Sometimes called financial forensics, forensic accounting is a skill set that uses accepted bodies of knowledge (such as laws of evidence, customary practices, and professional ethics) along with empirical data (for example, financial statements and nonfinancial metrics). The goal is to develop an expert opinion that’s helpful in resolving issues that can adversely impact commercial or other performance objectives. Forensic accountants work to understand evidence and determine facts in actual or potential conflicts of accountability, transparency, and integrity. They do so using reliable methods of inquiry (such as statistical techniques) and evaluative concepts (such as an organization’s code of ethics), which enables them to obtain credible findings.

The specialized knowledge and analytical skills that forensic accountants apply to financial, economic, and accounting problems can help companies discover and fix conditions that might be detrimental to their reputation or the bottom line. Forensic accountants offer problem-solving approaches that transcend check-the-box routines often used for traditional audits. Their experience in preparing reports in anticipation of litigation allows inquiries to proceed without inefficient duplicated, overlapping, and conflicting efforts. And perhaps most important, an ethical forensic accounting process is impartial, which increases the assurance of an effective outcome.

For their work, forensic accountants don’t necessarily need deep knowledge from long-standing practice as public accountants, although that experience can be helpful in resolving inconsistencies with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and other specific financial issues. But a forensic accountant’s scope of work is broader than a GAAP financial audit or verification of others’ statements. It’s applicable to other managerial concerns, such as financial crime risk, operational auditing, and performance auditing.

Forensic accounting is an applied art that people outside the organization may rigorously test, so it’s necessary to control the scope of work and apply ethical principles. Therefore, forensic accountants must adhere to professional, legal, and contractual standards to ensure integrity, competency, confidentiality, and privacy. Otherwise, the work of the forensic accounting team is at risk of becoming tainted, not persuasive, and not credible. It would frustrate the purpose of the engagement, which is to resolve potential or actual disputes effectively.

HELPING FINANCE LEADERS

Finance leaders such as the CFO or controller have complex roles. At the risk of oversimplification, their function can be broken down into material participation in routine transactions, such as internal control effectiveness, and in nonroutine transactions, such as mergers and acquisitions, as well as subprocesses (e.g., continuous internal audit programs), special projects, and conducting or updating background checks.

Companies generally design and implement these processes and procedures with some degree of success—at the very least, no actual notice of a material weakness or other significant dysfunction is received. That lack of notice, however, may lead some finance leaders to conclude that the existing procedures are adequate, and then they defer to the business judgment of directors and executive officers without rechecking anything or challenging the conclusion that nothing is wrong. Yet this presumption that all is working well because no complaint has surfaced is faulty. All may not be what it seems, and things can still fall apart.

Forensic accountants can be an effective, robust, and impartial counterweight to faulty presumptions. Because forensic accountants challenge operative estimates and assumptions, CFOs and controllers can use them to gain a kind of counterintelligence, reevaluating long-standing, established routines. Regularly using forensic accountants also is an economical way to prevent or detect rogue or collusive employee conduct causing hidden fraud. Foiling or finding those crimes requires a periodic fresh examination of conditions and developing new criteria to assess employee conduct risk. In some cases, CFOs and controllers may also have to think about providing court evidence covering noncompliance details, specifying “who, what, when, where, why, and how” information. Forensic accountants have the expertise to do that.

Forensic accountants can enhance a corporation’s internal audit function and its special projects. They also can improve an organization’s gatekeeping function, providing greater assurance of high-quality review and approval procedures that are superior to unenhanced programs. And their experience with corruption and fraud can be invaluable to a company developing and maintaining integrity programs.

Because the forensic accountants’ report must be suitable for a court of law, it is subject to adversarial cross-examination about its premises, conclusion, and methodology. In court proceedings, the report is exposed to the risks of publicity, transparency, and ethics. For example, the open hearing in court against an adversarial party can generate publicity. Because the report must meet an accepted standard for providing sufficient evidence, company details are more transparent. In addition, the court’s demand for impartiality makes stringent adherence to professional ethics essential. Therefore, these conditions must guide all aspects of forensic accountants’ inquiry procedures—including their nature, timing, extent, documentation, and communication. The result is more credible, higher-quality reporting.

That doesn’t mean that forensic accounting inquiries always result in transparent public reporting and the airing of dirty laundry. In cases where the forensic accountants are brought in for issues not involving litigation, companies can assure privacy, secrecy, and confidentiality by working with in-house and outside legal counsel to use nondisclosure agreements.

IDENTIFYING THE NEED FOR HELP

The signs that a company needs help from forensic accountants may be subtle at first. Circumstances and issues rarely begin fully developed and transparent. The CFO and controller are often challenged to work with information whose reliability isn’t reasonably certain, lending some ambiguity that calls for resolution. They may decide to use internal resources, outside forensic accountants, external independent auditors, or some combination of experts. They may even decide to do nothing. “When Do You Need Forensic Accountants?” (sidebar at the end of the article) provides a checklist of questions that can help determine when it might be time to call in a forensic accountant.

To illustrate the kinds of situations that might be relevant, let’s look at some fictionalized scenarios and recent newsworthy events to see how forensic accountants could have made a difference.

COMPOSITE SCENARIOS

The following four scenarios are composites of actual events. They realistically demonstrate the kind of ambiguous dilemmas CFOs and controllers often face. In the first two cases, finance executives properly deployed forensic accountants to solve the problem. But in the last two cases, forensic accountants weren’t brought in, and the problems got worse.

The kickback scheme. An anonymous whistleblower complaint alleged that a senior property manager of a publicly held real estate investment trust (REIT) was orchestrating a bribery and kickback scheme. The REIT responded to the allegation, but the CFO-led team didn’t have extensive experience in conducting criminal investigations. Therefore, the team sought the aid of independent forensic accountants who were experienced in conducting fraud examinations and related criminal inquiries. The forensic accountants discovered testimonial evidence and documentation demonstrating that the whistleblower’s complaint wasn’t supported. The forensic accountants’ investigation also found that the REIT’s response met applicable laws and regulations and that it complied with the REIT’s code of ethics. The investigators provided sufficient evidence to satisfy everyone involved, including the external auditors and law enforcement authorities.

Beefing up banking security. Customers at a foreign bank voiced concerns about online banking security. They also questioned the internal controls for employees inputting, accessing, maintaining, and updating customer-provided records. The issues involved were rather sensitive, and the CFO and his team lacked objectivity because they were involved in designing and implementing the control system. The CFO brought in forensic accountants who planned and performed the work needed to address the customers’ concerns. Because the forensic accountants were independent and impartial, they were able to obtain employee compliance information that the employees were reluctant to share with management.

Company investigators botch the job. A member of the board of trustees who was overseeing a multiemployer pension plan received a tip about potentially criminal improprieties in the plan’s accounting and financial reporting. To mitigate damage to the reputations of the board and those implicated in the scheme, the board delegated oversight of the inquiry to the CFO and the internal audit team. Their investigation failed to integrate and accurately interpret all of the documentary, testimonial, and public domain evidence—resulting in misleading conclusions that understated the likely criminal conduct of the fraudsters. A follow-up inquiry by the local prosecutor’s office confirmed that the company’s internal investigation lacked credibility.

Fraudsters intimidate junior investigators. A newly transferred employee for a publicly held financial services and trading company noticed that the organization was disregarding procurement policies and procedures, including documentation of compliance, in the development of a newly acquired real estate property. The timing of this discovery was less than propitious for the CFO-led team charged with reviewing and following up on the issues raised. The team had inadequate staffing and many routine reporting obligations, so the team members delegated much of the work to relatively inexperienced junior staff. Employees involved in the noncompliance scheme used subtle intimidation and other tactics against the vulnerable junior staff to suppress information. As a result, the findings of noncompliance were incomplete and failed to address the root causes. In reality, criminal corruption and self-dealing were covertly at play—which law enforcement authorities later discovered.

EVENTS IN THE NEWS

Forensic accountants’ expert skill in impartially gathering and analyzing evidence is valuable in many situations. Here are some recently publicized business stories where proactive use of forensic accountants might have prevented calamity.

GM ignition switches. In 2014, General Motors (GM) implemented a massive recall of vehicles because of faulty ignition switches. A formal dispute exists between GM and Delphi Automotive PLC, the company that manufactured the ignition switches. Documents suggest that GM may have pressured Delphi to supply GM with substandard ignition switches, which GM allegedly knew were a risk to public safety and not feasible to repair. An operational audit, including procurement process management, conducted under the guidance of independent and impartial forensic accountants would likely have discovered, interpreted, and used such documentary evidence to persuade GM senior management that applying such business pressure to a key supplier presented a hazard to both GM’s business reputation and to customers. Many lawsuits are pending against GM.

Takata airbags. Another well-known automobile controversy involves the dispute between Takata Corporation, a manufacturer of automobile airbags, and Honda Motor Company, its largest customer. Honda alleges that Takata knew its airbags were defective and posed a significant risk of death or serious bodily injury if they were deployed. A forensic-assisted operational audit of Takata would have likely discovered the internal communications, performance reports, and customer feedback about the airbags and thus rejected continuing the underlying practices without challenging such potentially unjustifiable and harmful practices before the highest governance levels of Takata.

The New York Federal Reserve Bank (NYFRB). Testimonial evidence discussed in U.S. Senate Banking Committee subcommittee hearings included concerns about the independence, operations, and regulatory practices of the NYFRB, including whether it provided potentially illicit assistance to a regulated financial institution. Allegedly, the NYFRB didn’t adequately appreciate internal communications from one of its examiners. As a result, the NYFRB didn’t detect and promptly remediate the underlying potential conflicts of interest issues. Often, the key assistance provided by independent and impartial forensic accountants is in the interpretation of the documentation, which they would use to build a persuasive argument to cease and remedy the underlying, potentially unsound business practices. Integrity and ethics don’t allow forensic accountants to worry about “rocking the boat,” an approach that sometimes causes internal auditors and examiners to temper their own well-founded concerns.

WORKING WITH FORENSIC ACCOUNTANTS

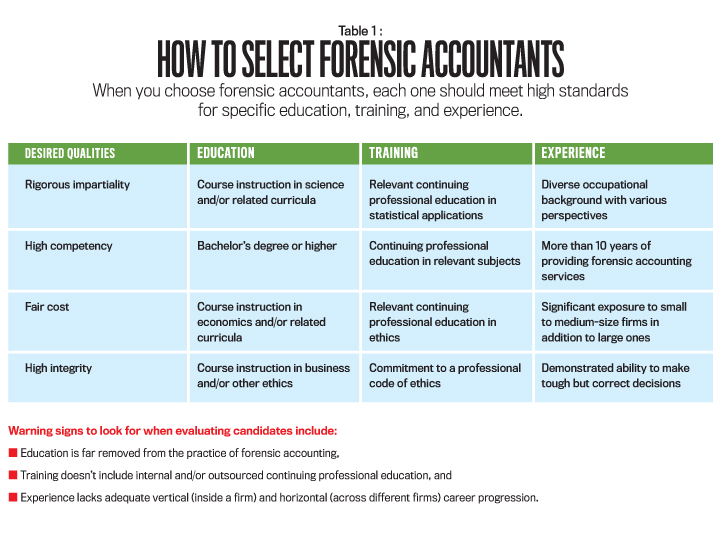

Though forensic accountants must meet certain standards of objectivity, proficiency, and ethics, they vary in experience, education, knowledge, training, skills, temperament, and personality—all of which are important in selecting a forensic accountant. Table 1 (see p. 50) illustrates in part how to vet forensic accountants, including some warning signs to watch out for.

Currently, there isn’t any robust and centralized public reporting or oversight of forensic accountants. Finance executives should consider exercising enhanced due diligence prior to engaging forensic accountants, ensuring that the candidates aren’t the subject of unpublicized malpractice lawsuits or state board of accountancy enforcement actions.

Once the actual engagement begins, CFOs and controllers should work closely with the forensic accountant. Their specialized knowledge about the company helps the problem-solving process. Here are some tips to help CFOs and controllers get the most out of working with forensic accountants:

- Tell essential staff—such as the in-house counsel, the IT representative, and the accounting manager—that you are considering hiring an outside forensic accountant. The staff can provide helpful feedback, recommendations, and cooperation. But make sure that none of the consulted staff members is directly involved with the underlying problem or issue.

- Before hiring anyone, do an in-depth interview with the prospective forensic accountants with three or more of your internal staff. Include those who will primarily manage and interpret the results of the accountants’ fieldwork.

- Consider whether enhanced due diligence of the forensic accountants would be cost effective.

- Obtain a detailed estimate of the scope and the cost of the proposed work, broken down by the different phases of the engagement—for example, planning, initial fieldwork, follow-up fieldwork, report drafting, and so forth. Do that before allowing an army of forensic accountants to start the meter running.

- In the letter of engagement, strictly limit the amount of time allowable for updating, report writing, and other functions not directly related to examining documentation and other evidence. The letter should also include the option, exercisable by the client, to obtain only an oral report.

- Insist on having only a small number of high-level forensic accountants begin the preliminary inquiry, instead of an army of accountants. Starting with only one accountant may be sufficient.

- Obtain a list of the types of information required—but not a document production request list. The internal project leader or liaison may be able to provide the required information in a more economical and efficient manner without strictly adhering to the document production list.

- To the extent it’s practical, provide an internal work area within which all of the forensic accountants will work. The area should include computers, secure and controlled Internet access, and so forth.

- If feasible, require that all of the forensic accountants stay on company premises during the entire workday, and provide lunch for them. That will accelerate their progress.

- Insist on having daily end-of-day updates from the appropriate high-level forensic accountant. Require that the highest-level forensic accountant with firsthand knowledge of the preliminary inquiry does the updates. You don’t want updates from a partner-in-charge who doesn’t directly supervise the field work.

- Obtain weekly itemized statements of professional fees and reimbursable expenses.

It’s important to develop trust and teamwork among everyone involved in a forensic accounting project, but there’s a risk that careerism or personal issues will cause team members to have differing goals. That’s why CFOs and controllers must carefully inspect and oversee the process.

AN UNDERUSED RESOURCE

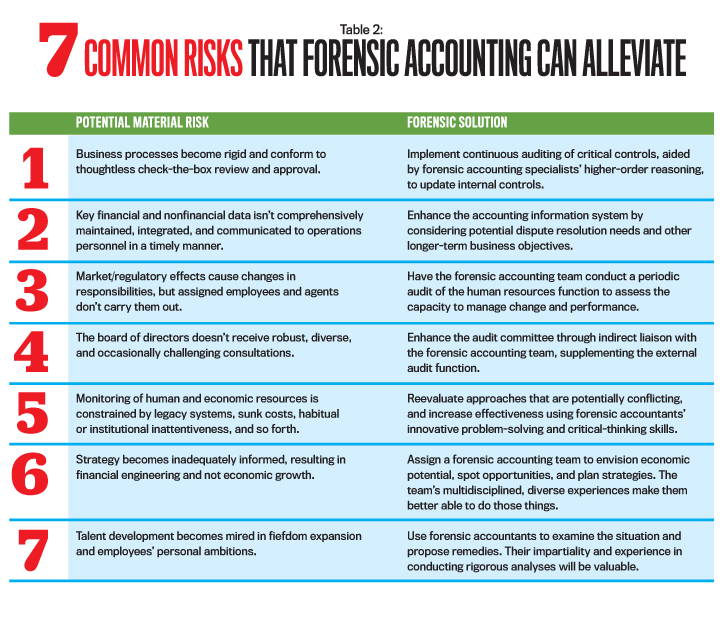

Forensic accountants are an underused resource in business. CFOs and controllers who only use forensic accountants for audits are neglecting their many other uses, including their ability to resolve some critical challenges that many companies share. Table 2 lists seven common company risks and the possible solutions that forensic accounting can provide. In this age of increasing change and threats, using forensic accountants more frequently may be a strategy whose time has come.

SIDEBAR: WHEN DO YOU NEED FORENSIC ACCOUNTANTS?

CFOs and controllers must ask some special questions to determine if they need help from forensic accountants.

Have you received information suggesting either of the following scenarios?

- An account at an independent party (for example, a service provider) doesn’t reconcile with an internal account, especially where cash transfers are involved.

- A person associated with the company (for instance, an employee or an agent) is the subject of a whistleblower report, tip, or other communication involving events that potentially increase fraud risk—such as financial loss resulting from a divorce.

Any information that casts suspicion on the integrity of accounts or individuals responsible for them can be a good reason to consult forensic accountants.

Has your organization established a well-designed, routinely implemented, continuous internal auditing process? Is either of the following conditions applicable?

- The company doesn’t subject critical controls to an audit frequency of being audited every month for six months, then at the third-quarter and fourth-quarter ends.

- Turnover for internal audit people is either high or low. That’s a danger signal, even if they are outsourced. Is institutional knowledge adequate for those who have been with the company for less than three years? Has the internal audit leadership and team been the same for more than 10 years? If so, they can become reluctant to change standards and examinations as internal and external conditions change.

A potential audit function deficiency or less-than-optimal structure and process may be sufficient cause to consult forensic accountants—even without specific incriminating information.

How well does your organization handle risk management? Is either of the following conditions applicable?

- The risk of false positives (for example, a finding of fraud where there is none) discourages innovative internal auditing.

- The risk of false negatives (for example, a finding that fraud hasn’t occurred where in fact it has occurred) is underappreciated because it creates discomfort or challenges existing resources.

Forensic accounting brings a fresh perspective to risk management. Therefore, a failure to include forensic accountants in the risk management process, especially in assessing fraud and conduct risks, may be the most common serious oversight.

September 2015