But finance and accounting leaders aren’t the only ones facing this pressure. Those in human resources (HR) and information technology (IT) are in similar situations. This shared need creates a potential opportunity: The primary administrative services common to virtually all modern organizations—including finance and accounting, IT, and HR—can work together synergistically. This transformation from a traditional, functional paradigm will result in a more strategic, customer-focused, and cost-effective structure for the benefit of the organization as a whole and its stakeholders.

THE PROBLEM

How can today’s finance leaders meet this expectation in the most efficient and effective way? Finance transformation initiatives generally involve four elements:

* Leveraging highly effective enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems;

* Centralizing and automating the most routine aspects of finance and accounting services;* Standardizing a variety of business-decision-support capabilities, such as financial planning and analysis (FP&A), and consolidating their location; and

* Streamlining activities at corporate headquarters.

Yet financial transformation is only one aspect of the broader contemporary business transformation under way. How can businesses optimize the significant investment in transformation without systematic coordination with the transformation strategies of IT and HR? Aren’t these groups mutually dependent, particularly in the eyes of our internal customers? The situation is akin to a railroad, where the proper functioning of the trains, tracks, and signals reflects the interdependencies of these three functions. If any one of them fails, the whole system can fail, leading to disaster.

So why haven’t more companies moved toward implementing an integrated strategy and coordinated administrative services? Some larger businesses actively and systematically rotate managers across administrative boundaries, but this is more the exception than the rule in the current environment. More likely is the type of functional boundaries that many management gurus railed against during the last major recession: silos. An individual who enters a company in one of the three major administrative functions is likely to stay in that silo for the rest of his or her career.

This creates weaknesses and limitations that make it more difficult for employees in a functional area to assist and become better partners with those in other areas. When we speak with human resource professionals, who are often labeled “generalists,” they are frustrated, feel compromised, and sometimes are even insulted that they are asked to understand basic concepts of finance, accounting, and IT to be more effective in their jobs as “partners.” For example, can your HR support person define a basic business term like “free cash flow”?

We also hear from IT people who develop and run application programs rich in accounting and finance content but who have a very limited sophistication about the business decision-making context reflecting their internal customer needs. This deficit in business literacy often impairs their ability to serve.

And those working in finance and accounting are often some of the best subject-matter experts, but they also can make for some of the worst people managers and communicators within the organization. Employee “climate” survey results show that finance and accounting supervisors are often viewed as “clueless” with respect to the expectation that they provide timely, candid feedback to their direct reports. It should be noted that the number one reason cited by high-potential staff for leaving their organizations is the poor supervisory skills of their immediate superior.

A related characteristic common in many organizations today is the dysfunctional or suboptimal relationship between finance, HR, and IT. The related mutual distrust (which in itself could be a consequence or side effect of functional silos) serves as a convenient excuse for poor-quality services, cost issues, and an inability to address and solve enduring performance problems. Consider these anecdotal illustrations based on comments from executives within each function:

IT: “Those folks in finance signed off on everything the Enterprise Resource Planning software provider and their consultants wanted. Of course, they never asked us if we had the bandwidth to implement effectively—they seem too close to the consultants to be objective.” Many in the IT culture don’t share the business school backgrounds common to other administrative managers, which can create a chronic disconnect between IT and other administrative staff. Their world has undergone a series of increasingly dramatic revolutions in technology that are exciting and daunting at the same time.

With the advent of personal devices and programs that are both very user-friendly and highly functional, the pressure is increasing on company information systems to reflect a similar level of intuitive use and quality of content. This is the first generation where the quality of technology in the home and personal space leads the quality of technology in the office.

HR: “Finance and IT folks provide us with little useful guidance with respect to the competencies, skills, and personality features that they really need to build their future teams—but they direct us on which schools to target for recruitment.” Former GE CEO Jack Welch believes that many business leaders undervalue the work of HR and that they don’t provide those in HR with the stature, resources, and talent needed to drive and sustain business practice excellence. In March 2009, Jack and Suzy Welch wrote in BusinessWeek, “We’ve said it before: HR rarely gets enough emphasis. At times like these, it becomes obvious how few companies get it right.”

In contrast, a March 2009 CFO.com story reported on Rutgers University professor Richard Beatty’s general session at a CFO Rising conference. Beatty suggested bypassing HR in many hiring situations and noted that while “the language of organizations is numbers, HR isn’t very good at data analytics….They don’t think like business people. Many of them entered human resources because they wanted to help people, which I’m all for, but I’m also for building winning organizations.”

Conditions haven’t changed much in the years since these views were expressed. Regardless of which view resonates more with you, the time has come to end HR’s role as the Achilles’ heel of management.

Finance: “I have not gotten the kind of responsiveness that I need from HR, so I have my own HR training operation to support me. They seem to avoid ‘technical’ learning needs like the plague. And IT, don’t get me started. Their internal pricing is prohibitive, and I am not allowed to go outside. They promised me a better system, but all I know is I still can’t get reliable, timely sales data. This makes us all seem incompetent!” It isn’t unusual to find finance leaders who are frustrated with the quality of “service and support” they receive from the IT community—whether that support is outsourced or in house. For example, the very large, cumbersome, and costly ERP systems have yet to deliver on their return on investment (ROI) promises for many. It also is worth noting that some companies are challenged to provide significant development opportunities for high-potential performers and key players. There are fewer chances for these individuals—who often crave challenges and need them to thrive—to find high-value development opportunities outside their function.

Many pressures confront corporate administrative services, their managers, and leaders in today’s context (See “11 Common Pressure Points”). The complaints from these executives appear almost ironic given that all three corporate administrative services face similar challenges. In essence, we have become conditioned to expect that corporate administrative functions don’t work together—and in some organizations, it’s accepted that there is a virtual undeclared war between the finance and accounting, HR, and IT functions. It’s very unlikely that these important and mutually dependent business-support elements can deliver high-quality, efficient, and effective services in an environment of significant mistrust and discord.

Experience from past recessions and economic downturns has shown us that lean times can lead to valuable innovations in business practices that result in a significant, scalable, and sustainable competitive edge. As the old adage goes, “Necessity is the mother of invention.” Given the current economic uncertainty, it’s our hope that the greater necessity for survival will drive business leaders to challenge the assumption of, and tolerance for, this dissonance and consider addressing it as a critical element of a successful transformation strategy and plan.

FUNCTIONAL INTEGRATION

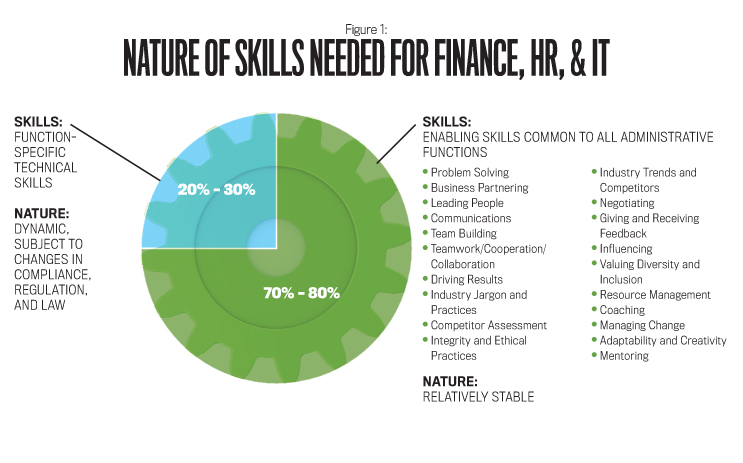

A focus on the skills needed to perform in the administrative area will bring about insight to help achieve the transformational goals. In some of our early research in skills assessment and management with leading companies in a variety of industries, it became very clear that about 75% of the skills and competencies common to finance and accounting job families were also common to other administrative functions (see Figure 1). For example, who can deny that project management, influencing, time management, business acumen, and productivity skills are equally important across all administrative functions?

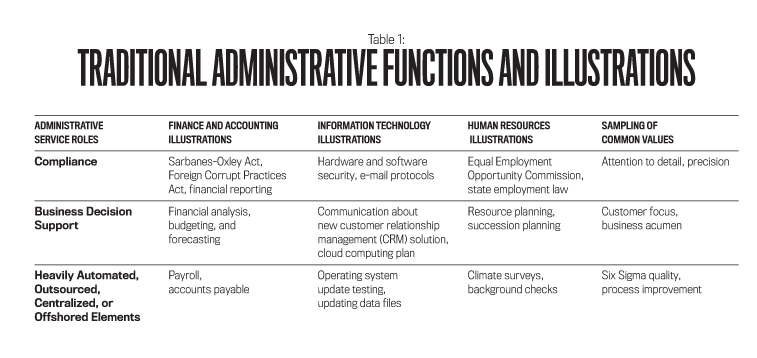

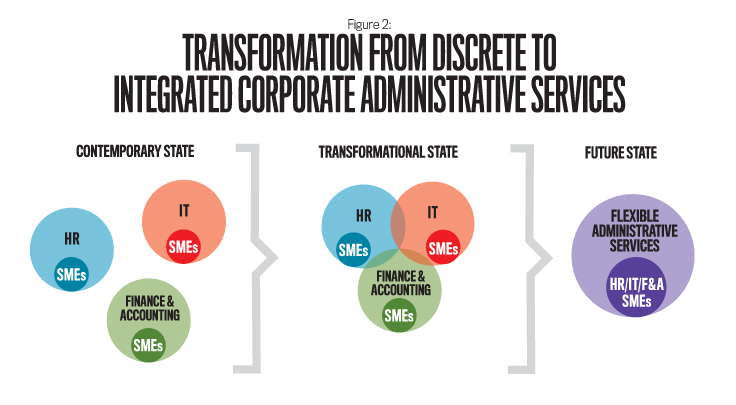

Figure 2 illustrates the functional transformation process that needs to take place. Although we may think of finance and accounting, IT, and HR as quite different, each possesses similar key components: compliance, business decision support, and heavily automated elements. From a skills perspective, it would seem that these traditional functional elements of administrative services have more in common than may be generally believed. Table 1 shows the relationships between the three primary components of administrative services.

In terms of workforce agility, the development of flexible administrative services staff would improve morale and create new cost savings and productivity gains. For example, during a period when a company is growing through acquisition and new due diligence work is needed in the short term, this administrative workforce would flex to accommodate these short-term work assignments, obviating the need for expensive, less-productive outside services. Or, during systems upgrades, the company could deploy the flexible workforce to support systems implementation. This would reduce the reliance on pricey outside service providers, build internal self-confidence in the new systems more quickly, and result in the type of learning transfer that is often promised by the advisory camp during the initial engagement “sell” phase yet rarely delivered in the end.

One requirement to enable this transformation and realize its benefits will be a greater, more aggressive focus on talent management. Talent management will evolve from a “nice to have” to the company’s strategic distribution channel for intellectual capital, competencies, and skills where and when they are needed.

With the 75% of shared skills covered, each functional area will need to focus only on being able to cover the remaining 25% of skills—the technical skills unique to each functional group. That means about 25% of functional roles will retain the status of being a subject-matter expert or individual contributor—for example, the company’s transfer pricing expert; ERP systems strategist; and equal employment opportunity compliance roles. Top performance in these roles is and will continue to be critical for long-term organizational success.

EXAMPLES IN PRACTICE

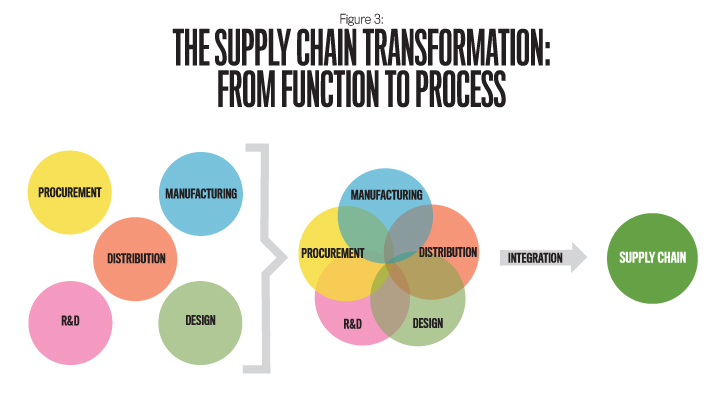

There are business examples where efforts have followed at least the spirit of a functional integration approach. In the recent past, many respected companies embraced the supply chain approach to better meet customer expectations, streamline operations, and reduce cost. This movement to supply chain management brought together previous separate, culturally distinct, and independent business functions such as procurement (sourcing), manufacturing, distribution (logistics), research and development (R&D), and design (see Figure 3).

Before moving to a more integrated approach for satisfying customers, the individual functions had suboptimal and often dissonant relationships that prevented them from realizing the business performance excellence that the functions knew was in their collective best interest. It’s our belief that the company administrative functions can be integrated in a similar fashion and, if executed properly, would yield similarly sustainable and substantial advantages in both cost and service quality.

Another business example can be seen in the operations of many smaller entrepreneurial businesses. The mix of administrative responsibilities for a business manager in the small business environment often tests the boundaries of traditional job families and functional classifications common to larger organizations. For years, we have regularly witnessed streamlined, responsive performance from small businesses that outstrips larger competitors and provides the foundation for profitable growth.

A third example can be found in the early-career training program developed for a category-leading retailer. The Business Leadership Development (BLD) program provided an integrated framework for the early development and learning of future managers in administrative services, including finance and accounting, HR, and information systems job families. It was championed by the company’s CFO, who previously had been a finance executive at a company that had structured early-career leadership development programs organized by function. He felt those programs were fine but didn’t harness cross-functional potential.

Independent of college major, all BLDers were required to take their business practices coursework together across traditional functional lines and experience a series of six-month rotations that included in-store sales assignments, accounting and finance assignments, HR assignments, and information systems assignments. The objective was to develop a new generation of agile, flexible, and self-confident employees who—like triathlon participants who train and compete across three disciplines—could serve in a variety of roles across administrative services independent of their academic background.

Not only did the program encourage greater cross-functional involvement, but it also improved the overall quality of job candidates for the company—and at a lower cost than before. The primary reason for this positive change was the new, functional “boundary-breaking” career opportunities the retailer could offer. Folks early in their careers will often trade salary and benefits for robust career opportunities and acquisition of marketable skills. The BLD program is emblematic of this innovative vision of integrating administrative services from the ground up.

GETTING STARTED

Business and financial leaders should act proactively and creatively to take a hard, critical look at some of the functional paradigms and traditional assumptions within their administrative structure and administration. The following list includes several pragmatic steps to get started on this promising path:

- Begin a pilot six-month rotational program between Finance, HR, and IT for junior staff members who have been with the company for less than four years.

- Identify the most common nontechnical skills that are key to administrative services in your company and where the biggest performance gaps for each key skill lie.

- Align your training on nontechnical skills to meet the needs of Finance, HR, and IT, and deliver the classes to a mix of administrative services staff from each area. This approach will allow for additional “cross-pollination” between the functions.

- Communicate—in the context of recruiting new prospects—the benefits of your cross-functional rotation programs.

- Energize talented but “stalled” middle managers with two- to three-year rotations outside their functional boundaries.

- Demonstrate leadership buy-in and credibility by rotating selected senior direct reports of finance, HR, and IT executives across functional silos.

- Include representatives from other administrative functions in problem-solving meetings, even if the meeting topic doesn’t seem to require participation beyond the function. In the early stages of problem solving, most people don’t fully appreciate all the relevant dimensions of a problem—so it’s good to err on the side of inclusion. This will enhance relationships and improve understanding between the areas. And after an initial “learning period” while this integrated solution is being implemented, it will improve the quality, speed, and confidence in decision making.

- Promote and communicate the value proposition for moving in this specific direction. Subject to the quality of execution, it can be a win-win-win for leaders, staff, and customers.

In addition to these steps, one simple question should be considered: Beyond the finance transformation initiative, are HR and IT also concurrently pursuing their own transformation initiatives—each with its own business case, advisors, jargon, model, strategy, and plan? If the answer to this question is yes or partially so, there is a great opportunity to, at a minimum, coordinate, communicate, and align these initiatives.

Most of the companies that we recently interviewed have moved ahead with their transformation initiatives using plans that don’t resonate with the premises of the transformation value proposition, including the key benefit of standardization. This uncoordinated, balkanized approach is costly, doesn’t leverage the collective intellectual capital, and increases the risk of not achieving its goal given the reality of functional interdependence.

The promising news is that other companies are already reaping the benefits of this approach in the context of highly effective and efficient shared service centers (SSCs) where both leaders and staff movement between finance, HR, and IT support roles are driving improved performance and productivity. Having moved well beyond the lowhanging fruit of transaction processing automation, these trailblazers are increasingly bringing work into the SSCs that was traditionally executed by HR, IT, and other functions. The commonality of management and staff skills required in the SSCs across a variety of functional applications has led to new organic growth in talent movement across traditional lines. This movement, which represents a real and welcome departure from conventional behavior, addresses some of the most significant SSC sustainability concerns, including staff acquisition, retention, and coherent talent development pathways.

We have the opportunity to study this important trend and apply what can be learned to enable positive, sustained change that spreads beyond the traditional boundaries that constrain entity performance and potential. The ideas we present here should provide a platform for the design and development of a new administrative design model that supports reaching new frontiers in performance, alignment, productivity, cost-effectiveness, and competitive advantage.

The authors are grateful to Colin Johnson, senior manager, Finance Functional Excellence with Eaton Corporation, and to Laura Masica, functions learning leader with Cargill, Inc., for their review and comments on an earlier draft of this article.

April 2016