The In-Plan ROTH rollover (IP rollover) provisions in Internal Revenue Code §402A(c)(4) provide employees, regardless of age, the ability to move their pretax retirement funds into a designated Roth account within their company’s retirement plan. An employee is allowed to make IP rollovers if the retirement plan—401(k), 403(b), or 457(b)—includes a qualified Roth account that permits IP rollovers. Only vested retirement funds qualify to be rolled over. Retirement plan providers have a great deal of flexibility with respect to what types of vested retirement funds (qualified, elective, nonelective, matching, after-tax, and rollover funds from another plan) are allowed to be rolled over and how often an IP rollover can occur. Therefore, a taxpayer who is considering an IP rollover should check with the plan’s representatives for details.

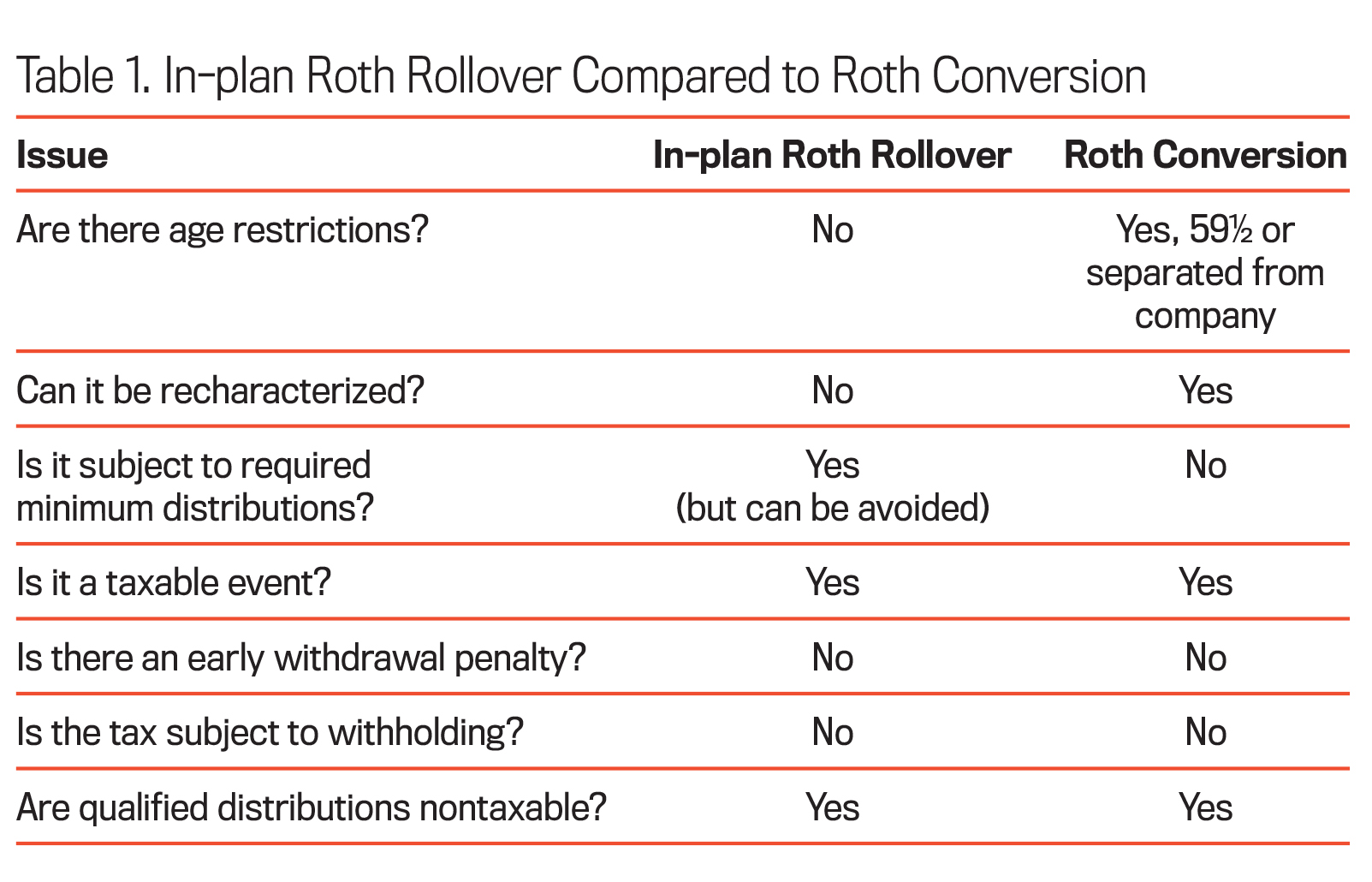

An IP rollover is similar to a Roth conversion of retirement assets (conversion), with some important differences. A conversion moves retirement funds to a Roth IRA account outside the retirement plan. An IP rollover (sometimes called an in-plan Roth conversion) involves moving pretax retirement funds to a designated Roth account within the retirement plan. Table 1 compares tax issues related to an IP rollover and a Roth conversion.

The first three items on the table represent the major differences between an IP rollover and a Roth conversion. First, a Roth conversion from an employer plan is only available to taxpayers who are at least 59½ years old or who are separated from the company. This is a significant advantage for the IP rollover, which, as mentioned earlier, is allowed for employees regardless of their age. The ability to perform the rollover at a younger age provides taxpayers more years of tax-free earnings. The compounding of tax-free earnings over a longer period of time substantially increases a taxpayer’s retirement assets. In addition, younger taxpayers can now roll over their retirement funds into an in-plan Roth account at a time when they are likely to be in a lower income tax bracket.

Second, an IP rollover isn’t allowed to be recharacterized. This is a major disadvantage. Roth conversions can be canceled up to 18 months after they occur, which can protect the taxpayer from post-conversion declines in value. The taxpayer can reconvert the lower value after the start of the post-conversion taxable period or 30 days, whichever is longer. The ability to convert, recharacterize, and then reconvert can result in substantial tax savings. Some taxpayers perform multiple conversions annually, with plans of recharacterizing most of the conversions while retaining those that increase in value the most.

Third, Roth retirement plan accounts from IP rollovers are subject to required minimum distributions (RMDs), while Roth IRA accounts outside a retirement plan, i.e., from conversions, are not. This could be a significant disadvantage. RMDs limit a taxpayer’s ability to manage yearly taxable income and flexibility for estate planning. When one spouse passes away, distributions continue to be made to a single surviving spouse. Assuming all other taxpayer variables remain the same, filing as a single taxpayer would likely result in being taxed at a higher rate. Furthermore, the tax on a taxpayer’s Social Security income could increase due to the added income from the RMDs. Alternately, a taxpayer can choose when, if at all, to start withdrawing from a Roth IRA account. If the taxpayer has enough income from other sources to fund the retirement years, the Roth IRA account can be directly transferred to heirs, who can choose to continue the tax-free attribute of the Roth IRA throughout their lifetime.

The RMD requirement for a designated Roth account within a retirement plan can be avoided by rolling over the in-plan Roth funds to a regular Roth IRA account outside the retirement plan after the employee leaves the company but before he or she turns 70½ years old. Taxpayers who don’t already have a Roth IRA account outside a retirement plan may be subject to a new five-year holding period.

The tax consequences of the last four issues on the table are generally the same for both IP rollovers and conversions. Both are taxable events. The taxable amount is equal to the amount of the IP rollover or conversion minus the tax basis of the retirement funds. For example, any after-tax employee contributions wouldn’t be subject to taxation. Also, while both an IP rollover and conversion are taxable events, neither will be subject to the 10% early withdrawal penalty. In addition, withholding requirements don’t apply to IP rollovers or conversions. Consequently, taxpayers should plan accordingly for the additional tax liability by increasing their withholdings or making estimated tax payments. Last, qualified distributions from both IP rollovers and conversions, i.e., those made after the required five-year period by taxpayers who are at least 59½ years old, are generally nontaxable.

Taxpayers can reduce the total IP rollover tax by using a multiyear IP rollover plan. This will spread the additional taxable income over more than one year. For example, assume a taxpayer wants to roll over $100,000 of pretaxed retirement funds. Instead of performing a single IP rollover of the entire $100,000, the taxpayer can roll over $25,000 each year for four years. This will likely reduce the total IP rollover tax by preventing the taxpayer’s marginal tax rate from being pushed into a higher tax bracket(s). In addition, it makes the IP rollover tax payments more manageable. This is especially helpful for younger taxpayers who are less likely to have substantial after-tax funds.

© 2016 A.P. Curatola

September 2016