The United States is one of two countries that have a citizenship-based tax system for both individual taxpayers and entities. This means that any “U.S. person” (in other words, any individual who isn’t considered a nonresident alien for tax purposes) is subject to U.S. tax laws, regardless of where he or she lives and earns income. In addition, U.S. taxpayers who are involved in activities outside the U.S. increasingly face complex reporting and disclosure requirements.

Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §7701 defines the term “U.S. person” for individuals and entities. In the case of an individual, a U.S. person includes U.S. citizens, permanent residents, and those who meet the “substantial presence test.” The basic rule for the test is that individuals have to have been in the United States for at least 31 days in the current tax year and a total of 183 days or more (counting 100% of the days in the current tax year, one-third of the days in the year before that, and one-sixth of the days in the tax year two years ago). Included in those numbers are the days of arrival and departure. Not included are the days where the taxpayer was considered an exempt individual (due to a medical condition; being a student, teacher, or trainee; or holding an F, J, M, or Q visa).

FOREIGN REPORTING RULES

Individual taxpayers subject to foreign reporting rules fall into two major categories: (1) those who live abroad and therefore are most likely earning income abroad and (2) those who live in the U.S. but have foreign earnings, including noncitizen nonresidents who spend enough time in the U.S. to be treated like a U.S. citizen for income tax purposes.

A U.S. taxpayer involved in some international activities may be subject to certain disclosure requirements, namely, the Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR) and the Financial Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA). If the taxpayer has control over a foreign entity—either incorporated or unincorporated—additional reporting requirements apply: Form 5471 for officers, directors, or shareholders in certain foreign corporations and Form 8865 for certain partners of foreign partnerships (IRC §6038 and §6046).

FBAR AND FATCA REPORTING

According to the FBAR requirements, anybody who has a financial interest or signature authority over a foreign financial account—such as a checking, savings, or brokerage account—exceeding $10,000 in aggregate on any day during the calendar year—must report the account information (name of the bank or financial institution, account number or other designation, and address) as well as the maximum amounts for each account (translated into U.S. dollars). This information must be reported electronically using Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) Report 114 by June 30 of the following year. No extension is available.

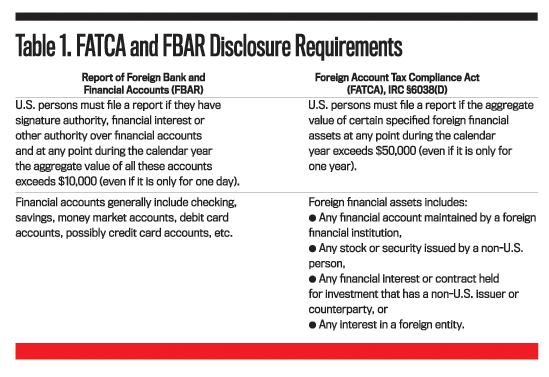

According to lawmakers and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), FATCA is a means to increase compliance by U.S. taxpayers with foreign accounts. It focuses on U.S. taxpayers and their disclosure of their foreign financial accounts and offshore assets as well as on the foreign financial institutions and their reporting of financial accounts held by U.S. taxpayers and foreign entities with substantial U.S. taxpayer ownership interest. New disclosure requirements were put in place in addition to the existing FBAR. Table 1 summarizes the two disclosure rules for individual taxpayers.

U.S. taxpayers who meet the FATCA filing requirements must use Form 8938 to report financial information for all foreign deposit and custodial accounts and certain other foreign assets, including address and ownership, account balance (or maximum value) and interest, dividends, royalties, and other income earned. If the foreign account or asset has been reported on another required form—such as Form 5471—it doesn’t need to be disclosed on Form 8938, but the respective form must be referenced in Part IV of Form 8938, which must be attached to the individual income tax return (Form 1040 or 1040NR) and filed by the due date (including extensions) for that return. Filing Form 8938 doesn’t relieve the taxpayer from a potential FinCEN 114 disclosure requirement.

Penalties for failing to file the disclosures are quite steep. In the case of FinCEN 114, they start at $10,000 and increase by $10,000 for each 30-day period after being notified by the U.S. Treasury. The maximum penalty is $50,000 (plus interest). If taxpayers can demonstrate reasonable cause, the penalty may be waived. Depending on the situation, different approaches must be taken when filing a late FBAR. In many cases, no penalties will apply if the late filing is not willful and the taxpayer provides a reasonable explanation for filing late. Similar rules and penalties apply to taxpayers who neglected to comply with FATCA requirements, with a $10,000 penalty per account (up to six years of nonfiling) if the IRS finds that the failure wasn’t willful, or, if willfully not filed, a penalty of 50% of the account balance (capped at $100,000).

FORMS 5471 AND 8865

Another disclosure requirement applies to officers, directors, and owners of certain foreign entities. Specifically, U.S. officers, directors, or owners of a foreign corporation in which a U.S. person has acquired more than 10% of the stock must file Form 5471. U.S. persons who controlled a foreign partnership (category 1 filer), constructively owned more than 10% of the partnership (category 2 filer), contributed property in exchange for foreign partnership interest if either the interest exceeds 10% or the property exceeds $100,000 (category 3 filer), or had a reportable transaction with a foreign partnership (category 4 filer) must file Form 8865. In certain cases when multiple persons have the same filing requirements, a joint information return that contains the required information may be filed.

As with the FBAR and FATCA, reporting these forms doesn’t result in additional taxes. But the foreign corporation’s or foreign partnership’s balance sheet and income information, as well as any transactions between the foreign entity and the U.S. taxpayer, must be disclosed. The initial penalty for failing to file either Form 5471 or 8865 is $10,000 per form. Depending on the filing category and the specific situation, additional charges apply unless the taxpayer can demonstrate that the noncompliance wasn’t willful and didn’t affect the tax liability.

BE AWARE

Many taxpayers are subject to foreign income reporting rules—even if they aren’t living abroad or aren’t aware of being connected to foreign assets or income earned outside the U.S. Taxpayers and preparers need to be aware of the various reporting and disclosure rules and deadlines because the penalties can substantially add to anyone’s tax liability. Several groups of taxpayers are especially affected by these laws, namely individuals who are subject to U.S. tax rules because they meet the substantial presence test, individuals who don’t know that they have signature authority over foreign accounts, and U.S. taxpayers who are living abroad.

© 2016 A.P. Curatola

March 2016