fact that Australia, or really any of our sales office countries, has a higher corporate income tax rate than Ireland does just makes the whole situation worse. Jack and I had several conversations with our Irish managers, but, as you said, it seemed impossible to bring those costs down. Finally, Jack and I decided he would adjust the numbers slightly for tax purposes.

Francisca drew a second diagram below the first one on the board (see Figure 2).

Francisca: See, now more of the profit is in Ireland, where it’s taxed at a lower rate. All we did was take some of the labor and overhead costs from the Irish plants and shift them to the sales offices. That leads to a better after-tax profit for Dex as a whole. It really isn’t a big deal because, as you can see, we are properly reporting our total costs for parts, labor, and overhead. Even the total amount of profit is the same. We’re just shifting it to get more favorable tax treatment. If we didn’t shift those costs, more than half of the profit would be taxed at higher rates. Now the vast majority of our profits is taxed at the lower Irish rates. That obviously saves us a great deal of cash on taxes.

Although Oliver tried to hide it, his unease was written all over his face. Francisca could see Oliver wasn’t completely convinced, so she continued.

Francisca: This is good news for you! As you know, annual bonuses for those of us at headquarters are based on the after-tax profit of the company. The lower Dex’s taxes are, the higher our bonuses will be. Jack finalizes the tax returns for the entire company, even our international subsidiaries, so the adjustments he and I make to the numbers don’t affect anybody else’s work. Honestly, you really shouldn’t worry about it because none of this affects the consolidated reports and statements you’ll be working on other than the fact that our tax expense will be lower.

Oliver wasn’t a tax expert, but he was certain that you weren’t allowed to just shift numbers across tax returns without actually shifting the costs themselves in some way. The whole issue left Oliver feeling uncomfortable, but he certainly didn’t want to get on his new boss’s bad side, so he dropped it.

A few weeks have passed since this conversation. Oliver isn’t technically putting any false numbers in the reports and financial statements he prepares, but the issue continues to plague him. Oliver knows that Neha and James created that bonus structure thinking it would encourage everyone to work hard to grow Dex. He wondered if maybe they didn’t realize that it could also have a downside. Oliver is unsure of what to do and whether he has any responsibility to act. He wishes he could talk to someone about this. He still keeps in touch with some of his accounting professors, and he has friends from school who work in similar positions at other companies. In fact, most of them had recently congratulated him on his new position.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

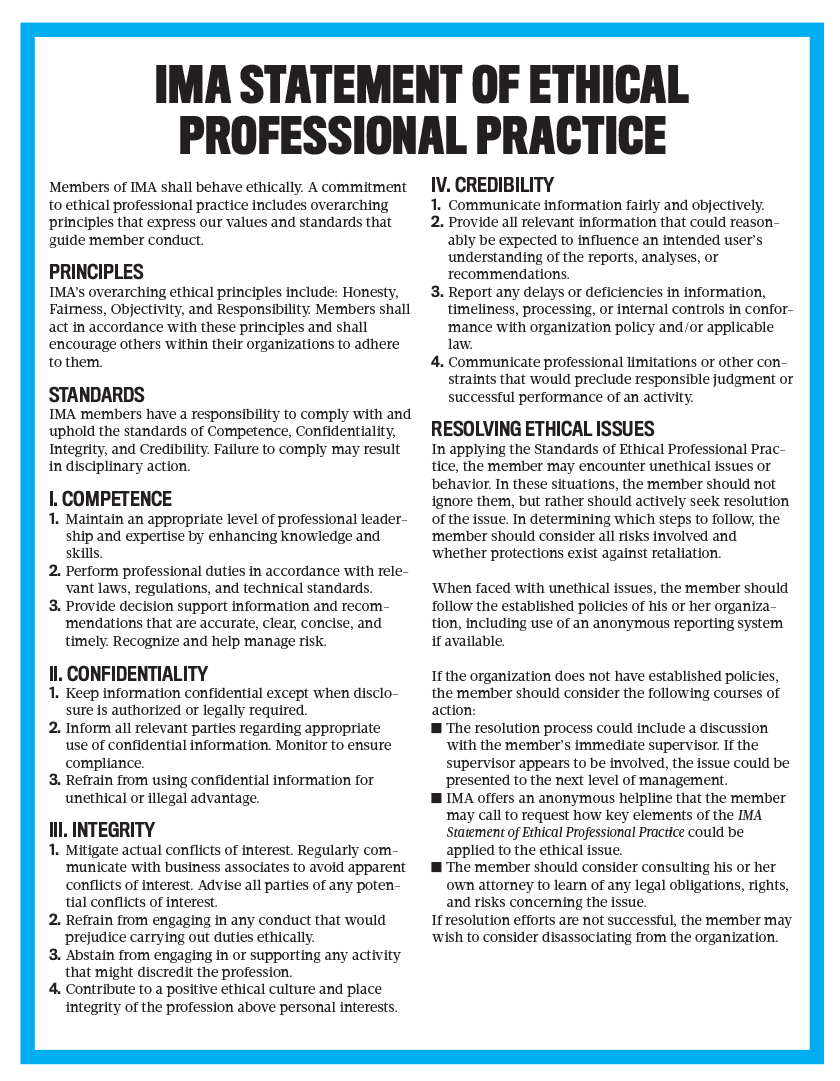

- What standards in the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice are particularly relevant to Oliver’s situation?

- Can Oliver discuss the situation with a former professor or classmate? Why or why not? If not a former professor or classmate, is there someone else Oliver can talk to about this?

- What do you think about Francisca’s statement that Oliver doesn’t have to worry about the numbers in the transfer pricing documents since he won’t be the one preparing the tax returns?

- The “Integrity” section of the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice states that members have a responsibility to “[a]bstain from engaging in or supporting any activity that might discredit the profession.” If Oliver fails to report the situation, is he “supporting activity that might discredit the profession”?

- Oliver thinks the bonus structure might incentivize employees to engage in dishonest behavior. Is there a way that the bonus could be structured to avoid this problem while still incentivizing employees to help the company grow?

- What options does Oliver have?

- What would you do if you were Oliver? Use the “Resolving Ethical Issues” section of the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice to map out the steps Oliver should take.

Note: As with all submissions to this year’s competition, this case was written using the previous version of the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice. Minor changes were made in questions 4 and 7 so that it now applies to the current Statement that became effective on July 1, 2017. See below:

July 2017