This isn’t surprising. Studies often show that 70% of mergers don’t live up to their promises. How can this happen? And why does it happen over and over again?

It has become increasingly common for companies to attempt mergers or acquisitions that are expected to have a huge impact on ongoing business operations and financial performance. For very large companies, these can be in the tens of billions of dollars. For smaller companies, they are often in the tens or hundreds of millions or even billions.

Similarly, companies often make capital investment decisions that are transformative with significant long-term financial implications, such as a new facility or a large expansion of existing operations. The company’s senior leaders will likely have completed extensive due diligence and have coherent and persuasive arguments for why the projects should be funded. Often, though, just like many mergers and acquisitions, these mega projects also fail to meet expectations and projections and then fail miserably. Many times they are failures of the senior leadership, including business unit leaders and financial executives. But they are also failures on the part of the board of directors (see “Mega Projects and an Active Board”).

ACTIVE BOARDS ARE CRITICAL

We often describe corporate boards of directors as having three primary roles and responsibilities: (1) strategic oversight, (2) accountability, and (3) senior-level staffing and evaluation. Though all three are important, this article will focus solely on the board’s role of strategic oversight. Managers have primary responsibility for the formulation and implementation of corporate strategy. But boards have significant responsibility for the review and approval of strategic plans and systems, for risk management policies and practices, for performance evaluation, and for major capital investments. (For more information about the role of boards, see “Corporate Governance Is Changing: Are You a Leader or a Laggard?” by Marc J. Epstein and Marie-Josée Roy, Strategic Finance, October 2010.)

After the Enron failure in 2001, a colleague and I extensively examined the company’s rise and fall and the critical role of the board of directors in the failure (see Steven C. Currall and Marc J. Epstein, “The Fragility of Organizational Trust: Lessons From the Rise and Fall of Enron,” Organizational Dynamics, Spring 2003). In our conclusions, we identified the numerous breaches of responsibility by and fiduciary duty of the board of directors. In the Enron case, the board relied too much on the opinions and analysis of CEO Kenneth Lay and the rest of the senior leadership team. Boards have a responsibility to provide independent analysis and deliberation of decisions and to be fully prepared to act and deliver effective strategic oversight.

In our analysis, we also described in detail the excessive trust that the board placed in the executive team. Trust in the team that the board has hired to manage the enterprise is critical, but excessive trust is misplaced. Excessive trust often leads to lax oversight of corporate activities and senior leadership decisions. Board responsibility for strategic oversight is necessary for the enterprise to function effectively.

The reports about the Enron board after the collapse showed that it took direction from the CEO. Votes commonly were unanimous, and discussions and debate often were minimal. If you think about most organizations in which you are involved, when votes are taken on issues, the vote may be 80/20 or 70/30 or even 50/50. But it is seldom unanimous! Usually there are various opinions on the appropriate actions to be taken. If board members are truly independent, and if they are thorough in their analysis of the issues, fewer votes will be unanimous.

Boards can’t be passive. When boards aren’t active, oversight is weak, and the risks to the enterprise that result from poor decisions and weak management and operations are common. For large project investments and for mergers and acquisitions, it isn’t just about regular due diligence or just about the price. Often there’s a question of whether the company should be doing the deal at all. And this isn’t just a decision for the CEO but for the entire board of directors. As part of its culture and as part of its relationship with the CEO, the board must ask the tough questions; challenge the data, the analysis, and the assumptions; and probe extensively to determine whether the deal is worth doing and likely to increase shareholder value.

Too often that isn’t the case.

Going along with the CEO’s wishes isn’t what corporate governance is supposed to be. The board, on behalf of the shareholders and stakeholders, hires the CEO to manage the operations of the enterprise. But the board also has the responsibility of providing oversight of CEO and senior management decisions. Though boards certainly shouldn’t micromanage, good governance does require independent and critical reviews by the board and intervention when the board disagrees with major decisions and direction of the senior leaders.

Successful board/CEO relationships are built on cooperation and collaboration while maintaining independence. The relationship must be established based on an understanding that there will be disagreements between the CEO and the board. The board provides oversight and makes decisions based on its responsibilities to represent stakeholder interests. Sometimes those decisions will differ from the CEO’s decisions. That doesn’t signal a lack of trust or support for the CEO. Rather, it’s only a disagreement over a particular issue—whether of strategic direction, staffing, accountability, or a capital investment project or merger proposal. If based on cooperation, collaboration, and mutual trust, CEO and board relationships are healthier and more successful when the board is active and fulfills its strategic oversight responsibility effectively.

INDEPENDENT CONTRARY OPINIONS ARE NECESSARY

As an essential part of their strategic oversight of large capital investments in mega projects and mergers and acquisitions, active boards often want to bring in external experts to provide guidance. Though accountants and lawyers are always part of the due diligence, too seldom are others brought in for the strategic aspects of the deal. This is the case whether the project or merger is proposed by the CEO or by a business unit or functional leader. Yet differences do exist.

Merger discussions often begin with a discreet meeting between the CEO of a company that wants to acquire another company and the CEO of the potential target company. The CEOs might agree, in principle, on a deal subject to both due diligence and board approvals. Next, the analysis is completed by the senior management team, approved by the CEO, and presented to the board. The problem is that often the analysis of the potential risks and uncertainties is incomplete. To avoid adding more companies to the lists of unsuccessful deals, such as the AOL-Time Warner and DaimlerChrysler mergers, independent contrary opinions are needed.

In the case of a CEO-initiated merger or project, senior managers are often reluctant to provide critical comments or oppose the deal. When the managers do provide comments, they are often cautioned that the CEO wants this deal or that others with more experience or insight have already analyzed the concerns and determined that the risks are minimal. Even when merger discussions emanate from initial analysis or discussions from a business unit or functional leader, the CEO will get on board and support the project so it will go forward. Then others in the organization might find it difficult to argue effectively that the deal shouldn’t be done.

Yet the deal must be challenged, both at the senior management level and at a board of directors meeting, before it’s approved. Given the internal organizational climate that often exists to resist thorough and effective debates, independent and external contrary opinions are critical. Though they include due diligence and reviews of existing analysis, external reviews also include a careful analysis of the basic assumptions; strategic fit; changing social, environmental, and political factors; considerations of alternative views and decisions; and far more. If companies are to avoid bad deals, they need to look carefully at why a deal might go bad and why a different and more complete approach to analysis and board consideration is necessary.

Many companies have certain industry or geographically specific issues that must be considered. For example, multinational corporations in the natural resource exploration businesses—such as mining and oil and gas—have additional challenges that demand independent contrary opinions. A few years ago, a large U.S. multinational was evaluating a potential joint venture in a country that demands that a local company have 51% ownership of such ventures. This creates a joint-venture partner risk in addition to numerous other risks. Further, a large number of natural resource investments are in countries that are politically unstable or have unfriendly regimes. So this very large potential investment could implode because of social, political, and legal issues in addition to the more common financial issues that are examined.

International consulting and global political risk consulting firms (like Kissinger Associates and Eurasia Group) can provide critical analysis and recommendations for potential large investments. In the case of the U.S. multinational, the instability of the government was certainly an issue in addition to the joint-venture partner risk in a country where courts might be biased. As it turns out, though the government wasn’t overthrown, the joint-venture partner didn’t perform as promised, and the company had little recourse and lost most of its investment. In investments in countries with potential changes in government through coups, outside contrary opinions can change the course of board decisions.

How can these big issues be missed? It happens all the time! Often a company and its CEO have significant time and reputational capital invested in a deal. Sometimes other factors are motivating the deal. But potential conflicts often exist that cloud the decisions, and an independent board analysis is the only thing keeping a bad deal from occurring. This often happens even when the proposed investment is coming from a business unit or functional head. Potential individual gains and significant organizational or interpersonal relationships sometimes inhibit the careful and rigorous analysis and discussion of views that may conflict with those of the CEO, other senior leaders, or the board. With an active board and the consideration of independent contrary opinions, these deliberations can be improved significantly. Then the mergers, the corporations, and the shareholders are all better off.

HOW TO INTEGRATE CONTRARY OPINIONS INTO DECISION MAKING

What techniques can companies use to do this? Some companies have adopted approaches that the military has used to integrate alternative analysis into decisions. One of these is “red teaming,” viewing a problem from an adversary or competitive position. Red teams challenge aspects of a company’s plans, programs, assumptions, and more. Boards of directors can use red teams to provide contrary analysis and opinions to the blue team (executives who are proposing a deal). The red teams attack, and the blue teams defend. By viewing a deal from the adversary’s or a doubter’s perspective, an alternative analysis of the likely merger success can be revealing. The red team provides a compelling case as to why the deal shouldn’t be done. The executives (blue team) continue to provide their compelling case why the deal should be done.

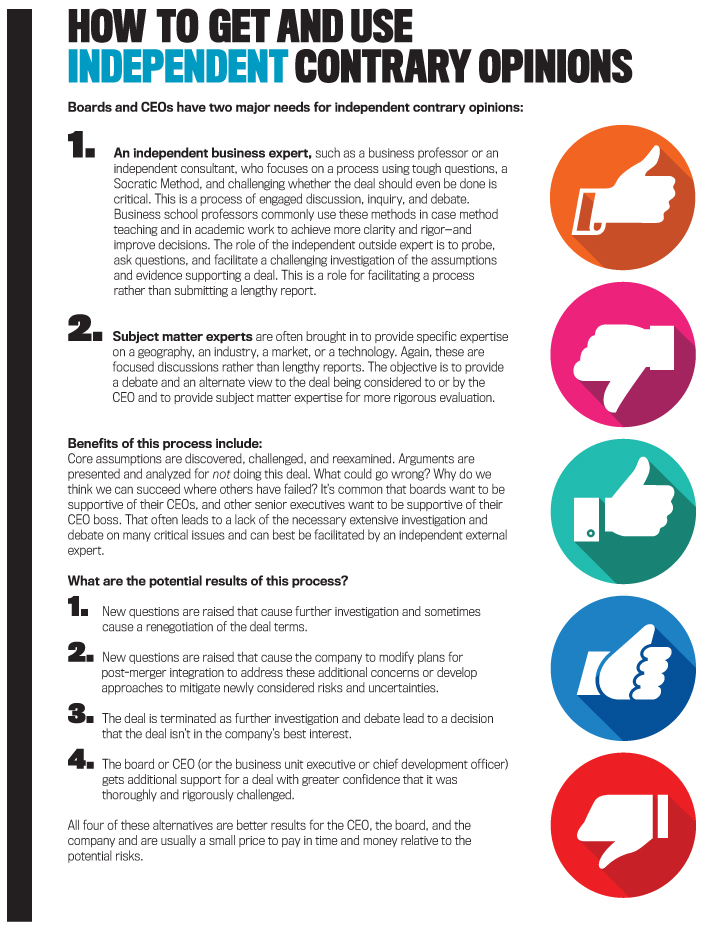

This process can be used when a business unit or functional head presents a deal (including a merger/acquisition, project, or other investment) to the CEO or when a CEO presents to the board of directors. For a relatively small deal, this process can work effectively and can be staffed by an internal red team. For larger deals that will be presented to the board, external and independent contrary opinions are needed. In each case, this process is trying to more carefully examine the thinking, consider what could go wrong, and avoid surprises.

In the military setting, the red team not only will do the critical and alternative analysis, but it will also provide suggestions of countermeasures and potential mitigation efforts that can be applied. In a business setting, the contrary analysis and opinions often prompt new approaches to making the deal and to the post-merger integration processes and mitigation of risk if the deal proceeds to completion. This usually provides rigor and clarity that improve the presentation to the CEO and then the presentation by the CEO to the board.

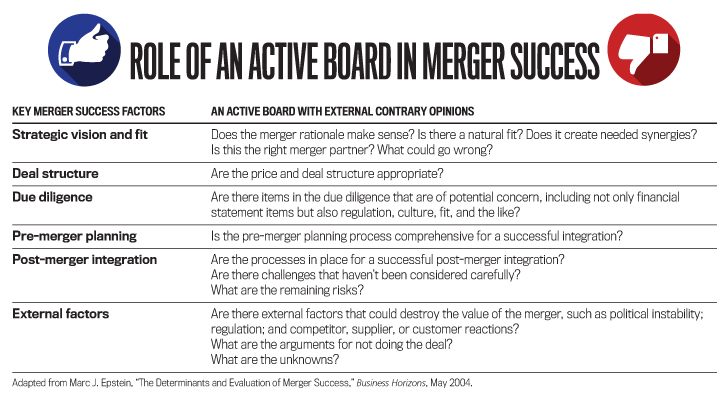

Six widely accepted merger success factors are often included in any analysis (see “Role of an Active Board in Merger Success”). Some of the questions that an active board or CEO might ask to make a better decision—or that a red team might provide answers to with the goal of improving the decision-making process—are listed next to each success factor. In all cases, obtaining contrary, independent opinions and using a Socratic Method that relies on deep, probing questions is critical. What are the arguments that experts would provide for not doing this deal? What could go wrong? Sometimes internal capacity does exist to complete this process internally. For large deals, bringing in outside experts is essential for good governance and to reduce the likelihood that bad deals are done. It is also critical so that active boards can fulfill their role of strategic oversight effectively.

It’s important that the contrary opinions are independent and external. Both the process and the content of the analyses must be rigorous and thorough. Deep, probing questions are necessary. Though these can be completed by internal senior leaders or board members, there are often social and political organizational antibodies that make this difficult. It requires significant expertise in content but especially in process. Master of Business Administration (MBA) classes often are conducted largely using the case method of teaching and rely heavily on the Socratic Method. This involves asking challenging questions and probing deeply to bring more rigor and clarity into the analysis and discussions. Similarly, discussions in corporate boardrooms (and in the discussions inside the corporation that precede those) must be structured to elicit the kinds of analysis and debate that lead to improved decisions. Rigorous, challenging debates that rely on careful and thorough analysis must be part of the presentation and discussions of contrary opinions. Alternative analysis and red teaming can be used, but participants must be careful that the critical analysis of the issues is independent and that the process is probing and critical.

This approach can be used for new facilities, joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, and other investments in large and small companies. The external and independent contrary opinions usually will be included only on larger deals (relative to company size), but the approach can be used selectively on all deals and with companies of any size. Through this process, senior management teams and corporate boards can improve deal performance significantly.

THE ROLE OF THE FINANCIAL EXECUTIVE

Financial executives are taking an increasingly active role, not only in matters of accounting and financial management but also in the leadership and governance of the corporation and as key players in the C-suite. Often much of the due diligence of mergers and acquisitions and proposals for other large capital investments is dependent on the analysis of the financial executives.

There’s a need to challenge the data. And there’s a need to broadly define the internal control function and rigorously investigate the broad set of factors that lead to successful mergers. Sometimes that places the CFO in direct conflict with the views of a business unit or functional head. Sometimes the CFO’s analysis shows deficiencies in the CEO’s analysis. Boards of directors have the responsibility to review and approve large transactions and provide strategic oversight. That can’t be accomplished effectively without the support of diligent financial executives and independent contrary opinions to ask the really tough questions and challenge merger proposals to ensure that they are vetted and evaluated adequately.

The use of external independent contrary opinions, such as red teams, in internal deliberations among the executive leaders can be useful for small deals. The use of this approach for large projects or merger deals that require board approval is essential. Board deliberations and the role of financial executives in those deliberations must rely on rigorous analysis supported by the Socratic Method that asks really tough questions about whether the deal is really worth doing. The financial executives can provide some of the analysis and facilitate an independent analysis and synthesis of critical issues. In this way, CFOs and other financial leaders can significantly reduce the likelihood that big mistakes are made and really bad deals are done—and they can make sure that their companies won’t be discussed in the same way AOL-Time Warner and DaimlerChrysler are. Also, observers won’t be asking “What were they thinking?”

January 2016