Now imagine the same coaches updating their forecast based on actual win-loss results during the season, conducting weekly variance analyses to see if their projection was accurate and what assumptions they made that turned out to be wrong: “We would have won, but number 47 on offense had only 40 yards rushing while we forecasted he’d have 70.” If you were a fan of the team, you’d start to wonder why the coaches didn’t instead spend that time developing a playbook and practicing—you know, the stuff that wins games. Yet this happens in businesses every day when forecasting overshadows or even replaces business planning.

Part of the problem is that the terms are often used interchangeably. But they are different. Planning is about knowing where you are today, determining where you want to go, and building a plan of action to get there. It fits the very definition of being proactive. Forecasting, on the other hand, is a crystal ball exercise. It’s about estimating what the future might bring. This isn’t to disparage forecasting. Both have their place and add value. Yet while many companies say they do planning, if you followed them around as they went through their processes, you’d have to conclude they’re actually doing very little planning and a lot of forecasting.

PLANNING OR FORECASTING?

Take a look at the most common “planning” process—the development of the annual plan. It goes by many names, such as the annual operating plan (AOP), the budget, or simply “the plan,” and usually involves a look at the anticipated balance of year results and the full 12 months of the following year.

In the typical process, the CEO and senior executives establish a financial target. This target almost certainly involves revenue but often targets for profit or EBITA (earnings before interest, taxes, and amortization) as well. Depending on the size of the company, targets will also be set for business units, geographies, product lines, and so forth.

Financial analysts have spreadsheet models that will take assumptions and translate them into financial projections. These models can be used to “back into” a number—in other words, users can keep adjusting the assumptions in the model just to get the desired answer. The simplest example of this is a revenue model built on assumptions for units sold and price. The analyst adjusts either input, or both, to produce a revenue projection. If the corporate management team has handed down a revenue target of 5% growth, the analyst can keep adjusting the price and unit assumptions to get there. Easy enough.

Of course, the Sales and Marketing departments might not want to sign up for a 5% growth target, so they’ll work with Finance to adjust price and volume assumptions to get to a number they feel more comfortable with, such as 3% revenue growth. If they’re smart, they’ll build some rationale along the way, for example, by arguing that increased price competition lowers the ability to raise prices or that stagnant market growth calls for capping volume assumptions.

The example here is a simple one focused on one line in the profit and loss (P&L) statement and using just a couple of input variables. You know these models get much more complicated. For each line in the income statement, there’s a model with its own set of inputs and calculations. Travel, salaries, advertising and promotion, trade discounts, overtime, raw materials, and more all have to be addressed.

In many companies, this is the typical annual planning process. Management hands down targets, Finance runs financial models to see what assumptions are needed to achieve them, and operational managers negotiate lower expectations to update those models.

What does any of this have to do with actually running a business? Nothing. And that’s exactly what frustrates people about the process and why nonfinance managers see so little value in the “planning” process.

It’s also the reason why flavor-of-the-month approaches to “better planning” never seem to pan out. They focus on how frequently forecasts are produced, or at what level of detail, or whether “budgeting” is needed at all. But they don’t get to the heart of the matter, which is that forecasting has all but replaced planning. And forecasting, though important, is not a substitute for business planning.

TRUE BUSINESS PLANNING

While forecasting focuses on “what if,” business planning focuses on “how to.” While what-if questions are always interesting, an organization’s success ultimately is driven by how effectively it can answer the how-to question.

Consider a hypothetical example where XYZ Company has a revenue growth goal of 8%. Rather than debating whether it instead should be 7% or 6%, the company would be much better off focusing on how the 8% goal will be achieved.

When talking about how an organization will achieve a goal like an 8% growth target, it isn’t about looking for superficial answers. For too many organizations, a conclusion such as “We’ll launch a new marketing program” seems to suffice. In the best-run companies, however, the planning discussions dive deeper. They’ll cover the components of that new marketing program, the timetable for rolling out each component, who the key employees are and their responsibilities in delivering the plan, and the type of resources required. The point is that the business planning conversation focuses on how the goal will be met, with senior executives challenging assumptions and testing the thinking behind the plan. If the process is done well, the result is a well-honed plan of action to drive success.

Going back to the football analogy, too many companies get caught up in the process of debating if their projected win-loss ratio should be 7-9 or lowered to 5-11. What they should do is identify what they need to do to win and then develop a playbook to do it. And here’s an interesting point: If the organization puts real thought and effort into how the goal will be achieved, then even a subsequent discussion about whether the target should be changed will be that much better informed and productive. Why? Because at that point senior management is evaluating a real action plan, and the conversation will center on what can be expected by executing those plans successfully. That’s why it’s important to develop well-informed, high-level targets and direct the organization to develop plans to meet them rather than spending that time debating targets.

IMPROVE VARIANCE ANALYSIS

One benefit of business planning over forecasting is it’s more likely the organization’s goals will be achieved. Additionally, when the year starts and the actuals begin to roll in, variance analysis goes from being superficial to being substantive. Without a real business plan, the Finance team can only say, “We have a negative 2% variance in revenue because we didn’t sell as much as we forecasted.” There’s very little business insight offered in that case—nothing that points to what can be done differently next time, nothing to learn from.

Contrast that with what you can glean from a real business planning process because there was a real, substantive plan. For example, if XYZ Company doesn’t grow revenue by 8%, the organization can identify what happened from a business perspective, like if a key marketing campaign launch date had been delayed or a Groupon event didn’t draw the anticipated response rate. Then it can delve much deeper into those issues. What caused the delay in the marketing campaign? If it was an issue with the advertising agency, maybe a new one is needed. If the root cause was that the marketing person leading the campaign left the company on short notice, maybe there’s an issue with succession planning. The analysis can reveal real business issues from which the company can draw important lessons and insights and learn what to do differently next time. In other words, it facilitates continuous improvement in the enterprise.

It may seem at this point that I’ve disparaged forecasting, but it does have an important role to play. After the business plan has been approved and the year begins, management needs a reality check. It needs an objective view on whether the organization is on track to achieve its goals or not. If it isn’t on track, then management can consider alternatives to achieving its goals. The forecast serves as an early warning system to give as much time as possible to readjust and get back on track.

THE WAY FORWARD

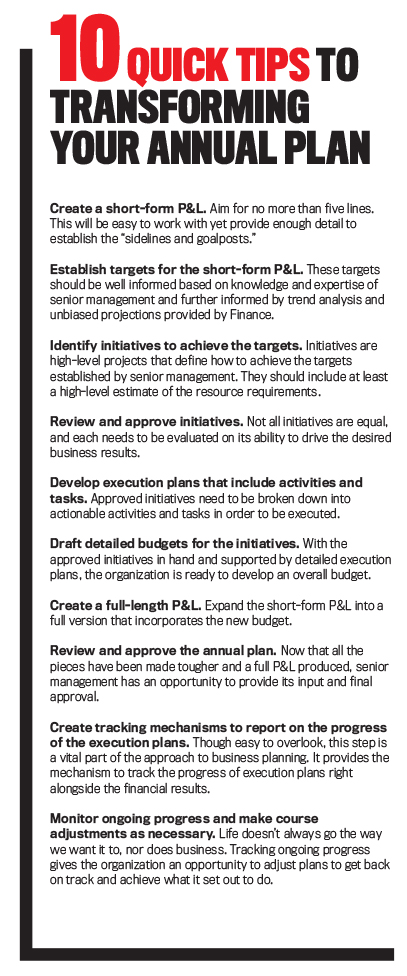

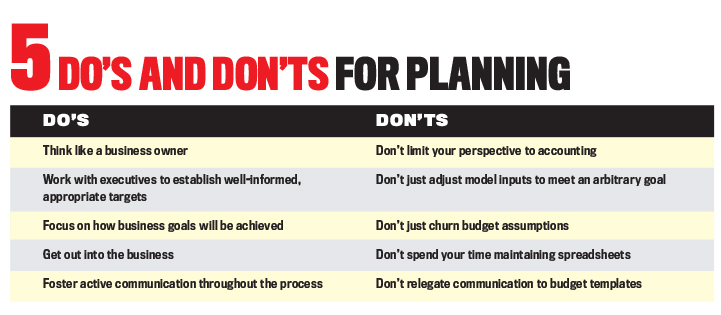

It’s important to ensure that your company is doing proper planning rather than creating forecasts and calling it planning. As stated, it begins by having senior executives establish well-informed, high-level targets (for example, revenue, gross margin percentage, EBITA). Finance has a critical role to play in presenting trend analysis, unbiased projections based on current reality, and other analysis to help executives make informed decisions. That process can kick off with an offsite meeting with the executives and should be concluded in a couple of weeks. Remember, this is their business, which they’re living and breathing every day. They probably have a good answer in their minds before the question is even asked.

The traditional process at this point would involve managers creating rationales for why the targets can’t be met and producing detailed P&Ls and other financial schedules that reflect reduced expectations. So here’s the big break with the traditional approach. Rather than develop a full-blown P&L and start an endless cycle of negotiations and managing expectations, challenge the organization to come up with a set of initiatives—along with high-level resource requirements—to meet the targets. Give the organization two to four weeks to accomplish that and present to senior management. Depending on the size and complexity of the organization, the review by senior executives could take a day or a week.

Coming out of that meeting would be a list of approved initiatives, which then should be further detailed in execution plans at the activity and task level. Resource requirements would be refined, and then a full P&L can be created. Notice that the focus of the process has shifted from endless rounds of forecasting and negotiating to a more pointed dialog about how to achieve the targets.

Will this put an end to gamesmanship? Probably not—at least not entirely. But those trying to game the process will be much easier to spot. They’ll be the ones marching in with superficial initiatives lacking depth and substance while carrying a long list of reasons why they can’t meet their goals. Over time, they, too, will learn it’s in their best interest to focus their attention on how to rather than why not.

The last step is to incorporate the initiatives and execution plans into the budget and produce the plan’s P&L. As long as the high-level targets (like revenue, gross margin percentage, EBITA) remain consistent, there can be flexibility in the individual line items of the P&L. If something truly game changing is revealed in the process of developing or reviewing the initiatives, then modifying a specific target may be warranted. But if that’s the case, modifying the target will be the result of a well-informed business process rather than the consequence of horse trading.

A quick note to supporters of rolling forecasts: As I noted, forecasting still serves a vital function as an early warning system and an unbiased view of the future state of the business. Forecasts should be completed on a monthly or an as-needed basis, but they shouldn’t be focused exclusively on the financials. They also should focus on the progress of the initiatives and execution plans that are designed to drive the financial results. If the plans are falling behind, then the expected financial results may also be delayed. Because this type of analysis requires an understanding of the business and the initiatives, which goes above and beyond the understanding of financial models, financial analysts might need additional training and development.

BACK TO YOU, COACH

A wise sage once said, “A problem well stated is a problem half-solved.” That simply means that we too often solve for the wrong problem. And until we define the problem properly, the answer will continue to elude us. The reason why coaches don’t go around projecting their win-loss ratio in the upcoming season is that it doesn’t solve their real challenge. Their problem isn’t how to do a better job projecting wins and losses, it’s figuring out how they’re going to win.

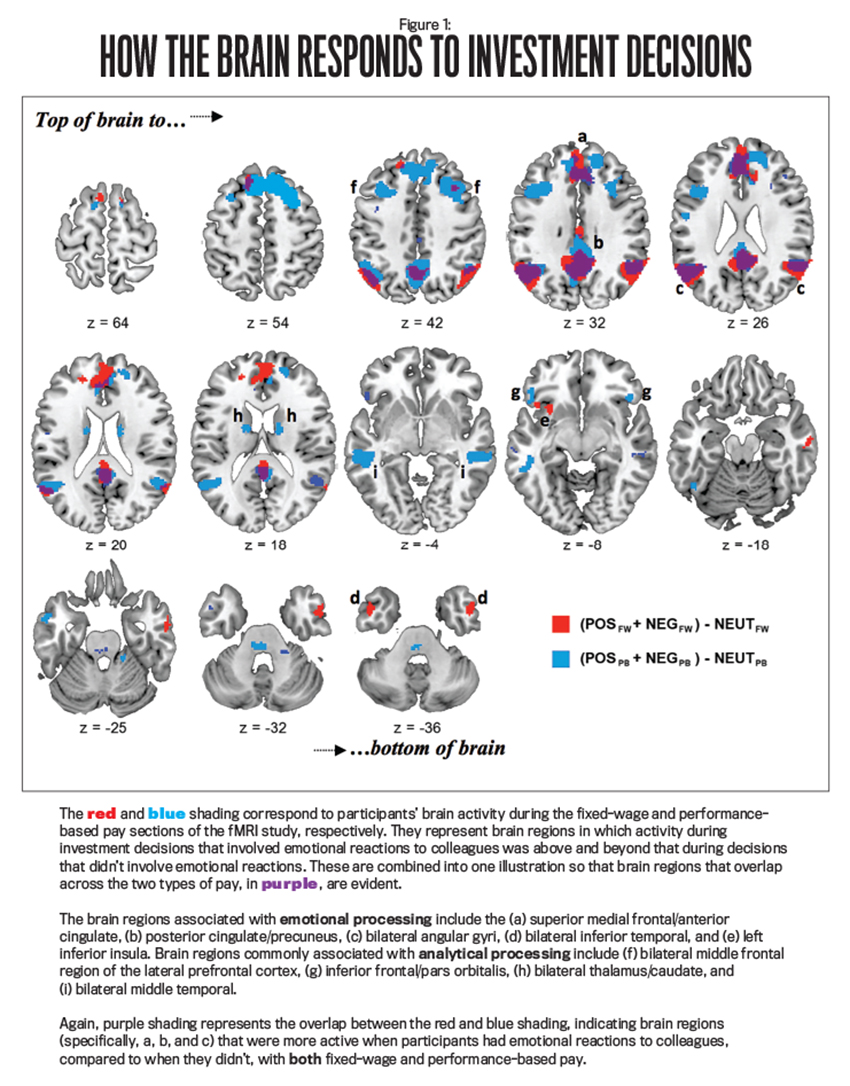

The same applies in business. Not to overlook forecasting’s importance, but the bigger challenge is how to make the future you want actually happen. The answer is in planning to win. That means revising the focus of the planning process. As Figure 1 shows, change the time spent on negotiating targets to instead focus on developing execution plans. Following this rigorous, more comprehensive approach to planning will result in actionable plans that truly drive business results.

SIDEBAR: THE DEATH SPIRAL

A very common refrain heard in business is “Our planning process takes too long and delivers too little value.” And the response to it is equally common. Addressing the “too little value” criticism seems a bit daunting, so most Finance teams focus on the “takes too long” aspect. And by “takes too long,” people outside Finance really mean “It takes too much of my time when I could be busy doing something that actually adds value.” So Finance looks to minimize the time required for people to engage in the process.

On some level, the fix seems straightforward. Since Finance owns the financial models that produce the projections, it will look to automate as much of the projection process as possible: Take a handful of input assumptions, apply some robust formulas, and deliver a new projection.

As easy as that approach sounds, those not in Finance often respond with a refrain of “That isn’t my number!” They see the projections as guesswork, detached from reality, and delivering no business value. This makes them less interested or willing to engage in the process.

As the resistance to engaging in the process grows, Finance looks for ways to minimize the time it has to “bother people.” This involves turning to the financial model and finding ways to further automate projections by refining or elaborating the calculations, changing or further minimizing the inputs (i.e., drivers). The result is a paper projection that reflects an even wider gap between the actual business operations and the business planning process.

This trap of minimizing the engagement of nonfinance managers, reducing the efficacy of the planning process, increasing the frustration with the results and lack of value, and then turning once again to refining financial models results in a death spiral.

If a process delivers zero value, then any time spent on it will be perceived to be wasted.

The answer is, yes, minimize any friction or inefficiencies in the process, but an overriding priority has to be improving the value that the process delivers; otherwise, no amount of process efficiency improvement will ever change the perception that the planning process takes too long and delivers too little value.

July 2017