How can you find out? Each year, companies commit sizable resources to marketing and advertising in the hope that good things will happen. A year or two later, when sales and profits have in fact increased, the chief marketing officer (CMO) will want to take credit that it was his or her marketing project that generated these increases.

But if you’re the chief financial officer (CFO), wouldn’t it be desirable if you could measure the results of your company’s marketing decisions and commitments? Rather than relying on self-serving statements by marketing executives, wouldn’t it be better to have objective financial data? What if you had a tool that could help measure the impact of marketing expenses before the funds are committed?

Good news! A financial tool for measuring the value of marketing expenditures is available: brand value.

Measuring brand value can give a CFO an objective and accurate way of evaluating past marketing expenditures and can help quantify the expected benefit of future marketing expenditures. And let’s go one step further. The CFO and the CMO can work together on this project.

WHAT IS BRAND VALUE?

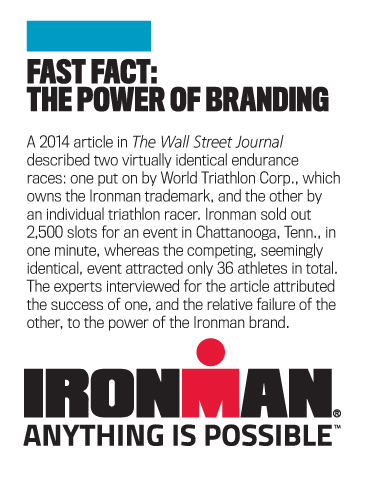

Millward Brown, a global advertising and marketing firm, says that brands “embody a core promise of values and benefits consistently delivered.” The most recognizable brands, the agency explains, are meaningful (meet the individual’s expectations and needs), different (unique and trend-setting), and salient (they come to the consumer’s mind as the brand of choice). Better still, good brands increase both sales and margins, thereby increasing profits.

Essentially, brands create value in two ways. They increase sales volume when consumers choose to buy a well-known brand over a lesser-known brand or an unknown generic product offering similar features. For example, faced with a cooler of soft drinks, many consumers would choose a Coke over an RC Cola, even if the Coke were slightly more expensive. In a retail food store, most consumers would choose Coke over the store brand. If the choice were between Coke and Pepsi, however, both well-established brands, then it becomes a matter of personal choice in the same way that some people are self-proclaimed “Ford” drivers and others, “Chevy” drivers.

Second, brands often increase margins. Again, even at a price premium, most consumers would likely choose Coke over RC Cola, which means that brands not only increase sales volume, but margins as well, because the owner of the branded product can command a higher price for an essentially similar product or service.

In short, brand recognition by customers usually results in higher sales or greater margins and often increases in both volume and margins. But brand values aren’t static. Coca-Cola, for example, which just a few years ago was rated the world’s most valuable brand, has been knocked down a few places in the face of challenges from Apple, Google, and McDonald’s, among others.

Brands also require continual support. Think of Woolworth (now Foot Locker). There’s a school of thought that businesses must grow or die; the same appears to be true of brands. Brands are either supported and grow, or they’re neglected and soon fade away—like Blackjack gum, Pan Am, or Oldsmobile or Studebaker cars.

WHY SHOULD CFOS CARE?

Using the example of a well-established athletic shoe company recognized by serious runners, let’s assume that our first valuation of this brand is $110 million, give or take $10 million.

As a CFO or controller, just what does the initial dollar value of the brand signify to you? First and foremost, this is a company asset. An additional $100 million in brand assets is like adding another $100 million to the firm’s equity. Lenders see it this way, too. For example, Ford Motor Company is one of the many companies that have borrowed money using their trade names and their trademarks—in Ford’s case, including its iconic blue oval logo—as collateral.

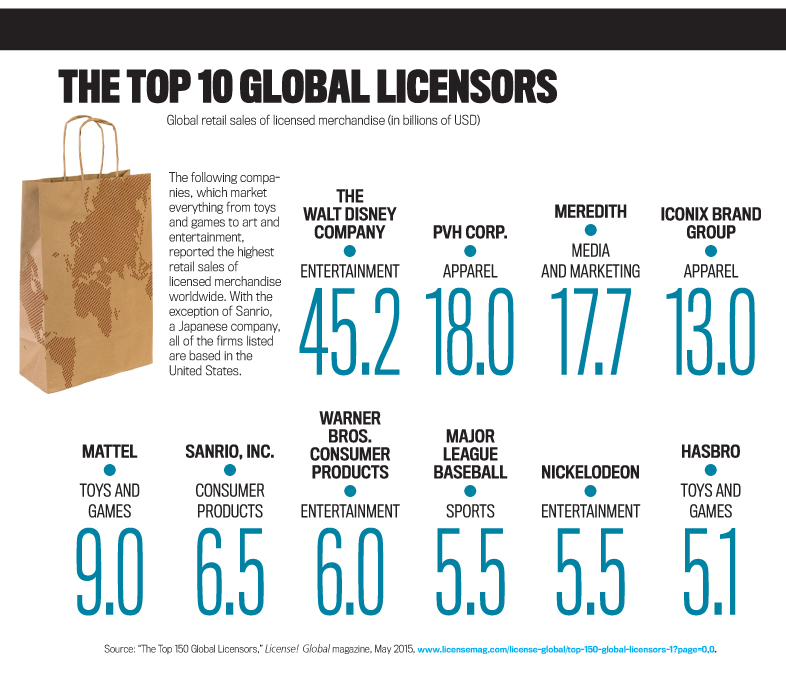

Another use of the initial brand value is to stimulate thought about licensing. Just look around on any given day and see how many instances of licensing you can spot. Licensing is big business, and the first step is to identify what your brands are worth to you. Then, and only then, can you approach others about licensing your name. For example, a leather coat manufacturer may be willing to pay 6% of its revenue to be able to engrave or stitch the Harley-Davidson logo on the back of its jackets. In a Harley store, the selling price will certainly be higher than that of the identical coat, without the logo, sold at Kohl’s. But the coat manufacturer’s owner expects to get more sales and higher margins from the logo and at least recoup the licensing fee.

Finally, your brand’s initial valuation represents an indication of what all of your previous marketing plans have accomplished—the sum total of all corporate efforts in the past.

Yet without a strong and continuing marketing effort, the value of a brand is likely to remain low. It was reported recently that the owner of the Cracker Jack trade name, Frito-Lay, had spent nothing on marketing for years and that the brand had almost disappeared. The same report, however, indicated that Frito-Lay was now going to invest marketing dollars in growing Cracker Jack because so many potential customers still remembered the old line from “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” about “Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack…” Frito-Lay was smart enough to realize that the Cracker Jack brand still had some value and would be easier to resurrect than have the company start from scratch marketing a new name for caramelized popcorn.

At this point, you may be asking yourself, “Which comes first, the brand value and then the financial strength, or is it the financial strength that carries the brand value?” Certainly each influences the other, but we believe that the brand determines financial results. We have valued almost 1,000 different companies, and in nearly every instance senior management attributed their own success to customer service, which in turn is the company’s brand.

WHAT THE REGULATORS SAY ABOUT BRAND VALUE

There’s nothing in the accounting and financial reporting rules that prevents a company from disclosing intangible asset values as part of the nonfinancial aspects of financial communications. This can be done in the Management’s Discussion and Analysis (MD&A), provided that there’s an adequate explanation of what’s being disclosed and that the amounts shown are supportable.

We and other valuation specialists have been measuring the value of certain brands for many years. The problem is that current Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP) permits brand values to be shown only after a merger and acquisition (M&A) has been completed. When Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No. 141, “Business Combinations,” and SFAS No. 142, “Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets,” were issued in 2001, companies for the first time were required to report the values of brands acquired in a business combination. (Those brand values are updated every year for subsequent impairment testing.) Prior to that time, some Internal Revenue Service (IRS)-related valuations permitted brand values to be determined for tax purposes, but, as a general rule, brands and other intangible assets weren’t on GAAP statements, so CFOs, creditors, and investors simply neglected them. That’s a shame because a CFO can measure the effectiveness of his or her company’s marketing plans by periodically measuring brand values.

Even after 2001, companies were prohibited from recognizing the values of brands they themselves had developed. Many an analyst has commented ruefully that the single most valuable asset of the Coca-Cola Company—its brand—isn’t disclosed to investors anywhere. In the absence of the ability to treat brands as a real asset on the financial statements, CFOs and controllers have been forced to focus on other performance measures, such as those dealing with inventory and research and development (R&D).

It’s ironic that intangible assets are required to be valued in M&A transactions yet can’t be valued (and shown in the financial statements) in the absence of an M&A transaction. Many observers have commented on this anomaly, but there’s no evidence that any of the major regulatory authorities, including the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), or the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), has the stomach to go down this path any time in the near future.

At one point, the FASB indicated it would start a project dealing with self-developed intangible assets, including brands. Unfortunately, this project never got off the ground. Our opinion is that conservative accountants and auditors feared that if companies were permitted to value their own intangible assets, the risk of abuse would be too great.

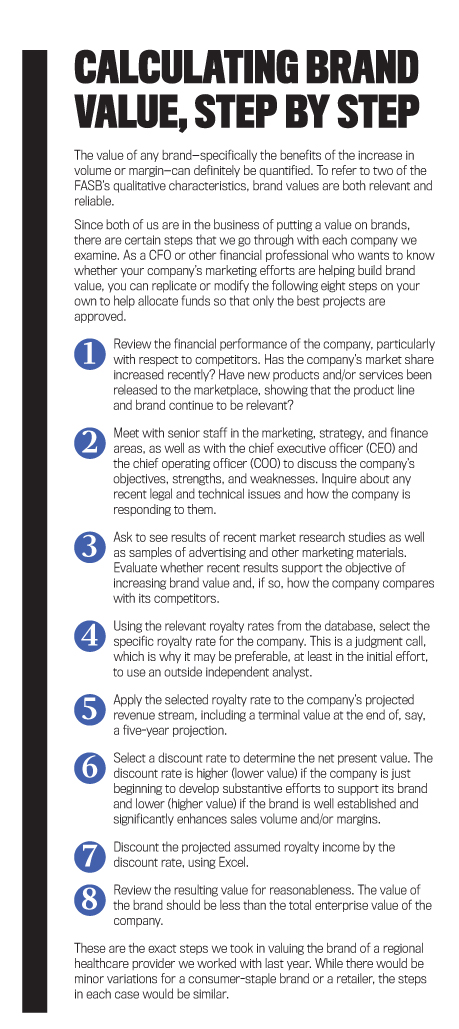

EXAMINING THE METHODOLOGY

The mechanics of determining brand values are relatively simple: You obtain an appropriate “royalty rate” from one of the two major databases (RoyaltySource and ktMINE) and apply it to the projected sales of the branded product (sales projections should have a terminal value after the last calendar year in the forecast). Then you discount the projected royalty income, using Excel, with an appropriate discount rate.

The only issues are the choices of royalty rate and discount rate. For royalty rates, there may be some judgment involved because, no matter how extensive the database, there’s never an exact comparable. But usually it’s possible to find several that are close. You can finesse things by using the median of the reported rates, sometimes applying just a little judgment to allow for the strength (or weakness) of the subject brand.

The second judgment area is the discount rate, which in practice can have a substantial impact on the absolute dollar value. Many companies would be tempted to use their weighted average cost of capital (WACC), or internal hurdle rate. It’s usually possible to support a discount rate lower than the WACC since royalties are uniformly based on sales, not gross profit or operating profit. Generally there’s greater accuracy in measuring sales than in projecting profits—hence a lower discount rate may be more appropriate.

The actual calculation involves applying the chosen royalty rate, which doesn’t usually change much from year to year, to the prospective future sales of the branded product or service. These projected royalty payments are then discounted back to the present at an appropriate discount rate. This rate, too, would change only slowly over time.

While the mechanics of calculating a brand value are very straightforward, some CFOs might prefer to use an outside, independent valuation specialist, at least in the initial development of brand values. Such specialists often have valued literally hundreds of brands, are familiar with the databases, and can support the choice of an appropriate discount rate. Moreover, an outside perspective can be helpful when there are disagreements within the company.

After the initial determination, however, subsequent estimates of brand values can often be carried out internally, saving both time and money. The key, of course, is that measuring the value of marketing efforts requires the active involvement of both the marketing and finance departments. To be successful, the process can’t include one without the other.

AN INEXACT SCIENCE

Appraisals of brand value are made for two reasons. In the case of marketing, brand values—and changes in brand values—can provide insight into current and prospective marketing decisions. Second, the brand value provides a picture at a point in time of what the marketing team has accomplished.

Even though we and the partners at our businesses are very deliberate in the way in which we attach a dollar value to a company’s brand, appraisers don’t always agree. If two independent appraisers are given the same assignment, with the same assumptions, they should come within 10% of each other, but they’ll never arrive at identical answers.

In general, differences in two appraisers’ respective values usually can be traced back to differing assumptions about the future. Reasonable people can disagree about the likelihood of future events, and of course nobody really knows for certain what will happen. That said, the only pushback to brand valuations will likely come from marketing executives who may feel that the CFO has been unduly conservative (or possibly too optimistic) in his or her estimate of brand value.

WHAT THE CFO GAINS

Currently, CFOs can only object to marketing plans they disagree with, and executive management will usually support marketing, assuming, “What do financial people know about marketing anyway?”

But if the marketing department’s plans are tied to increases in brand value, then finance will be an integral part of planning for marketing expenditures. That said, executive management doesn’t want the CFO making marketing decisions alone, just as there’s no interest in having the CMO prepare SEC filings.

As we mentioned earlier, a good brand increases both sales and margins. Therefore, any future funds to be spent for marketing should be measured directly, in terms of expected sales, improved margins, or both. If marketing expenditures do increase sales and/or margins, then the value of the brand will also be enhanced, probably offsetting a significant portion of the firm’s out-of-pocket marketing costs. In other words, well-focused marketing can pay for itself as long as we measure the increase in value of the intangible asset—in this case, the brand.

But if sales and margins fail to track the marketing plan—if there is no net improvement in brand value—management can intervene more quickly, either to reorient marketing expenditures or to recommend other changes. A good way to look at this is to require that marketing costs have a positive impact on brand values. This measurement tool, if applied with judgment, should bring many ill-considered marketing/advertising proposals down to earth.

FORECASTING BRAND VALUE

Increases in brand value could (and should) be forecast before every major marketing program. Then, periodically, a formal brand valuation study can be performed. This will either confirm the original projections or point out where they went off track.

Again, think of brand values as a function of sales volume and margins, which are forecast routinely. What’s missing is the quantification of the increase in brand value relative to what’s being spent on marketing. Keep in mind that there will never be a 1:1 correlation. But the fact that increases in brand value can offset part or all of what your organization budgets for marketing is something that both marketing and finance should jointly agree on. Both functions will gain something as a result.

Finally, there’s a strong impetus for companies to develop brand values and disclose them as part of any financial analysis, or MD&A for public companies. There’s nothing in U.S. GAAP that precludes such disclosure outside the audited financials, and shareholders and lenders will be pleasantly surprised at the dollar amount of this “hidden” asset.

July 2015