To analyze future risks and opportunities in a global environment, business leaders not only must understand the risks of operating within their own markets but also how their business will be affected by complex international political, economic, and regulatory issues, as well as by potential disruptions in supply.

A GLOBAL CONCERN

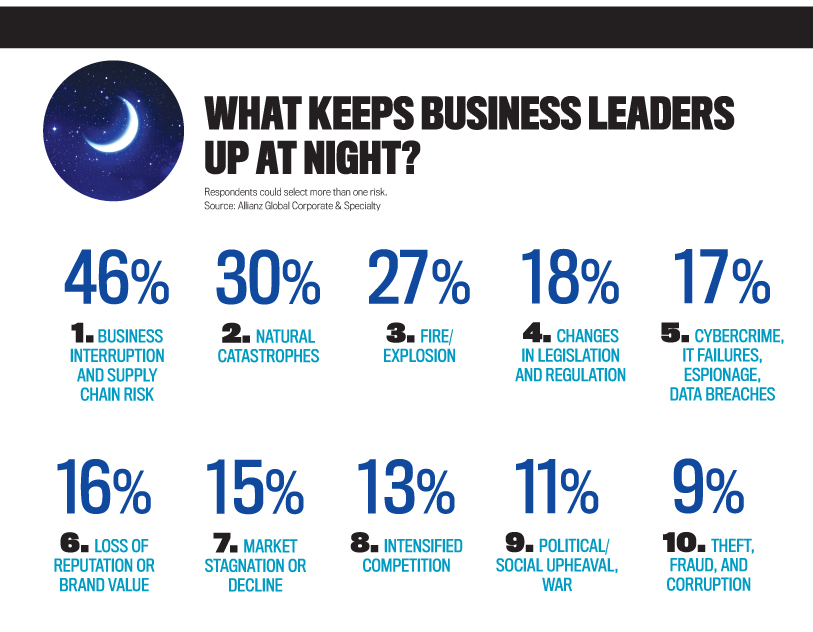

In its recent survey of 516 business and risk consultants, underwriters, senior managers, and claims experts in 47 countries, Allianz SE, a multinational financial services company headquartered in Munich, Germany, identified the major business concerns for 2015 and the coming year that are likely to impact all companies. Which risk ranked the highest? According to the survey, it was an interruption to the business and supply chain. This was followed by natural catastrophes, a fire or explosion, changes in legislation and regulation, and, rounding out the top five, the category of cybercrime, IT failures, espionage, and data breaches. (For a detailed view and analysis of the top 10 risks by region, see “Allianz Risk Barometer: Top Business Risks 2015” at http://bit.ly/1y1ntVE.)

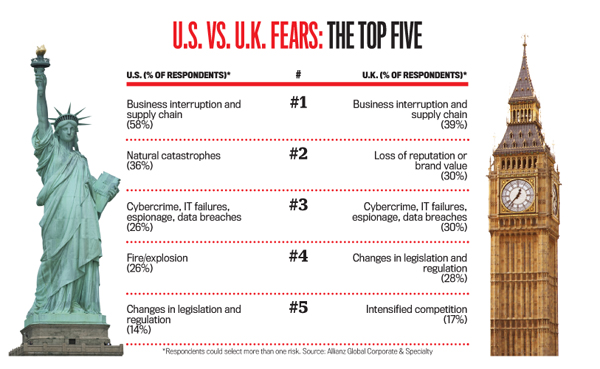

Executives from the United States and the United Kingdom rated business interruption and supply chain risks as the most important risks for the coming year. But U.S. companies ranked natural disasters as their second-biggest risk, while U.K. executives ranked the loss of business reputation or brand value (such as from attacks on social media) as their second-most important fear. U.S. companies are far less concerned about loss of reputation or brand value, ranking it sixth in their top 10 concerns.

Thomas K. Varney, a Chicago-based regional risk consulting manager for Allianz, points to diversity in production and the popularity of Just-in-Time (JIT) manufacturing as two critical factors underlying the reason for growing concerns over supply chain risk. “Parts can be manufactured off-site in one region and assembled in another, so any disruption in one region can create a very tangled web of impacts,” he says.

From a business interruption standpoint, because you’re also vulnerable to your suppliers’ suppliers, what you consider a small supplier could actually create a significant impact, Varney adds. This is where the risk manager needs to have as much data as possible across the organization’s entire supply chain. Furthermore, he notes, because suppliers come and go routinely, a company’s risk exposure can change almost daily.

THE VOLATILITY OF RISK

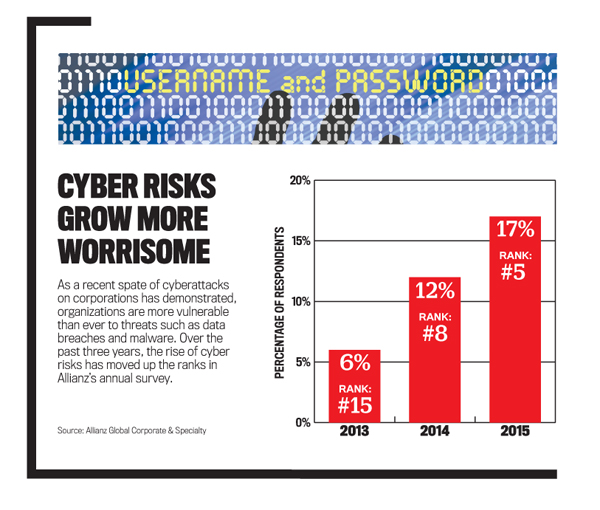

The Allianz survey revealed that concerns around business risks also varied according to market maturity, with executives from emerging economies and more volatile political regions showing greater anxiety regarding natural disasters and market stagnation than those in developed economies. It also demonstrated that country risk profiles change from year to year, making risk assessment more difficult as companies become more exposed. For example, risks associated with political/social upheaval and cybercrime are of greater concern in 2015 than they were in 2014, whereas companies (although still pointing to a high level of risk) are less worried about the impact of disruptive technological change or the effect austerity programs are having on local economies.

Perhaps not surprisingly, size also matters when it comes to risk.“The large company probably has economies of scale that a smaller company might not have,” Varney explains, adding that a larger company likely would have its own risk management structure whereas a smaller company may have just one person assigned to monitor risk, possibly among his or her other duties. “Also,” he says, “when we’re talking about contracts with suppliers and the ability to possibly stockpile critical parts or critical pieces that may be needed, larger companies might be in a better position to mitigate disruption risks or develop an internal business continuity plan.”

RISK REGULATION AND CONTROL

As the global risk environment changes, local and international regulatory and standards-setting bodies are responding in a variety of ways. Take the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), for example. In 2013, the U.S.-based risk management think tank and issuer of risk management and internal control guidance released its revised Internal Control—Integrated Framework to reflect the changes in the operating and risk environments that have occurred over the past 20 years. More specifically, COSO pledged to make the “existing Framework and related evaluation tools more relevant in the increasingly complex business environment so that organizations worldwide can better design, implement, and assess internal control.” Then in fall 2014, COSO announced updates to its 2004 Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework, which are being developed by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) under the direction of the COSO Board. (For more information, visit www.coso.org.)

At the same time, the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) required U.S. banks and credit unions to step up their third-party risk assessment/due diligence processes. The new guidance covering third-party relationships, OCC Bulletin 2013-29, “Third-Party Relationships: Risk Management Guidance,” recognized changes in the global risk environment, pointing to increased operational, compliance, reputational, strategic, and credit risks associated with entering into business relationships with outside vendors, particularly as they relate to information security. (See http://1.usa.gov/1JkXJol.)

In addition, more recent comments before the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs foreshadow regulatory changes to come for telecom, energy, and retailers. As Valerie Abend, senior critical infrastructure officer for the OCC, noted in her comments, “The OCC strongly supports efforts to ensure other sectors have commensurate standards and improved transparency as it relates to the cybersecurity preparedness for these other sectors.”

The financial services industry and retailers have “interdependencies,” she added, which need to be accounted for—in good times and bad. “We have seen a number of attacks on large retailers in which credit card and other information from millions of consumers was compromised. In response, financial institutions compensate customers for fraudulent charges, replace credit and debit cards, and monitor account activity for fraud at significant cost. We would support efforts to even the playing field between banks and merchants to ensure that both contribute to efforts to make affected consumers whole.”

Overseas, changes in the global risk profile have been recognized by local regulators such as the U.K.’s Financial Reporting Council (FRC), which issued an updated version of the U.K. Corporate Governance Code in September 2014. The FRC says that this new version “significantly enhances the quality of information investors receive about the long-term health and strategy of listed companies, and raises the bar for risk management.”

A DANGEROUS CONTAGION

The interdependencies between markets and the known contagion in the financial system have made it clearer than ever that business risks aren’t confined within geographic or political borders. How the financial system is closely interconnected between countries is demonstrated by the way the U.S. financial crises affected banks and insurance companies in Europe and other international holders of toxic assets.

Experts from the U.K.-based Institute of Risk Management (IRM), for example, point to the impact of falling oil and gas prices on political and social disruption in oil-producing countries, “which, if not successfully managed, will impact on the world,” says Mark Boult, fellow of the IRM. For Canada, an oil-dependent economy, The Conference Board of Canada estimates that, in Alberta alone, total business investment could be cut by C$12 billion in 2015, leading to a potential recession in that province. The Conference Board also expects total pretax profits from all Canadian corporations to drop by C$25 billion, from record 2014 levels of C$275 billion, as a derivative effect.

What about the impact of global energy prices on the U.S. economy? For PwC Advisory Director Mitzi Campbell, this is still a moving target. “The fallout of the crash in the price of global oil could potentially put off many development projects here at home,” she says. “If I were the CEO or CFO of a company, I would be preparing for the potential for even higher than normal fuel prices a year down the road and the [associated] impacts on my cost structure and pricing models.”

Stuart Buglass, a vice president at Radius, an international growth and expansion consultancy based in the U.K., identifies how international regulation can also have a profound impact on the risk management strategies for U.S. companies. For example, one issue for his clients, he says, is where U.S. parent companies have operations in the U.K. and both countries have strict corruption and bribery legislation—the Federal Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in the U.S. and the Bribery Act in the U.K.

“What you find,” Buglass explains, “is that the reach of those pieces of legislation is so great that if you’ve got activities being performed by any group company, by any employee of a subsidiary, or even a third party connected to your parent company, you could fall afoul of the FCPA or the Bribery Act, even though those activities aren’t really being controlled by the parent company. Most of our U.S. clients, even if they operate with a small footprint in the U.K., will have the U.K. legislation applying to them as well. So they’ve got to be aware that they shouldn’t just have all of their internal policies and controls focused on the FCPA. They need to consider the Bribery Act as well.”

Because of these increased risks from third parties, your organization needs to have tighter controls within the countries where those third parties are based, Buglass says. “You could be on the hook for the actions of, for example, local design companies or engineering companies or accountancy firms if they’re seen as being corrupt,” he notes. “It comes down to having that local control and being really confident in the abilities of your local country manager.”

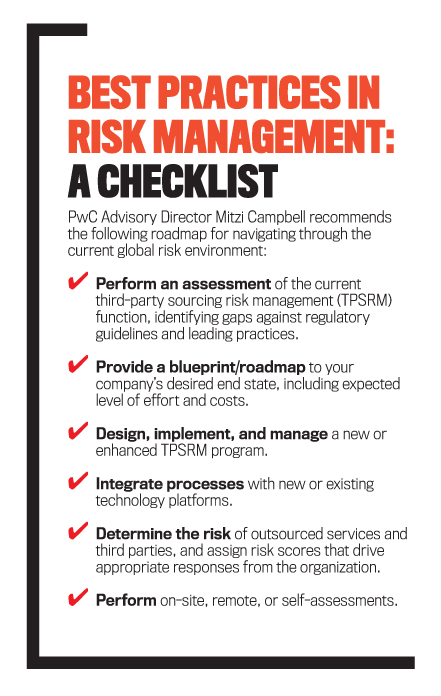

Mitzi Campbell agrees, adding: “In this rapidly changing world of risk, we recommend a quarterly scorecard approach that evaluates key supplier risks on a regular and ongoing basis.”

Also on the international political front, companies that have major interests in the European Union (EU), which is the U.S.’s largest trading partner, are encouraged to keep a close eye on the evolving dialogue between the U.K. and the EU. José Morago, IRM chairman and group risk director at Aviva, a British multinational insurance company, notes, “The potential risk of a U.K. exit from the EU could bring even bigger strategic, operational, and legal risk challenges to many international companies than those raised by Scottish independence.”

According to Mark Butterworth, IRM member and managing director at Condie Risk Consultancy, the 2014 U.K. Corporate Governance Code and the FRC’s guidance on risk management together will significantly upgrade the “weaponry of shareholder activism in 2015.” This, he says, will consequently require greater corporate governance and risk management education at the board level. “Boards need to identify governance gaps and plug them fast—whether that’s through acquiring new skills, qualifications, or experience. What is expected from boards is going to be raised quite fast next year.”

ARE COMPANIES MANAGING RISK SUCCESSFULLY?

As regulations and standards evolve to try to match the increased complexity of the global risk environment, the question remains: Can companies keep pace?

A February 2015 report by the ERM Initiative at North Carolina State University, in conjunction with the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), on the state of enterprise risk management, says “No.”

According to the survey, conducted in fall 2014, despite the fact that more than 59% of the 1,093 executives who responded thought that the volume and complexity of business risks had increased considerably in the past five years, only 23% of them described the level of their organization’s risk management as either “mature” or “robust.”

In addition, the survey reported weakness at the board level, where only 27% of executives indicated that their boards substantially discussed the top risk exposures facing the company in relation to its strategic plan.

Finally, and perhaps of greater concern, is that just under half (43%) of executives responding to the survey indicated that their companies had no structured process for identifying and reporting top risk exposures to the board. An additional 27% describe their risk management processes as informal and unstructured with ad hoc reporting of aggregate risk exposures to the board.

Not surprisingly, the authors call for organizations to strengthen their underlying processes for identifying and assessing key risks facing the entity and integrating risk oversight with strategic planning efforts. (View the full survey, “2015 Report on the Current State of Enterprise Risk Oversight: Update on Trends and Opportunities,” at http://bit.ly/1ybb0z2.)

Other recent studies also show that audit committees specifically are concerned about the evolving risk environment and their ability to oversee risk at the governance level. According to KPMG’s 2015 Global Audit Committee Survey (http://bit.ly/1Dgj8yn), the key concerns on their respondents’ radar in 2014 carried over into 2015, namely political uncertainty and volatility, regulatory compliance, and operational risk, which were identified as the greatest challenges for the coming year. What has changed is that the vast majority of the 1,500 audit committee members responding to the survey indicated that the time required to carry out their responsibilities increased compared to last year. At the same time, they’re doing more with less, with many acknowledging that, in addition to financial oversight, they hold at least some responsibility for significant aspects of risk oversight, such as cybersecurity and technology, global compliance, operations risks, or the company’s risk process in general.

If these threats seem overwhelming—especially to leaders of small companies—in many respects they are. Thankfully, however, many organizations, such as COSO, IRM, and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), which promulgated ISO 31000—Risk Management, also offer guidance around risk management for the enterprise as a whole to assist companies in navigating the constantly evolving global risk landscape.

May 2015