In situations where a company is unsure if the tax treatment of a transaction is in total compliance with the tax code, it can still record the transaction and claim the tax benefit as long as it also classifies the transaction as an uncertain tax position (UTP). Doing that requires following the guidelines set forth in Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Interpretation No. 48 (FIN 48), “Accounting for Uncertainty in Income Taxes.”

FIN 48 requires a two-step procedure when recording a UTP: recognition and measurement. The recognition step is based on a “more likely than not” threshold. The company determines if the probability is 50% or greater that the evidence will support the tax position and withstand scrutiny (assuming the IRS has full knowledge of all the relevant information regarding the tax transaction).

If the organization decides that the tax position meets the threshold, then the measurement step is performed to determine the tax reserve to be claimed for the transaction. Also known as tax cushions, tax reserves are a contingent liability the company must record within its financial statement in case the tax benefit is challenged and reversed by the IRS. The contingent liability basically equals the company’s estimation of additional tax expenses that could be incurred after a potential IRS audit. The tax contingent liability is many times referred to as the “unrecognized tax benefit.”

The amount of the tax reserve is determined by using the largest amount of benefit that is greater than 50% likely to be realized upon settlement. Common examples of UTPs include characterizing gains or losses as capital gains or losses, claiming a tax credit, and taking a tax deduction in the current tax year.

DETECTING ISSUES OF CONCERN

When FIN 48 was initially announced in 2006, the IRS stated that it would use the FIN 48 disclosure as a roadmap to detect audit issues. But apparently FIN 48 wasn’t providing enough or adequate information, so the IRS introduced Schedule UTP in 2010 to get more, better detailed information about a company’s UTPs. Specifically, Schedule UTP requires the reporting company to list all UTPs individually (rather than in an aggregate disclosure, as previously done). UTPs are defined by FIN 48’s guidelines, but they also include tax positions that don’t have a tax reserve because the company expects to litigate the position.

At the time Schedule UTP was introduced, then-IRS Commissioner Douglas Shulman stated that two of the goals for Schedule UTP are to “cut down the time it takes to find issues and complete an audit” and to “help us prioritize taxpayers for examination.” It’s clear that the purpose of Schedule UTP is to be an additional audit tool for the IRS.

Within Schedule UTP, an organization must rank all UTPs based on the U.S. federal income tax reserve and provide a concise description of each one. In addition, it must disclose UTPs whose reserves each comprise 10% or more of the aggregate reserve. It also must disclose whether the tax position will create a permanent or temporary tax difference.

Schedule UTP was gradually introduced to corporate tax filers. For 2010 and 2011, companies with total assets of $100 million or more had to submit the schedule. For 2012 and 2013, it was required for companies with total assets of $50 million or more. Starting in 2014, all companies with total assets of $10 million or more had to submit the schedule.

THE REACTION

Before Schedule UTP was required to be filed, there was a lot of speculation about how companies would respond. Would they change their tax reporting behavior to minimize the risk of a UTP being reversed? Would they reclassify a UTP as a certain tax position to avoid disclosing it? Would Schedule UTP have more of a smoke-and-mirrors effect and not be as effective as advertised?

How companies reacted to Schedule UTP was important because it influenced the strategic interactions between the IRS and companies. The IRS not only had information from a reporting company’s risk strategy, but the Service also had information from the reporting of other companies in similar industries, giving it more leverage in monitoring companies’ activities. And when it releases data on this reporting, companies themselves could also observe how and to what degree others are reporting UTPs.

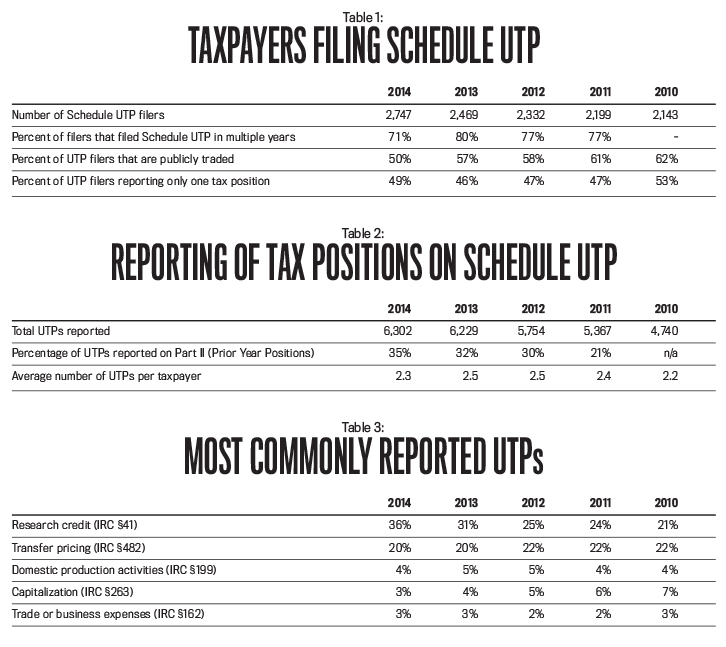

The IRS now has six years of data collected from large corporations and four years of reporting from midsize corporations. The number of firms filing a Schedule UTP increased for the first five years (see Table 1), which isn’t a surprise considering that Schedule UTP was phased in over time.

Interestingly, about half of the companies that filed Schedule UTP reported only one UTP. The other 50% of filers report an average of two UTPs per filing (see Table 2). This is surprising because research has found that companies report tax reserves ranging from 1%-2% of their total assets in the tabular reconciliation within their financial statements, per FIN 48’s guidelines. That’s a large reserve given that companies report on average one to two UTPs on Schedule UTP. For that amount, you’d expect multiple UTPs that might need to be covered.

The total number of UTPs reported increased over the years, which again seems logical given the way the schedule was phased in by beginning with companies with total assets of $100 million or more and gradually adding companies until even those with $10 million or more in total assets were required to file it. You would expect the number of companies reporting such tax positions to significantly increase in both 2012 and 2014 as more companies were required to file in those years. Yet Table 2 shows there weren’t any significant jumps. Rather, the number of UTPs steadily increased year over year. It’s difficult to determine or explain why there wasn’t a significant increase in years 2012 and 2014. Perhaps companies became more comfortable with the filing requirements and how or whether to classify UTPs. Another possibility is that companies new to filing the schedule were better prepared to file their schedule.

Table 3 shows the most commonly reported UTPs by year. The research credit (IRC §41) is the most common, followed by transfer pricing (IRC §482), domestic production activities (IRC §199), capitalization (IRC §263), and trade or business expenses (IRC §162).

A common question that arises from the tax community is “Why don’t taxpayers reclassify a UTP as a certain tax position so they don’t have to disclose it?” The IRS is aware of this scenario. Lisa Rupert, an IRS compliance management team member in the Large Business and International division, said “Those taxpayers that did not file a Schedule UTP are saying, ‘Hey, we’re good to go, we don’t have anything uncertain in our return, we’re good to go, don’t worry about us.’” They reduced their pretax book income by “more than twice as much. And those are the ones saying, ‘nothing uncertain here. No need to look at us.’” Aware of this possibility, the IRS uses analytical models to flag specific taxpaying organizations that fall into this category. Rupert further states that “[The IRS] could potentially build models to identify the same uncertainty in those that don’t file” the schedule.

In addition, the IRS has various audit tools to conduct analytical analysis that it can use in conjunction with Schedule UTP, such as the FIN 48 disclosure. IRS Chief Counsel Donald Korb stated that the IRS is “not going to turn a blind eye” to FIN 48, but use it with Schedule UTP to effectively identify tax positions and companies that aren’t in full compliance with the tax code. The IRS can use the tax reserves reported under FIN 48 and make inferences about why an organization didn’t report certain UTPs that others are reporting. The IRS already has a list of common UTPs historically disclosed and is utilizing this information as a benchmark for its assessments.

Most organizations properly disclosed their UTPs. About 3% of those reporting failed to satisfy the detail description requirement of the UTP in the first year. The IRS wants a full description rather than one sentence stating the nature of the position. For example, some companies were simply stating that the UTP was related to an R&D credit rather than stating the specific issue that made the R&D credit uncertain.

THE IMPACT

Companies generally see Schedule UTP as a disadvantage during the audit process because it requires them to disclose their weak and uncertain tax positions. In 2012, however, IRS Deputy Commissioner Steven Miller noted that, while Schedule UTP is used to detect audit issues, it’s also used to identify returns that don’t need further attention. This is in line with other studies, such as a 2010 report by Lillian F. Mills, Leslie A. Robinson, and Richard C. Sansing (“FIN 48 and Tax Compliance,” The Accounting Review, vol. 85, no. 5) and one that we wrote in 2015 (Robert Lee and Anthony Curatola, “The Effect of Detection Risk on Uncertain Tax Position Reporting: Experimental Evidence,” Advances in Taxation, vol. 22), which argue that Schedule UTP can help deter the IRS from auditing organizations that have strong and clean tax reporting behavior.

What remains unclear is whether businesses will collectively or individually change their reporting of UTPs under Schedule UTP. The data is still relatively new, and the IRS is still learning how to fully integrate Schedule UTP into its audit process. Moreover, companies with revenues between $10 million and $50 million only began reporting this information in 2014.

But changes in how organizations report UTPs may make for some entertaining review. For example, if they collectively begin to treat risky UTPs as certain tax transactions instead, then the IRS can lose its advantage in detecting these specific issues. This, in turn, could lead to more intense audits where the IRS looks for the omitted reporting. Conversely, if only a few industries change their reporting behavior, the IRS may be able to use that data to establish benchmarks for particular industries and thus concentrate its audits on those not reporting UTPs. A key component within this strategic interaction is how each company within an industry is going to respond to Schedule UTP.

DEFENDING UTP DECISIONS

Schedule UTP impacts management accountants regardless of whether they are directly or indirectly involved with their company’s tax reporting. Three common UTPs—research credits, transfer pricing, and capitalization—are areas that management accountants oversee. Management accountants participate in the discussions concerning the amount of funds allocated toward their company’s research and development budget, which impact whether the research expenditures qualify for the research credit. Likewise, they oversee transfer pricing within their companies as well as capital investments, which is influenced by capitalization.

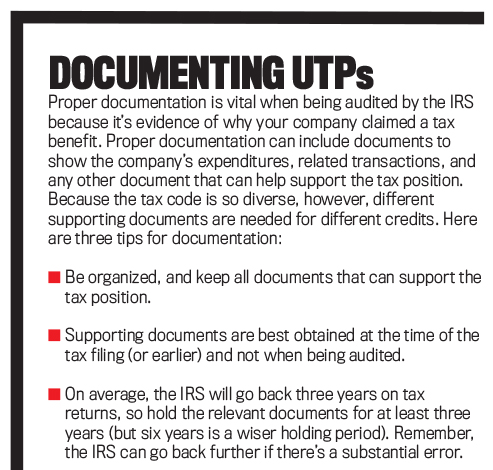

Going forward, it’s important to maintain proper documentation and evidence to support an organization’s decisions, specifically when the decisions are tied to tax implications that likely won’t come under IRS scrutiny until a few years after the Schedule UTP is filed (see “Documenting UTPs” above). In this regard, time is on the side of the IRS, which can sit back and collect data for different companies over time and then determine whether corporations are taking less risky positions or reassessing various transactions.

January 2017