The SEC has taken a dramatic series of first-time actions cracking down on violations. In June 2014, the SEC announced its first anti-retaliation enforcement action, followed in August 2014 by its first whistleblower award to a compliance or internal audit employee. In March 2015, the SEC made its first whistleblower award to a company officer, followed a month later with its first enforcement action against restrictive language in confidentiality agreements. That same month the SEC made a whistleblower award of more than $1 million to an internal compliance officer.

SEC Chair Mary Jo White reinforced the tone of increased vigilance in an April 2015 speech to the Garrett Institute, warning that companies should take a hard look at whether their boards and senior management are championing key whistleblower issues. She concluded, “Gone are the days when corporate wrongdoing can be pushed into the dark corners of an organization.”

The SEC’s “2015 Annual Report to Congress on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program” further underscored the new get-tough attitude. Sean McKessy, SEC Chief of the Office of the Whistleblower, reported that the nearly 4,000 SEC whistleblower tips received in fiscal year 2015 reflected a greater than 30% increase from about 3,000 tips received in fiscal year 2012. McKessy also stated that “the Commission has paid more than $54 million to 22 whistleblowers since the Commission’s new whistleblower rules went into effect in August 2011.”

All these events clearly show increased scrutiny of CFOs charged with corporate governance, who now must heighten the level of diligence about whistleblower programs.

WHO IS A WHISTLEBLOWER?

In 2010, Congress created the SEC Whistleblower Program through Section 922 of the Dodd-Frank Act to provide a monetary incentive for whistleblowers to report violations of the federal securities laws. But who qualifies as a whistleblower?

According to the SEC’s Final Rules for implementing the program, an eligible whistleblower is an individual who voluntarily submits original information to the SEC (either by completing an online questionnaire or SEC Form TCR) that leads to a monetary sanction greater than $1 million in a Commission enforcement action. An eligible whistleblower doesn’t need to be an employee of the company. And employees with compliance or internal audit responsibilities aren’t normally eligible whistleblowers—unless the whistleblower first communicated the matter internally to appropriate officers or board members who then failed to take corrective action after a period of 120 days.

Whistleblowers may be eligible for an award of 10% to 30% of SEC monetary sanctions collected. To receive the award, they must submit an application (SEC Form WB-APP) within 90 calendar days of the date of an SEC Notice of Covered Action, which is published on the SEC website to indicate the imposition of monetary sanctions totaling more than $1 million.

The amount of the whistleblower award is determined by several factors, according to Section 240.21F-6 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. A bigger award may be warranted when whistleblowers provide (1) significant information related to a successful enforcement action, (2) a high level of assistance to the SEC during the investigation, (3) particular support of the Commission’s law enforcement interests, and/or (4) evidence that they participated in the company’s internal compliance systems. But an award may decrease to the extent that whistleblowers (1) have been culpable or involved in the securities violations in some way, (2) unreasonably delayed in reporting the matter to the SEC, and/or (3) interfered with established company internal compliance and reporting systems.

Note that the SEC rewards whistleblowers who participate with a company’s internal compliance programs and penalize those who interfere with such programs. But might the SEC Whistleblower Program undermine the internally established compliance and reporting functions within public companies? SEC Chair White responded to those concerns in her April 30, 2015, speech delivered at Northwestern Law School to the Garrett Institute. White said, “The final whistleblower rules established a framework to incentivize employees to report internally first.” Moreover, the SEC’s “2015 Annual Report to Congress on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program” states:

The whistleblower program was designed to complement, rather than replace, existing corporate compliance programs. While it provides incentives for insiders and others with information about unlawful conduct to come forward, it also encourages them to work within their company’s own compliance structure, if appropriate.

RECENT WHISTLEBLOWER ACTIONS

Let’s take a closer look at these new or first-time SEC whistleblower enforcement actions against public companies. There were several types of actions involving (1) the company compliance or internal audit employee as the whistleblower, (2) a company officer as the whistleblower, (3) confidentiality agreements with language that restricts employees from reporting violations to the SEC, and (4) retaliatory actions taken against a head trader employee who informed the SEC about his company’s improper disclosure. SEC whistleblower cases can result in monetary sanctions exceeding $1 million being imposed on the public company.

$1 Million-Plus Award to a Compliance Officer

In April 2015, the SEC reported an award of more than $1 million to a compliance officer. According to SEC Final Rule Section 21F-4, an employee whose principle duties involve compliance or internal audit responsibilities isn’t normally eligible for a whistleblower award unless at least 120 days have elapsed since the information was reported internally. But in this case, SEC Director of Enforcement Andrew Ceresney stated, “This compliance officer reported misconduct after responsible management at the entity became aware of potentially impending harm to investors and failed to take steps to prevent it.” This was the second award for a whistleblower employee with audit or compliance responsibilities (the first occurred in 2014).

First Whistleblower Award to a Company Officer

In March 2015, the SEC announced its first whistleblower award to a former public company officer who voluntarily provided original, high-quality information about a securities fraud that led to more than $1 million in SEC enforcement sanctions. The announcement stated that “officers, directors, trustees, or partners who learn about a fraud through another employee reporting the misconduct generally aren’t eligible for an award under the SEC’s whistleblower program.” But an exception applied in this case because the officer reported the information to the SEC more than 120 days after the information was reported internally and the company didn’t take corrective action. Ceresney commented that “corporate officers have front-row seats overseeing the activities of their companies, and this particular officer should be commended for stepping up to report a securities law violation when it became apparent that the company’s internal compliance system was not functioning well enough to address it.”

First Whistleblower Case Against Restrictive Language

In April 2015, the SEC announced action against public company KBR, Inc. for violating whistleblower protection Rule 21F-17 by using confidentiality agreements that could stifle a whistleblower from communicating possible securities violations to the Commission. In her April 2015 speech to the Garrett Institute, SEC Chair White indicated that “Rule 21F-17 clearly states that no action may be taken to impede an individual from communicating directly with the Commission staff about possible securities laws violations, including by enforcing or threatening to enforce confidentiality agreements that could be read to limit such communications.” And when the SEC announced the first whistleblower case involving restrictive language, Ceresney said, “We will vigorously enforce this provision [Rule 21F-17].” But in response to public concerns about the enforceability of all confidentiality agreements, White used her Garrett Institute speech to assure that confidentiality agreements that address attorney-client privilege or protect company trade secrets and other confidential information aren’t prohibited.

First Anti-Retaliation Action

June 2014 marked the first time the SEC took action in response to retaliatory behavior toward a whistleblower who was the head trader of a hedge-fund advisory firm. The whistleblower reported trading activity to the SEC that showed his company was engaged in prohibited principal transactions. In her 2015 speech to the Garrett Institute, White said, “After the trader notified the company of the report to the Commission, the company immediately began retaliating, including by removing the whistleblower from the head trader position, stripping the whistleblower of supervisory responsibilities, and, ironically, changing the whistleblower’s job function from head trader to a full-time compliance assistant.” In announcing the action, Director of Enforcement Ceresney emphasized that the SEC was sending a strong message to public companies that might want to retaliate against whistleblowers. “Those who might consider punishing whistleblowers should realize that such retaliation, in any form, is unacceptable,” he asserted.

SEC’S 2015 WHISTLEBLOWER REPORT

So how can we sum up the SEC Whistleblower Program so far?

In the SEC’s “2015 Report to Congress on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program,” Office of the Whistleblower Chief Sean McKessy identified three important components of the program: (1) monetary awards, (2) retaliation protection, and (3) confidentiality protection. McKessy further indicated that of the $54 million in total award payments to 22 whistleblowers since the Commission’s new whistleblower rules went into effect in August 2011, “in fiscal year 2015 alone, more than $37 million was paid to reward whistleblowers for their provision of original information that led to a successful Commission enforcement action with monetary sanctions totaling over $1 million.”

Since the awards have exceeded $54 million and since eligible whistleblowers receive awards of 10% to 30% of related monetary enforcement sanctions collected, we can estimate that the total of such monetary enforcement sanctions collected so far under the SEC Whistleblower Program range from about $180 million to $540 million. In addition to these monetary benefits, the SEC Whistleblower Program is also supported by the noble purpose of promoting compliance with federal securities laws and protecting investors from the financial harm caused by federal securities laws violators.

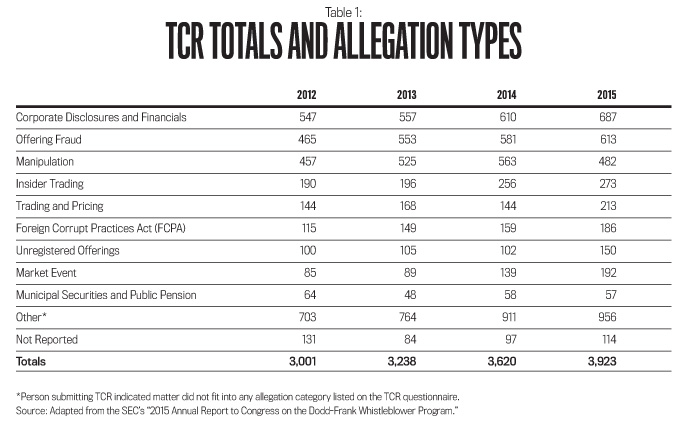

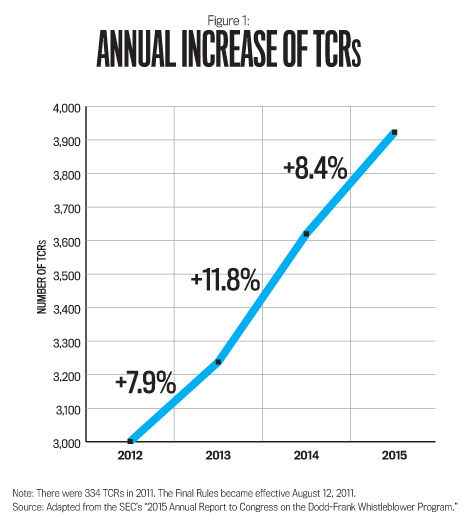

Table 1 provides the total number of Whistleblower Tips, Complaints, and Referrals (TCRs) received by the SEC during the first four full fiscal years (2012-2015) since the Whistleblower Final Rules became effective on August 12, 2011. As Figure 1 shows, total annual TCRs increased by almost 31% during the three years ending in fiscal year 2015.

Corporate disclosures and financials, offering fraud, and manipulation represent the top three whistleblower complaint categories for each year presented. In fiscal year 2015, whistleblower submissions were received from individuals in all 50 states and in 60 foreign countries, with persons in foreign countries submitting 421 TCRs. The most foreign country submissions received were from the United Kingdom (72), Canada (49), and China (43).

TOP WHISTLEBLOWER PAYOUTS

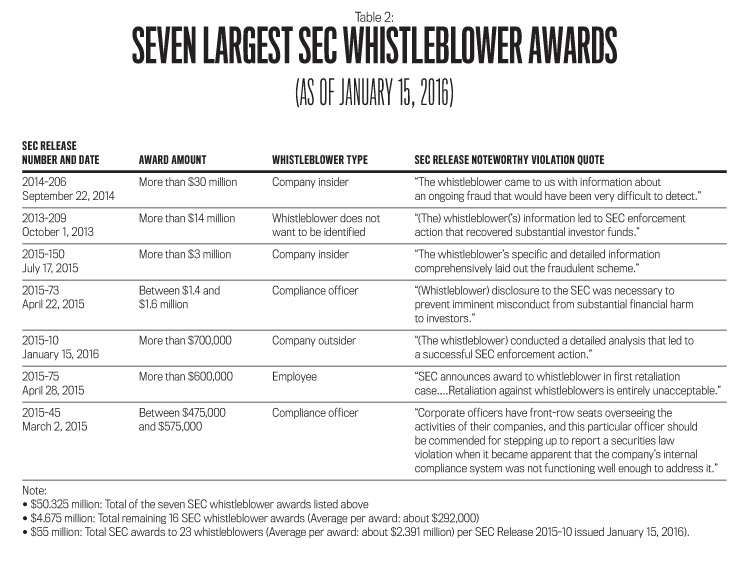

To see another indication of the high priority the SEC places on its whistleblower program, look at Table 2 for information about the top seven whistleblower payouts so far. Certain information, such as the whistleblower’s name, may not be publicly available. As the SEC has noted, “By law, the SEC must protect the confidentiality of whistleblowers and cannot disclose any information that might directly or indirectly reveal a whistleblower’s identity.”

On January 15, 2016, the SEC announced that the whistleblower program “has paid more than $55 million to 23 whistleblowers since the program’s inception in 2011.” This results in an average whistleblower payout of about $2.91 million. But the largest three awards totaled about $47 million. Additionally, the next four largest awards totaled $5.325 million. So if you exclude the seven largest whistleblower awards (listed in Table 2), the remaining amounts are $4.675 million in total awards paid to 16 whistleblowers. That’s an average of approximately $292,000 per award.

WHAT SHOULD COMPANIES DO TO ESTABLISH GOOD POLICIES?

The data presented in this article shows that the SEC Whistleblower Program has been successful and continues to expand. Enforcement actions have been backed up with large monetary sanctions, and SEC Chair White revealed that “we at the SEC increasingly see ourselves as the whistleblower’s advocate.”

The SEC Whistleblower Program will continue to impact CFOs, boards, audit committees, and the management of public companies. But what should CFOs and others charged with corporate governance do right now?

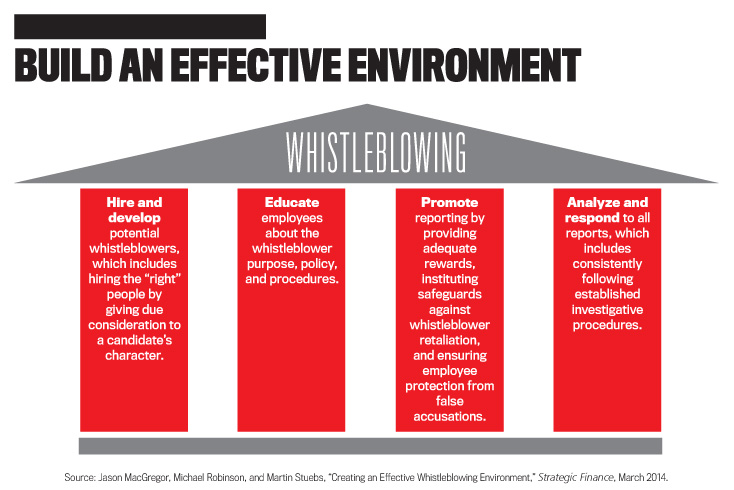

First, ensure that your company has proper policies and procedures in place. (see “Build an Effective Environment”). To avoid enforcement action under the SEC Whistleblower Program, your company must establish an effective company whistleblower policy and reporting process, including anti-retaliation protections. The company must communicate the program’s goals, policies, and procedures broadly and regularly to employees. Everyone at your firm must consistently follow the program, which means that it must have solid support from senior management and the board.

The anti-retaliation provisions (see “Prevent Retaliation Damage”) must be clear and strict, especially considering the SEC’s recent first-time enforcement action involving retaliation against a whistleblower. The SEC’s “2015 Annual Report to Congress on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program” aptly notes that “if individuals are not assured that they will be protected from retaliation if they report internally, they will be less likely to do so, which could undermine the important role that public companies’ internal compliance programs play in helping the Commission prevent, detect, and stop securities law violations.”

Second, establish an effective, responsive internal compliance program. The important first step of that process is for public company boards and management to conduct a thorough assessment of both the design and operation of existing internal compliance programs.

White indicated in her 2015 speech to the Garrett Institute that public companies should “build truly effective compliance programs to foster atmospheres where internal compliance reporting is not only tolerated, but actively encouraged. To that end, companies should take a hard look at whether their boards and senior management are promoting these priorities.” She referred to a survey of 2,500 executives worldwide that revealed as few as 7% of companies feel whistleblowing is important and that 44% either don’t have whistleblower policies or fail to publicize them. Also, we can’t overstate the importance of timely follow-up on internally reported concerns. CFOs and their firms should also carefully consider recent SEC first-time enforcement action involving whistleblowers who included company compliance and internal audit personnel and a former corporate officer.

Third, CFOs and others involved in governance should examine confidentiality and other agreements to make sure they don’t include language that restricts SEC whistleblowing. Any new contracts should also exclude such language. The SEC’s 2015 report indicates that the Office of the Whistleblower focuses on “whether employers were using confidentiality, severance, and other kinds of agreements to interfere with an individual’s ability to report potential wrongdoing to the SEC.” As noted earlier, Rule 21F-17 under the Exchange Act protects an individual’s unimpeded right to report possible securities law violations to the Commission.

Some of SEC Chair White’s comments to the Garrett Institute provide an appropriate conclusion to this article: “The bottom line,” she said, “is that responsible companies with strong compliance cultures and programs should not fear bona fide whistleblowers, but embrace them as a constructive part of the process to expose the wrongdoing that can harm a company and its reputation.” By following our suggestions, CFOs and others can address the latest developments in a positive and productive way.

March 2016