During this same decade, boards of directors and senior executives have faced a number of challenges related to their oversight of risks. In response, a number of them have embraced enterprise risk management (ERM) as a paradigm to help them focus on a top-down, holistic process of identifying those risks arising across the organization that are most likely to affect whether the enterprise achieves its objectives. As part of their ERM launch, executives have attempted to identify all types of potential risks that might be most impactful to the organization’s strategic success, and they’ve developed processes to prioritize those risks and have allocated resources to manage them.

Despite both of these emerging governance trends, few organizations have realized the benefits of integrating their sustainability efforts with their enterprise-wide risk management oversight. Leaders of the organization’s sustainability initiatives often are distinct and separate from those leaders who manage risk. Yet there are tremendous synergies and benefits to integrating an organization’s sustainability and ERM efforts into a single, coordinated process linked directly to the company’s core strategies.

WHAT CONSTITUTES SUSTAINABILITY?

To help make this connection, we like to think of sustainability as those issues that might impact the long-term viability of an enterprise. By looking at things this way, a strategic framework emerges that helps companies be less prone to focusing solely on narrower interpretations of sustainability factors—such as those linked just to declining natural resources, energy consumption, or waste reduction—and more apt to think broadly about all kinds of risks and opportunities that might impact their long-term business model and achievement of strategic objectives.

Organizations are working to enhance their risk and sustainability thinking to reshape business models and behaviors. Specifically, the CDP S&P 500 Climate Change Report 2013 notes that 87% of the 334 reporting companies “either have a dedicated climate change risk management process in place or have integrated climate change into their company-wide risk management processes.” The 2014 report features the investment implications of climate change management for the first time in the nine years CDP has been compiling the reports “to shine a light on the link between strong climate change management and measures of financial performance and, at the very least, to put to rest the common misconception that taking action on climate change exacts a cost to profitability.” Given these trends, we’ll outline an approach to link ERM with sustainability thinking.

WHERE SUSTAINABILITY AND ERM INTERSECT

There’s a tremendous argument for marrying an organization’s ERM and sustainability initiatives to address risks and opportunities that are most likely to impact the organization’s ability to sustain its strategies and its business model for creating long-term value.

An example from The Coca-Cola Company helps emphasize the importance of this point. In 2009, the company launched its 2020 Vision, which identified a number of points to help it achieve its goal of doubling its revenues to $60 billion by 2020. That goal triggered several critical sustainability questions for the company as to whether it would be capable of doubling the production and sale of its beverage products from the current level of 1.8 billion per day. For instance, will there be sufficient global access to water and other key ingredients to meet this projected demand?

To address these challenges, the company embarked on a significant sustainability effort in support of its 2020 Vision, which is centered on six “Ps”: People, Portfolio, Partners, Planet, Profit, and Productivity. Additionally, it focused its ERM efforts on understanding the critical risks in the company’s business strategy to ensure that its risk taking is purposeful and appropriate as it seeks to achieve the objectives set forth in its 2020 Vision. One result of this effort is that Coca-Cola reduced the water used to produce a liter of product from 2.7 liters in 2004 to 2.08 in 2013—a 23% improvement over nine years.

Coca-Cola’s approach helps illustrate the importance of integrating risk and sustainability thinking. Let’s take a closer look at how that might be done in your organization.

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE STRATEGY

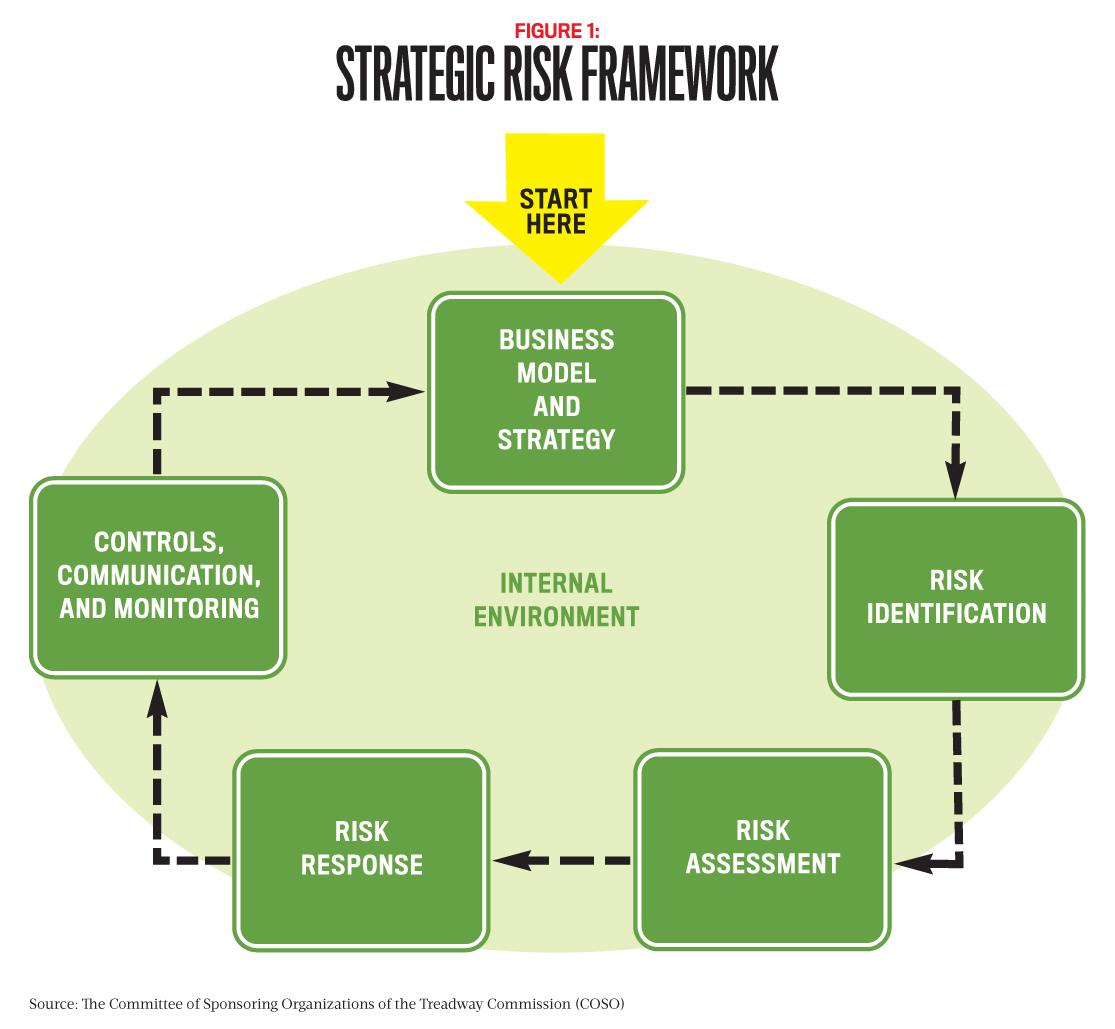

When working with executives in their efforts to implement ERM, we emphasize the critical importance of beginning any endeavor with a rich understanding of what drives the business’s success today and identifying strategies designed to protect the enterprise and create value in the future. The process we use is illustrated in Figure 1.

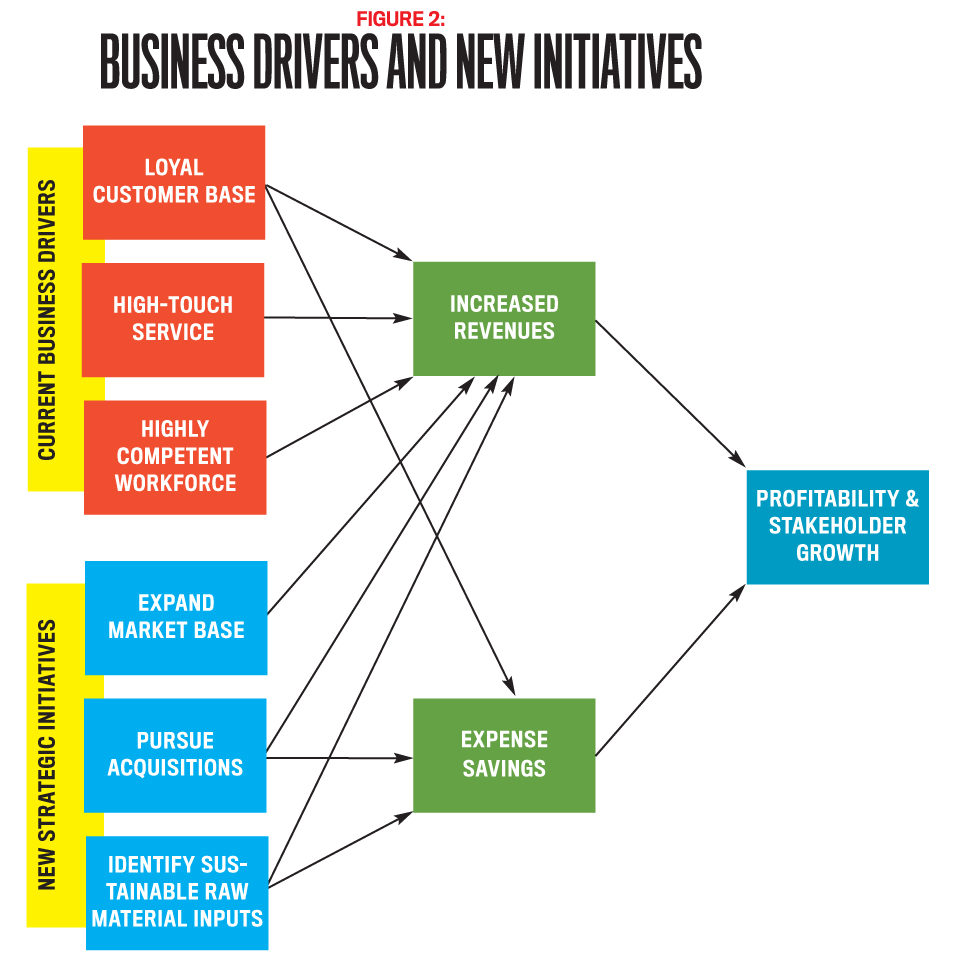

A strategy-focused ERM effort begins with management taking the time to clearly articulate the current key business drivers and planned new strategic initiatives that are being implemented to drive stakeholder value (see the top box in Figure 1). This starts with management developing a comprehensive “big picture” view of what makes the business tick so it can identify and assess risks using a strategic lens on those value drivers (think of these as the organization’s current “crown jewels”). They are illustrated in Figure 2 using a hypothetical example in the three red boxes labeled “Current Business Drivers.” In this example, the organization’s loyal customer base, the high-touch (more personalized) service it provides for those customers, and the highly competent workforce, among other factors not shown, are major drivers of success today.

The process also involves pinpointing specific new initiatives contained in the current strategic plan that management will be implementing to create value in the future as illustrated by the three blue boxes in Figure 2 labeled “New Strategic Initiatives.” In this example, the organization seeks to grow shareholder value by expanding its base into new markets, pursuing acquisitions, and identifying sustainable raw material inputs.

The goal of any ERM process is to identify those risks that are most likely to have the greatest impact on current business drivers and new strategic initiatives so that management can rank and prioritize them. This is where the sustainability lens is critical. By asking what might emerge that would impact the long-term viability (the sustainability) of a current core business driver or new strategic initiative, we now have a framework to use to think through the portfolio of sustainability challenges that might emerge. For some companies, a major risk to the business may be tied to declining natural resources or the lack of available energy needed to deliver a core business driver or new strategic initiative, while for others the challenge may be linked to shifts in social norms or population changes that lead to reduced (or increased) demand for their core products and services. Thus the focus on sustainability is less about the flavor-of-the-month topic and more about risks—any risks—that might impact the enterprise’s long-term business drivers and strategic initiatives.

By mapping risks to drivers of the business, management and boards can better understand why risk oversight from a sustainability perspective is important to the organization’s long-term strategic success. To complete a comprehensive risk and strategy assessment, management should think about each of the organization’s core business drivers and new strategic initiatives along two primary themes:

- What must go right for us to advance the success of our core business drivers and new strategic initiatives, including, for example, key materials, processes, production technologies, key customers, suppliers, and employees?

- What is management assuming about our ability to advance each of the current business drivers and new strategic initiatives over the long term, and how will we monitor those assumptions over time?

Leveraging this thorough understanding of the critical aspects of core business drivers and new strategic initiatives—through management interviews, surveys, or workshops—helps management identify risks and advance the organization’s business model and strategic plan. Here’s the place where sustainability and risk oversight intersect. Instead of driving the organization’s focus on sustainability using a number of related concerns, such as water, energy, or the environment (often referred to as “tree hugger” concerns), the focus is on those events or conditions that might impact the organization’s ability to sustain its core business drivers or new strategic initiatives over time. For example, what factors could keep the organization from sustaining key materials, processes, people, and technologies needed for the business driver or new strategy to succeed? How might its assumptions about its business model and strategic initiatives be flawed or change over time?

FACTORING IN DIFFERENT TIME HORIZONS

Integrating sustainability risk thinking into the context of strategy requires both a short-term and long-term perspective. Most leaders think about issues that may suddenly emerge in the near term affecting access to key inputs, products, technologies, or people. Thus engaging management in processes that focus on internal or external events that might trigger risks to the organization over the strategic plan horizon, which often only spans two to three years, is important and likely under way in most organizations.

Unfortunately, given the number of issues that might slowly emerge over longer periods of time (and given the corresponding time it often takes to address them), consideration of sustainability issues can’t be limited to near-term horizons, as illustrated by the Coca-Cola example. It’s important for management to think about issues that might emerge over the next 10 to 15 years, not just the next two to three years. For instance, in an effort to shift the focus from short-term to longer-term performance, Unilever CEO Paul Polman announced in 2009 that the company was no longer going to provide earnings guidance and quarterly profit reports. The initial reaction from the markets was harsh, driving down Unilever’s stock price by 25%, but eventually it rebounded to recoup the loss and more.

We recognize that this longer-term view is difficult to accomplish with today’s short-term-focused executive compensation plans. Yet Alcoa, for one, has been successful in incorporating shorter-term sustainability goals into its executive compensation plans, taking incremental, short-term steps in achieving its longer-term sustainability goals. Accordingly, the company has made a few significant changes to its compensation plans over the last several years. Specifically, for 2013, up to 20% of Alcoa’s variable compensation plan was tied to hitting certain sustainability targets that included safety, diversity in the workforce, and reductions in carbon dioxide emissions.

To help organizations see the intersection of ERM and sustainability, we coach executives on engaging in discussions about answers to the following critical questions, using both short-term (two to three years) and long-term (10 to 15 years) horizons.

- What might arise from internal or external events that could prevent the sustainability of core business drivers and new strategic initiatives over the next two to three years? What about the next 10 to 15 years?

- What might emerge that limits or eliminates access to key inputs that will be needed in the long term for the core business driver or new strategic initiative to retain its strategic value?

- What might emerge that restricts, eliminates, or displaces our ability to sustain key processes and technologies?

- What might impact the contributions and availability of key players/stakeholders to this process (such as suppliers, employees, customers, and regulators)?

- What new competitors may emerge to totally replace our products/services, manufacturing process, and/or distribution methods?

2. When developing strategic initiatives, executives usually have to make some critical assumptions. What environmental, social, economic, and industry events or trends might trigger changes in factors that support management’s key assumptions about the ability to sustain its core business drivers and new strategic initiatives?

As mentioned earlier, management can use a number of techniques to encourage this type of thinking, such as interviews with key executives, management workshops, or surveys. Some organizations have found a “pre-mortem” analysis to be an effective tool to prompt management’s thinking about issues affecting long-term sustainability of the business model. A pre-mortem analysis engages individuals in projecting a negative business outcome (a hypothetical business “death”) into a future point in time so that management can discuss what might occur between now and then—a prospective hindsight analysis, if you will.

Let’s return to our Coca-Cola example and assume you’re part of the Coca-Cola management team. A pre-mortem analysis would have you think about issues that might explain the company’s inability to achieve its 2020 Vision, which included doubling 2009 revenues. What resources, processes, technologies, regulations, people, or other key elements of the strategy failed to be realized, and how and when did management’s assumptions underlying that strategy go wrong? The answer could be revealed in any number of ways: A key resource might become unavailable, regulations or consumer preferences might change, an unanticipated competitor arises, or there’s significant climate disruption.

USING KRIS WISELY

With a prioritized focus on those risks most likely to impact the long-term sustainability of the business, management is in position to develop key risk indicators (KRIs) to proactively monitor internal and external events as they begin to emerge. KRIs give management a more forward-looking perspective of risks and opportunities that might be on the horizon so that organizations can respond strategically and ahead of the competition. The goal is to identify effective metrics for the most critical risks to the long-term viability of the business.

For example, in November 2010, Unilever launched the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan, which established three goals to achieve by 2020: (1) Help more than 1 billion people take action to improve their health and well-being, (2) Halve the environmental footprint of our products, and (3) Source 100% of our agricultural raw materials sustainably and enhance the livelihoods of people across our value chain. The overall vision for the company is to double the size of the business while reducing its environmental footprint and increasing its positive social impact. To measure its progress, Unilever developed both financial and nonfinancial key indicators that are aligned with these three goals.

CRAFTING A LONG-TERM STRATEGY

By positioning both risk management and sustainability thinking in the context of your organization’s current business model and new strategic initiatives, management has a framework for ensuring that its ERM and sustainability efforts provide strategic value. Such a framework helps management and the board structure their thinking so that they don’t become distracted by short-term issues that are less important than those impacting the long-term sustainability or viability of the business model.

Without an organizing framework such as the one we propose, management and the board could easily become confused about which sustainability issues are the most important to the organization. That’s because not all of them are relevant to what drives the value of an enterprise. As you can see from what we’ve shared with you, using a sustainability-informed strategic lens to think about the risks related to maintaining core business drivers and new strategic initiatives helps ensure that management’s investments in ERM and sustainability are positioned for long-term value, thereby making them a prized strategic tool.

March 2015