No, we aren’t going to enter into some heavy philosophical musings here. Instead, we’re most interested in structuring a learning environment where individuals—including management accountants and other financial professionals—can develop an ethical foundation for making good decisions and judgments in the business world. In her article for Phi Delta Kappan magazine, “Not Teaching Ethics,” Alexis Wiggins proposes that traditional teaching methods don’t work very well. She has experimented with various methods and concludes: “I realized that the best way to teach ethics may not be about the content of ethics at all but the process by which students learn.” Based on her experimentation, she changed her teaching method from a didactic one to guiding deeper learning through conversation and discovery. She now considers herself a coach and concentrates on bringing out the best in people.

For most of us, however, coaching isn’t easy. Unlike teaching, which concentrates on developing content and different ways to present it, coaching has the added complexity of needing to respond to changing circumstances. From teaching, coaching, and working with undergraduates and businesses, we’ve learned the following six practical principles for structuring learning so that both business major undergraduates and employees can experience ethical concepts, principles, and behaviors.

-

Using examples is better than lectures for teaching business ethics.

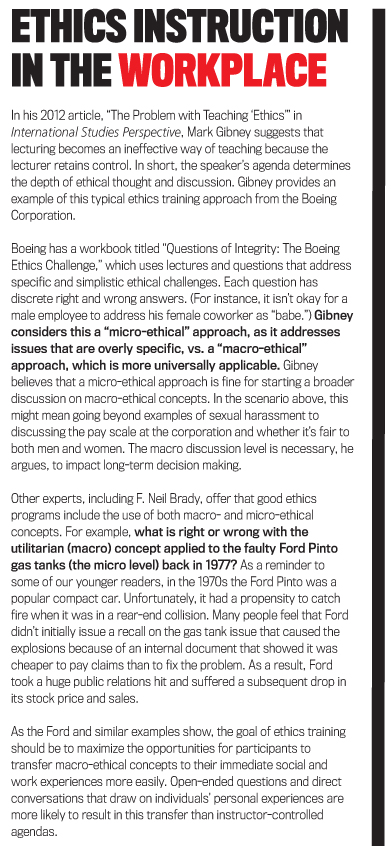

We use very few true lectures when we teach ethics. The longest is about 40 minutes and covers absolutism and relativism. While these notions are important, they aren’t that helpful for business school undergraduates learning to think about ethical dilemmas.

Don’t get us wrong—lectures are a great way to cover large amounts of information. But we’ve found that students generally retain little of what they’ve heard. In addition, many of our students can recite definitions but struggle with translating those definitions into a real-life situation. This indicates that lectures do little to change thinking or behavior regarding right and wrong decisions. More importantly, lectures don’t provide the context necessary to allow students to assimilate ethics into their decision-making process.

In the business environment, lectures correlate with the propensity of many human resource and training staff to become a “talking head” at the front of the room. It’s faster and easier to simply read the code of ethics to staff members every year. There’s a similar lack of retention in this environment, too. Employees willingly sign off that they’ve been informed and yet a day later can rarely remember more than one or two points from the lecture. When asked about the relevance of the code of ethics, most employees fail to see any practical application.

In short, we believe lectures should be used to provide the philosophical foundation for ethics in business decisions. Then, specific examples should be introduced to broaden the conversation and lead it to a macro-level discussion.

-

Sharing a personal ethical dilemma helps open the mind.

Personal ethical dilemmas engage the minds of both students and seasoned employees. The basis of many personal dilemmas is the heartfelt unrest that employees experience during awkward situations they encounter while working. “Did I do the right thing?” is the critical question to ponder in a class or a workshop designed to improve ethical business decision making.

To introduce personal reflection into the classroom experience, we require our students to write a paper that addresses a situation in which they had difficulty telling right from wrong. To further encourage introspection, we professors also share our own personal ethical dilemmas. Our favorite story is about paying to be included in a book anthology, which each of us did independently by contributing chapters to different books, in order to become published authors. At the time, this seemed to be a sound business decision. In retrospect, we both questioned whether we compromised our values in order to gain more business credibility.

It can be more challenging to incorporate personal reflection in the business environment. An effective method that we use is to introduce short ethical scenarios—tailored to specific industries, including management accounting—that could have occurred in the employee’s workplace. Using a series of leading questions, employees discuss the scenario and its implications in small groups of three to five. Our experience has shown that people are generally more comfortable, and therefore more open to personal reflection, when group size is limited. To deepen the learning experience, we then facilitate a discussion among all participants, highlighting the similarities and differences in viewpoints and experiences.

What’s the benefit of this approach? Personal challenges often create an atmosphere of doubt where people frequently address the question, “Was I wrong?” or its corollary, “Was I right?” This learning moment opens up many opportunities to integrate comprehension and encourages personal introspection. By facilitating a discussion and adding key ethical viewpoints and theories that back up or contradict students’ and employees’ comments, the instructor provides an environment that guides individuals to incorporate ethical viewpoints into their thinking process.

Feedback that we’ve received from participants has indicated that the discussions of personal ethical dilemmas were an effective teaching method. The introspection and plain talk that often challenged the ethical status quo made these learning moments quite effective.

-

An exploration of personal values adds depth and meaning.

Even when students or young employees are engaged, it’s difficult to have a rich exploration of business ethics with individuals who don’t yet have a firm grasp on what they believe in. But it isn’t just young people who are going through this process: Since exploring personal values has only recently been added to the business curriculum, and only at select universities, many older workers also have a limited comfort level and experience with discussing their personal values.

In the ethics classes we teach, we devote several training periods to discussing how personal values regarding duty, family, integrity, wealth, justice, fairness, and power, among others, may conflict with each other. We have our students define these terms early in the semester, then review the words regularly and see how the meanings evolve as the class progresses.

In the business environment, management is responsible for creating an ongoing conversation about both personal and corporate values. Training sessions may be brief at 30 to 45 minutes each. Best practices require these conversations to be held in small groups at least once a month. In many companies, the task may be delegated to department leaders, who should be properly trained in the facilitative approach. Ethical leadership and development of others go hand in hand. In short, supervisors and department managers, as well as the company, will benefit when discussions are open and interactive.

In the classroom, the concept of civic duty has generated the most energized debates. Early in the semester, most students want to talk about paying taxes, voting, and jury duty. Discussions intensify, and responses become more varied as we dig deeper into personal values and ethical theories. At this point, as instructors, we begin to challenge the surface and facile answers by asking how many students avoid jury duty. By directing the conversation to how jury duty avoidance is a personal behavior related to individual values, we’re able to elevate the discussion to a macro level that still touches each student on an individual and personal level.

We’re further able to elevate the discussion by introducing the ethical concept of fairness into the conversation. Are students who actively avoid jury duty being “fair”? More broadly, does failing to serve as jurors jeopardize the fairness of the system?

In the business environment, the jury duty example is highly relevant in that the topic can be supplemented with how civic duty impacts the workplace on an individual basis, as a department, and as a company. How do personal values, which differ among employees, impact others? Are employees who avoid or embrace their civic duties being fair? Does it enhance or detract from the company’s mission and values? Where’s the “greater good”?

The discussion of personal values has a twofold benefit. First, it engages the student, who can personally relate to the content and assimilate it more easily. Second, it enables the instructor to cover ethical topics on both a macro and micro level at the same time.

-

Smaller, less egregious felonies are better than bigger, more egregious ones for exploring the more subtle aspects of ethical thought.

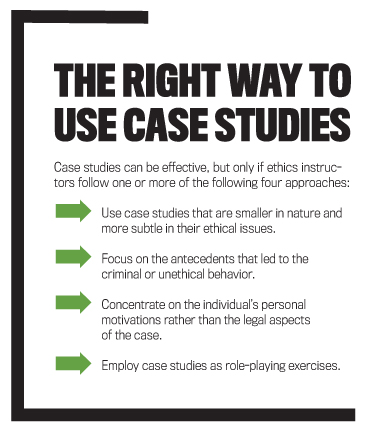

When given ample class time to discuss personal dilemmas and values, students are prepared to apply what they’ve learned to business ethics. Case studies are helpful but can be misused. For example, our students read about Enron, Tyco, WorldCom, Bernie Madoff, British Petroleum, and Peanut Corporation of America. The majority of students refer to the participants in these well-known business scenarios as “greedy” and “criminals.” Even with questions that steered the conversations toward relativism (Did British Petroleum follow basic engineering protocols?), the undergraduates were adamant that the perpetrators’ fraud or negligence was based on greed. Moreover, students say they believe that all the participants were criminals and should be in jail. The egregious misconduct in most of these headline cases skewed the ethical conversation toward the criminal aspects.

Seasoned financial professionals may review case studies on their own or hear them discussed at association meetings. For example, IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) has invited people like Cynthia Cooper from WorldCom and Eddie Antar of Crazy Eddie, the now-defunct chain of electronics stores, to speak at its Annual Conference & Expo. Conversations after these presentations indicate that attendees have reactions similar to those of our students.

Smaller, less egregious case studies offer more opportunities for individuals to see that all unethical behavior isn’t black and white. They find it easier to dig below the infraction and discuss the ethical values that impact decision making. The more important lesson in most case studies is that a series of smaller decisions may lead to ethical misconduct, which may or may not lead to jail.

By concentrating on the events that led up to the criminal or unethical behavior, students and professionals become sensitized to the more nuanced aspects of ethical decision making. Our job as ethics educators is to help them identify the defining moment in these scenarios. Focusing on when and where the fraud began exposes participants to the difficult pressures and decisions that occur in business. We found, for example, that “doing nothing” presented quite an ethical dilemma for undergraduates to ponder. On the other hand, seasoned business people are amazed at how easy it is to inadvertently procrastinate or ignore the situation, hoping it will go away. Further discussion questions include, “At what point is it too late to turn back?” and “Is it ever too late?”

Our conversations with students go beyond the legal aspects to concentrate on discovering what motivations beyond greed might be involved. Student-generated discussions focus on issues of belonging, making a name, respect, and being a good employee. We broaden these debates to a more macro, or universal, level by relating them back to what the students had disclosed earlier about their personal values.

In any ethics scenario, another worthwhile approach is to research and debate the behavior of the workers, supervisors, and lower-level managers: specifically, why they didn’t know about or didn’t take action against the criminal behaviors. We encourage participants to role play and “become” these people to better understand their motivations and dilemmas. Once participants do this, they start to understand the pressures that the employee experienced and begin to see more shades of gray. The role playing also contributes to learning right from wrong when the students acknowledge personal responsibility in the face of “my boss told me to do it.”

Case studies are a valuable teaching tool. Yet those that are less well known and involve lower levels of management provide greater learning opportunities. They can be further leveraged by investigating antecedents (events that preceded other events), discussing motivations, and role playing.

-

Controversy is good for thought.

One of the highlights of our ethics courses is the controversial class discussions regarding working for a tobacco company. In class, we view whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand on YouTube testifying about the lies and deceit waged by “big tobacco” on the public. Everyone in the classroom acknowledges that smoking is hazardous to your health.

But here’s where things get interesting: If an undergraduate business major could get 10% more salary a year with Philip Morris, the majority said, “That’s a no-brainer. Of course I would go with the job that paid more money.”

To encourage controversial and opposing opinions, we ask, “Is it ethical to sell cigarettes to children?” Initially, the reaction is straightforward: The buyer of the cigarettes is responsible for his own welfare. The relative nature of promoting smoking to children, however, leads to a deeper discussion about whether kids are capable of making an informed decision.

Although this controversial class discussion initially skews toward talking about money, it transitions to involving students in the nuances of many real-life decisions. By the end of our class, students are no longer as adamant that working for a tobacco company—or even an advertising company that promotes smoking—is ethical.

The class discussions regarding working for a tobacco company eventually became a highlight of our courses and seemed to mark a turning point in the depth and intensity of student engagement.

While businesses can teach ethics using this same scenario, most employees find more impact in evaluating controversies that are currently happening in their industry or in the news. For example, recent articles on the FIFA corruption scandal, in which current and former officials of the world soccer governing body were accused of accepting bribes, may be distributed, read, and summarized. While many employees will be ready to condemn FIFA and its officials, a more-nuanced discussion can be fostered by asking questions such as, “Is it ethical for Visa to withdraw its sponsorship of FIFA?” and “Should they be required to wait until guilt is proven? Why or why not?”

The conversation may be deepened further by delving into whether the FIFA president should have been aware of the ongoing issues and possibly done something to prevent the current scandal. Finally, discussion could be steered toward how the actions of one person or a small group of individuals have the ability to impact the reputation of the entire organization.

-

In-person instruction is more impactful than online courses.

More and more colleges are offering online business ethics courses as a convenience to students who are also working full- or part-time. Likewise, in the business arena, a large proportion of corporate ethics training consists of an annual online ethics course followed by multiple-choice questions. It’s an efficient and economical format since it provides maximum flexibility for staff and easy tracking for management.

Even though we can see the appeal of online ethics courses, we feel strongly that they shortchange students, employees, and organizations. Why? Since two-way discussion is critical to effectively integrating ethical knowledge (as reflected in individuals’ thinking and behavior), in-person facilitation is preferable for ethics courses. In the business environment, ethics conversations serve the additional benefit of highlighting those individuals whose values may differ from those of the organization and may not be a good fit going forward.

Here’s a good example: When we asked a small group of management accountants what they considered “stealing,” one insisted that even a penny taken improperly constitutes theft. Another person, however, after pressing us to specify an amount, said he wasn’t troubled by anything under $20; a theft of that small magnitude was “irrelevant.” It was later discovered that this same employee was writing off open invoices rather than making collection calls. In his mind, the small amounts he stole weren’t relevant, but when totaled they represented a significant loss of income.

This is the kind of good information that can come from personal interactions. When courses are offered in an online or electronic format, extensive thought should be given regarding how to emulate the extemporaneous conversations that occur during facilitated, in-person discussions. Too many instructors take this aspect of ethics education lightly. They shouldn’t.

NO EASY ANSWERS

Ethics isn’t a subject well served by the didactic transfer of information. Traditional, pedagogical methodology leads to comprehension but little change in behavior. Therefore, best practices in ethics instruction will involve participants in the sometimes difficult process of critical thinking and clarifying or challenging their personal values.

Our experiences have taught us that actively engaging people in learning business ethics is the best way to impart real and lasting knowledge and understanding. While lecture time can provide the theoretical information that will enrich later conversations, it should be kept to a minimum and imparted in small chunks. Discussions of personal dilemmas and values open students’ minds to broader interpretations of right and wrong.

Finally, in-class discussions that challenge and stretch individuals’ thinking are key to creating a lasting impact on future business ethical decision making for young students and older, more-established employees alike.

May 2016