The role of the auditor is unique in the business environment. Usually when a company hires a consultant, the goals of the company and the consultant are consistent. In some cases, the role of the consultant is to act as an advocate for the company. Yet the very nature of the auditor/client relationship creates a certain degree of friction between the auditor and the client. Standards and regulatory authorities require the auditor to be independent, which often creates some misperceptions about the auditor. Management pays the auditor for an independent report assessing management’s financial performance and adherence to established accounting standards—a critical assessment, if you will—even though it’s against human nature to like criticism.

Some financial executives view the audit at best as a necessary evil and at worst as a threat. In fact, auditors want to avoid conflict as much as anyone else. Most auditors aren’t seeking confrontation; they think a good audit is one where there are few contentious issues and management’s judgments mirror their own.

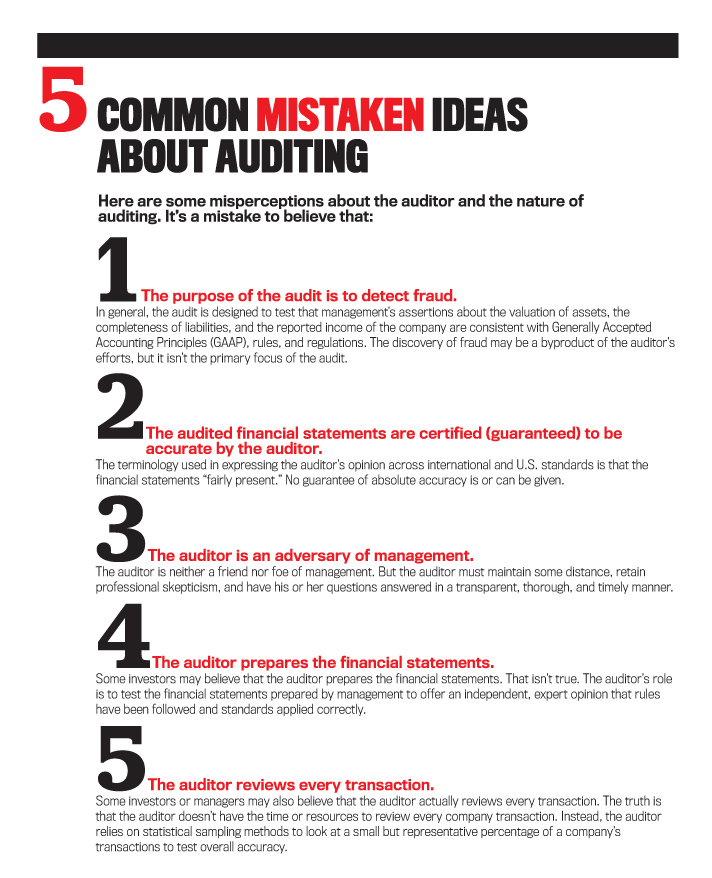

But financial executives and others often have some common misperceptions about auditing that can be stumbling blocks to working closely with auditors (see “5 Common Mistaken Ideas About Auditing”).

WHAT IS PROFESSIONAL SKEPTICISM?

One key to understanding the role of the auditor is the universal audit concept of professional skepticism.

Paragraph 13 of the International Standard on Auditing (ISA) 200, Overall Objectives of the Independent Auditor and the Conduct of an Audit in Accordance with International Standards on Auditing, from the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), defines professional skepticism as:

- “An attitude that includes a questioning mind,

- Being alert to conditions which may indicate possible misstatement due to error or fraud, and

- A critical assessment of audit evidence.”

The U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) has a similar definition.

Management determines when and how to record certain transactions. Professional skepticism, which assures that an auditor maintains independence, consists of making an independent determination of how the same transactions should be recorded in the company’s records. At that point, the auditor can make a comparison between his or her judgment and management’s actions. In reputable companies, the auditor’s assessment most often will mirror management’s actions.

THREATS TO PROFESSIONAL SKEPTICISM

The two big threats to an auditor’s professional skepticism are familiarity with management and the cult of personality.

The nature of auditing requires that the auditor maintain a certain distance from the client. Too much familiarity endangers both professional skepticism and a quality audit. Auditors trust their clients in the sense that no respectable audit firm wants to have the reputation of catering to dishonest or disreputable firms—but that trust doesn’t relieve the auditor of the responsibility to conduct the audit with a questioning mind.

ISA 200 notes that we can’t expect auditors to disregard past experience with management and those charged with governance. But the auditor must maintain professional skepticism despite believing that those charged with governance are honest and have integrity. Also, the auditor must not be satisfied with less-than-persuasive audit evidence when obtaining the reasonable assurance necessary to form an opinion on the financial statements. (See ISA paragraphs 15-16 at http://bit.ly/IAASBhandbook.)

That high standard underlies the International Accounting Standards Board’s (IASB’s) 10-year audit firm rotation requirement, which the IAASB follows, and the earlier seven-year audit partner rotation requirement. It takes basic human nature into account. If an auditor finds that management has been honest in the past, that builds a level of trust and the expectation that management will be honest in the foreseeable future. Professional skepticism mandates that the auditor resist this very human reaction because corporate or personal pressures on management might tempt the most honest managers to bend the rules in certain circumstances. The auditor is the last line of defense to keep management honest. That’s why he or she must verify what management reports.

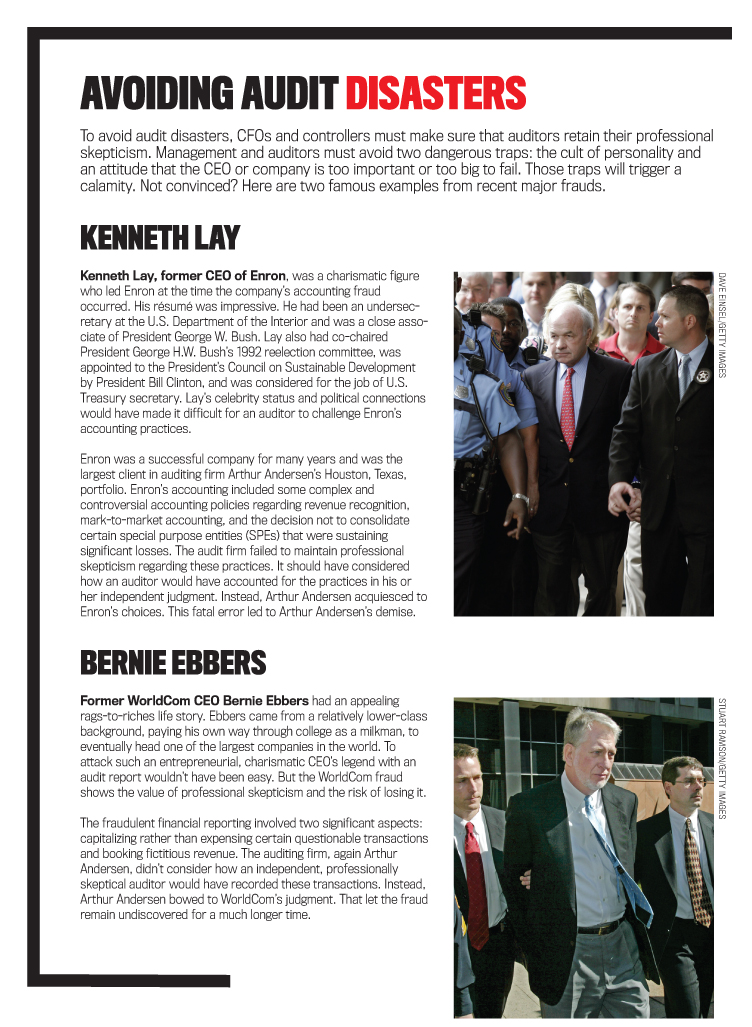

The cult of personality is a threat because CEOs are often charismatic figures, especially the entrepreneurial ones who have built their own companies. The auditor, being human, can easily fall under the spell of a charismatic CEO.

For two examples of major U.S. frauds where the cult of personality and a “too big or too important to fail” attitude played a role, see “Avoiding Audit Disasters.”

HOW WILL THE MANAGER/AUDITOR RELATIONSHIP CHANGE?

The latest PCAOB and IAASB standards are designed to ensure that auditors will maintain professional skepticism and not develop a personal relationship with management that is too close. At the same time, the standards mandate that the auditor develop a close but professional relationship with management to promote transparency and communication.

But the relationship of the CFO and controller with their auditor will change in certain ways. The IAASB’s “A Framework for Audit Quality: Key Elements that Create an Environment for Audit Quality,” published on February 18, 2014, recommends an increased interaction between the auditor and the preparers of financial information (see http://bit.ly/FrameworkAuditQuality).The result will be a closer working relationship between the auditor and a company’s financial staff. It’s important to recognize that the purpose is to increase the auditor’s understanding of how the financial information is acquired and consolidated and how judgments are made. That will create a greater understanding of the risks and specific judgments involved.

The PCAOB’s requirement that auditors monitor transactions with related parties more closely—especially those with company executives—may be a cause of friction between auditors and executives (see “Audit Regulators Say Get More Involved!”). The intent of this monitoring reflects the PCAOB’s concern that executive stock trading may signal insider knowledge of the company’s future events. Kenneth Lay notoriously unloaded much of his Enron stock in the months before Enron’s bankruptcy. These kinds of executive actions may signal risks.

CFOs and controllers should view this closer auditor monitoring of their actions from the perspective that they have nothing to hide. The only executives who should feel threatened by this requirement are those who have something to hide. If CFOs and controllers recognize the PCAOB’s intent and management ensures clear communication between auditors and executives, the transition will be less painful.

The IASB’s audit firm rotation requirement of 10 years can be increased to 20 years if the audit is put out to bid, but that still imposes a limit on the auditor/client relationship. While this limit may not seem onerous, it changes the dynamic between the auditor and management by making the relationship impermanent. The auditor will begin to feel that his or her work may be subject to oversight (review) by a competing firm, which will make the auditor more careful in exercising professional skepticism. In addition, the company will begin to view its relationship with the auditor as more transient. Once every 10 years, the company will have to build trust and a working relationship with a new audit firm. The company will be motivated to establish procedures and protocols for this predictable event. Right now, auditor change is often a rare and chaotic event.

UNDERSTANDING THE AUDITORS ROLES

To understand what auditors want, bear in mind that the auditor has three key roles.

First, the auditor must expedite efficient and fair access to financial markets. If all companies competing for resources in financial markets are on an even playing field, financial resources can be allocated efficiently among competing firms. In an efficient market, this maximizes overall returns. The auditor’s role here is to ensure that all companies are playing by the same rules and to minimize cheating.

The auditor’s second role is to report to shareholders. Management creates the financial reports, and the auditor provides a second set of eyes to assure that management is being fair and direct in assessing and reporting the company’s performance. In part, this serves to prevent management from reporting biased results to shareholders.

The auditor’s third role is to serve as a part of the regulatory mechanism. The auditor is a licensed expert in financial reporting and disclosure matters, assuring that the company’s financial reporting is in compliance with the rules established by the IASB and/or the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB).

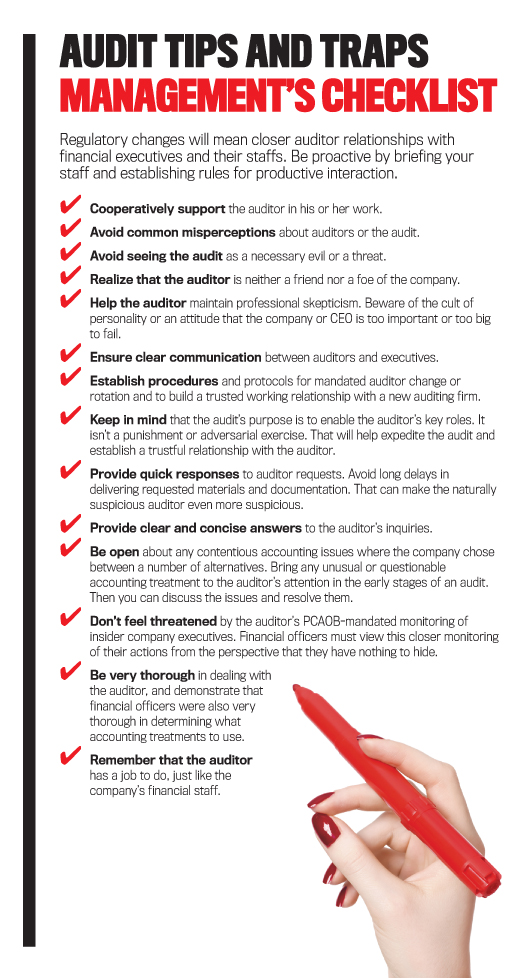

CFOs, controllers, and their staffs must understand that the purpose of the audit process is to enable the auditor’s key roles. It isn’t a punitive or adversarial exercise. Keeping that in mind will help expedite the audit and establish a trustful relationship with the auditor. By professional standards, the auditor is neither a friend nor an enemy to the company.

WHAT DO AUDITORS WANT?

The auditor needs a relationship with a client’s CFO and controller that has some very special characteristics: transparency, thoroughness, and timeliness.

Experienced auditors are human, but they are also generally better-than-average judges of character. Being a good judge of character is an essential quality in a good auditor. Transparency is the first quality an auditor seeks when developing and maintaining a good relationship with a client’s financial officers. This means the financial officers must provide clear and concise answers to the auditor’s inquiries, but it can extend beyond that. For example, it’s best to be open about whether there are contentious accounting issues where the client company chose between a number of alternatives. The auditor will probably discover it anyway. A good auditor will find any discrepancy that may be material (i.e., can affect the overall accuracy of the financial statements).

The proper way to handle a contentious accounting issue is for the CFO and controller to bring any unusual or questionable accounting treatment to the auditor’s attention in the early stages of an audit. Then they all can discuss the issue and resolve it. If financial officers answer the auditor’s questions directly, without trying to hide something or cloud the issue, then the client is likely to get fair consideration.

But if the auditor discovers that a questionable treatment wasn’t brought to his or her attention by the financial officers, a climate of distrust is created. Then, at the very least, the auditor will look for similar instances and be extremely conservative in his or her judgments.

It’s also important for financial officers to be very thorough in dealing with an auditor and to demonstrate that they were also very thorough in determining what accounting treatments to use. If a CFO and controller can clearly show that they considered and rejected other alternatives in their decision-making processes, the auditor will take that into consideration. Yet if the reasons for a chosen accounting treatment are obscure or confusing, the auditor will be more suspicious immediately. A lack of thoroughness can lead an auditor to question other management decisions.

Finally, timeliness is important for both the auditor and the financial officers. An auditor needs to work as efficiently as possible to complete the work on time. This is one area where the company and its auditor share the same concern. The auditor wants to complete the audit as much as the company does. It’s frustrating to an auditor when completion is held up while waiting to resolve a few issues or deal with incomplete documentation. Quick responses to auditor requests also build trust, while long delays in getting requested materials and documentation can make the naturally suspicious auditor even more suspicious.

PREPARING FOR CHANGE?

As you can see, the latest auditing regulations mean that CFOs and controllers will have to work more closely with auditors. For help in preparing for this change, see “Audit Tips and Traps Checklist.”

Keep in mind that the auditor has a job to do, just like the company’s financial staff. Working closely and cooperatively with an auditor will speed up the process and avoid the trap of an unpleasant and risky adversarial situation.

July 2015