If you’ve ever thought about a career in academia, now’s a great time to get serious about making a switch because there continues to be a shortage of qualified accounting faculty at the doctorate level in the United States. While the number of students enrolled in accounting Ph.D. programs has increased over the last decade, there still aren’t enough qualified accounting faculty to meet the demand. And that means students suffer the most in the long run. A study published in the June 2014 issue of Accounting Horizons, “Lessons Not Learned: Why is There Still a Crisis-Level Shortage of Accounting Ph.D.s?” noted that approximately 70% of accounting program administrators reported their programs had been harmed by the shortage of qualified faculty with advanced degrees. Many programs were forced to increase class sizes or trim the number of elective courses they offer in both undergraduate and graduate programs. In addition, the study found that fewer than half (46%) of doctoral accounting program coordinators reported a majority of their students had two or more years of professional work experience.

ADDRESSING THE SHORTAGE

The accounting profession has undertaken a number of strategies in recent years to recruit more accounting faculty, and we’ll discuss a few here. The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) International created the AACSB Bridge Program as a means of enabling business leaders to move from industry to academia. This intensive, five-day program is open to senior-level business professionals from all industries and disciplines, but applicants must meet the requirements for instructional practitioner status at AACSB-accredited schools. More information is available on the AACSB’s website (www.aacsb.edu).

The Accounting Doctoral Scholars (ADS) Program represents the largest investment ever made by the accounting profession to address the shortage of accounting faculty members—especially in the areas of audit and taxation. The program, which began in 2008, has been funded to the tune of more than $17 million by accounting firms, state CPA societies, the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA) Foundation, and others. Since its inception, the program has helped more than 100 accounting professionals transition into academic careers. Although the program was modified in 2016, it still provides up to $40,000 of funding for CPAs who have at least three years of professional work experience. This funding is in addition to any financial support provided by the student’s university.

In addition, IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) provides two scholarship programs and one grant program for doctoral students. The IMA Research Foundation Doctoral Summer Research Scholarship Program provides financial support for Ph.D. candidates in accounting from accredited programs so they can work on their summer research paper instead of teaching or doing other research. The Doctoral Student Grant Program provides funding for research conducted in connection with a dissertation or other project. (See www.imanet.org/educators/research-foundation.) And the CMA Doctoral Scholarship Program helps recipients financially so they can study for and take the CMA® (Certified Management Accountant) exam at no cost. (See http://bit.ly/2nXwwDp.)

Another major development designed to address the shortage of qualified accounting faculty is the creation of nontraditional doctoral programs. While a traditional program consists of students returning to school full-time for three to five years, nontraditional programs allow professionals to continue to work while earning their doctoral degree (for more, see “Roadblocks on the Path to Academia”). Students attending nontraditional doctoral programs typically attend classes once a month, thereby helping to lessen the opportunity cost (lost income, essentially) of pursuing this education.

BEFORE YOU TAKE THE LEAP

If the thought of pursuing an advanced degree interests you, first ask yourself: Do I really want to teach? While some universities are more research intensive than others, faculty members at every university teach. To determine whether you enjoy teaching, apply for a position as a part-time adjunct professor at a local college or university. If your work travel schedule prevents you from teaching a traditional course, consider teaching an online course. While you won’t get any face-to-face interaction with students, you’ll become familiar with developing lesson plans, grading homework, preparing examinations, and using digital learning platforms. If you want to teach as an adjunct professor, most colleges and universities require a graduate degree and at least 18 semester hours of graduate credit in the field in which you’re teaching. Many colleges also require professional certification, such as the CMA or CPA (Certified Public Accountant) credential, to teach accounting courses.

The second consideration before entering a doctoral program is: What type of research do you want to conduct? If your goal is to conduct high-level academic research and focus more on research than teaching, look for a program that will be able to assist you in landing a job at another doctoral-granting institution when you graduate. But if you’d rather focus more on teaching and less on research, institutions that focus on preparing students for corporate life and have a balanced track of teaching and research will be a better fit. It’s also smart to read journals published by IMA, such as Strategic Finance, Management Accounting Quarterly, and the IMA Educational Case Journal, and the American Accounting Association (AAA), such as The Accounting Review, Accounting Horizons, and Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory. These journals will help you grasp the differences between practitioner-oriented research and academic research. While each type of research is valued at different universities, some schools place a much higher emphasis on academic research when granting tenure.

Another consideration is the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT). Most traditional institutions with Ph.D. programs in accounting will require applicants to achieve a high score on the GMAT before being admitted. A study published in the November 2012 edition of Issues in Accounting Education, “The Current State of Accounting Ph.D. Programs in the United States,” found that the average GMAT score for Ph.D. students nationwide was 692. Since most of the nontraditional programs admit only experienced professionals (some require at least 10 years of relatively high-level experience for admission), the GMAT requirement is often waived. Yet both types of programs usually will require a thorough interview and application process designed to ensure that incoming doctoral students are fully aware of the rigorous nature of academic training. So if you’re serious about going down this road, it’s a good idea to meet with both professors and current students in the program you’re interested in. You’d be wise to contact recent graduates, too, to learn their thoughts about the program, as well as to assess how difficult it was for them to find employment at the college or university of their choice when they graduated.

You also should consider costs. Most traditional accounting Ph.D. programs waive tuition (typically, both in-state and out-of-state tuitions are waived) and give salary stipends (usually $15,000 to $30,000 per year) for teaching introductory courses or serving as a research assistant. Therefore, if you’re an experienced professional, expect to suffer declines in income and opportunity costs in the form of lost promotions and bonuses.

And nontraditional doctoral programs aren’t inexpensive—some cost up to $100,000 for tuition, plus travel and hotel costs for out-of-towners—but classes meet primarily on weekends, which enables students to juggle both school and work commitments. An October 2013 article in Strategic Finance, “Blazing a Different Path—A Career in Academia,” compares the program lengths and tuition fees of six universities that offer nontraditional doctoral programs.

YOU’D BETTER LIKE RESEARCH

One thing worth noting: Whether you’re studying in a traditional or nontraditional doctoral program, it’s imperative to understand that these programs are not similar to Master of Business Administration or Master of Accountancy programs. The focus of accounting doctoral programs is to teach candidates to conduct accounting research. Toward that end, students will take courses in statistics and research methods to prepare them to conduct the sort of original research that will be required of them in their academic careers. The doctoral seminar courses concentrate on empirical studies in accounting research by topic—such as financial or managerial accounting, auditing, and taxation—and will require extensive reading and writing of research papers.

A common criticism of academic research is that it’s of little use to working professionals. A July 2012 report sponsored by the AAA and AICPA stated that accounting research, unlike research in law and medicine, often isn’t germane to accounting practitioners or corporate accountants. (The full report, which is available online, is titled The Pathways Commission: Charting a National Strategy for the Next Generation of Accountants.) Nevertheless, the authors of this report believe this criticism presents a perfect opportunity for accounting professionals to use their practical work experience to inform their research questions, both during their doctoral programs and during their academic careers, thereby helping bridge the gap between accounting practice and accounting research.

Another positive attribute of experienced accounting professionals is that they’re often perceived as being better teachers than professors without significant work experience. A study published in the November 2004 edition of Issues in Accounting Education, “The Importance of Relevant Practical Experience among Accounting Faculty: An Empirical Analysis of Students’ Perceptions,” reported that students perceived professors possessing relevant work experience to be of higher quality than professors lacking practical experience.

PROFILES IN ACCOUNTING ACADEMIA

To give you more of a “real world” perspective, the remainder of this article highlights the experiences of five accounting faculty members with significant public accounting and/or industry experience who have successfully transitioned into second careers in academia. Three of these professors earned their doctorates through traditional programs, while two completed a nontraditional program.

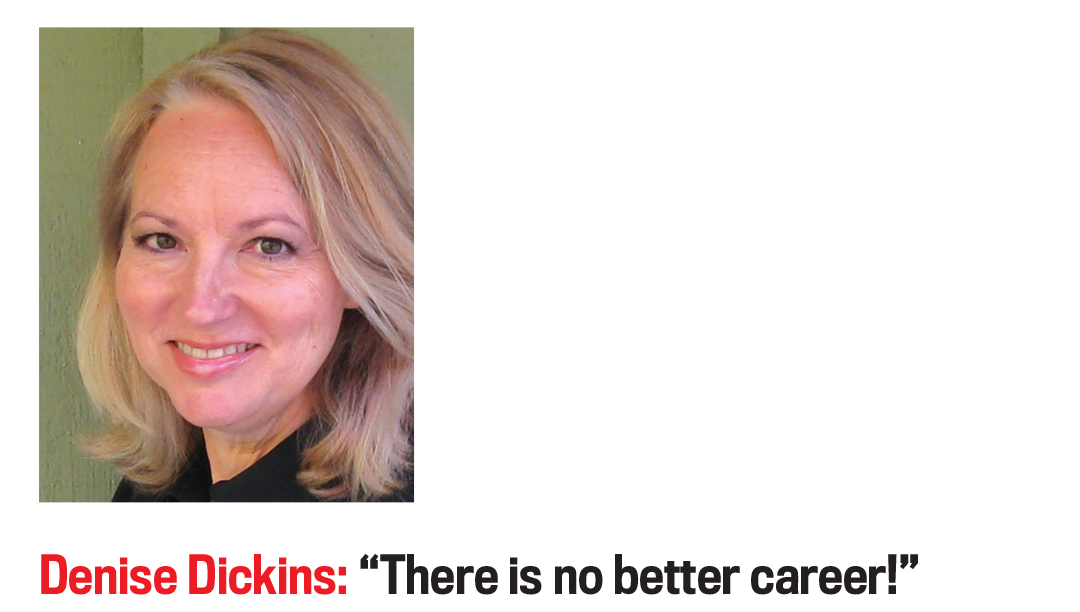

Denise Dickins worked for Arthur Andersen for 19 years, the last nine as the head of the South Florida audit division. The demise of Andersen prompted her to make a career change and enroll in the traditional doctoral program at Florida Atlantic University. Dickins says that her professional work experience definitely influenced her research projects, both during and after completion of the doctoral program.

“I questioned the results of some prior research, as they didn’t reflect my experience in practice,” she explains. “Most of my research starts with the goal of being informative to practice: ergo, most is practice-focused.” Dickins is currently an associate professor at East Carolina University, teaching courses in Auditing and Corporate Governance & Accounting Ethics—courses in which her public accounting experience proves invaluable. She’s also a member of the board of directors and cochair of the audit committee of Watsco, a publicly traded company that distributes heating, air conditioning, and refrigeration equipment, parts, and supplies.

Dickins accepted her first academic position nearly 10 years ago and is pleased with her decision to transition into academia: “There is no better career!” she enthuses. Moreover, she has been surprised by how much she has enjoyed the research aspects of her career. Her advice to those who are considering a similar career change: “Be prepared to work hard and grow a tough skin. The work is very demanding but also highly rewarding.”

Kim Honaker was a tax professional with 22 years of experience in both public accounting and industry, culminating with the position of director of Tax Operations with a publicly traded global technology company. While considering a career shift from industry to academia, Honaker learned of a relatively new and innovative nontraditional doctoral program at Kennesaw State University in Georgia. “I chose a nontraditional DBA (Doctor of Business Administration) program, primarily for two reasons: One, I valued the flexibility I would have in continuing to be able to work in the accounting/tax profession while pursuing my degree, and, two, as a professional with more than two decades of experience, I was interested in engaging with other experienced professionals—including those with experience outside of accounting.”

Honaker believes that her professional experience has served as the motivation for the bulk of her research. “Much of my research focuses on specific challenges to the profession that arise as a result of regulation, such as SOX, FIN 48, and IRS requirements for Schedule UTP reporting. In addition, my dissertation research was influenced by my exposure to different decision makers within different companies and my desire to better understand why different individuals reach such distinct judgments on similar issues.”

After completing her doctoral program in slightly more than three years, Honaker is currently an assistant professor at Middle Tennessee State University, where she teaches courses in Federal Income Taxation and Income Tax Research and Planning. Her advice to prospective doctoral students: “Know that, as with any new position, it takes some time to get comfortable with a new environment and new responsibilities. Second, when frustrations set in, remember that there’s something extremely encouraging about the fact that each semester is a chance to start over, to make new connections, and to perform just a little better than you did the last time. Not many jobs come with that sort of opportunity.”

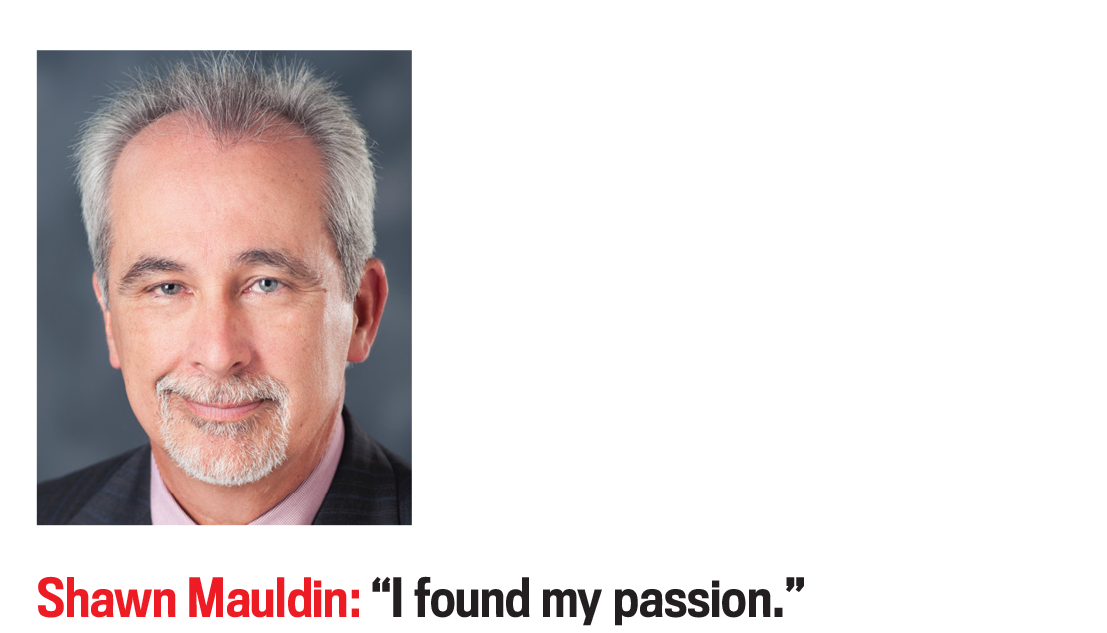

In 2015, Shawn Mauldin became director of the Adkerson School of Accountancy at Mississippi State University after having served as the dean of the College of Business at Nicholls State University in Louisiana. Mauldin’s professional accounting experience includes 12 years in various positions from staff accountant through chief financial officer. When asked why he chose to pursue a doctoral degree, he said, “I found my passion” while teaching for four years as a university instructor before entering the doctoral program at the University of Mississippi.

Like both Dickins and Honaker, Mauldin believes his background in accounting has served him well when working on research projects. “My professional work experience allowed me to draw on real-life experiences that were invaluable to me in the doctoral program. In fact, several papers that I wrote in the doctoral program were based on experiences I had while working. Personally, I think work experience should be a prerequisite to entering a doctoral program.”

After getting his degree in three years, Mauldin says that “Most of my research deals with ‘real world’ issues facing the accounting profession or accounting education.” His advice to others is, “I would recommend that they teach before entering a doctoral program and talk with faculty who have just entered the profession. They also need to understand that research is an important component to a career as an accounting educator.”

After more than seven years working in public accounting and industry, where he specialized in the internal audit function, Jared Soileau decided to join the traditional doctoral program at the University of Memphis. Even though he had no formal teaching experience at the university level, he had taught several Certified Internal Auditor (CIA) exam review courses and presented to students on numerous occasions. He eventually decided to enter the doctoral program to continue his education and “transfer knowledge through teaching and research without regret for not doing so.”

Soileau earned his doctorate in four years, during which his research agenda was guided by his interests in auditing, governance, risk management, and controls and how those topics relate to internal audit activities. His current research projects continue to focus on those same topics. Today, he’s an assistant professor at Louisiana State University, where he has taught Accounting Information Systems, Case Studies in Internal Auditing, and Governance Risk and Controls courses. While he’s happy with his academic career, he finds that he’s “juggling more projects than ever” and encounters “increased challenges with generational changes in today’s students.”

During his 18-year career, Rob Wilbanks worked in public accounting with a mid-sized local firm and a large regional firm, served as a corporate controller, and eventually worked for five years as CFO of a water utility. Having had a long-term personal goal of teaching at the university level, he taught accounting courses part-time for five years before entering the nontraditional doctoral program at Kennesaw State University. He chose the Kennesaw program because he thought its faculty and administrators might be more accepting of an older, nontraditional student than would be the case with a more traditional program.

“In addition, I thought that I would learn a great deal more from my fellow students in a DBA program than in a traditional Ph.D. program,” Wilbanks recalls. He graduated in four years and today is an assistant professor at Tennessee Technological University, where he teaches courses in Cost Accounting, Government and Not-for-Profit Accounting, and introductory classes in financial and managerial accounting. Wilbanks reports that “Students consistently indicate that they appreciate how I draw upon my industry experience to make the cost accounting concepts easier to understand.” He recommends that anyone with an interest in academia talk with an experienced academic about the profession in general and doctoral programs in particular. “Also, consider teaching a semester or two as an adjunct professor to see if you really have a calling to the profession.”

NEXT STEPS

It’s clear that there continues to be a critical need for qualified accountants to teach at the university level. If you’re seriously considering such a career change, contact professors in your IMA chapter or from your alma mater to talk about your hopes and concerns. A list of doctoral programs in accounting is available from the AACSB International (www.aacsb.edu/accreditation/accredited-members/global-listing). Another organization that accredits business programs in the U.S. and abroad is the Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs (ACBSP, www.acbsp.org). According to Diana Hallerud, an official with ACBSP, business programs it accredits tend to be associated with smaller and private (often faith-based) colleges and universities. At least three of its accredited member institutions offer doctoral programs in accounting.

An additional new wrinkle in accounting education is how graduate programs will have to adapt and adjust to the flood of new information technology and analytical tools that are constantly coming our way. For more on this topic, see “Accountants and Tech: A Game Changer?” in the March 2017 issue of Strategic Finance.

Are you ready to try a new career?

April 2017