But in some organizations, risk management and internal control (RM/IC) activities have deviated from their original purpose: to support management accountants and their business partners in setting and achieving their organization’s objectives. Instead, they have almost become objectives in their own right rather than serving as useful support tools. In addition, management accountants are often distracted by typical RM/IC compliance requirements that have little direct relation to their everyday work.

In this article, which is based on our personal experiences, we’ll provide insight and practical guidance on leveraging risk management as a benefit to our work, not a burden. We believe it’s time to recognize that:

- Our professionalism as management accountants is based on using our core competencies.

- Good risk management is good management accounting, not compliance, because risk affects our jobs and the achievement of our organizational objectives.

- Risk management becomes virtually invisible when it’s fully embedded in our core management accounting practices—it’s implicit in everything we do.

OUR CORE COMPETENCIES

Management

accountants facilitate sound objective setting and decision making, analyze and communicate operating results, and evaluate and drive business performance. We work in all types of organizations—large, small, public, private, nonprofit, and governmental. And we have a variety of titles, including financial analyst, reporting specialist, manager, controller, director, and CFO. In short, we are business partners and strategic advisors who focus on creating stakeholder value.

Successful management accountants have access to a full toolbox of core competencies, leveraging our relevant expertise as needed for a given challenge or situation. We also play a critical role in collaborative decision making, execution, and accountability processes. We collect, analyze, interpret, and provide information for decision making. In doing so, we help internal and external stakeholders understand and influence drivers of performance—and what might happen in the future under alternative scenarios—to ensure that our organizations make the best decisions and achieve their objectives.

Let’s take a look at management accountants’ core competencies as defined in the Content Specification Overview of the CMA® (Certified Management Accountant) exam:

Investment Decisions. This competency encompasses cash-flow estimates; discounted cash-flow concepts; net present value; internal rate of return, discounted payback; payback; income tax implications for investment decisions; risk analysis; and real options.

Planning, Budgeting, and Forecasting. This competency includes the strategic planning process; budgeting concepts; annual profit plans and supporting schedules; types of budgets, including activity-based budgeting, project budgeting, and flexible budgeting; top-level planning and analysis; and forecasting, including quantitative methods such as regression and learning-curve analysis.

Decision Analysis. This competency involves relevant data concepts; cost-volume-profit analysis; marginal analysis; make vs. buy decisions; income tax implications for operational decision analysis; pricing methodologies, including market comparables, cost-based approaches, and value-based approaches.

Cost Management. This competency addresses cost concepts, flows, and terminology; alternative cost objectives; cost measurement concepts; cost accumulation systems, including job-order costing, process costing, and activity-based costing (ABC); overhead cost allocation; supply chain management and business process performance topics such as Lean manufacturing, enterprise resource planning (ERP), Theory of Constraints, value chain analysis, activity-based management (ABM), continuous improvement, and efficient accounting processes.Corporate Finance. This competency encompasses types of risk, including credit, foreign exchange, interest rate, market, and political risk; capital instruments for long-term financing; initial and secondary public offerings; dividend policy; cost of capital; working capital management; raising capital; managing and financing working capital; mergers and acquisitions; and international finance.

Performance Management. This competency addresses the factors to be analyzed for control and performance evaluation, including revenues, costs, profits, and investment in assets; variance analysis based on flexible budgets and standard costs; responsibility accounting for revenue, cost, contribution, and profit centers; key performance indicators; and the balanced scorecard.

External Financial Reporting Decisions. This competency covers the preparation of financial statements (balance sheet, income statement, statement of changes in equity, and statement of cash flows); valuation of assets and liabilities; operating and capital leases; impact of equity transactions; revenue recognition; income measurement; and major differences between U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

Financial Statement Analysis. This competency involves the calculation and interpretation of financial ratios; performance evaluation utilizing multiple ratios; market value vs. book value; profitability analysis; analytical issues, including the impact of foreign operations, effects of changing prices and inflation, off-balance-sheet financing, and earnings quality.

Each of these core management accounting competencies focuses on enabling sound decision making and, as such, represents pure risk management activities.

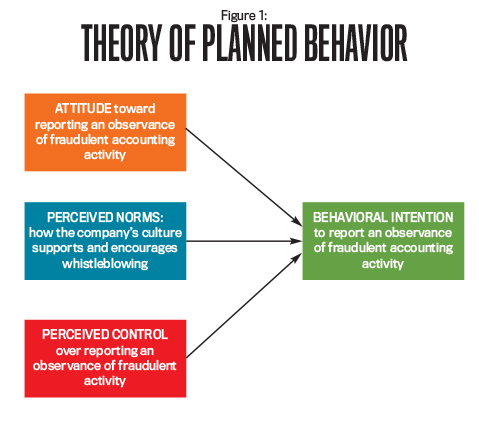

The Content Specification Overview also identifies three overarching competencies that are fundamental and integral to all the other competencies just described—Professional Ethics, Risk Management, and Internal Control. Thus risk management is both implicit throughout the management accountant’s core technical competencies and explicitly identified as an overarching competency. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of the management accountant’s core competencies.

FROM BOLT-ON TO BUILT-IN

Few people come to work each day with the intention to actively manage risk. Rather, the typical person’s intent is to get the job or tasks done properly and thereby achieve the desired objectives. And this is how it should be. After all, an organization’s main objective is not to effectively manage risk nor to have effective controls, but to properly set and achieve its goals.

Yet some organizations have tried to implement formal enterprise risk management (ERM) systems in which the management of risk has become an objective in itself. Such systems often oblige people to periodically jump through a series of formal risk management hoops, including participation in formal “risk sessions.” The following five steps may sound all too familiar:

- Identify the risks to the organization via formal risk sessions;

- Assess the identified risks in order of impact and likelihood;

- Capture the key risks in a risk register so that the risk manager can

- Mitigate and actively monitor them and then

- Disclose them in the annual report.

Typically, such risk sessions are very inefficient and arguably are even the wrong way around.

The sessions are inefficient because trying to identify all risks out there is an enormous task. Basically, you can put the word “risk” behind every noun and create a new risk category—for example, “project risk,” “liquidity risk,” “interest risk,” “compliance risk,” and on and on and on. This exercise typically leads to a plethora of risks, mostly with an unclear or far-fetched linkage and little relevance to the objectives they might affect. And only a fraction of them are truly relevant.

The risk sessions are the wrong way around because the starting point should be what it is we want to achieve. Then, in that light, we should identify the range of things that might better enable us to get there or prevent us from doing so. Of course, once we’re on the way to achieving our objectives, we should continually monitor developments in the internal or external environment that might give rise to changes in our risk assessment. But this also should be done in light of our objectives.

Not only are these stand-alone, or bolt-on, exercises often poorly aligned with setting and achieving the organization’s objectives, but they also typically remove responsibility for the management of risk from where it primarily belongs: incorporated into line management as a natural part of, or built-into, the regular organizational management processes, not as a separate risk management function. In short, those people responsible for setting and achieving certain organizational objectives are automatically also responsible for managing the related risk. These two responsibilities can’t and shouldn’t be separated.

How does all this affect us as management accountants? We have a lot in common with everyone else in our organization. We want to get our job done and, by leveraging our core competencies described earlier, support our organization in properly setting and achieving its objectives. And we don’t like to be distracted by an imposed risk management exercise that has little relevance to our daily activities in order to stay in compliance with internal policies and/or external regulations. On the other hand, we face uncertainties in all our management accounting activities, both opportunities and threats that could affect achievement of our organization’s objectives. The sources of these uncertainties are inside (culture, systems, processes, etc.) and outside our organization, for example Michael Porter’s Five Forces of Competition (suppliers, competitors, new entrants, substitutes, and buyers), and can be political, economic, social, technological, legal, or environmental (PESTLE). Actively managing those uncertainties, i.e., managing risk to our objectives, would certainly be a smart thing to do!

The good news, and our key message, is that effective risk management is typically, or at least should be, an integral (built-in) part of our regular management accounting activities:

- Good decisions and actions are underpinned by sound decision making, which equals good risk management.

- Management accounting, using our core competences as described earlier, enables sound decision making.

- Therefore, good management accounting is good risk management!

The brief descriptions of the core management accounting competencies clearly demonstrate that these management accounting activities are pure risk management activities.

THE DECISION-MAKING & EXECUTION WHEEL

Integrating risk management means adopting ways to influence the managerial processes that already exist, enhancing and improving them but not necessarily replacing or increasing them. To that end, we have to work from the inside out by first understanding how decisions are made and executed and then determining how managing risk should be integrated into those decisions.

One tool that can help is the Decision-Making & Execution Wheel (see Figure 2). It’s a simple representation of an organization’s system of management based on universal managerial planning and control activities. In practice, many of the activities in these steps will be executed intuitively. But good intuitive decisions and actions are underpinned by sound decision making—asking and answering the right questions—which equals good risk management.

Using the Decision-Making & Execution Wheel, here are some typical questions for consideration as you move through the various steps of a decision or initiative:

A. Preparing before making a decision—What do we want to achieve, and how do we go about making the right decision?

B. Decision making—What things might better enable us to achieve, or prevent us from achieving, our intended outcomes, and what would be their effect?

C. Acting after the decision—What should be done by whom, including establishing control, to execute the decision appropriately?

D. Monitoring and reviewing—Are we still progressing according to plan? Do changes in the environment give rise to new risks? Are controls still effective?

E. Learning—Did we achieve our intended outcomes? What went right, and what went wrong? What should we do differently next time?

The decision wheel and underlying questions don’t serve as a checklist. Rather, they demonstrate how risk can be managed as an integral part of managing an organization (i.e., built-in) and aligned with the main objective of an organization, which is to make the best possible decisions and to achieve its objectives appropriately.

Achieving an organization’s objectives usually requires going through multiple planning and control cycles, each with its own lead time. From long-term strategic planning via tactical changes of direction to short-term operational tweaks, one of the most critical phases from a risk management perspective is strategic decision making. Launching a new product or service, for example, can lead to a wide range of outcomes, some with a low probability of occurrence but with major positive or negative consequences. Such uncertainties need to be considered very carefully.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have to deal with many operational issues, such as fluctuations in resource pricing, availability of specialized staff, or creditworthiness of our customers. Any given operational issue may be individually small. But if it occurs frequently or there are many small issues, together they may account for a large portion of overall risk. Therefore, handling these uncertainties also needs careful consideration, but typically in a shorter interval and in a more organized way than dealing with high-level risk.

Finally, even though we might be consumed by day-to-day operations, we should periodically reserve time to sit back and look at the bigger picture once more. How are we doing (strengths and weaknesses), what has changed in the environment (new opportunities and threats), and what does that mean for our objectives? Consistently going through all the steps of all the cycles greatly improves our planning and control capacity, thereby increasing our chances of success.

The recent International Federation of Accountants® (IFAC®) thought paper, From Bolt-on to Built-in—Managing Risk as an Integral Part of an Organization (bit.ly/2bJUoFm), further explores the benefits of properly integrating the management of risk and provides ideas and suggestions on how to achieve such integration. The following case study specifically shows how our core management accounting activities actively support our organization, solving the issues at hand along the steps of the Decision-Making & Execution Wheel. As such, it demonstrates that risk management is what we already do automatically when we apply our management accounting competencies appropriately.

SUSTAINABILITY: A CASE STUDY

For many companies around the world, considering their environmental footprint is no longer an option—it’s a corporate imperative. Fortunately, doing so can often have a positive impact on the bottom line. Therefore, many companies are now defining aggressive, long-range environmental impact goals accordingly.

Within this context, the company in our case study announced a series of 2020 environmental sustainability destination goals detailing how it planned to cut its environmental footprint by half. In conjunction with these goals, the company expects to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50%, including sourcing at least 40% of its electricity requirement from renewable sources. For the company to realize its overall goals, its largest operation obviously must play a key role.

Historically, the company’s premier operation has met its energy needs by leveraging a mix of coal, natural gas, and #6 oil boilers to create steam along with purchasing electricity off the local grid. Coal is the site’s lowest-cost energy source for the boilers. More recently, though, there have been regulatory signals that coal boiler owners may soon face costly new pollution control requirements. And the boilers are now more than 50 years old, so they require more frequent and costly maintenance each year. Indeed, one of the site’s two coal boilers had an unexpected failure, and it will require $1 million or more to repair. As such, local management has been charged with developing a long-term fuel sourcing strategy.

In this case study, those responsible for setting and achieving our organization’s objectives are also responsible for effectively managing the related risk. As defining strategy and setting objectives are often the activities that involve the most risk, we don’t want to wait until after we’ve established our objectives. Instead, we want to ensure that risk management is an integral part of our decision-making process to set our objectives.

For that reason, you have been asked, as the site’s financial executive, to provide recommendations for the boiler strategy, including supporting analyses. The main questions are: Should management invest $1 million or more to repair the coal boiler that’s down? Should management even continue using coal as a long-term fuel source? What alternatives should be considered, and what are the pros and cons of each? What additional information would be needed for making a well-informed decision? Finally, what management accountant core competencies are relevant for working through this strategic decision-making process?

While developing its long-term fuel sourcing strategy for the boilers, management is approached by a third party that would like to partner with the company in making renewable electric investments. Specifically, the third party would like to enter long-term agreements whereby it invests in and operates wind farm, solar field, and/or biogas facilities while the company agrees to purchase any electricity generated by these facilities.

Again, you’ve been asked to make recommendations on each of the proposed renewable electric initiatives: Should management move forward with the wind farm, solar field, and/or biogas initiatives? Why or why not? What should be considered in the purchase power agreement (PPA) and/or related agreements? What additional information would be helpful in making your recommendations? And what core competencies are most relevant from the management accountant’s toolbox to support you?

Leveraging the management accounting core competencies and the Decision-Making & Execution Wheel, you can help our organization to:

- Focus primarily on setting and achieving objectives to create sustainable value and growth.

- Identify, assess, treat, report, monitor, and review risk in relation to the objectives management wants to achieve while giving consideration to an ever-changing context.

- Ensure that all decisions to be made, both big and small, are informed by an appropriate assessment of related risk.

- Provide high-quality information that’s crucial to good decision making because it reduces uncertainty.

- Enable effective management of risk in all managerial steps following the decision-making process.

- Keep our organization sufficiently resilient and agile in all its activities to adequately respond to changes in circumstances and deal with the consequences of unforeseen events.

This case study demonstrates that, by applying the core management accounting competencies, we can assist our organizations in making informed decisions about what management wants to achieve; realizing these objectives while complying with legal, regulatory, and societal expectations; and responding and adapting to surprises, disruptions, and changes in the environment along the way.

HELP MANAGE RISK

As management accountants, we are business partners and strategic advisors. We benefit from a full toolbox of core competencies. And we know that good risk management is good management accounting because good risk management enables us to achieve our organizational objectives and deliver stakeholder value.

To that end, we challenge you to fully integrate risk management into your daily management accounting activities. It’s what we do!

STEVE’S JOURNEY

As is the case with so many management accountants, my previous exposure to the COSO (Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission) Framework was in the context of internal control over external financial reporting, specifically for purposes of compliance with the U.S. Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX).

But I had an epiphany while representing IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) on the COSO Advisory Council charged with updating the original 1992 Internal Control—Integrated Framework, which resulted in COSO’s release of the updated Framework in May 2013. The lightbulb went on that effective internal controls can benefit the achievement of operational objectives as well.

It has taken even more time for me to realize, though, that creating and maintaining an effective system of internal control isn’t the point. Identifying and managing risk isn’t the point either. Rather, we should be focused on defining our organizations’ strategic goals and objectives, then doing what it takes to achieve them.

For example, your CEO may articulate a vision to significantly reduce your company’s carbon footprint. To realize this vision, your company’s premier manufacturing facility likely will need to take the lead. Surely management will need to do some things differently, probably making several large investments along the way.

And we management accountants can play a leading role in all of this. Through our core competencies, we know how to identify both opportunities and threats, ask the right questions, and drive decisions.

And, yes, leveraging risk management and internal control also plays a role. But RM/IC becomes a benefit, not a burden. It’s what we do!

VINCENT’S JOURNEY

Working in an accounting environment in the 1990s, I noticed that many organizations were implementing various management systems to deal with different aspects of their business processes, such as governance, risk management, and internal control (GRC or RM/IC), and health, safety, environment, and quality.

Often, different parts of the organization developed these systems next to, and in isolation from, each other—with each using its own type of internal or external specialists.

Then I realized that organizations can’t produce first and think about opportunities and risk, health, safety, environment, and quality only as an afterthought. Nor can they manage them through separate systems. Instead, all these aspects need to be addressed up-front and head-on and managed as integral parts of the organization’s overall system of management.

This became the business philosophy of INTE-Q Integration Management, the small Dutch consulting firm that I as a management accountant, founded together with a biologist, a physical geographer, a lawyer, and a pharmacist.

My subsequent journey through numerous engagements and other experiences, such as working with management accountants from across the world through IFAC’s Professional Accountants in Business Committee, has only reinforced the necessity of an integrated approach.

It also taught me that when we, as management accountants, are doing our job correctly, all these aspects are already automatically integrated. Risk and internal control is what we already do!

Copyright © September 2016 by IFAC and IMA. All rights reserved. Written permission is required to reproduce, store or transmit, or to make other similar uses of this document. Contact permissions@ifac.org or aschulman@imanet.org.

September 2016