Two things need to happen to make these choices effectively: Employees need to understand the cause-and-effect linkages between their choices today and better organizational performance tomorrow, and they need to be motivated to make choices consistent with that understanding. Companies already have tools that can help make these happen, such as goal communication and incentives, but the tools need to be used effectively. That’s easier said than done. First, it’s difficult for managers to identify which performance measures can help employees understand cause-and-effect linkages. Second, managers need to know whether simply providing those measures to employees is enough to motivate them to make decisions that benefit the firm in the long term or whether the measures should be linked to employees’ compensation.

Since the mid-1990s, organizations have been encouraged to identify the performance measures thought to be leading indicators of future performance for important strategic objectives. Thus, changes in a forward-looking performance measure today are associated with changes in important measures of organizational performance tomorrow. Companies can identify measures that capture these lead-lag relationships using either the experiences, beliefs, and intuitions of top management or statistical techniques such as regression analysis.

The challenges are in how to use such measures to effectively help employees understand cause-and-effect linkages and how to motivate employees to take actions accordingly. Furthermore, staff may respond differently to such cues based on whether they view themselves as short-term vs. long-term employees. As we’ll see, research has begun to provide food for thought on these challenges.

TYPES OF PERFORMANCE MEASURES

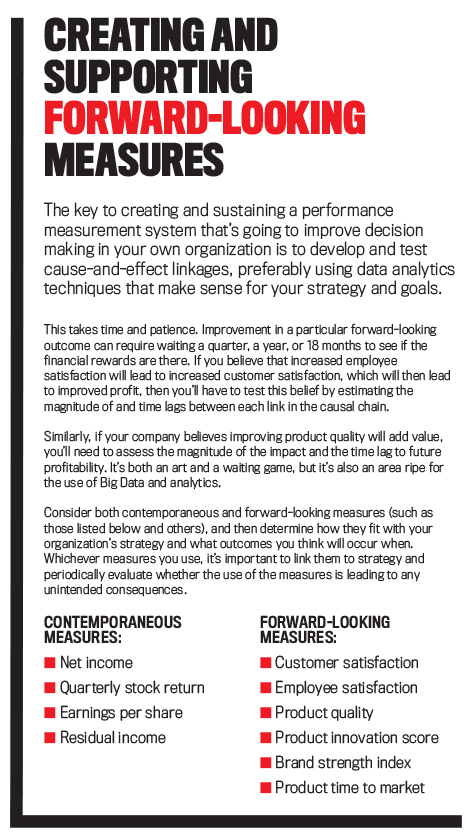

Choosing performance measures that capture progress toward strategic goals has long been an important topic for organizations. To provide a framework for that process, performance measures can be classified into two broad categories: contemporaneous measures and forward-looking measures. Contemporaneous performance measures, such as accounting profit, provide information about how employees’ resource- and effort-allocation choices affect the current performance of the organization but little to no information about how those choices will affect future performance. In contrast, forward-looking performance measures, such as quality, can be leading indicators of future performance.

Let’s take the example of a restaurant again and consider what these two types of measures tell us about its performance. Accounting profit captures how many customers were served and at what prices and costs. But it doesn’t capture how many of those customers will come back because they enjoyed high-quality food, great service, or both. In contrast, measures of food quality or service quality can shed light on this question. As mentioned before, if the quality of food or service is high on a given day, at least some customers may return to the restaurant another time, leading to more customers served in the long run, perhaps even at higher menu prices.

Now back to the challenges identified earlier: How can forward-looking measures be used to effectively help employees understand cause-and-effect linkages and motivate them to take actions accordingly? Let’s take a closer look.

THE EMPLOYEE FACTOR

How employees view their jobs can have a critical impact on the effectiveness of using forward-looking measures. Why? Because their perspective influences the way measures can be targeted: by emphasizing an understanding of cause-and-effect linkages or motivating action.

As with the types of performance measures, the way employees view their jobs can be classified into two broad categories depending on how long they intend to remain with the company: a short-horizon view and a long-horizon view. Their views may be influenced by their work environments, personal situations, or myriad other factors, but, regardless of the source of those views, organizations need to consider how these views impact employees’ choices in the workplace.

Let’s start with short-horizon employees. They could have their sights set on their next big job or on retirement, or they may work in an industry where turnover is high, such as retail or food service. These employees likely care most about making choices that increase organizational performance in the short term since they don’t plan to be around long enough to reap any benefits that may come with long-term gains. Take restaurant workers again. If they’re short-horizon employees, they may be all about speeding up food preparation and service to get more customers because this can increase their tips, and they have much less of a stake in whether customers will return for another meal.

So the challenge companies need to address with forward-looking measures is the action-focused one—motivating employees to do things that benefit the organization’s long-term performance.

Now consider long-horizon employees. These folks do care about long-term organizational performance since they can reap any future benefits that come with it. While restaurant employees with a long horizon certainly care about their tip income, they also want repeat customers because they’ll benefit from the restaurant’s long-term success, too.

THE LURE OF IMMEDIATE REWARDS

Nevertheless, a great deal of research shows that people frequently make choices that have immediate benefits even if doing so reduces the long-term benefits. This should come as no surprise—there’s plenty of evidence that shows people have a hard time choosing to exercise or save money today even though they know that they’ll benefit tomorrow. These choices are all the more difficult in an organizational setting, where short- and long-term cause-and-effect relationships can be anything but obvious. Without a crystal-clear understanding of how to allocate resources and effort today, employees will tend to overinvest in actions that increase current-period performance to the detriment of future performance.

So companies have a different challenge with long-horizon employees because these people are already motivated to take actions that will benefit the organization in the long term. Instead, the challenge companies need to address with forward-looking measures is the one focused on understanding. In other words, forward-looking measures need to be explained in a way that will help employees understand cause-and-effect linkages so they can take actions that benefit the firm’s long-term performance.

The problem is that it’s difficult, if not impossible, to know which employees view their jobs with a short time horizon and which ones take the long view. (An exception might be employees working in a fast-food franchise, the majority of whom are part-time.) Two research studies conducted by coauthors of this article—Anne Farrell of Miami University and Kathryn Kadous and Kristy Towry of Emory University—shed light on how organizations can use forward-looking measures without having this specific knowledge.

STUDY 1: THE COMPENSATION ANGLE

The first research study, published in 2008, examined the use of contemporaneous and forward-looking performance measures in the compensation plans of employees with short and long horizons.

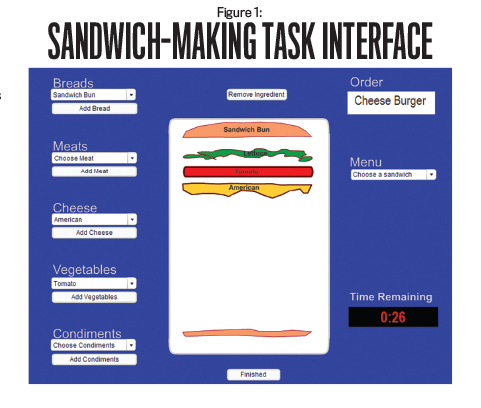

Using a game-like computer task, a group of 80 undergraduate business students each played the role of an employee who makes sandwiches to order at a virtual sandwich shop over 12 work periods. (Figure 1 shows the interface used in the task.) In each work period, the participants had to decide how to allocate their effort between producing high-quality sandwiches vs. producing a greater quantity of sandwiches of lower quality (subject to a quality threshold). At the end of each work period, participants received feedback summarizing sandwich production quantity and quality, sandwich shop revenue, and pay so they could refine their understanding of how best to allocate their effort. Sandwich quality is a leading indicator of future financial performance for the shop. Specifically, quality in one work period affects prices in the next period. The measure of quality is average errors per sandwich, so higher values (more errors per sandwich) indicate that participants focused less on production quality (and thus future performance) and more on production quantity (and thus current performance).

Participants’ pay was based on either 5% of the revenue from all sandwiches they made and sold or 5% of the revenue only from sandwiches that were prepared exactly as described on the menu. As such, the former group’s pay was tied to a contemporaneous performance measure (since total shop revenue for a period didn’t capture quality efforts), while the latter group’s pay was tied to a forward-looking measure (since shop revenue from only perfect sandwiches captures quality efforts). Essentially, this description of pay informed participants whether it was an important goal of the sandwich shop to produce quality sandwiches.

The students were also told that they either worked at a different sandwich shop every work period (a short horizon) or at the same sandwich shop across all work periods (a long horizon). Thus, the former group had no reason to be concerned about quality since their pay wouldn’t be impacted by the lead-lag relationship between quality and price, while the latter group did have reason to care about quality.

WHAT THE FIRST STUDY REVEALED

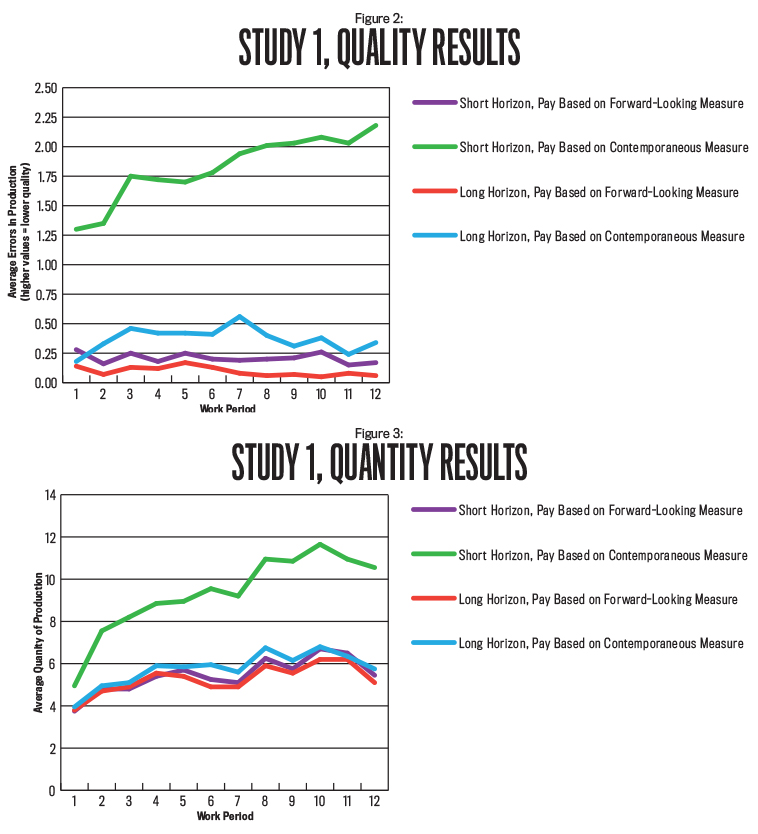

Participants with the short horizon allocated significantly more effort to quality (the optimal strategy for maximizing long-term performance) when their pay was based on the forward-looking performance measure rather than the contemporaneous measure (see the purple and green lines, respectively, of Figure 2; note that, hereafter, any differences reported are statistically significant). Notably, for those compensated with the contemporaneous measure, the focus on quality was far lower (Figure 2, green line), and the focus on producing as many sandwiches as possible (Figure 3, green line) was far higher—and thus far less optimal—than for any of the other three groups.

Bottom line: Tying compensation to forward-looking performance measures can be an effective way for companies to meet the challenge of motivating employees with short horizons to take actions that benefit long-term performance.

As expected, motivation wasn’t the challenge for participants with long horizons. Regardless of how they were paid, their focus on both quality and quantity (Figures 2 and 3, red and blue lines) was comparable to that of short-horizon participants paid based on the forward-looking performance measure (Figures 2 and 3, purple line). An interesting finding was that long-horizon participants’ focus on quality was significantly higher when pay was based on the forward-looking measure rather than the contemporaneous measure (Figure 2, red and blue lines, respectively). Analyses indicate that tying pay to the forward-looking measure helped participants more quickly identify the optimal strategy to complete the task. That is, for employees with long horizons, tying compensation to forward-looking measures isn’t necessary for motivational purposes, but it can be an effective way for organizations to meet the challenge of helping workers more quickly understand the best strategy for doing their task.

In short, results of this study indicate that tying compensation to forward-looking performance measures, rather than contemporaneous measures, can be an effective way for organizations to help all employees improve overall performance, regardless of horizon. It motivates short-horizon employees to take actions that maximize long-term performance, and it facilitates goal-consistent behavior for long-horizon employees.

WHAT’S THE CATCH?

If tying compensation to forward-looking performance measures is an effective way to help all employees, why doesn’t every organization do it? One possible answer is that it’s costly.

First, providing performance-based compensation (rather than a fixed wage) in and of itself is costly regardless of the performance measure used since employers must include a risk premium in employees’ compensation. For employees with short horizons, however, it’s possible that performance-based compensation may be the only viable option to motivate them into maximizing long-term performance since monetary incentives are clearly a powerful motivational tool.

Second, developing information about cause-and-effect linkages also is expensive. Certainly, top managers in organizations can use their experiences, beliefs, and intuitions to develop qualitative models of cause-and-effect linkages, communicate these to employees, and let them take it from there when it comes to deciding how to best allocate their resources and time on a day-to-day basis. While developing these qualitative models takes time, it’s less expensive than taking the next step to statistically validate these models and then provide and explain the quantitative details to employees to help them make better decisions.

The question, then, becomes whether qualitative or quantitative information reaps the most benefits in terms of better long-term organizational performance. That’s what the coauthors’ second research study, published in 2012, was designed to find out.

STUDY 2: CAUSE-AND-EFFECT LINKAGES

The second study also involved the sandwich shop scenario, with quality used as a leading indicator of future organizational performance. This study, however, didn’t focus on employees’ time horizons. While results of the first study shed light on how to motivate short-horizon employees, this study instead focused on how to best help long-horizon employees understand cause-and-effect linkages. Specifically, it examined the nature of the information the company gave employees about cause-and-effect linkages—in particular, the link between quality today and price tomorrow.

The participants were 77 undergraduate business students who were randomly divided into three groups. One group received no information about cause-and-effect linkages. They were told only that sandwich prices “may rise or fall in subsequent periods.” This is analogous to companies that provide employees with performance measures for decision making but not information about relationships between those measures.

The second group received qualitative information about cause-and-effect linkages. They were told “the price may rise or fall in subsequent periods depending on the quality of sandwiches produced in prior periods.” This can be compared to organizations in which top managers develop models of cause-and-effect linkages between performance measures based on their experiences, beliefs, and intuitions but don’t statistically validate those models.

Finally, the third group of participants received quantitative information: “If in a given work period there’s an average of one or fewer mistakes per sandwich, the sandwich price in the next period will be 10% higher; more than one but less than two mistakes per sandwich, the sandwich price in the next period will remain the same; or two or more mistakes per sandwich, the sandwich price in the next period will be 10% lower.” This is analogous to organizations that have developed and statistically validated models of cause-and-effect linkages.

In all scenarios, participants’ pay was based on 5% of the revenue from all sandwiches they made and sold; in other words, it reflected a contemporaneous performance measure that provided information about how their choices affected current but not future sandwich shop performance. Holding constant the way participants were paid across all three scenarios allowed the researchers to isolate the effect of communications about cause-and-effect linkages.

INFORMATION IS KEY

Compared to providing no information about cause-and-effect linkages (Figure 4, blue line), communicating either qualitative or quantitative information (Figure 4, red and green lines, respectively) significantly improved the extent to which participants focused on quality. There was no significant difference in the quality focus when either qualitative or quantitative information about cause-and-effect linkages was provided. As such, either kind of information can benefit employees, so the choice of which to give them can be based on the costs to develop and distribute the information.

It’s a challenge to motivate all employees to maximize the organization’s long-term performance as well as help them understand the cause-and-effect linkages between their actions today and the organization’s performance tomorrow so that they can meet that goal. Forward-looking performance measures are a tool to use in both views, regardless of whether or not employees are planning to be with the organization for the long term. By tying compensation to these measures or providing details about the linkages for decision-making purposes, organizations can meet this challenge. That makes for happy, empowered, motivated employees as well—a win-win for both sides!

July 2017