IS INFORMATION ECONOMICS ENOUGH?

Many experts suggest that assuring 100% privacy is akin to achieving 100% quality: zero defects. Indeed, an organization’s strategy to assure the privacy of data is a function of the goals set forth by management and management accountants. If there are no goals and objectives regarding privacy, then assuring and achieving it is very unlikely.

A common strategy in organizations today is to use an “information economics” approach to managing privacy, which is basically a cost-benefit approach. Unfortunately, because this is essentially a “by default” strategy, it’s a reactionary approach. Goals, objectives, and control plans regarding privacy aren’t implemented, designed, or even discussed until something goes wrong and lack-of-privacy costs have been incurred. In other words, management and management accountants don’t do anything about privacy until data escapes—at which time the breach might seriously damage the organization.

Before anyone accuses us of finger-pointing, we aren’t saying that management accountants don’t secure information. Both IMA (Institute of Management Accountants) and the AICPA (American Institute of Certified Public Accountants) have emphasized the importance of information security for many years. Now the emphasis is on privacy, which isn’t the same thing as information security. Some of the controls for security may also ensure privacy, but not entirely. Security refers to the safeguarding of information so that it isn’t damaged or stolen. Privacy refers to data that can’t be observed by others. Privacy goes beyond security; the privacy of data that is secure can easily be violated.

With this in mind, management accountants must take a forward-thinking approach and weigh the costs of keeping data against the benefits. But this is possible only when management accountants realize that all data must have expiration dates. With today’s data applications, accountants can do more than just label data with an expiration date; they can make data disappear at the expiration date. Several existing smartphone apps, such as Snapchat and Confide, already provide users with the capability to make text, data, and even photos disappear after a date that they choose. Of course, management accountants must consider the legal requirements for keeping data for certain lengths of time (see “How Long Must You Keep Your Data?” below), but all data should now be accompanied by a “delete” function that’s triggered automatically by an expiration date.

WHEN HAS DATA GONE BAD?

The benefits of keeping data won’t come as much of a surprise to most management accountants since they include such advantages as facilitating the creation of information using data analytics, generating financial statements and other reports, and complying with legal requirements.

But there’s risk in keeping data. Some of this risk can be explained by mistakes and errors, but in modern enterprises the risk is almost entirely a function of loss of privacy. Data storage inherently contains this risk: Some data is more sensitive to loss of privacy and thus is riskier than other data. It’s constant and doesn’t go away. At some point, however, the risk of keeping data is greater than the benefit. The data has essentially expired at this point and should be deleted.

The creation of an “active” expiration date—one at which data will actually be deleted—is essential to ensuring privacy in modern organizations. This type of control plan must be tested carefully before implementation, and conditions must be monitored closely to determine whether expiration dates should change. If management accountants can implement an active expiration date but can’t change and monitor it effectively as conditions warrant, then the plan should be scrapped.

Additionally, organizations should plan to place expiration dates on all data because even seemingly unimportant data can pose privacy risks. For example, an information system might include a photo of accountants and customers working together at an upstream supply-chain partner. Harmless enough, right? Modern cameras are usually GPS-enabled, which means they include latitude and longitude measures that are imbedded in the metadata that accompany photos. If this photo escapes the system, the exact geographical location where the photo was taken will be public knowledge. This may violate the customer’s expectations for privacy. Likewise, even simple vacation photos can pose privacy risks.

A QUALITY-BASED STRATEGY FOR MANAGING PRIVACY

Given that privacy is now a quality issue, and failures in terms of privacy can damage a company’s income and reputation, it’s essential that management accountants manage privacy as a matter of quality. With the most recently reported cost of a data breach in a U.S. company now averaging more than $200 per record lost, it’s essential that organizations put in place plans to report, manage, and control these costs.

After management sets its goals for achieving quality, privacy costs occur in two categories: (1) costs that arise because privacy breaches may occur—i.e., costs of complying with management’s privacy goals, and (2) costs that arise because privacy breaches have occurred—i.e., the costs of noncompliance with those privacy goals. Each of these two cost categories—costs of compliance and costs of noncompliance—has two subcategories. The costs of compliance include both prevention costs and appraisal costs. The costs of noncompliance include both internal and external failure costs. As is the case with environmental-quality costs, external failure costs can be further subdivided into two categories: costs borne directly by the organization and those borne by third parties in the company’s external value chain. (Table 1 lists typical cost-creating activities in each category.)

Management accountants measure the costs associated with the activities mentioned in Table 1 and use them to manage privacy. At a minimum, these activities include creating and staffing an information security department—headed by a chief information security officer (CISO)—that’s supported by data privacy teams deployed throughout all functional areas of the organization; development, maintenance, and review of a comprehensive policy and procedures manual for control of sensitive information; data assessment for purposes of creating and maintaining an active inventory of all potentially sensitive data housed anywhere within the organization, including a complete inventory of all access points to that data; data warehousing and storage; and training all employees to respect privacy and recognize threats to privacy while also constantly making them aware of the importance of confidentiality.

Prevention also involves control plans, such as active expiration dates and other modes of data disposal. Costs include those associated with implementing and monitoring the plans over time. Indeed, the time frame for a privacy-cost model is greater than one year, and some management accountants include discounting cash flows (net present values) as part of their analyses. Additional control plans, such as locks, passwords, encryption, and other controlled-access methods, add costs as well.

Appraisal costs, on the other hand, result from activities designed to identify whether the privacy controls are working as intended to prevent the loss of sensitive information. They include routine penetration testing; validation of hardware security modules; validation of automated compliance software and other intrusion-detection systems, including data loss prevention tools; monitoring network activity logs; and testing the effectiveness of the various access and active expiration-date controls.

Further, the effectiveness of all perimeter controls (e.g., firewalls) must be tested regularly. Locks and other physical deterrents, such as traditional third-party-monitored security alarm systems, should also be validated regularly as part of the appraisal process. Routine policy compliance audits (to ascertain whether employees are following company policy regarding the protection of sensitive information) are another important aspect of the appraisal process, as many vulnerabilities to data loss arise because of careless employee behaviors like leaving sensitive documents on the desk of an unlocked office or leaving computers unattended for even very brief periods.

MORE FAILURES = MORE COSTS

When prevention and appraisal activities aren’t effective, failure costs can pile up. Internal failure costs—the costs of actual and potential breaches that are detected internally by the organization as a result of the appraisal process—are far less costly to the organization than external failures in which individuals become victims of a privacy breach. (Some management accountants view internal failure costs as a good thing because the company was successful in detecting the lapses.) Activities associated with internal failure costs include disciplinary measures and remedial employee training when policy violations are identified; reengineering of compromised systems, including rewriting code and various at-risk web applications; investigations of unusual network traffic; and lost revenue and/or productivity due to system downtime during the remediation process. In regard to active expiration-date controls, an internal failure might arise when needed data isn’t available because the expiration dates were too static and couldn’t be changed when conditions warranted.

External failure costs—the costs associated with an actual loss of sensitive information to someone outside the organization—are far more troublesome than internal failure costs because they can be exponential in nature and can have long-lasting, negative consequences. Some external failure costs are borne by the organization, while others are ultimately borne by the third-party victims of the organization’s failure. These indirect external failure costs, which border on being unmeasurable, are called external value chain costs.

External failures might result from undetected security threats, failure to follow data security and destruction policies, setting data expiration dates too late, failure to update security software, failure to engage security devices, and so on. As a result, the business may be on the hook for costs for everything from investigating the breach to fines and penalties to hiring public relations experts to mitigate the negative impact of the failure. These costs escalate quickly. Further, because they’re often difficult to quantify, they’re vulnerable to significant underestimation. For example, how do you quantify the cost that a privacy breach wreaks upon your company’s reputation? How do you estimate the impact of lost customers on its short- and long-term revenue streams?

As we alluded to earlier, the offending organization isn’t the only party that suffers financially from external failures. The various affected parties in the organization’s external value chain incur costs for which they’re rarely fully compensated. For example, individual employees or customers may be unable to obtain a loan while they are still in the process of restoring their stolen identities.

Suppliers or commercial customers who might have had data compromised also find themselves incurring the same types of external failure costs borne by the company. Beyond the tangible direct costs of remediating the impacts of the failure on their own systems, they, too, must struggle to minimize the impact of the victimization on their own brand images and reputations.

MANAGING PRIVACY COSTS TAKES SKILL

After identifying and assigning costs to the activities related to data privacy, there are two approaches to managing these costs. Both are straightforward, though one is intuitively less attractive than the other. The first approach focuses on achieving an “optimal” balance between the costs of compliance (prevention and appraisal) and noncompliance (internal failure, external failure, and external value chain costs).

Research using quality-cost models over the past 30 years suggests that, mathematically, the total cost of privacy is minimized at the point where the compliance costs equal the noncompliance costs (see Figure 1). In this approach, management spends enough money on prevention and appraisal to equal the total costs of noncompliance, thereby minimizing total privacy costs. This approach would work well if all the costs of both compliance and noncompliance have been identified and accurately quantified and if the underlying model is, in fact, a static one. Unfortunately, neither of these conditions is likely to hold true.

As for the first assumption, it’s highly unlikely that all costs of privacy can be identified and quantified accurately. For instance, it’s particularly difficult to measure external failure costs, both to the firm and to affected third parties. How can a management accountant possibly be expected to quantify every aspect of external failure costs—all of the lost sales, the damage to the company’s and third-parties’ reputations, the suppliers’ lack of faith in the company, and the sheer embarrassment incurred when dealing with the media? Because external failure and external value chain costs are likely to be much higher than a company will calculate, the act of setting total compliance spending at an amount equal to the total identified noncompliance costs won’t minimize total privacy costs.

The second assumption, that the model is a static one, ignores reality. The environment in which data privacy issues arise is dynamic. New technologies and knowledge capabilities make compliance less costly on the one hand, while the increasingly shorter life cycles of system controls lead to new vulnerabilities and greater threats of breaches. Instead of a static model, the more realistic dynamic model is one in which the compliance curve (shown in Figure 1) is continually shifting downward while the noncompliance curve is continually shifting upward.

In light of these continually shifting cost curves, a second, more strategic approach to managing data privacy costs is to focus as much attention as possible on prevention activities. In today’s business environment, the best way to manage privacy is to maximize the investment in prevention. In short, management accountants must plan for “zero privacy defects” in order to protect both the image and the income of the enterprise, as well as those of the other participants in its value chain. In support of this effort, data-privacy cost goals should be included as an integral feature of a company’s balanced scorecard and should be monitored regularly. Formal data privacy cost reporting, review, and analysis should become an integral part of the firm’s cost-management activities.

WHAT IT ALL MEANS FOR YOU AND YOUR COMPANY

In the age of Big Data, management accountants must continue to be the data caretakers they’ve always been. This means they must learn to treat privacy as a matter of quality. The first step is to develop new control plans that include active expiration dates. Much as expiration dates on perishables serve as indicators to pull the items from the shelves, an organization’s active expiration dates must actually trigger deletion of the data once the risk of keeping it outweighs the benefits.

Of course, these new control plans are simply the first steps in creating strategic plans with goals and objectives for safeguarding privacy. Management accountants can calculate the costs of achieving high-quality privacy by comparing the costs of trying to achieve privacy goals (compliance) to the costs of not achieving them (noncompliance). After calculating these costs and realizing that the costs of external failure—especially external value chain costs—are phenomenally high, it will be clear to everyone that the only solution is to focus on prevention.

While it’s difficult to accomplish given the constant changes in technology, laws, and regulations, the complete elimination of privacy failures should be an important goal of any high-quality 21st Century organization.

HOW LONG MUST YOU KEEP YOUR DATA?

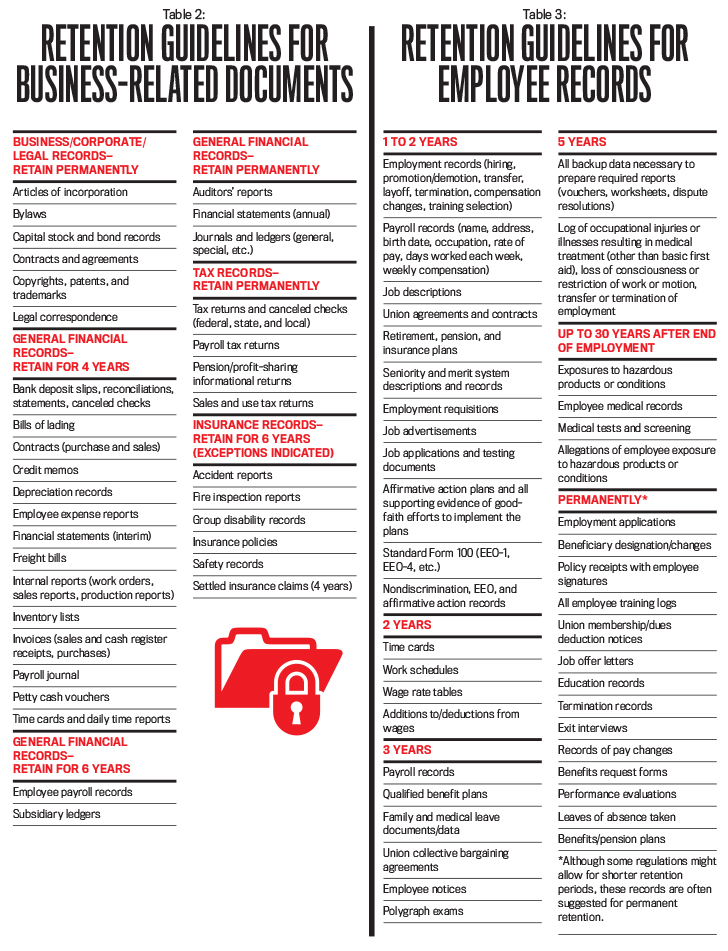

No strategic plan for privacy is complete without a data retention plan. Your organization’s plan—based on numerous laws, regulations, and guidelines—delineates the minimum amount of time data must be kept before it can be deleted using active expiration dates. The retention periods in Tables 2 and 3 are based on U.S. federal regulations, where applicable, and the more conservative recommendations made by various lawyers, Certified Management Accountants, and Certified Public Accountants.

Note that these tables apply to U.S.-based organizations; multinational organizations will face international retention requirements as well. As shown in them, record retention requirements can be classified into three types: (1) general business and legal records; (2) accounting, financial, and tax records; and (3) regulations-based records.

While Tables 2 and 3 are based on common business practices and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requirements, there are numerous other organizations that have the power to proclaim or extend the required data retention periods. Review these requirements carefully when designing any plans for information privacy. For example, the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), in conjunction with the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), requires that electronic business records be retained three to six years. Further, says SEC Rule 17a-4, messages must be stored in their original form on tamperproof, nonrewriteable, and nonerasable media in duplicate and in separate locations. The SEC also requires archived messages to be time/date stamped and serialized, indexed, and searchable.

Companies must have an auditing system in place and store audit records, and they must appoint an independent third-party downloader to access the organization’s electronic records.Other organizations/acts that can affect data retention policies include the Vietnam Era Veterans Readjustment Assistance Act, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Fair Labor Standards Act, the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), the Civil Rights Act, the Family and Medical Leave Act, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), IRS/Treasury regulations, the Davis-Bacon Act, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Walsh-Healey Public Contracts Act, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), and numerous state and local laws. Table 3 is based on the requirements of some of these (and other) organizations/acts.

January 2017