One exciting new venture is the Women’s Accounting Leadership Series (WALS), a continuing education event designed for women in accounting and finance. Cosponsored by IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) and Pace University, the series has been offered four times in the past two years in New York, Ohio, and Arizona. WALS brings together women in accounting and finance with varying years of experience from different industries for a discussion about careers and technical issues in accounting. The setting provides a forum for women to share thoughts regarding their own leadership development and strategies for success.

The event begins with a presentation and conversation focused on basic metrics related to leadership in accounting and finance. Many of the WALS participants have been surprised to learn about the slow progress in the number of women reaching influential leadership roles such as board member and CEO, CFO, or other C-suite positions. Next, we have an update about a technical accounting topic and a panel session on strategies for professional success. Then participants discuss their personal experiences and offer advice on dealing with issues in the workplace.

Yet WALS is only one initiative. Let’s also look at some statistics that describe how women have been represented in a range of finance and accounting leadership roles over the past few decades.

FOCUSING THE CONVERSATION

Many studies suggest that organizations with gender diversity in leadership perform better on several levels compared to those with low diversity among the C-suite or board of directors. In addition, a variety of leading companies have strategically prioritized their diversity and inclusion initiatives by putting them front and center with their top strategic goals. But the focus of this article is gender diversity in accounting and finance leadership—it isn’t intended to minimize the importance of many other types of diversity that contribute to the total equation of an inclusive environment. I’ll start with a look at trends and key facts related to the number of women in the boardroom, C-suite, CFO role, overall workforce, and educational pipeline. Then I’ll share some compensation challenges and describe the WALS conversations on building leadership capacity and setting the stage for future progress.

PERFORMANCE IMPACT OF WOMEN ON THE BOARD

The impact of a diverse board of directors on corporate performance is widely cited as significant. Globally, there are many initiatives at leading companies that are aimed at increasing the percentage of women on their boards. One is to obtain 20% female board membership by 2020. In fact, an initiative called 2020 Women on Boards is tracking this very progress! A similar group called the Thirty Percent Coalition has comparable goals. Both groups report positive results with their trends but emphasize there’s much work to be done.

In addition, countries such as Norway, Germany, France, and Spain have implemented quotas to ensure a certain percentage of women board members. But there are cons to using quotas, so it will be important for all types of leaders to monitor these initiatives to assess the impact and achievement of desired outcomes. All professionals must be aware of and understand the progress and initiatives related to boardroom diversity, and WALS participants said they found it insightful to learn more about trends affecting the percentage of women on boards.

During the conversations at each WALS workshop, attendees asked, “Does it really make a difference in terms of organizational performance if there are more women on the board?” The answer depends on several factors, but some well-cited studies indicate a clear “yes.” For example, a study by Catalyst, “The Bottom Line: Corporate Performance and Women’s Representation on Boards,” notes that return on equity was at least 53% higher for companies with the greatest percentage of women board members. The study also found positive performance indicators for boards that have at least three women directors. Achieving a level of three women on the board seems to be a common goal for many boards and is often referred to as the “power of three.” Since the average size of a publicly traded company’s board is often 10-12 board members, three women directors could easily lead to helping the board achieve a goal of 25%-33% female leadership. Obtaining this percentage may not seem significant, but it could be difficult for many global boards to attain in the next several years based on the progress so far. In its “2015 CDWI Report on Women Directors of Fortune Global 200: 2004-2014,” Corporate Women Directors International reported that the number of women board directors globally has increased by only 7.4% in the decade from 2004 when it was 10.4% to a reported 17.8% in 2014. Perhaps reaching 20% by 2020 isn’t too unrealistic.

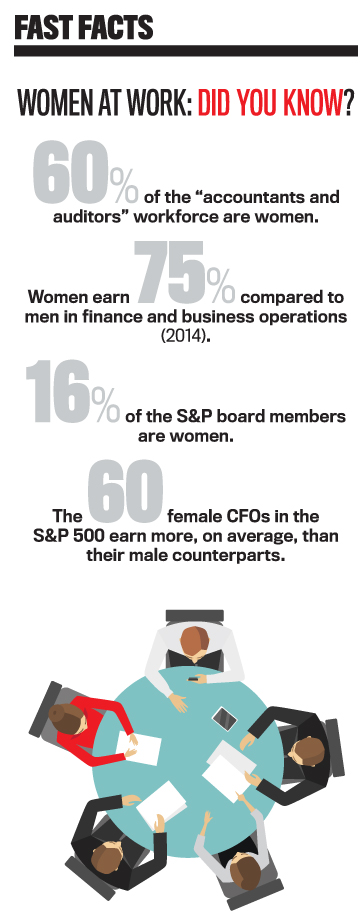

A recent study by EY, “Women on US boards: What are we seeing?” reports similar results, with women representing 16% of board membership for the S&P 500. In addition, the report indicated that about 67% of smaller publicly traded companies have at least one woman on their board. This still leaves about one-third of the smaller companies with no women on their board, and, based on the track record from the past decade, it may be a slow process for notable increases for smaller or private companies.

PERFORMANCE IMPACT OF WOMEN IN THE C-SUITE

Moving from the board to the C-suite, a February 2016 global study by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) and EY, “Is Gender Diversity Profitable? Evidence from a Global Survey,” examined more than 20,000 publicly traded companies in 91 countries. It found that organizations with women in at least 30% of C-suite or similar corporate leadership roles may expect to add more than one percentage point to their net margin compared to organizations with no women leaders. This may not seem like a lot, but in the sample used in the study, the typical profitable firm had a net profit margin of 6.4%, so a 1% difference represents a positive 15% impact on profitability.

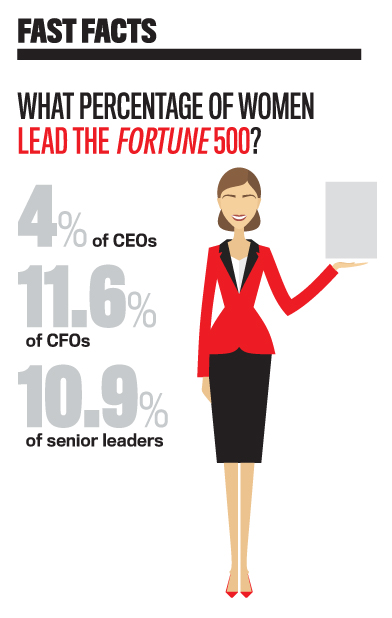

In March, Fortune magazine reported that only 10.9% of Fortune 500 senior leaders are female and that slightly more than one-third of these organizations have no women in the C-suite. The numbers for the top of the C-suite in the United States are much lower, with women representing only 4% of Fortune 500 CEOs. (See the Fortune article, “The Most Reputable Companies Have More Women in the C-Suite, Study Finds.”)

WOMEN LEADING IN ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE

What about women in accounting and finance leadership roles? A quick glance at Fortune 500 companies shows that nearly 90% of CFOs are men. Fortune reports that, in 2015, women held 11.6% (58) of CFO positions in Fortune 500 organizations (see “58 women CFOs in the Fortune 500: Is this progress?”). Compared to the fact that less than 5% of CEOs are women, the CFO percentages may seem like good news, but it’s important to take a wider look at the last 15 years where the trend paints a different picture. In 2000, Catalyst reported that 5.6% (28) of America’s largest companies had women CFOs and, in 2002, 7.1% (36). This means a move of about six percentage points, or an increase of 30 women in the CFO role, has occurred since the beginning of the 21st Century. Is this adequate movement? Let’s take a deeper look into the overall workforce from the past few decades.

A glance at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data on the accounting and finance workforce shows important results based on the analysis of two key categories. In 2015, the BLS reported that in the category Accountants and Auditors, the workforce size is about 1.7 million, of which 60% are women. Because many leaders in accounting and finance hold positions that have the word finance or financial in the position title, it’s also important to consider additional categories. The BLS category representing positions classified as Financial Analysts indicates that only 43% of the workforce of 322,000 consists of women. For purposes of the WALS discussion, both categories help create a further understanding of the pool of available talent.

ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE EDUCATIONAL PIPELINE

The previous metrics indicate slow progress in women’s leadership at the board, CEO, C-suite, and CFO levels in a variety of ways. Is this because the pool is too small? The BLS data suggests that there’s a healthy number in the workforce. Some people might argue that there haven’t been enough women in the pipeline long enough to evolve into the senior-level accounting and finance roles. Perhaps that’s the case in some industries, but a closer look at the educational pipeline over the past few decades may provide a clear picture.

In the U.S., the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reports that women earned about 46% of all bachelor’s degrees in 1976. By 1982, they were earning more than 50% of all bachelor’s degrees. And since the late 1990s, that percentage has grown to about 57%.

These numbers indicate that women have earned more bachelor’s degrees than men have for the past 30 years, but are they the right types of degrees? Looking back 25 years, the NCES reports that women earned 47% of business bachelor’s degrees, 54% of accounting degrees, and 32% of finance degrees. Data wasn’t available in the same format for earlier years, but it probably wasn’t dramatically different in the previous five and perhaps even 10 years based on the number of degrees earned by women throughout the 1980s. With a solid pipeline of women educated in accounting and finance over the past 25 to 30 years, is it reasonable to expect that the percentages of women in key leadership roles would be higher? Do we really have a pipeline problem? There are many other factors that must be considered, and WALS participants found it helpful to look a bit deeper into the rates of women earning advanced degrees.

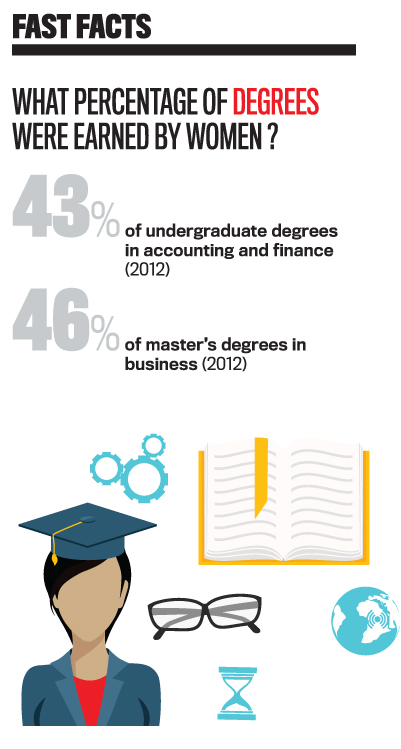

How has the pipeline been fueled recently? The NCES indicates that in academic year 2012-2013, close to 50,000 undergraduate degrees were conferred in accounting, and women earned 52% of them. In addition, approximately 31,000 undergraduate degrees were conferred in finance, and women earned 30% of those. This means women earned about 43% of the 81,000 undergraduate degrees in accounting and finance. The NCES covers other, much smaller categories linked to accounting or finance functions, but the accounting and finance categories represent positions that are aligned more closely with a potential path to CFO. In addition, MBA degrees represent a common CFO path. Since 1986, women have earned at least one-third of all master’s degrees in business, the majority MBAs. In 2012, women earned about 46% of all master’s degrees in business.

While the pipeline looks strong on many dimensions, the number of bachelor’s degrees in accounting earned by women over the last decade has decreased. In 2003-2004, the NCES reported that women earned 61% of accounting degrees and 35% of finance degrees.

Role models in the educational pipeline are also important to consider. In its 2015 Business School Data Guide, AACSB International reported that 22% of business school deans and 31% of associate deans are women. In accounting, 25% of full professors and 39% of associate professors are women. In finance, 11% of full professors and 25% of associate professors are women. The AACSB says that as faculty rank increases, the ratio of women to men decreases more for accounting and finance professors combined.

THE COMPENSATION GAP REMAINS CONSISTENT

In addition to the pipeline issues, there’s an ongoing conversation about the fact that women routinely earn less than their male counterparts in the same job. For the past several years, a commonly cited number is that women make about 78% of what men make for similar jobs, which often is referred to as the 22% wage gap. In its most recent report, with 2014 data, the U.S. Department of Labor in the Earnings section of its Women’s Bureau area indicates that women in financial and business operations occupations make about 75% compared to their male peers. In management occupations, the 22% gap is consistent.

The 2015 IMA Global Salary Survey , published in the March 2016 issue of Strategic Finance, indicates similar gaps, with a 71% gap in median base pay and 73% in total compensation. For women in the 50 and over age range, the gap improves at 82% and 85%, respectively. In 2015, Fortune reported that the 60 women CFOs in the S&P 500 earned more on average than their male counterparts, but, as mentioned earlier, having women in only 11%-12% of these roles is still very low (“Women Make More Than Men in This C-Level Position”).

IMA’s U.S. Salary Survey report indicated some other interesting results related to the difference between men and women:

….women rated overall job satisfaction as more important to their career satisfaction than did men (70% vs. 55%). How their employer handles ethical issues was rated far more important by men than women (59% of men vs. 24% of women). Men also rated their working relationships with others as more important than did women.

Women also rated being acknowledged and recognized for performing well on the job as more important than men did (53% vs. 35%). It’s possible that there’s a connection between this result and the previous discussions about differences in compensation and management level by gender. If women are getting paid less and feel underrepresented in the higher echelons of their company’s management, then they might feel that recognition of excellent job performance is more important to help them fight those imbalances. At the same time, not getting recognition under those circumstances likely contributes to a lack of job satisfaction. If so, then women might feel they need to fight twice as hard and get that much more recognition than their male equals in order to get the same advantages/advancement they do.

SYNTHESIZING THE DATA

Given the educational achievements of women in accounting and finance over the past few decades, is an increase of 30 women CFOs from 2000 to 2015 acceptable progress? Are the small percentages of women in the C-suite and on boards of directors really because of a small pool of candidates? Should we be concerned about the decline in women obtaining accounting and finance degrees? How can we move the meter on what seem to be steady and consistent compensation gaps? WALS participants said they are concerned about the progress and recognize the need to discuss, evaluate, and keep a watchful eye on the overall trends and even slight changes. They focused on ways to personally build leadership capacity to become more strategic and valuable to their employers.

MENTORSHIP AND SPONSORSHIP ARE POSITIVE ENABLERS

WALS participants also discussed the importance of mentorship and sponsorship and how both can be helpful for advancing their leadership skills. In terms of mentoring, the discussion largely included the benefits of having both male and female mentors. The group discussed how it’s common for aspiring women leaders to seek mentorship from women who are established leaders but emphasized how the importance of seeking male mentors who may offer different insight into leadership roadblocks women face was incredibly impactful. Many of the women who had already advanced to more-senior leadership roles stressed how the advice and guidance given by male mentors proved to be transformational to their career. For example, several described how they were recommended for promotions by male colleagues.

Other conversations centered around the concept of intergenerational mentoring, which involves having mentors from diverse generational groups such as Millennials, Gen Xers, and Baby Boomers. The approach can be effective because it creates opportunities to learn from and guide other professionals at various points in their career. Intergenerational mentoring can be useful for both men and women, and it can be particularly powerful for those who are ready for more responsibility than their current position allows. Intergenerational mentoring should be a two-way street, and, if it’s practiced in an intentional way, developing leaders can gain considerable insight into how to motivate, inspire, and advance individuals and groups. WALS participants agreed that being deliberate and focused in managing mentor relationships is a key for ensuring career impact. For example, establishing routine and regular ways to meet with their mentor was particularly important.

The group also talked about career sponsors, individuals who are in influential or more-senior positions who basically “go to bat for” the people they are sponsoring and help elevate their career opportunities or help them get promotions. Sponsorship is more structured than mentorship. Although sponsors can be difficult to find, women who have had a sponsor often discovered them by participating in formal networks or professional organizations. Some larger companies have formal sponsorship programs in place, which is great for those who work in that environment. The sponsor conversation at WALS emphasized how a best practice for finding sponsors is through participation in a professional organization such as IMA. This can be particularly helpful for women who work in small to midsize companies or for those who want to seek opportunities for advancement outside their current employer.

FOCUSING ON STRENGTHS

A particularly motivating part of the WALS workshop included discussion of personal strengths and how to use them to enhance the leadership journey. Participants shared what they believe are their top three to five personal strengths that have helped them achieve—for example, flexibility, adaptability, interpersonal skills, communication skills, and being great at multitasking and collaboration. In addition, strengths such as being a good listener, paying close attention to details, and being forward thinking helped them become successful accounting and finance professionals. The WALS presentation emphasized the importance of participants focusing on how to use their strengths to elevate their career path and avoid overemphasis on simply trying to overcome weaknesses. Playing to their strengths and articulating them to their coworkers, supervisors, support system, and those in their professional network can elevate their career potential and also enhance mentorship and sponsorship opportunities.

DEALING WITH BARRIERS

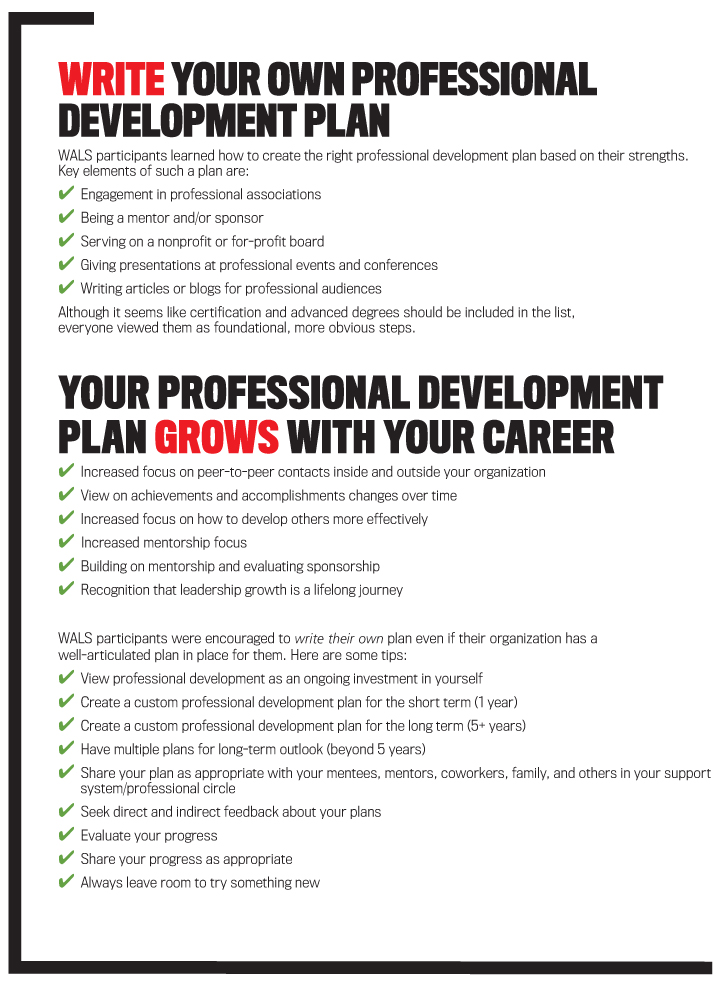

The topics of mentors, sponsors, strengths, and professional development plans brought up many positive suggestions and steps women can take to advance their leadership. But they also brought up examples of frequent barriers to leadership development for women.

Participants were most concerned about being evaluated on their ability to fit into the same molds as other leaders (male or female) in their organization. In terms of male leaders, the topic of women trying to fit in with the “guys” or adapting their leadership style so that they feel they are viewed as acceptable by male leaders was common. In addition, they were concerned about being stereotyped. The stereotype threat was often linked to worries about women being too emotional or not firm enough to serve in leadership roles often occupied by men. Other stereotype concerns were linked to being characterized as difficult or demanding when it’s necessary to be assertive or take a firm stand. Another important element was frustration about women not helping each other as much as they could or even creating roadblocks to participation or promotions.

CALL TO ACTION

Many WALS participants from small and midsize organizations had never been to an event that offered this kind of dialogue, and their call to action for more of these types of workshops was loud and clear. Participants from larger organizations expressed similar enthusiasm. Several asked, “How can we continue the conversation?” In addition, both men and women have asked me, “Why don’t you invite men to the event?” These are important questions, and the near-term answer is “We are just getting started, and a great deal of the conversation at the first four WALS workshops is setting the stage for further engagement.” But we do believe that having men involved with the series is incredibly important, so we’ll see what happens as this initiative evolves. In the meantime, we asked participants to offer some leadership advice to both men and women (see above).

The conversation definitely will continue. How will you contribute?

May 2016