Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

The result is that all levels of decision makers are denied the mission-critical information they need to manage organizations, make good decisions, and improve performance. Yet management accountants are supposedly expanding their role and supporting the executive team as strategic advisors. Is the hype actually just a fantasy created by management accountants?

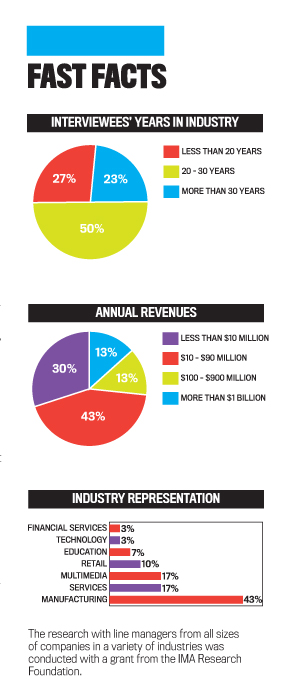

To answer this question, we’ll examine six areas in which decision makers are concerned about the work of management accountants. We’ll share information from users who are frustrated and disillusioned by the inability of accountants to provide them the insights and foresight to improve their organizations. And we’ll describe some relatively obvious solutions to resolve the deficiencies. This information is based on our years of experience in management accounting and finance and on interviews we conducted with line managers from all sizes of companies in a variety of industries. Although it’s going to seem like the purpose of this article is just to criticize management accountants, our intent is to motivate and inspire them to truly be the strategic advisors they are supposed to be.

The issues in this article don’t involve financial accounting. They involve management accounting. Financial accounting is used for regulatory compliance and following rules to satisfy needs of the investment community. Its purpose is for valuation, and external audits assure the rules are followed. In contrast, the purpose of management accounting (in addition to keeping the books and performing a variety of financial transactions) is for internally generating questions to stimulate needed conversations and for providing fact-based evidence to support decisions. Management accounting is for creating economic value. Financial accounting looks backward and reports. Management accounting is meant to understand the recent past and to look forward, just as every business must do to survive.

1. DO MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANTS KNOW WHAT THEIR INTERNAL CLIENTS WANT?

Perhaps CFOs don’t sufficiently understand the decision-making needs of the various departments they serve, such as marketing, sales, and operations. Today, with increasing global volatility, faster moves from competitors, and the Internet-led shift of power from suppliers to customers, a company’s internal users of management accounting information need a much sharper pencil than in the past. For example, users need to know the return on investment (ROI) for a marketing campaign or how profitable a customer is, not just a customer’s sales volume.

The decision maker is the management accountant’s client and deserves to be treated as such. That sharper pencil must address the issues related to the timing of information and the level of detail and accuracy in that information—critical factors in management’s ability to make good decisions.

A seasoned veteran (23 years of experience and who works for a company with $75 million in revenue) said: “[If] I have to discuss with my customers the right way to do their order, shouldn’t accounting treat me the same? If you wait until the month closes, you can’t do anything. I have to be proactive and get accounting to give me the numbers sooner. [They] do not understand the business, so there is a communication problem. We can’t assume they [the accountants] know [the business]. But they need to ask!”

The central problem here is that the CFO and the decision maker understand the rhythm of the business and the timing of decisions differently. In addition to their different frameworks, they don’t know who should reach out to whom: Should the accountants assume that there’s an undisputed way in which all businesses operate, or should they learn to adapt to the nuances of the specific business within which they work? These nuances revolve primarily around the level of detail, accuracy, and timing of data. Additionally, if accounting is a service that has internal clients, perhaps, as this veteran suggests, it should become more client focused, providing timely information and at the right level of detail and accuracy.

Another manager (27 years, $60 million in revenue) said, “I don’t like [our] accounting formats. [There’s] no consensus on what’s in the cost of goods sold. Nobody is sure what should go in there. Where’s all the rest of the value chain in that number? [I] hate the roll-up of all these cost allocations. I don’t know what goes into them and [so] I can’t manage them.”

That problem isn’t just about understanding how to treat managers like clients but also about helping both parties understand what the accounting information being provided means. This could be an issue of the manager being unaware of good accounting practices or of the accountant not educating the manager about what each piece of information being provided consists of and how it is constructed or calculated.

In today’s dynamic industries, where costs may not be well understood, this can be a source of tension and misunderstanding. Here are one manager’s opinions about cost allocations in the context of print and digital media: “This is why [our] media [division] is in trouble. They thought for some wacky reason that electronics [their digital content] just manufactured itself and we have no costs; it’s all free…and it isn’t. A lot of companies [in our industry] abandoned print too soon for digital and then found out it wasn’t so easy. You can’t charge the same amount for digital as you do for print!”

Was it the failure of the accountants to provide realistic information using an activity-based costing (ABC) approach with appropriate cost allocations that directly caused this bad decision, or did management fail to use all the data provided to them? Some people could argue that the manager should have challenged the accountant, but the manager already has a full plate. Managers rely on the accountants to reflect reality. At the end of the day, accountants need to recognize that they will take the blame.

2. DO MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANTS CARE ABOUT GIVING THE RIGHT INFORMATION TO INTERNAL CLIENTS?

Suggesting that management accountants don’t care is harsh, but sometimes it seems that they don’t care in an appropriate way. Their loyalty seems to be more to a disciplinary culture or to self-imposed codes of consistency, not to what the internal client wants and needs. One manager observed, “The paradox, which continues to puzzle me, is how chief financial officers and controllers can be aware that their management accounting data is flawed and misleading yet not take action to do anything about it…Now I’m not referring to the financial accounting data used for external reporting; that information passes strict audits. I’m referring to the management accounting [data] used internally for analysis and decisions. For this data, there is no governmental regulatory agency enforcing rules, so the CFO can apply any accounting practice he or she likes.”

The vast amounts of financial information that conform to disciplinary or self-imposed rules likely are meaningless to real decision makers. Management accounting information is meaningful only if it helps management make good decisions.

One manager (27 years, $60 million in revenue) complained that “[Accountants are too] rigid because they want to be consistent across divisions. But if divisions are different, you can’t give them all the same data because they have different data needs!” Another (30 years, $40 million in revenue) added: “They never make an exception even though every client is different, and they want to pigeonhole them.”

Who deserves the blame—or shame? Many accountants know they are misallocating cost calculations that violate costing’s causality principle. For example, they will allocate indirect expenses, commonly referred to as overhead, with cost allocation factors such as the number or amount of direct labor or machine hours, units produced, sales, or square feet. None of these factors reflects the consumption of the work activity costs. Activity cost drivers and their quantities for each activity more accurately reflect the costs.

This manager (42 years, $80 million in revenue) noted, “[Here’s a] process issue—if something is in the wrong account, Accounting just puts it somewhere else, and you don’t know where it went. But they don’t have the knowledge to know where it goes!” Added another (30 years, $40 million in revenue), “I need more details about the budget for my area. I need more detail about each of my major accounts. I know they have the information but choose not to share! I think part of this is that they are in the Dark Ages with respect to how much information can/should be shared.”

3. DO MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANTS HIDE INFORMATION?

Here’s a common failing: “One day the management accountant realized that the calculations and practices on which the cost system was based were incorrect. [They] did not reflect the economic realities of the company. The input expenses data was correct, but the calculated cost information was flawed. A broadly averaged cost allocation factor for indirect and shared expenses was used with no causal relationship to the outputs being costed. As a result, the current and forward-looking information provided to support the president’s decision making was incorrect. No one but the management accountant knew this problem existed. He decided not to inform the president.” Or perhaps the president does know that such problems exist but doesn’t communicate with the same language. Without a common language to express concerns, useful information wouldn’t be passed forward, so decisions would be based on partial information or on improperly aggregated information. Consequently, such decisions would become suboptimal and problematic.

Numerous complaints echoed those of this manager (42 years, $200 million in revenue): “There was no information sharing for months…and then you were still held responsible for profits. [There were] cost allocations you couldn’t control, and yet you had to explain [them].” Even rules of thumb can be hard to use if the information doesn’t arrive with the proper level of detail and accuracy and in time. Another manager (23 years, $75 million in revenue) noted, “I must have real-time data to make real-time decisions; you can always get lots of data, but it’s the timing and the accuracy [I need] because [then] you can make better decisions faster…I’ve got a budget that is a percentage of sales…if I don’t know sales, I don’t know what I can spend.”

Weaknesses in management accounting are real. The complaints we share here didn’t come from rookie managers (average tenure in the industry reported by the respondents was well above 20 years) in small and fledgling companies (average revenue of those reported was well above $50 million). The answers to the questions raised by the complaints from managers are simple to suggest. The solution to a lack of knowledge is more knowledge. Management accountants should spend time with their internal customers, explaining the numbers and procedures and answering any questions! The solution to the concerns about lack of caring is to realize that the management accounting information is critical to managing and improving the business. Just as a car with a great engine can sputter if it’s run on poor fuel, a great company will stall if it’s run on poor information—poor in timeliness and quality.

The solution to sweeping good information under the rug is to offer information that some can drill-down into. This is simple to do today with query software, and it can be made visible with nimble information systems such as ABC modeling tools. Numbers don’t exist on paper anymore, and they aren’t carved in stone. And each bit of information can have drill-down and roll-up capabilities, creating a truly live or reactive document.

This veers into the realm of information design, which is increasingly becoming an important responsibility of management accounting. In short, management accountants should not only generate timely, detailed, and accurate information, but they should also render it usable and valuable to the decision maker. Unfortunately, college curricula and corporate training focus on the former and not enough on the latter, so new and seasoned management accountants need the right skills and training.

Most colleges prepare their accounting students for jobs with auditing firms. Hence, the emphasis is on financial accounting. This is shortsighted because few accountants succeed in becoming partners in their firm and typically join organizations as financial managers where they need more management accounting skills.

4. ARE MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANTS CREATORS OF THEIR DYSFUNCTION?

Given that the dysfunction in management accounting is real, one natural question is whether management accountants are to blame. A management consultant commented, “Why do so many accountants behave so irresponsibly? The list of answers is long. Some believe the costing accuracy error is not that big. Some think that extra administrative effort required to collect and calculate the new information will not offset the benefits of better decision making. Whatever reasons are cited, accountants’ resistance to change is based less on ignorance and more on the accountants’ misconceptions about what determines and influences accurate costing.” The consultant understood that accountants wrongly perceive that employee time sheets are the primary source of cost accuracy. They are not. Cost accuracy is determined by properly modeling activity costs with their drivers.

Part of the problem is also the paternalistic attitudes some management accountants have toward their internal customers, treating them as unable to use or understand the numbers. But that isn’t a constructive attitude or conducive to good organizational functioning. Many times, the users of the numbers may understand the numbers as well as the accountants and because of their “skin in the game” may care differently about the trade-offs between timeliness and correctness. Said one manager (42 years, now in a company with $200 million in revenue): “I need real-time accurate profitability numbers on a daily basis…I can’t wait because then I can’t fix anything. I have done this a long time, [I’ve] built a number of companies…and you are only profitable if you know today how you did…otherwise, you can’t respond [in a way to become profitable].”

Another manager (32 years, $4 million in revenue) felt that the company’s management accountant was too much about the numbers and not enough about the business: “[Our CFO] didn’t really understand the business. In other places [where I’d worked before], the controller was like the [CEO’s] third arm, his savant, his advisor….The guy here is only about numbers [and not about advice].”

One manager actually defended the accountants: “I find that CFOs can have good insight into the business but are so busy doing [somewhat irrelevant] reports they don’t have the time.”

5. ARE THE METHODS WRONG?

Despite repeated calls from so many luminaries in the field, such as Robert S. Kaplan, and despite the clear value of providing more accurate costing, it’s apparent that organizations not using activity-based costing (or weak designs of it) when the conditions for ABC apply are providing inaccurate and misleading information to their users who are performing analyses and making decisions based on that flawed information. If decision makers don’t trust the information or don’t get the right amount of detail in the information with the right level of accuracy at the right time, they probably won’t use the information. Or, even worse, the decision makers will use the information implicitly, trusting it to be accurate, and will make decisions that are correct in terms of the information provided but wrong in terms of the outcomes generated. As examples, they might promote sales volume on a product or service that in reality is unprofitable or discontinue a product, thinking it is unprofitable when in fact it is very profitable. If this continues, the accounting profession as a whole loses credibility.

Here are three examples of data not having the right detail, right accuracy, and/or right timeliness:

Manager 1 (24 years, $11 million in revenue): “I need a report that would show profitability by profit center, and I need a report that would allow me to plug in different scenarios for staffing and pricing to see what the optimum would be. The reports I get right now are so integrated that…I can’t get the total picture. I am getting a bottom line, but it isn’t granular enough to show costs against each of the elements.”

Same manager: “The digital side of business [isn’t] fully loaded. We overload print products so digital looks good. The real expenses need to be charged…because digital looks better than it really is. I’m not a fan of allocations, but this needs to have some kind of [rationale to the] allocations because everyone is running around talking about how profitable digital is, but we don’t have the true expenses factored in!”

Manager 2 (10 years, $4 million in revenue): “Most difficult for me is the department allocations…why am I getting the allocations I am? I want the detail. I am ultimately responsible for the bottom line that includes those [costs]. I never get to see the full company data so I could see where I fit in. Am I pulling my weight? Do I need to pick it up?”

The annual budgeting process is also an issue. When many management accountants began their careers, creating reports for management meant giving programming requests to the data processing department, who, in turn, would say it would take 400 staff-days to write the code. Today, anyone with spreadsheet skills can create that same report in 20 minutes, and that includes many modern managers.

So what does management expect to receive from accountants for budgeting and planning? Many of those we interviewed are looking for something more than historical spending. They want trend data for their industry, for the industries of their suppliers, and for the industries of their customers. They want market intelligence. They want reliable forecasting tools.

One manager explained that he wants a report that would allow him to plug in different what-if scenarios for staffing and pricing to see what the optimum level would be for each “job” or customer.

Some decision makers felt that their accountants listened only during the budget cycle, then just forgot about looking ahead after that, instead focusing on reporting past results and variances the rest of the year rather than looking forward. An overriding theme from our interviews is that many of these managers just don’t care about using the budget as any kind of decision-making tool. They view it as a spending control tool. Others want to create their budget numbers almost as a game for obtaining rewards, so they rarely use them to manage the business. Examples of the decisions they make are whether to run a specific product on a specific machine, whether to buy more raw materials or not, whether to rework, or whether to run overtime shifts. None of this involves budgets. It’s about real-time, right-now forecasts of immediate needs, not what someone might do six months from now. A note to the progressive accountants: There should be a shift to top-down driver-based modeling using consumption rates with forecasts to calculate the required level of headcount and spending. This is a superior approach to bottom-up consolidations of cost center spreadsheets.

6. DO EMPHASES IN THE DISCIPLINE NEED TO CHANGE?

Managers increasingly should be shifting from reacting to after-the-fact reported outcomes to anticipating the future with predictive analysis and proactively making adjustments with better decisions. To close the gap, accountants should change their mind-set from management accounting to management economics. They need to classify resource-expense behavior with changes in demand and the planning horizon as sunk, fixed, step-fixed, or variable. This involves incremental and marginal expense analysis. Their reporting should be more customer-centric, going beyond just product costing to include order type, channel, and customer service expenses. To go from being reactive to proactive, the management accountant will need to communicate with all internal customers (such as sales and manufacturing) to adequately understand what the company’s customers want and how they behave. Management accountants can’t become proactive by stumbling around in the dark with their eyes closed. They have to open their eyes, focus clearly on the customer, and become familiar with what the customer needs and wants.

It also seems as if management accountants spend more time saying “no” than anything else. While there are legitimate areas where a “no” is required, the manager who has a reasonable request for information shouldn’t be denied just because “that isn’t how we do things here.” A company’s customers don’t care about internal issues and are even insulted when they’re told about a supplier’s internal troubles—they have businesses to run and don’t have time to be a confidant or friend to their supplier.

One manager (42 years, $80 million in revenue) noted: “[Their] tone is disrespectful against managers. Rules are made up as they go. We have had financial challenges, but management could have contributed to solutions if we weren’t viewed as the problem [by accountants].” And another (27 years, $60 million in revenue) remarked, “They are too firm on the rules…they have their ways and won’t change…and I will ask the same question(s) every month.”

In what other area can a client ask for something over and over again and not get it? Nevertheless, there’s some acknowledgment of the need for correctness, as in this quote from a decision maker (32 years, $4 million in revenue): “What works in this relationship? [They’re] accurate! Even about two-cent items. [He] was a pain in the neck, but I appreciated it. And he kept us in line and out of jail.” This balanced the view of another manager (32 years, $20 million in revenue): “[Our] prior controller was a ‘know-it-all’ who knew nothing! Did not know business and tried to make decisions about what data to share or collect. Was let go!” And someone else (27 years, $5 million in revenue) offered: “In one breath [they] tell me I am responsible, and then in the next I’m not. Plus, I don’t get the control [of data or decisions]. Allocations are [of] Titanic [impact] if business conditions go south.”

MAKING THE RIGHT CHANGES

Finance and accounting professionals won’t evolve from “bean counters to bean growers” if traditional practices continue. There are problems of willful blindness, wrong methods, and interpersonal styles.

Where are management accountants going? Perhaps they are running to business analytics, and much of the content of analytics is legitimately within the domain of management accounting. While Big Data and business analytics are becoming the playground for marketing and operations professionals, if management accountants don’t learn to apply advanced analytics, they could become increasingly irrelevant.

The widening gap between what management accountants provide and report and what decision makers need involves the shift from analyzing descriptive historical information to analyzing predictive information, such as budgets, driver-based rolling forecasts, cost estimates, and what-if planning scenarios. Yet everyone can learn and gain much from historical information. Although accountants are gradually improving the quality of reported history, decision makers are shifting their view toward understanding the future better. This shift is a response to a more overarching change in executive management styles—from a command-and-control emphasis that is reactive (such as scrutinizing cost-variance analysis of actual vs. planned outcomes) to an anticipatory, proactive style where organizational changes and adjustments, such as staffing and spending levels, can be made before negative things happen and before minor problems become big ones.

October 2015