Extending or deferring payment will result in conflicting liquidity measures. The larger payables balance will lower the current ratio, a result that’s interpreted as lower liquidity. On the other hand, the extended payment period will reduce the firm’s cash conversion cycle (CCC), therefore reflecting greater liquidity.

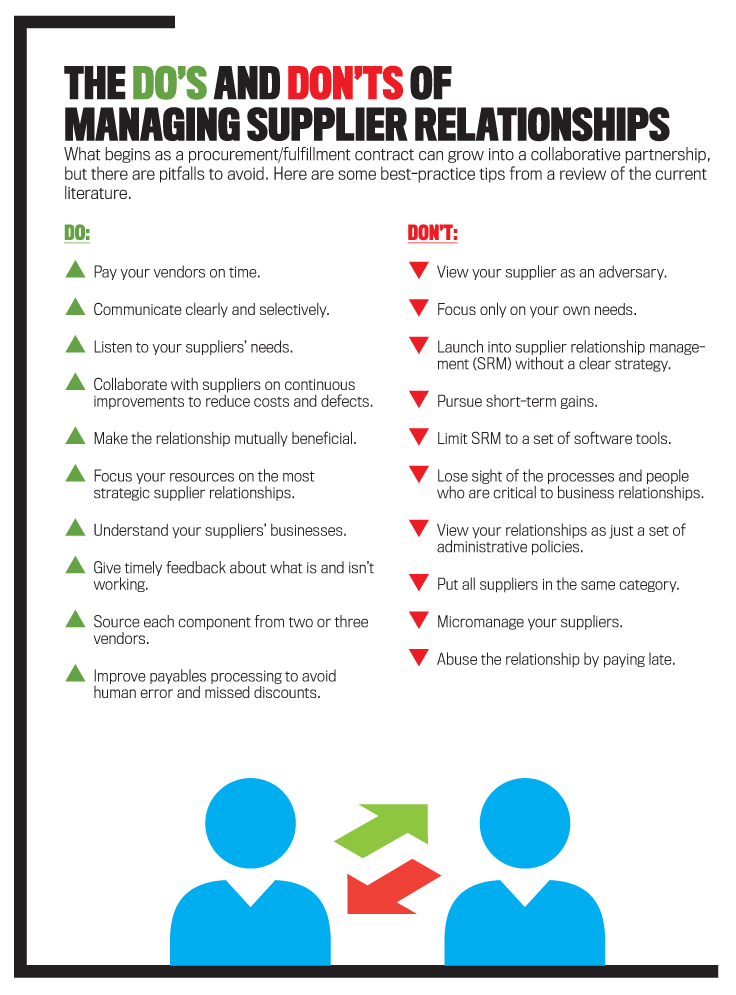

But there’s still more to the decision. Financial measures may not capture the full impact of a firm’s new policy toward vendors because the possible nonfinancial fallout isn’t considered. If the company ignored a prior agreement with the vendor to pay by a certain date, or if the company postponed payment for an unreasonable length of time, the results may include angry vendors and severe damage to vendor relationships.

FINANCIAL EFFECTS

Common measures of liquidity, such as the current ratio (current assets / current liabilities) and the quick ratio ((cash + marketable securities + accounts receivable) / current liabilities), provide a basic comparison of “near cash” assets to those liabilities that will require payment in the near term. Yet these static measures don’t necessarily provide insight about the time required to liquidate the current assets and actually pay the current liabilities. A company can address these concerns by incorporating the firm’s CCC into the liquidity analysis.

Briefly, the CCC is a combined measure of the number of days of financing required for inventory turnover and receivables turnover offset by the days of financing provided by the payables turnover. Using amounts provided in the financial statements, calculate the CCC as follows:

CCC = days’ inventory outstanding (DIO) + days’ receivables outstanding (DRO) — days’ payables outstanding (DPO)

where

DIO = average inventory / (cost of goods sold / 365)

DRO = average accounts receivable / (net sales / 365)

DPO = average accounts payable / (purchases / 365)

Note that for DPO, purchases are determined as cost of goods sold plus or minus the change in inventory. Another method is to use cost of goods sold rather than purchases when calculating the DPO. Cost of goods sold is a close proxy for purchases if inventory levels are relatively stable.

DIO and DRO, the first two components of the CCC, indicate how quickly the inventory and receivables are converted into cash that can be used to pay current liabilities. Knowledge of these time requirements can shed new light on whether you should interpret the static measure of the current ratio as favorable or unfavorable.

A low current ratio may be satisfactory if a quick turnover of inventory and receivables generates sufficient cash flow. For example, Walmart’s current ratio was only 0.88 in its 2014 annual report. In other words, the company’s current liabilities exceeded its current assets by 13.3%. Walmart acknowledged this working capital deficit as a part of its strategy for the efficient use of cash. The company is able to sustain this working capital position because it turns over its $45 billion inventory every 45 days and has minimal investment in receivables.

Alternatively, you may want to reevaluate a seemingly favorable current ratio if there’s a significant buildup of inventory and/or receivables. The current ratio may be less favorable (or even unfavorable) if the time required to liquidate the current assets is unsatisfactory. As an example, Circuit City’s current ratio was 1.52 less than nine months before the company filed for bankruptcy. But based on the company’s 2008 annual report, its DIO was 63 days. Leading competitor Best Buy had a current ratio at that time of only 1.08 but a DIO of 52 days. Circuit City’s combined DIO and DRO was 17 days longer than Best Buy’s, reflecting less-liquid assets in Circuit City’s current ratio (see Figure 1 for a comparison of the two companies).

DPO, the third component of the cash conversion cycle, reduces the overall CCC by the number of days the organization is able to preserve its cash on hand by deferring payments to vendors. In times of financial distress, a lengthy DPO may be necessary as management prioritizes cash payments in an effort to preserve cash flow without disrupting operations. Even when financial distress isn’t an issue, however, management may view vendor payables as a source of interest-free financing. Authors Corey S. Cagle, Sharon N. Campbell, and Keith T. Jones in a May 2013 Journal of Accountancy article, “Analyzing Liquidity Using the Cash Conversion Cycle,” noted that “the longer a company is able to delay payment (without harming vendor relations), the better the company’s working capital position.” Therefore, the buildup of payables may reflect a company’s strategic management of its CCC even though the static measure of the current ratio is penalized.

Yet enhancing liquidity by extending vendor payments can be a costly decision when a vendor offers discounts for early payment. A study by Chee K. Ng, Janet Kiholm Smith, and Richard L. Smith in the June 1999 Journal of Finance, “Evidence on the Determinants of Credit Terms Used in Interfirm Trade,” indicates that discounts tend to be offered by larger vendors within certain industries. Therefore, they aren’t as common as textbooks would lead you to believe. When vendors offer them, the discount terms can vary significantly, but the most common terms are 2/10, net 30 (that is, a 2% discount if paid within 10 days, otherwise payment is due in 30 days). Theoretically, the annualized cost of a 2% savings for a 20-day earlier payment is in excess of 40%. (Of course, the annualized cost of not taking the discount is reduced when payment is deferred beyond the 30-day due date.)

Even when the vendor doesn’t explicitly offer discounts, extended payment terms may have a cost. The vendor may be bundling the cost of financing with the cost of the product, which presents an opportunity to negotiate a lower price for early payment. The point is that, when setting policy regarding vendor payments, even when focusing solely on the financial aspects, there are nuances that financial managers should consider.

NONFINANCIAL EFFECTS

A company’s CCC can provide valuable insight about its existing liquidity position, but any discussion of managing vendor payments is incomplete without considering the potential nonfinancial effects of the DPO decision. The manner in which a company manages its liquidity can impact both its internal and external relationships. As noted above, the benefits of extending vendor payments seem to be commonly accepted as long as this can be accomplished without harming vendor relations. Cagle, Campbell, and Jones say, “A shorter CCC is favorable, and it’s entirely possible to have a negative CCC” resulting from extending vendor payments beyond the combined time required to sell the inventory and collect the receivable.

They cite Dell Inc. as one of the leading examples of efficient CCC management. According to Dell’s annual report ended February 1, 2013, the last year available before the company went private, the company’s CCC measures for fiscal years ended 2011 through 2013 were -33, –36, and -36 days, respectively. These negative CCC measures reflect a growth in Dell’s DPO from 82 days in 2011 to 93 days in 2013. From a financial perspective, this would seem to be an extremely effective approach to working capital management. In fact, Dell refers to that growth in its DPO as an improvement.

Other large companies also delay payments to receive increased financial benefits. For example, Amazon, Procter & Gamble, Kimberly-Clark, and others have experienced significant growth in DPO in recent years, according to a September 30, 2015, story by Justin Fox for BloombergView. Such aggressive forms of vendor management are typically available only to firms with the financial muscle to force compliance.

From a supply chain perspective, the ripple effects are hard to ignore. Extended vendor payments can create uncertainty and distress throughout the distribution channel because of the financial burden placed on upstream suppliers, especially smaller suppliers. Just like their larger customers, smaller vendors prefer to collect sooner rather than later. The situation is analogous to that of the construction industry, where contractors rely on the collection of progress billings to provide the working capital they need to pay for materials and labor to complete the contracted work. In similar fashion, vendors incur many up-front costs for material, labor, and overhead when fulfilling an order. These vendors rely on collections to provide the working capital needed by operations that are filling the distribution channel to meet customer demand. Attempts by customers to extend vendor payments without harming vendor relations may ultimately backfire because efforts to absorb the ripple effects result in higher costs that the company must cover by raising prices. In the extreme, the ripple effects may actually result in a tsunami that leads to vendor failure and the need to find a replacement source of supply.

In addition to the external distress created throughout the supply chain, an aggressive stance toward vendor payments can also create distress within the slow-paying company itself. All corporate relations ultimately rely on humans, and human employees are the ones who administer corporate policies. Employees who deal directly with vendors must sometimes deal with emotion-filled responses to their employer’s slow-paying behavior. As a result, not only are vendor relationships strained, but the work environment can become negative, stressful, and produce organizational/professional conflict.

Anecdotal evidence provides additional support for the idea that aggressive corporate policies can result in personal fallout for employees. One of the authors of this article, when beginning work at a Fortune 100 company, was told that it was routine corporate practice to halt payments to virtually all vendors toward the end of the company’s fiscal quarter. It wasn’t because of a lack of cash, but rather the company wanted to maximize DPO and thereby lower its CCC. New employees in the department were given some basic training on how to handle urgent calls from vendors, although securing a timely payment to a vendor (according to the agreed payment terms) wasn’t in the toolkit. Entering such an environment was indeed stressful.

Returning to the example of Dell, according to an April 1, 2013, Forbes article by Stephen Satterwhite, “Dell’s Poisonous Culture Is Sinking Its Ship—and Raises Questions for Potential Buyers,” Dell had a “poisonous culture” that affected Satterwhite’s own company, a Dell supplier. Ultimately the conflict led to the end of the business relationship as well as the loss of some of his better employees. Although Satterwhite doesn’t explicitly address Dell’s strategy toward vendor payments, his experience as a vendor to Dell is insightful. Those who develop corporate policies must consider the effects of those policies on the people who must administer them.

AN ETHICAL CONFLICT?

Professional values, as described in codes of professional conduct from organizations such as IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) are typically grounded in the concept of integrity. For example, the principles of the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice include honesty, fairness, and the responsibility of members to act with integrity. And according to Article 3 Section 0.04 of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Code of Professional Conduct, “Integrity is measured in terms of what is right and just.” When corporate policy dictates that vendor payments be deferred as long as possible, individuals who work within the accounting and finance function may find their professional values in conflict with organizational outcomes. In other words, the distress put on vendors as the result of slow payments may lead employees to question whether the policy toward vendors is right, just, and fair. An aggressive policy toward vendors may be self-defeating if the policy leads to internal job dissatisfaction and increased turnover.

Managing vendor payments is an important activity that can have a direct impact on liquidity and corporate relations, yet vendor-management policies can also have a more subtle and negative impact on employee satisfaction and turnover. Perhaps the CCC isn’t the only benchmark of importance. In the matter of managing vendor payments, a financial manager must also ask what is fair, honest, and reflects integrity.

May 2016