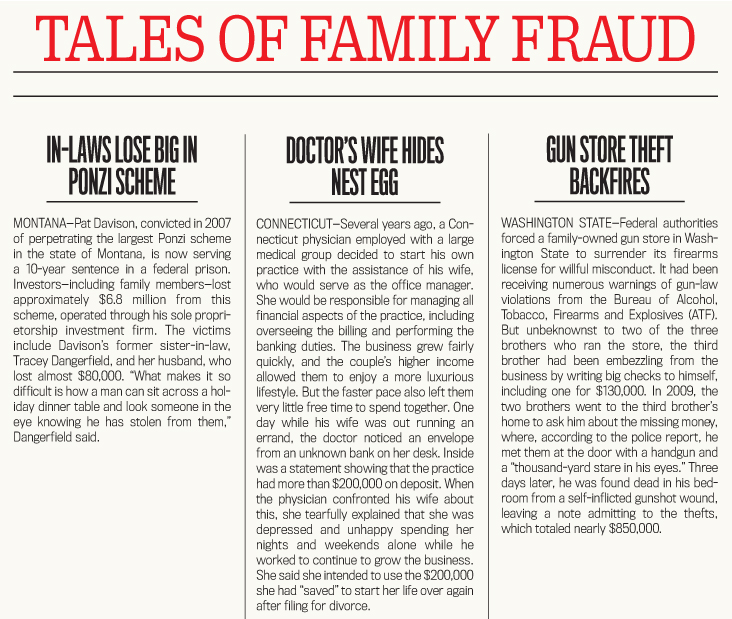

The three real-world tales demonstrate clearly that fraud can be committed against family members by an in-law, sibling, or spouse—no family relationship is immune. What makes fraud worse in a family business is that the relationships can be changed forever once a relative has perpetrated fraud, and this may often include the dynamics between family members not involved in the fraud itself. Understandably, emotions can run very high. The psychological trauma is impossible to quantify: In addition to experiencing a number of disturbing feelings, the honest family members may not have the ability to trust anyone for some time. Feelings of denial, followed by anger, are typical.

For the purposes of this discussion, we’re defining a “family business” as any organization in which one or more family members established or currently operate the entity (or both), with at least one family member at the owner level. Often, one generation (grandparents or parents, for instance) started the business, and it became a “family” business when subsequent generations joined the company. But family businesses aren’t limited to lineal succession. Siblings establish many family businesses together, and aunts, uncles, cousins, and in-laws may be part of those businesses or others.

THE MAGNITUDE OF THE PROBLEM

It’s hard to find reliable statistics about fraud perpetrated by people against their own family. At best, the numbers are estimates because not all cases are discovered, and those that are often go unreported. Further, when a trusted family member is the perpetrator, other relatives often pressure the victims to “keep peace in the family” and resolve the matter quietly.

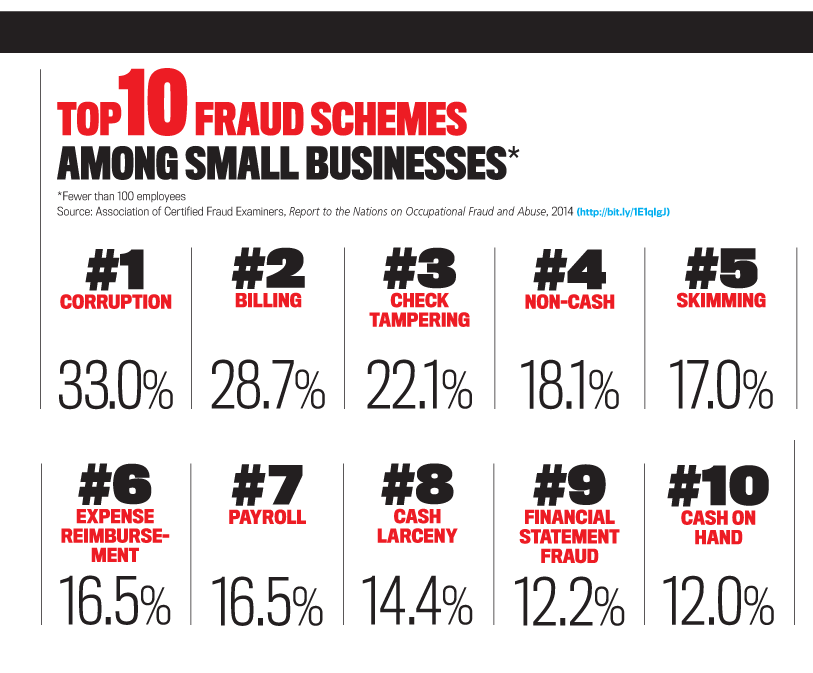

You can gain some appreciation of the magnitude of the problem of fraud within family businesses from the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) in its 2014 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse (http://bit.ly/1E1qIgJ). More than 34,600 Certified Fraud Examiners (CFEs) were asked 84 questions about the single largest fraud case they had investigated between January 2012 and December 2013, with the criteria that the investigation must have been completed and the investigator was reasonably sure the perpetrator had been identified. Responses representing 1,483 fraud cases meeting these criteria were compiled.

While the report doesn’t provide specific results about fraud perpetrated by family members, family businesses account for a large percentage of small organizations, and the report does contain findings about them. The ACFE defines a small business as one with fewer than 100 employees, and it’s this group of businesses that’s consistently reported as being victimized in the greatest percentage of cases.

As you can imagine, many types of family businesses fall into the ACFE’s “small business” definition, such as restaurants, hardware stores, landscaping and tree services, automotive repair shops, construction companies, grocery stores, motels, clothing stores, funeral homes, and manufacturing companies, to name just a few.

Further, the ACFE consistently finds that the median fraud losses for small businesses are the highest or close to the highest among all business sizes. (Median losses are reported rather than average losses since an average can be significantly skewed by a few very high-dollar frauds; consequently, the ACFE believes median losses provide a more accurate and conservative picture of the typical impact of fraud.) The 2014 survey found that organizations with 10,000 or more employees had the highest median fraud loss per incident, at $160,000. Remarkably, though, small businesses had the second-highest loss, at $154,000—a mere $6,000 less than the group that includes some of the world’s biggest companies. It probably goes without saying, however, that the impact of the $154,000 median loss for a small business will be felt much greater than the relative impact of a $160,000 loss at a much larger organization.

Beginning in 2010, the ACFE gathered its data from fraud cases throughout the world rather than solely in the United States. The 2010 global fraud survey included offenses that occurred in approximately 100 countries on six continents, with more than 43% of the cases taking place outside the U.S.; the 2012 and 2014 global surveys report a similar composition of data. Also, from 2002 through 2014, the ACFE consistently found that small businesses always suffer a higher frequency of fraud than businesses of other sizes.

IT WON’T HAPPEN TO US—WE’RE FAMILY!

If only this were true. Fraud surveys repeatedly find that no company is immune to deception and outright theft, regardless of geographical boundaries, industry, size, or form of ownership. In short, any business is potentially vulnerable to fraud. A company that takes the approach that blind trust is an internal control—simply because of family status—is even more vulnerable by ignoring potential risks and not taking the necessary precautions to protect the business. Compounding the problem, employees who aren’t family may be inadvertently afforded the same level of trust given to family members.

Further, it’s a fallacy to believe that a compensating control for blind trust is an innate instinct to know if a fraud is occurring (“Oh, I would know if someone were ripping me off!”). Fraud surveys from the ACFE and other groups consistently find that fraud is most commonly detected through tips, regardless of the source (vendors, employees, customers, or an anonymous source). Sometimes family members knew, or at least felt, that something wasn’t right with their relative’s behavior or actions, but, because of the family relationship, no one acted soon enough to limit the exposure to loss.

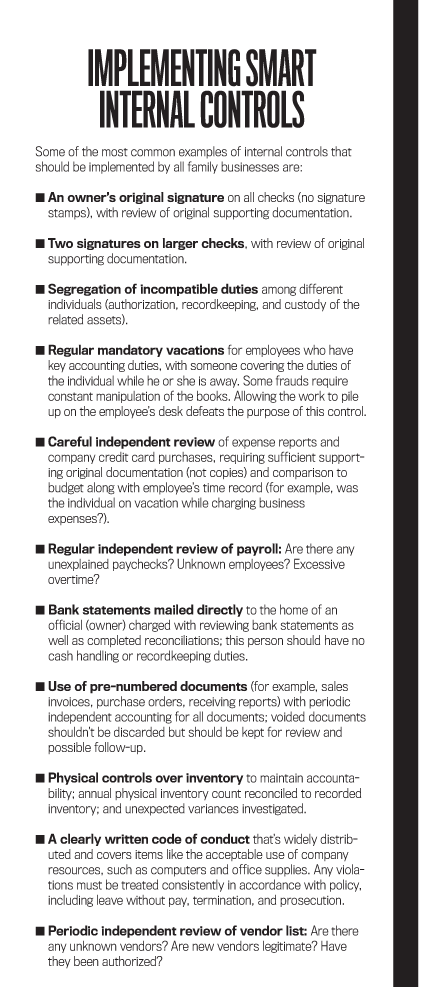

Examples of typical frauds perpetrated in family businesses are shown in the sidebar “Common Fraud Schemes in Family Businesses.” Important internal controls that should be implemented to prevent these sorts of crimes are shown in the sidebar “Implementing Smart Internal Controls.”

A SENSE OF ENTITLEMENT

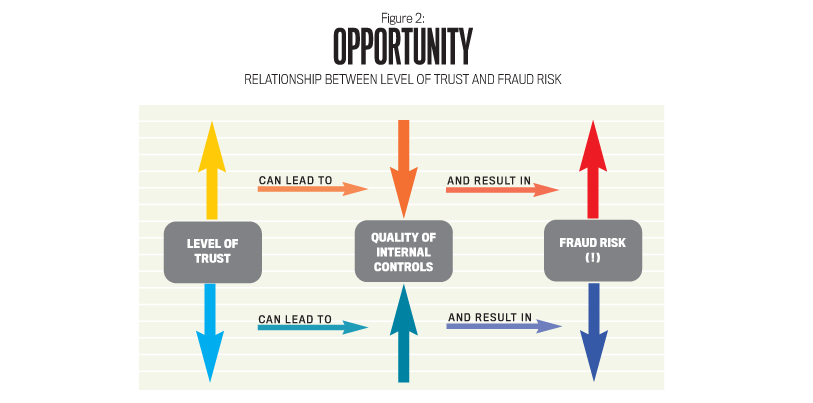

How is fraud possible in a family business? For any entity, large or small, the most widely accepted theory researchers have developed to explain why fraud occurs is the “fraud triangle.” Within this triangle, three elements—pressure, opportunity, and rationalization—are necessary for fraud to occur (see Figure 1).

Examples of the pressure or motive to commit fraud may be a financial need to support a lifestyle that the person’s legitimate salary can’t sustain or to support an addiction problem. The second element—a perceived opportunity to be able to commit the fraud and remain undetected—typically will manifest itself in poor or missing internal controls. Again, blind trust is not an internal control. Believing family members are the most trusted people of all is actually a weakness and results in less oversight, if any at all. As shown in Figure 2, this creates a perfect environment for fraud to flourish.

The third element, rationalization, requires that the perpetrator somehow justify in his or her mind why the fraud scheme isn’t a criminal act. Given the sense of entitlement prevalent in our society today, it might not be a surprise that the “Big E” (for “entitlement,” not “ego,” although perhaps that’s related) is a common rationalization in family businesses: “I’ve worked harder than any of my brothers and sisters in this business, so I’m doing nothing wrong by taking this. In fact, I deserve this.” At the same time, second and third generations might not be aware of the financial struggles and sacrifices that the first generation made to establish the business, which reinforces a false sense of entitlement.

AN OUNCE OF PREVENTION

Given the elements of the fraud triangle, the best preventative approach is to increase the perception of detection, which can be achieved through proper internal controls. But the possible caveat with a family business is that family members may believe any fraud they commit won’t be reported or prosecuted for the sake of “keeping peace in the family.” Consequently, it’s important that internal controls be properly designed, implemented, and updated as necessary, including a written policy of how fraud will be handled immediately.

Implementing proper internal controls in a family business may be a sensitive issue. Every family business is as unique as every family, and family dynamics can vary. Thus it’s critically important that the dominant family member is on board with and supportive of having a fraud risk assessment performed and the recommended internal controls implemented. (We’ll talk more about this later.)

The topic can be presented properly to family members by explaining that good controls equal good business. Implementing proper internal controls protects all employees, the family, the company’s reputation, and, of course, the bottom line. Without adequate controls, the risk of fraud increases and, with it, damages beyond monetary loss. For instance, the damage to the company’s reputation could affect future sales. Employees may find fraud to be demoralizing, which can result in decreased productivity and increased turnover. Legal costs will be incurred if the company chooses to prosecute. And if the fraud is significant enough to affect the company’s solvency, this certainly affects future heirs as well.

Trustworthy individuals won’t have a problem with controls being in place. Adequate controls can actually help build trust, which will allow all employees to feel more confident that the records are accurate and the potential for fraud has been minimized.

Since many family businesses are relatively small, the lack of resources to establish and maintain a solid system of internal controls will usually be a concern. But this problem can be solved by including compensating controls. For example, if certain accounting duties can’t be segregated adequately because the business has an extremely small accounting department (perhaps consisting of one “trusted” individual), internal control can be greatly enhanced by having the bank statements mailed directly to the owner’s home. The one-person accounting department can still have the authority to write checks in addition to incurring the expenses and recording the payments—as long as the owner signs all the checks and receives and reviews the monthly bank statements. These simple steps can increase the perception of detection, which will greatly enhance the prevention of fraud.

METING OUT PUNISHMENT

What happens if fraud is discovered in a family business? Many times the family doesn’t want someone arrested, fearing it will be ripped apart (which just about always happens, regardless). Uninvolved family members may advocate for peace within the family and pressure the victimized members to let it go, all of which can complicate family relationships. If a problem exists, say, between two siblings running a business, often the parents and the children of each sibling get involved, all offering their advice and opinions on what should be done to resolve the issue. Misinformation from one family member spreads like wildfire to other, previously disinterested family members, and before long nearly the entire family is consumed with an issue that has nothing to do with 99% of them!

But sometimes the family is willing to pursue prosecution, which will come with its own set of problems. The general view of law enforcement and the court system pertaining to fraud involving family is that there’s too much other “real” crime to deal with beyond a family spat. Moreover, fraud cases can be complicated and hard to understand, especially for those without an accounting background, which causes further reluctance on the part of the legal system to get involved. In addition, intent must be proven with a fraud case, which can sometimes be difficult unless there’s been a pattern of attempts to try to conceal the fraud. Finally, it’s very common for the defendant’s attorneys to implement the tactic of “delay, delay, delay!” This approach drags out the process, which increases legal fees along with stress in the family and resolves nothing.

Occasionally, victims can recover embezzled funds through insurance, assuming such coverage existed prior to the fraud and doesn’t exclude fraudulent acts by business owners or family members. The catch is that many policies today include a provision that the victim must contact law enforcement if he or she suspects potential criminal violations. Consequently, if the family decides not to press charges, this may prevent any recovery through insurance.

If civil, criminal, and insurance recovery options aren’t pursued for any reason, victims have little remaining recourse. Sometimes the dishonest family member will promise to repay the stolen amount, but if he or she didn’t need the money so badly in the first place, the embezzlement probably would never have occurred! So the chances of the victim recovering the lost funds in this manner are practically nil.

A CAUTIONARY TALE

Does all this sound improbable? Consider the following true case (identifying names and places have been changed).

John created Custom Cabinets from the ground up. A skilled carpenter specializing in fine woodworking, he managed to grow the business to the point where Custom Cabinets became the sought-after name in kitchen and bathroom cabinets. As the demand grew, so did the orders, and John often found himself split between the sales, production, and administrative duties, which resulted in long days and no weekends off.

To allow for further expansion and decrease his stress, John asked his two brothers, Mark and Kevin, to join the company. Mark took over the administrative functions, including billing, collections, disbursements, and payroll, while Kevin assumed the marketing role. Since Mark and Kevin were family and agreed to grow John’s company, John modified his business’s ownership structure, giving one-third of his company to each brother while retaining one-third.

As orders increased, John found himself hiring more production staff in order to meet demand. Spending long days and weekends running the shop, John relied on Mark to ensure the finances of the company stayed healthy. Mark claimed the administrative functions were beyond one person’s capabilities, so he brought in his wife, Tammy, to assist him.

Unfortunately, the cash flows didn’t follow the growth, and vendors started shutting off Custom Cabinets from future orders. John couldn’t understand what was happening since he had had a great track record of paying his suppliers, and there should have been plenty of cash available to meet the company’s purchase obligations. Logically, John went to Mark and Tammy to determine what was happening with the finances. He was told things would be fine and that he should return to the shop and allow them to respond to the suppliers.

John didn’t pursue the issue, which proved to be his fourth major mistake, preceded by (1) bringing his brothers into his company, (2) giving them ownership interests, and (3) allowing Mark to hire his wife as an employee.

After a short period of time and more delays in deliveries of much-needed materials, John demanded answers from Mark as well as access to the financial records. What John received instead was a termination of employment! Mark even went so far as to change the locks on the buildings, preventing John’s access. In the meantime, Kevin sat quietly in the background, not choosing one side over the other. For this perceived “loyalty” to them, Mark and Tammy gave Kevin bonuses (payoffs, if you will).

John and Mark each retained attorneys, and a long legal battle began. Two years and thousands of dollars later, John received his first glimpse into partial records of his company. Mark and Tammy had used the corporate funds as their personal checking account, racking up personal expenses on more than 40 different credit cards paid through the company. Further, Mark and Tammy started a separate business of their own and used the company’s funds to buy materials for it.

John wanted Mark and Tammy arrested, but law enforcement wasn’t interested in resolving a family dispute. Instead, he filed suit against his brother and sister-in-law for stealing the funds as well as his company. Two years of hearings resulted in large legal bills but no resolution. John then sought to recover the stolen funds through an insurance claim (he was still a one-third owner), but the policy excluded claims where an owner was the perpetrator.

Sadly, John ended up settling the case against Mark and Tammy for a mere $90,000, paid over time, which represented a fraction of the company’s worth. Mark, Tammy, and Kevin continued to own and operate the business that John had started, and John found himself starting over, alone. His wife had left him during the long, drawn-out, stressful process.

STOPPING FRAUD BEFORE IT HAPPENS

Creating opportunities for family members to work within a family-owned business can provide benefits that include stable employment and wise succession planning in addition to some wonderful nonmonetary perks, such as bringing relatives closer together.

But even in the best-run family-owned businesses, the potential for embezzlement or other fraud is never far away. Situations change, tempting some people to break the law, or owners grow complacent as the years pass, placing too much trust in certain family members. For these reasons, families should consider investing in their business by having a CMA® (Certified Management Accountant), a CPA (Certified Public Accountant), or a CFE—or, even better, a combination of the three—conduct a fraud risk assessment to identify missing internal controls. Implementing proper controls, rather than relying on the blind trust of family members, can increase the perception of detection and minimize the perceived-opportunity element of the fraud triangle, thus greatly reducing the risk of fraud.

Something else that could pay dividends is having as part of the internal control environment a written code of conduct that includes anticipating the possibility of having to remove a family member from the business. The code of conduct needs to be circulated widely, enforced consistently, and include evidence that each employee/family member has read it, which will be invaluable if a dispute with a family member ever develops. In the long run, no matter what Auntie Annie, Brother Bobby, or Sister Susie says, that likely will be the best way to keep peace within the family.

May 2015