Every firm is different. Executives need flexibility to discuss particulars of their own businesses. Writers using English have considerable latitude in how to tell their stories, but this storytelling must follow certain rules of spelling, grammar, and syntax. Executives using accounting to communicate with outsiders must similarly use agreed-upon rules for recognizing, valuing, and classifying accounts. Without this structure, financial statements lose their value to statement users and risk harmful decisions. Bad accounting means people get hurt, a painful lesson of Enron-era scandals.

I believe the use of non-GAAP income measures has crossed the line of propriety and now does more harm than good. Accounting practitioners and regulators need to get U.S.-listed businesses to stop using non-GAAP earnings and earnings per share (EPS) figures in company earnings releases. Failure to do so may bring a race to the bottom as companies use ever-more-aggressive accounting presentations to curry favor with investors and analysts. The unchecked use of non-GAAP measures risks significant harm to U.S. financial reporting.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The U.S. accounting environment is the most sophisticated in the world. Users of audited, GAAP-based financial statements take comfort that reported balances are generally comparable across companies. But the United States has struggled for a century to find agreed-upon ways to report financial performance. Getting to where we are today has been a bumpy road, and there is no easy way out of the current situation. If history is any guide, it will take considerable effort to rein in use of non-GAAP earnings.

Modern financial reporting emerged in the 19th Century as American railroad managers published financial information to persuade anxious British investors to support capital-intensive expansion in North America. Disclosure eased concerns of outsiders worried about getting their money back.

An early controversy was accounting for depreciation of equipment. Gradual wear and tear from rail activity degraded the earnings power of fixed assets. Most companies wrote off original costs when equipment was removed from service. Failure to provide for depreciation overstated periodic income and may have motivated railroad executives to favor dividend payments over capital reinvestment. Late investors who valued stocks on unsustainable dividend yields faced disappointment when the companies reduced dividends to fund needed capital expenditures.

In 1906, Congress passed the Hepburn Act to allow the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to regulate railroad rates and impose uniform accounting practices. Rules promulgated by the ICC required railroads to include a provision for depreciation on their income statements. Railroad executives pushed back, arguing that uniform accounting rules were unnecessary. The ICC dithered and chose not to enforce its regulations vigorously. Thus, the first attempt to standardize financial accounting failed.

Two other parts of the government expressed concern with American accounting conventions. In 1916, the Federal Trade Commission expressed dissatisfaction with diversity of accounting practices and perceived inadequacy of certain firms’ depreciation charges. The Federal Reserve also weighed in because member banks traded commercial paper issued by merchants and manufacturers. Banks relied on issuer balance sheets to assess credit risk. Inconsistent accounting could bring poor credit decisions and impair the health of the U.S. banking system.

Responding to calls for more uniformity, the American Institute of Accountants (which later joined another professional organization to create the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants or AICPA) formed the Committee on Accounting Procedure (CAP) in 1939 to narrow accounting differences. The first substantive pronouncement, Accounting Research Bulletin No. 2, addressed how a firm should account for unamortized discounts or premiums on bonds that are retired before maturity. The CAP was unable to select just one method out of three proposed accounting treatments.

Facing criticism, the AICPA tried again with the launch of the Accounting Principles Board (APB) in 1959. This replacement organization published opinions based on a more structured deliberation process. But the APB faced federal government interference. For example, the Board studied how to account for the investment tax credit introduced by the Kennedy administration and recommended spreading the tax benefit over the life of the acquired asset. Under political pressure, the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) intervened and said it would also accept financial statements using the alternate flow-through method, which provides a bigger boost to reported income in the year of a qualifying asset’s acquisition. The SEC, seeking to further the government’s political goal of supporting a fiscal stimulus, limited the APB’s ability to reduce diversity of accounting practice.

Eventual loss of confidence in the APB gave rise to the formation of the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in 1973. This independent organization received a healthy budget plus official recognition by the SEC as the financial accounting standard-setting body in the U.S. Whereas the CAP published suggestions and the APB promulgated recommendations, the FASB issues rules.

Yet continued government involvement has hampered the FASB’s efforts. To take one example, gas prices spiked after the 1973 oil embargo, and the U.S. sought to spur domestic oil production. Large oil companies used the successful efforts accounting method and charged dry hole exploration costs to income. Under this approach, smaller firms drilling fewer holes per year should expect to report earnings that are more volatile. Wildcatters sought to smooth earnings to compete for capital with larger firms, which were able to report more predictable income trends.

The entrepreneurs argued that dry holes are a necessary cost of discovering productive wells. Exploration charges, they believed, should be capitalized and expensed gradually. This second accounting treatment would presumably smooth income, facilitate the raising of capital, and support more drilling.

The FASB studied the issue and issued Statement 19 in 1977, which required oil and gas companies to use successful efforts accounting. Under pressure from lobbying efforts, the SEC issued Accounting Series Release 253 in 1978 to permit the use of full cost accounting. Once again, the government intervened in private-sector standard setting.

Politics continued to encumber the FASB’s efforts to narrow diversity of accounting practices. Debates over accounting for troubled debt restructuring, stock option compensation, and valuation of financial instruments demonstrated that standard setting is a messy, political process.

Establishing consensus is no simple task when tough accounting decisions result in winners and losers. We can’t pin blame on a particular group in government or industry and tell them to work harder. Accounting problems are societal problems. We’re all in this together.

A LOOK AT THE CURRENT STATE OF AFFAIRS

Though there still isn’t an agreed-upon set of uniform rules for reporting results, the good news is that practices have coalesced around a set of accepted principles. Public firms listed in the U.S. file financial statements based on GAAP. Users of filed statements have reasonable assurance that figures presented may be compared across companies. Such assurance breeds confidence in capital markets. No one believes GAAP are perfect. But analysts and investors do agree that use of standards is superior to the old, anything-goes Wild West environment.

Yet a new Wild West is emerging as companies increasingly report homegrown income measures in earnings releases that are published weeks before standardized SEC filings like GAAP-based quarterly 10-Q and annual 10-K statements become available.

This practice matters because people make decisions based on numbers provided in earnings releases. The problem isn’t that managers release earnings after closing the books—investors and others should have access to information on a timely basis—but that summary figures come from accounting rules that vary from company to company. While the market may see through disparate accounting treatments and get things right in aggregate, individual investors may be misled.

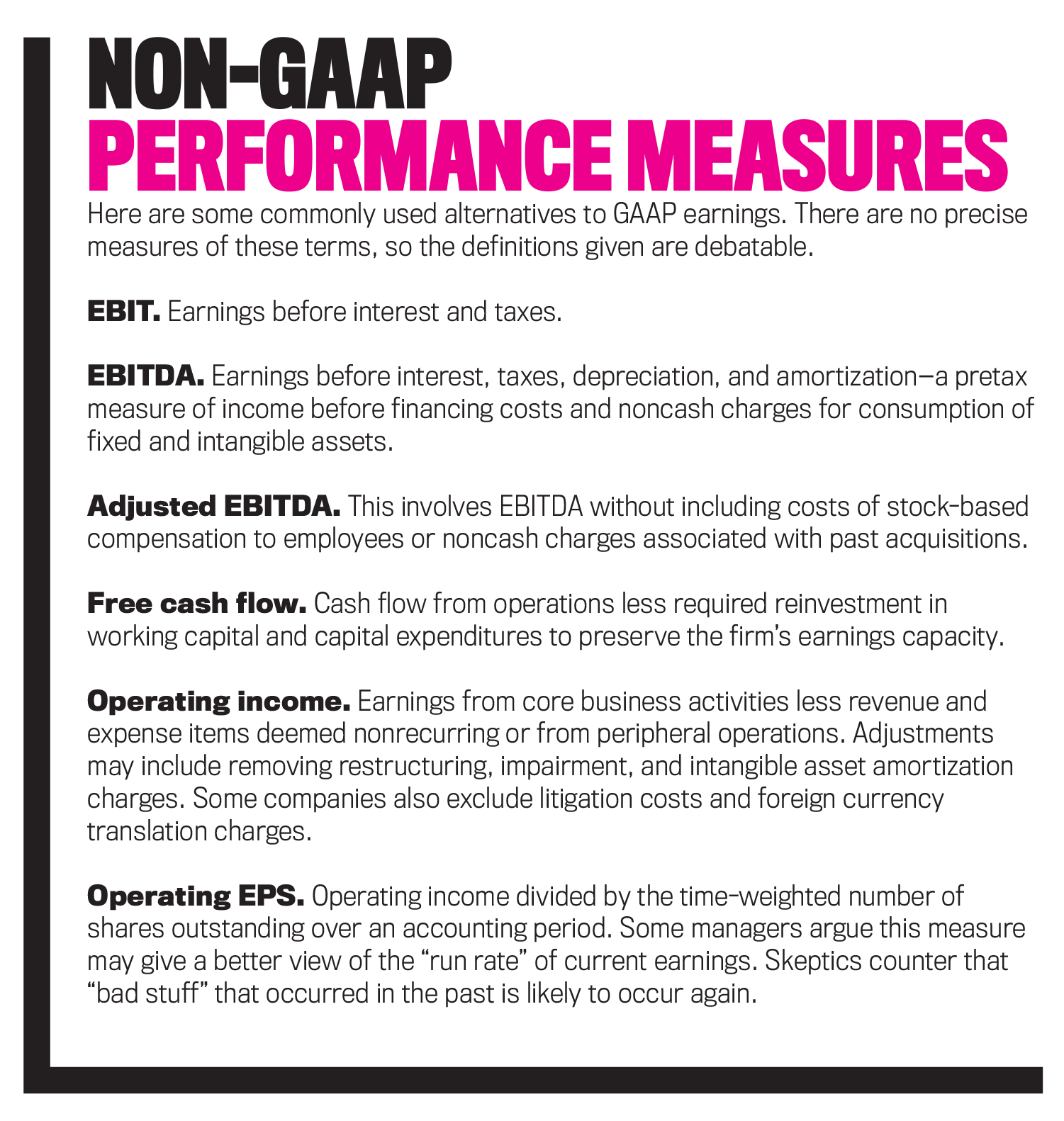

Non-GAAP (also called pro forma) figures help management teams assess proposed budgets or projects. These forward-looking analyses use company-specific approaches to recognize, value, and classify accounting balances. Modifications typically include efforts to remove sunk costs and add opportunity costs—accounting treatments that deviate from GAAP. Management teams understandably adjust balances in varied ways to suit particular circumstances. Since the intended audience is limited to those within the company, comparability across firms isn’t a concern.

Pro forma analyses typically try to estimate to a “run rate” of future cash flows. Common adjustments eliminate noncash expenses (e.g., stock-based compensation, amortization of intangible assets) and nonrecurring costs (e.g., restructuring or impairments charges). Financial statements based on GAAP, by contrast, show accruals and one-time costs to provide a more complete view of historical performance. By design, GAAP statements are messier because they include the hiccups and bumps every business experiences.

Companies may choose to disclose pro forma estimates to outsiders. Management teams that share non-GAAP earnings measures argue that these supplemental disclosures allow outsiders to better understand how management assesses recent performance and forecasts future business prospects.

Sound good? On January 24, 2001, Qwest Communications issued its earnings release for the quarter ended December 31, 2000. The document stated that on a “pro forma normalized basis and excluding non-recurring items,” EPS was $0.59, a 51% increase over the prior year. Qwest had “met or exceeded the consensus analysts’ estimate for the 15th consecutive quarter.” Nowhere in the release did the firm provide a GAAP net income figure.

Then on March 16, 2001, Qwest filed its 10-K and reported that GAAP EPS dropped from positive $1.52 in 1999 to negative $0.06. Management may have felt great about its accomplishments, but GAAP earnings hadn’t grown. They’d evaporated. Imagine the reaction you would have after purchasing stock on information provided in the January earnings release.

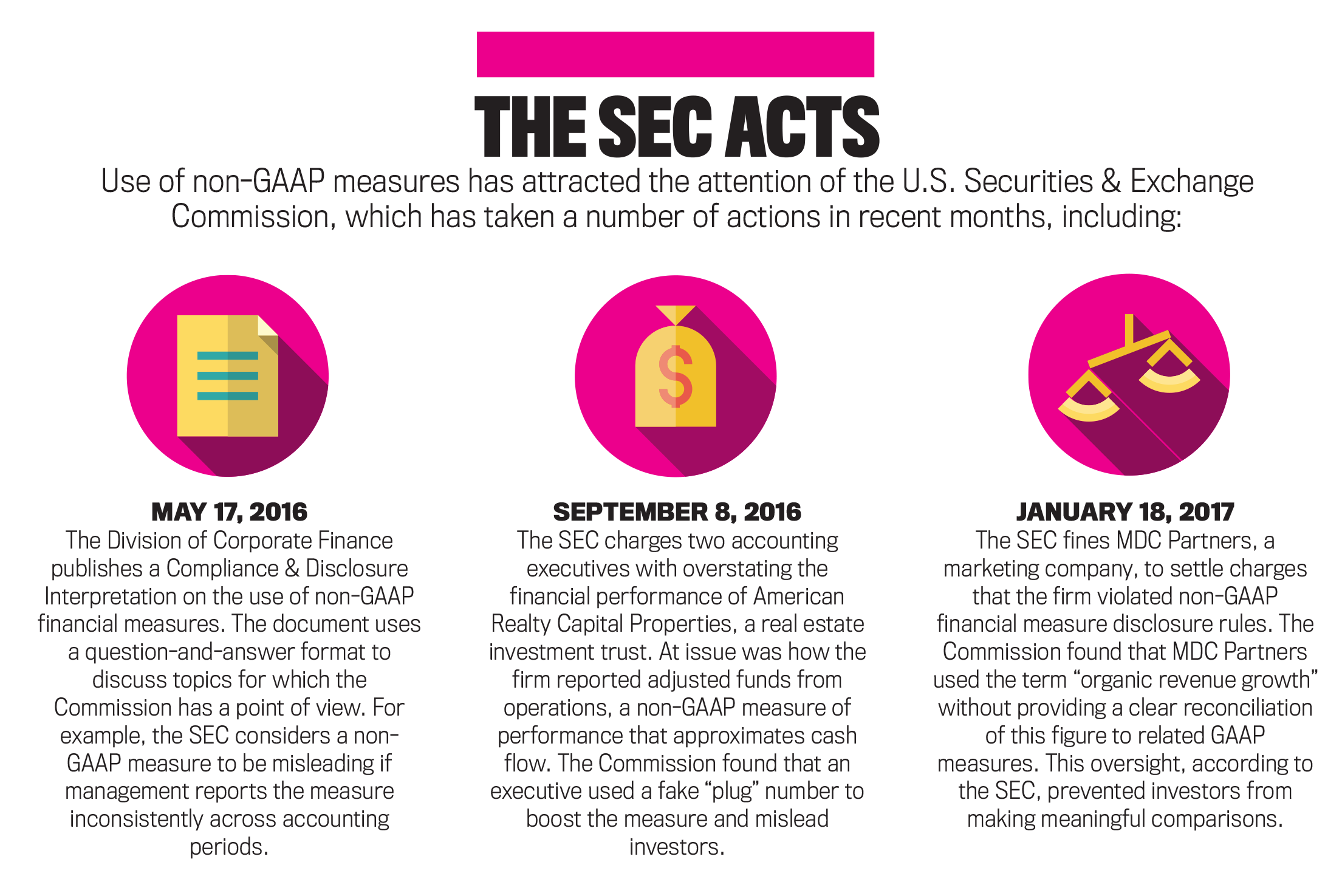

In response to these types of abuses, the SEC issued Regulation G in March 2003. Public companies must reconcile non-GAAP measures to comparable balances calculated under GAAP. This welcome rule doesn’t go far enough to improve comparisons across companies.

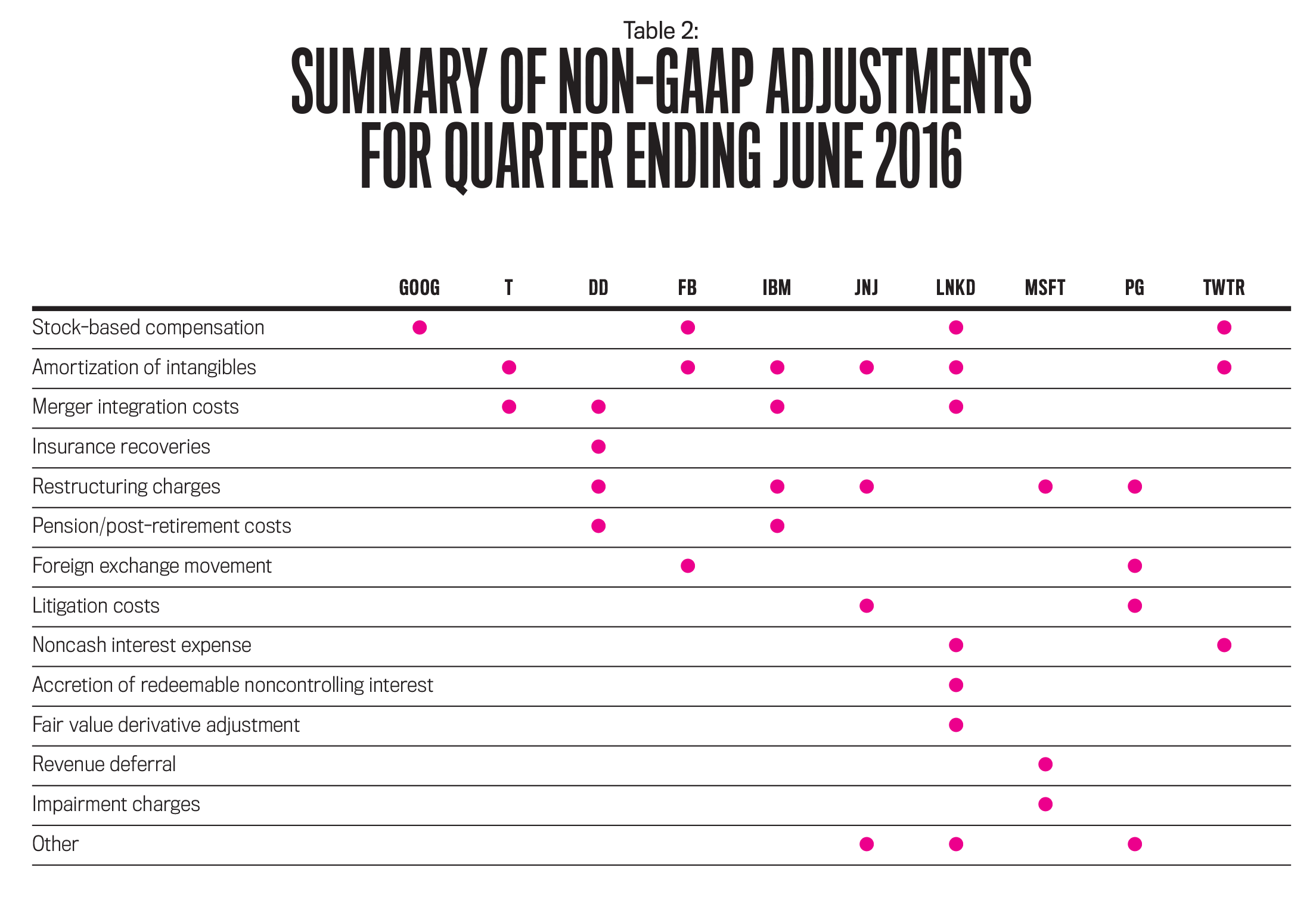

As evidence, consider Table 1, which summarizes earnings announcements for 10 public companies for the quarter ended June 2016. Presented are company name, stock symbol, quarterly EPS calculated using GAAP, non-GAAP EPS using whatever adjustments the company chose to make, and the difference between the two.

Click to enlarge.

The sample uses firms in varied industries and stages of the business life cycle. These aren’t penny stocks traded over the counter but well-known firms listed on leading exchanges. (LinkedIn entered into a merger agreement with Microsoft in June 2016, but they were independent companies at the time of these earnings releases.)

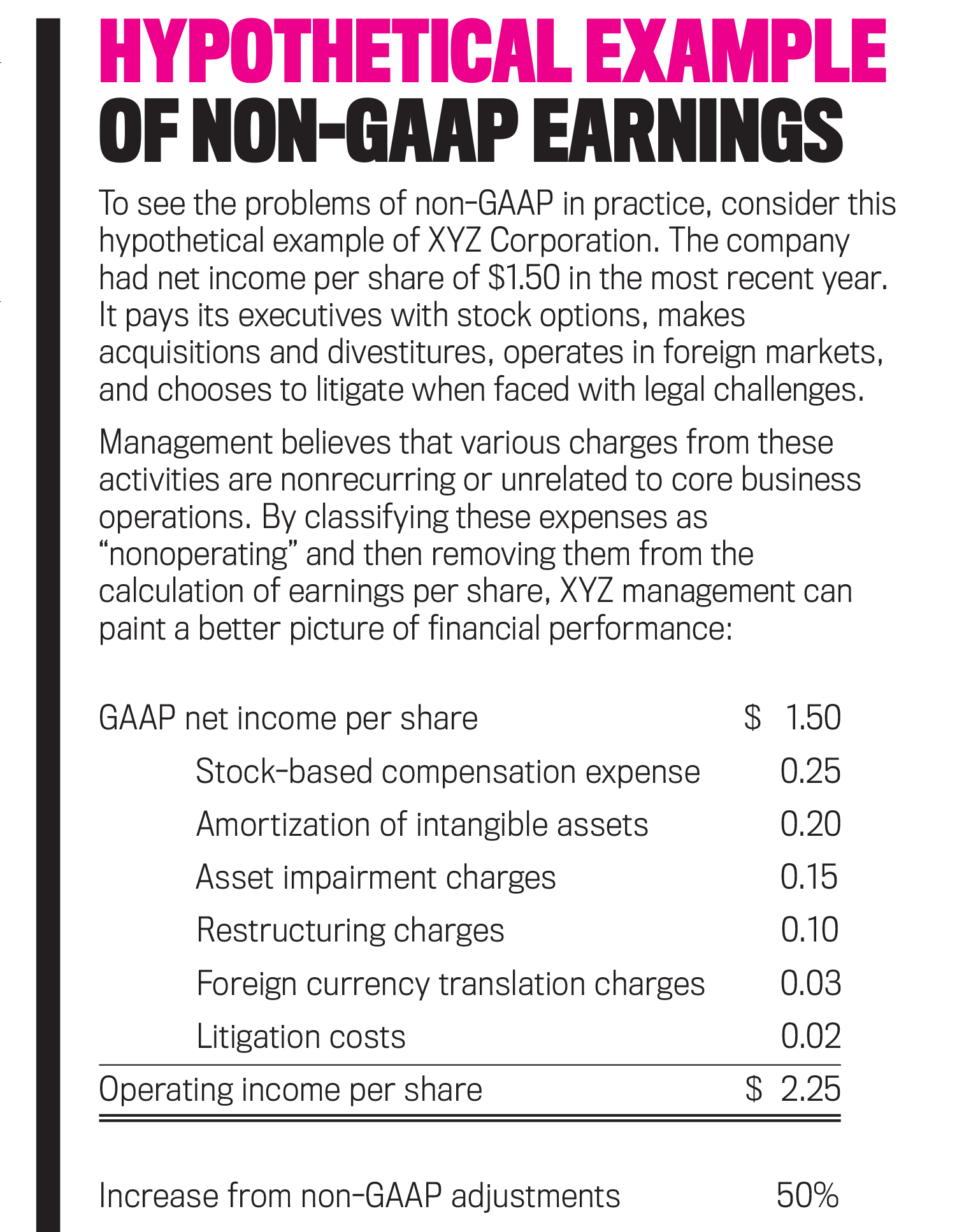

Note three things. First, the non-GAAP EPS figure is higher than that for the corresponding GAAP number for each company. It appears that companies use non-GAAP measures to burnish results. Second, each of the increases in reported income and reductions in losses is greater than 5%, an old-school benchmark used to assess whether a difference is material. So this isn’t about adjustments of a couple pennies per share.

Third, and most important, companies used varied adjustments to calculate non-GAAP earnings. Table 2 shows an attempt to compare these differences. The scatterplot reveals the absence of consistency in how companies calculate non-GAAP earnings. Sorting through the differences of just 10 companies for only one quarter was a difficult process. To use academic jargon, the exercise imposed a high cognitive load on this financial statement user. Now consider the potential problems with thousands of firms reporting earnings in different ways over many accounting periods.

Market participants understandably want to see a company report ever-increasing earnings. Consistent earnings growth brings rising stock prices and wealth creation. Broad acceptance of non-GAAP numbers is understandable when people believe that such activity will support increasing security values.

Now consider what happens if proliferation goes unchecked. Companies competing for capital will feel forced to expand use of non-GAAP measures to report increasingly favorable results, rationalizing that “my peers do it, so I have no choice.” An analogy is a few people standing up at a sporting event or concert to get a better view, blocking the vision of some spectators. Others follow suit to preserve their views. Soon, everyone is standing and no act of individual restraint brings any change in collective behavior. All fans now suffer a degraded viewing experience.

It isn’t a stretch to imagine that 5,000 U.S. public companies may eventually feel forced to use non-GAAP figures in earnings releases. If one company shows increasing earnings through use of homegrown measures, a competitor with flat GAAP-based figures may feel no choice but to follow suit. Others may then find increasingly clever ways to report progress for fear of falling behind.

A doomsday scenario is that the contagion spreads to accounting for balance sheet items, where executives feel the need to develop non-GAAP measures of cash, receivables, inventory, plant, intangible assets, payables, nonmonetary liabilities, and tax liabilities. If balance sheet validity degrades, we risk a complete collapse in the usefulness of all financial reports.

This scenario isn’t far-fetched. A study performed by watchdog organization Audit Analytics (see “One More Reason for Investors to Worry About ‘Earnings Before Bad Stuff,’” The Wall Street Journal, August 3, 2016) shows that aggressive use of non-GAAP earnings measures is associated with a higher incidence of company restatements.

Advocates of non-GAAP earnings may counter that standards don’t matter, saying the market sees through accounting treatments and gets valuations right. The problem is that no individual investor makes up the market. Market prices emerge from trading activities of self-interested participants. Should a few investors feel slighted, a marginalized minority could choose to disengage from investing. Should such feelings snowball, we risk the prospect of an increasing share of citizens choosing to sit out the capital-formation process necessary to sustain a prosperous economy. Preserving investor confidence lies at the heart of U.S. securities law.

If you don’t think we’re at risk, spend a half-hour listening to a financial talk show during earnings season. Commentators choose among at least six measures of performance to make period-over-period comparisons: current and prior period figures for GAAP earnings, non-GAAP earnings, and analyst consensus estimates for non-GAAP earnings. The resulting math means that it’s possible for pundits to provide nine comparisons.

Armed with so many data points, someone could tell a wide range of stories when summarizing company performance. Imagine how a few skeptical investors, listening to these discussions, begin to lose confidence in reported numbers. Consider then a future state where expanded use of non-GAAP measures includes revenue, margins, and balance-sheet items. It would be a complete mess.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

In July 2016, a group of business leaders including Warren Buffett, Jamie Dimon, and Jeffrey Immelt published an open letter calling for U.S. companies to adopt common sense corporate governance practices. Among the recommendations was that use of non-GAAP measures should be sensible and not used to obscure GAAP results (see here for the full list of principles).

A simple way to help implement this recommendation is to forbid SEC registrants from issuing non-GAAP earnings (or EPS) figures in corporate press releases. Firms would remain free to discuss non-GAAP performance measures in venues such as earnings conference calls, investor relations events, and industry conference presentations.

Using interactive forums gives outsiders the opportunity to ask managers why they chose to make deviations from GAAP. This dialogue would encourage managers to share how they think about alternate recognition, valuation, and classification choices when evaluating performance. Financial statement users could then follow up with questions to better understand the choices made by executive teams. Open-ended discussions would mitigate the likelihood of a business reporter simply grabbing and publishing a mushy non-GAAP figure.

A more deliberate dialogue between statement preparers and users would mitigate our current race to the bottom.

April 2017