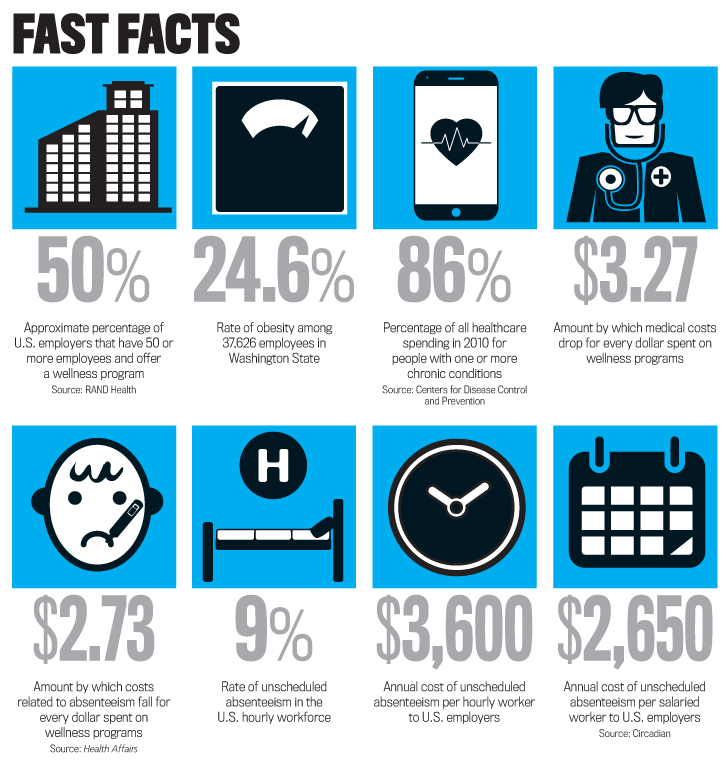

Employers aren’t doing this all in the name of altruism, of course. Even the most basic wellness plans improve the overall health of companies by saving money and boosting the bottom line. In a meta-analysis of literature on costs vs. savings associated with such programs, “Workplace Wellness Programs Can Generate Savings,” published in the journal Health Affairs, researchers found that medical costs fall by about $3.27 for every dollar spent on wellness programs and that absenteeism costs fall by about $2.73 for every dollar. In most cases, according to one industry leader, it takes about two to five years after the initial program investment to realize these savings. Moreover, companies with established wellness programs are in a better position than companies without such programs to bargain with health insurance companies for a discount on premiums because they can demonstrate less risk among those employees who are part of the program.

According to numerous estimates, healthcare costs have nowhere to go but up. In 2011, for instance, the Kaiser Family Foundation predicted a 9% annual growth rate. As health insurance costs continue to rise, more businesses will consider starting wellness programs or improving existing ones. But despite its many advantages, a well-intentioned wellness program can fail to catch on with employees if it isn’t fully planned, implemented, and supported. Employees won’t benefit from it, and the company will have wasted time, money, and effort. To help keep this from happening, we’ll discuss how a company should go about planning and implementing a wellness program. Then we’ll highlight some of the benefits and challenges to consider in the process.

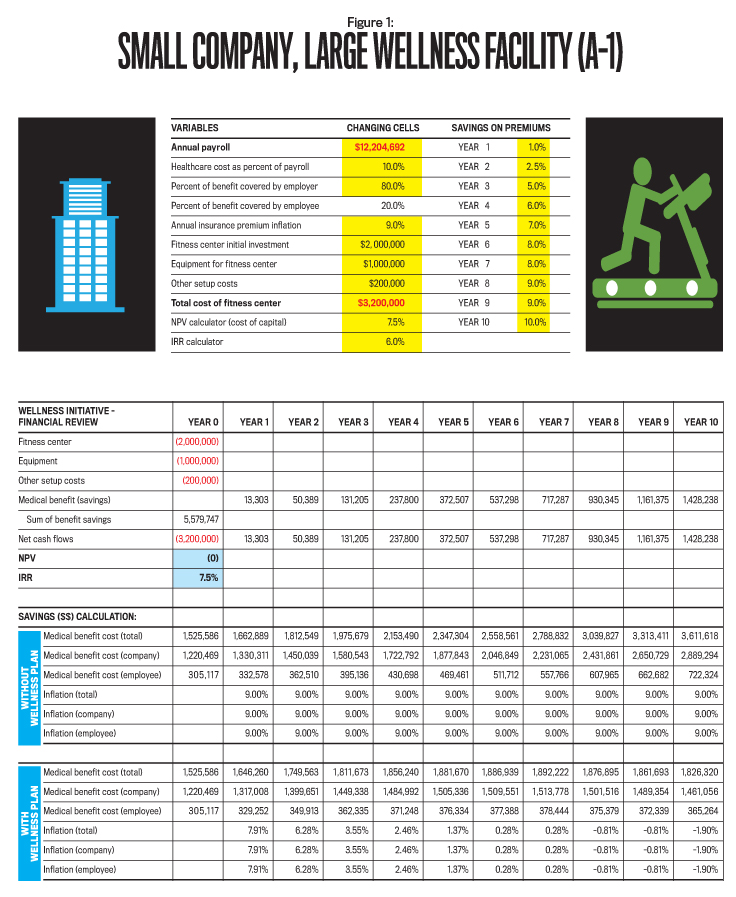

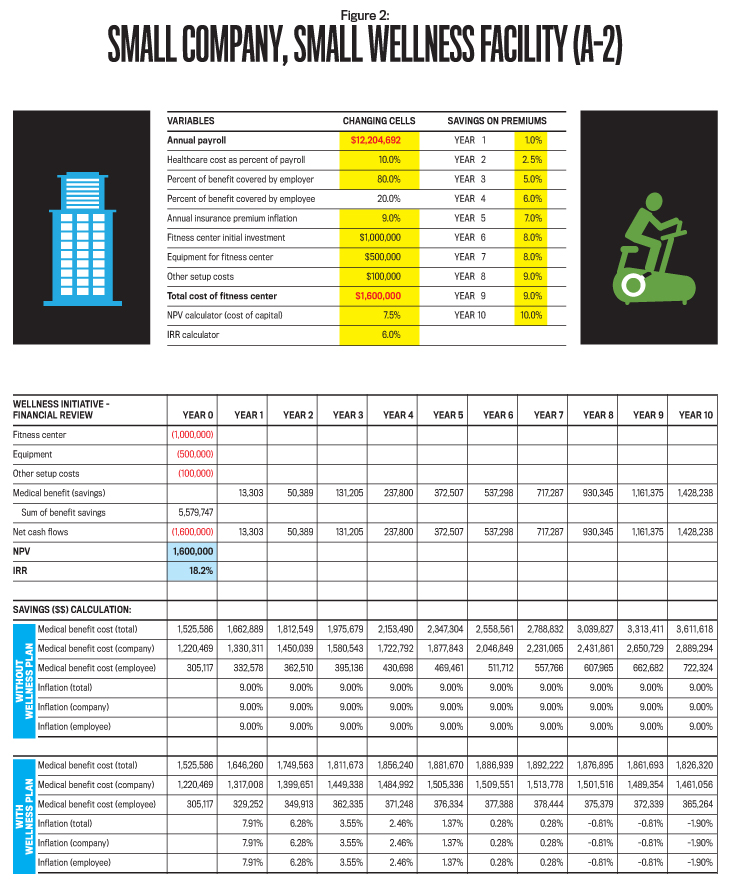

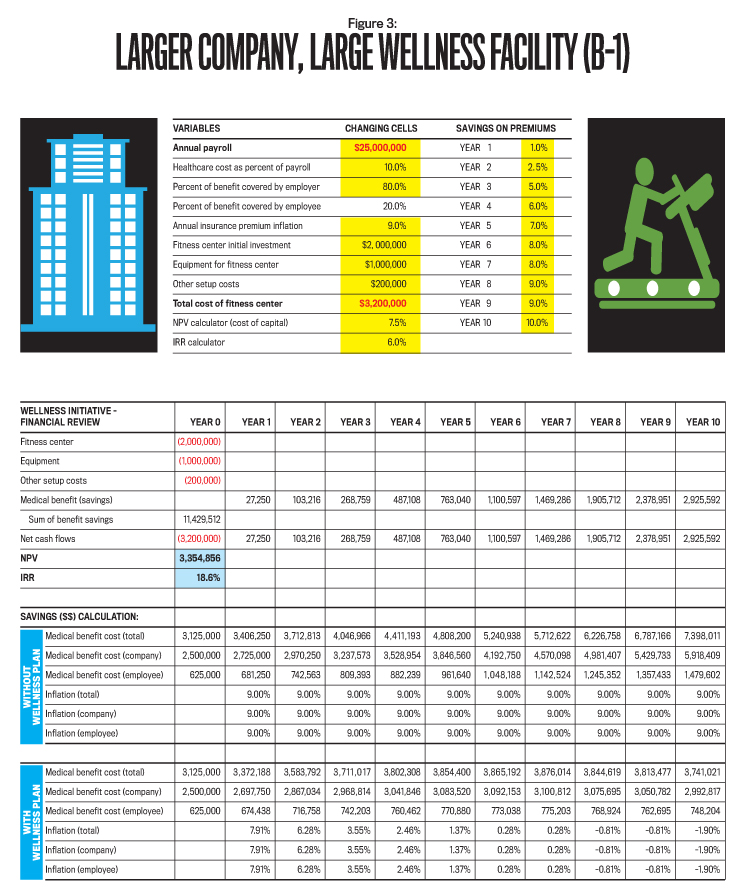

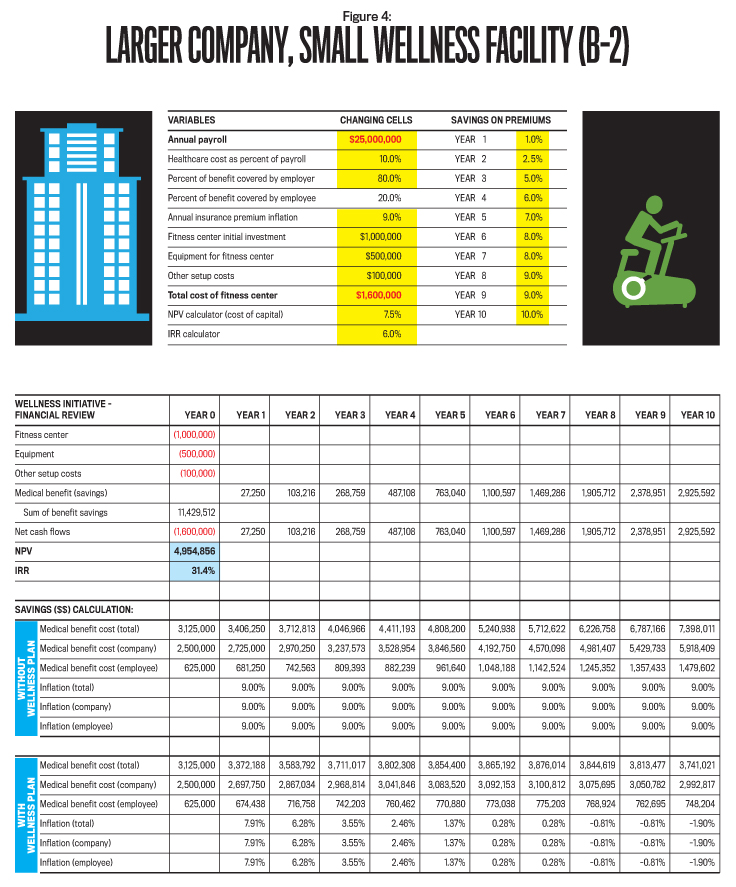

As management accountants and other financial professionals whose job it is to support proposals and other ongoing initiatives with numbers, you’ll certainly want evidence of the financial benefit of wellness initiatives over time, which is the main focus here. We’ll share with you a model we developed that allows you and other decision makers to input variables such as annual payroll, inflation rate, insurance discount rates, and costs associated with constructing a wellness facility. There are unlimited combinations, but we’ll use several unique scenarios to illustrate the return on investment (ROI) and internal rate of return (IRR).

Our model is software-based and transferable to any size company because it allows for multiple variables. We’ve found it very useful in forecasting ROI and IRR for a company—yours, perhaps—that’s considering the effect of the time value of money on investment in a wellness program.

CONSTRUCTING A WELLNESS PROGRAM

Implementing a wellness program requires a cultural change for most companies. Employees value their personal time, so anything a company does to influence the way employees spend their free time might be seen as intrusive. Smaller companies tend to have a more close-knit culture, so it may be less difficult for them to implement wellness programs.

Either way, small companies have a greater incentive to manage their healthcare costs since they’re more impacted by medical claims and don’t have the economies of scale to spread out increases in premiums that large companies do. Smaller companies also feel more of an impact in terms of productivity when employees call in sick, whereas larger companies can absorb a greater number of worker absences because of illness.

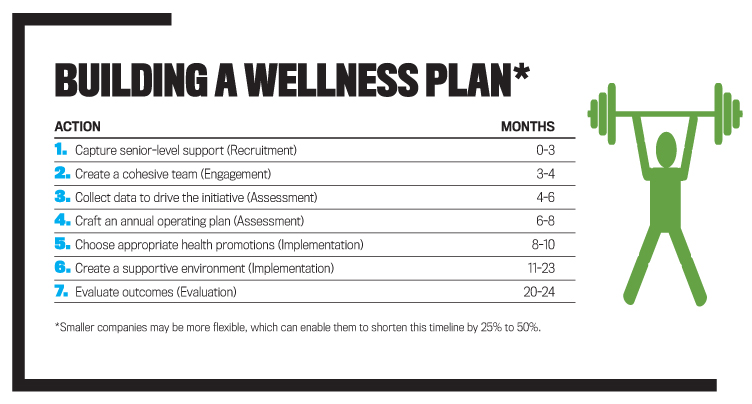

In the mid-1990s, the Wellness Council of America (WELCOA), led by David Hunnicutt, began forming the cornerstone of the workplace wellness movement. In a 2006 issue of Absolute Advantage, he and his team presented “WELCOA’s 7 Benchmarks of Success” of a further-developed and refined dynamic process for helping organizations implement “best-in-class” workplace wellness programs.

SEVEN BENCHMARKS OF WELLNESS PLANS

The seven benchmarks help planners and members of the finance function understand that it’s important for company leaders to communicate expectations regarding wellness plans and to follow through by allocating the necessary resources. If the C-suite isn’t solidly behind the program, it isn’t likely to gain much traction with the rest of the employees.

- Capture senior-level support. Again, a successful wellness program requires the support of executives as measured by their own participation in the program. (Is the CFO lifting weights or on the treadmill at lunchtime along with the crew from the mailroom?) Strong support from the CEO, middle management, and the people who coordinate the wellness program is essential.

- Create a cohesive team. To form a tight-knit wellness team, the team’s composition and method of operating are critical. It’s equally important to make sure the team possesses the resources to carry out the plan. If they aren’t adequately funded, they aren’t going to get the job done.

- Collect data to drive the initiative. With senior-level support and a team in place, the next step in implementing a wellness program is to acquire data. Collecting and analyzing data drives a wellness initiative and produces results that will contain costs and improve employee health. Management must also understand the demographics of their employees, including the age, gender, and geography of the workforce.

Managers should survey their employees to determine what sorts of programs appeal to them the most, then use the data to classify the workforce’s biggest health risks, such as chronic diseases, accidents, inactivity, poor diet, smoking, and other lifestyle choices. Costly health problems like cancer, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases often can be attributed directly to behaviors and lifestyle choices. Changing these behaviors before it’s too late can reduce the incidence of these diseases.

Then companies should use data to establish goals and make workplace changes that remove barriers to healthy choices. They also should find out which employees are missing work and for what reason(s). Only after data is collected and analyzed can a wellness plan be designed. Over time, as the needs of employees change, new data should be collected to capture feedback and make necessary adjustments.

- Craft an annual operating plan. This requires employers to lay out a methodology for the program. The operating plan is the document that communicates what the program will accomplish. It provides organizational and individual alignment and ensures everyone moves in the same direction to achieve unified goals. Without a plan, organizations suffer from fragmentation as individuals go their own way and do their own thing. The operating plan allows for organizational and individual empowerment and serves as an accountable communication channel with senior executives. It also is important in the event of turnover in key positions related to the company’s wellness initiative because it can prevent the loss of time, energy, and resources when orienting a new team member.

- Choose appropriate health promotions. During this stage, wellness team members should encourage the company to think in terms of its unique employee demographics in addition to the organizational mission and corporate culture. Examples might include which programs to offer or how intensive intervention will be (awareness, education, behavior change, cultural enhancement). In addition, now’s the time to decide how often certain programs will be offered and to whom (spouses, dependents, retirees).

Finally, this is the stage to think about what incentives to use to increase participation in your wellness program. Will employees receive free gym memberships? Are they eligible to win prizes or other recognition—such as additional paid time off—for losing weight or improving their numbers (blood pressure, cholesterol, etc.)?

- Create a supportive environment. The company should take steps to encourage its wellness plan members to increase their physical activity and to reduce tobacco use. They should promote better nutrition by thinking about vending machine offerings (or even getting rid of the machines) and strive to improve workstation ergonomics. They should try to reduce on-the-job injuries and off-the-job use of alcohol and other drugs. Programs that help employees better manage job-related stress and those that increase participation promote good health and a better environment.

As we alluded to earlier, a number of healthcare management programs offer discounts and cash reimbursements for healthy activities in an effort to encourage employee involvement. HealthAmerica’s Learn & Earn Wellness Education Refund Program is one plan that offers members a refund on approved health education classes, such as those centered on nutrition and wellness, smoking cessation, and weight management.

- Evaluate outcomes. The last step of implementation is to set measurable targets and carefully evaluate outcomes. The only way to know if the initiative is working is to track progress. By measuring participation, managers know what’s working and what isn’t. If part of the program isn’t working, adjustments can be made to the plan as with any other business project. This leads to improvements in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors that enhance the measures of risk factors, plus it allows the company to control and adjust the physical environment and the corporate culture in a way that augments productivity and ROI.

Looking at these seven benchmarks, it’s evident that a wellness plan is a long-term initiative that needs to be in place for years to bear fruit. The number of years varies depending on each company’s unique characteristics as well as its resources, implementation methods, and commitment.

Tallying the Benefits

To present the business case for investing in employee health, an article in the December 2010 issue of Harvard Business Review, “What’s the Hard Return on Employee Wellness Programs?” by Leonard L. Berry, Ann M. Mirabito, and William B. Baun, examined existing research and then studied several organizations across a variety of industries. These organizations’ wellness programs have systematically achieved measurable results. Harvard researchers asked roughly 300 people, including many CEOs and CFOs, about what works, what doesn’t, and their program’s overall impact on the organization. From these interviews, they identified “six essential pillars” that are common to a successful, strategically integrated wellness program in companies large and small: engaged leadership at multiple levels, alignment with the company’s identity, a broad and highly relevant design, broad accessibility, internal and external partnerships, and effective communications. Berry, the article’s lead author, says that these pillars can lead to outcomes that foster lower costs and that the savings on healthcare expenditures alone make for an impressive ROI.

A number of studies show that healthy employees are able to manage stress better, which makes them more productive and less likely to call in sick. Internal studies at DuPont and General Mills, for example, found a 14% to 19% reduction in absenteeism after the companies implemented a comprehensive wellness program. General Electric reported an even higher decrease of 45%. Employees enjoy higher morale, pride, trust, and commitment to the company, which contribute to a vigorous organization. This gives companies an advantage in recruiting and retaining high achievers.

Wellness programs have been linked to other advantages as well. Many employers credit wellness programs for productivity gains in areas such as reduced errors, improved efficiency, and better decision making. Quantifying the improvement in an individual’s ability to perform is difficult, but several years ago NASA found that the productivity of sedentary office workers decreased 50% in the final two hours of the day while exercisers worked at full pace all day.

Once employees are participating in a program, the company begins to benefit financially. Healthy workers require less medical care, which translates to lower medical insurance costs. For example, prior research has shown that healthcare costs are as much as 30% higher for smokers than for nonsmokers. Employees with bad diets cost 40% more in health claims than those with healthy diets. People who are 20% above their recommended body weight have higher levels of inpatient hospital care than do those with any other health risk. In comparison to people at normal body weight, overweight people visit the hospital 140% more often.

These statistics demonstrate that healthy people are less expensive to insure than unhealthy people. When people eat right and exercise, they make the most of their minds and bodies, and they generally reduce their health risks. Another benefit of a wellness program is the sense of solidarity that develops between participating coworkers. Having lunch together, motivating one another to go to the gym, and participating in various activities outside the work setting are potent experiences. In this capacity, wellness programs act as team builders.

Offering wellness opportunities to employees is a good first step. But since employees account for only 30% of healthcare costs, while their dependents account for the remaining 70%, all aspects of the wellness program need to reach the families of employees to be fully effective. Nevertheless, only 30% of wellness programs extend to spouses and dependents. We’ve found that companies that include families in their wellness initiatives enjoy a significant competitive advantage in recruiting and retaining gifted employees.

What to Watch Out For

Making the investment in a wellness plan can be expensive, but choosing the wrong vendor or making mistakes in program implementation can be even more costly. That’s why it makes sense to partner with a nationwide provider that knows the business and can help encourage participation in the programs. A good place to start is the nonprofit Corporate Health and Wellness Association (www.wellnessassociation.com), which can assist in providing wellness training and certification programs for employers.

As mentioned earlier, offering a wellness opportunity to employees is a start, but if a majority of them don’t use the program, it’s destined to fail. Moreover, skeptics emphasize that too few employees take advantage of wellness programs. Too often, they say, the employees who are willing to take part are those who are already health conscious, while the workers who need it the most are the ones most likely not to participate.

Setting up these programs isn’t inexpensive, either. Initiatives that include features such as a fitness center, a cafeteria with healthy food offerings, and a program of health screenings all consume company resources. Recognizing cost savings from wellness programs must therefore be a long-term strategy; cost savings will only accumulate over time when the benefits of good nutrition and exercise have had time to take effect. The size and timing of the results vary from one company to another and are difficult to determine given our current environment of rapidly inflating medical costs.

Another potential negative is a privacy issue. Some employees aren’t comfortable with their employers tracking their health and personal activities. Smokers or people who are overweight fear they’ll have to pay higher healthcare premiums and that their lifestyle choices may be held against them if they try to advance within the organization.

Even successful wellness programs with high participation and good initial results may have a long-term weakness: increasing life expectancies. People continue to enjoy longer lives, but pension systems haven’t been adjusted accordingly. In particular, retirement ages and funding assumptions for pensions don’t fully reflect the impact of longer lives. Pension plan sponsors have begun to look at ways to protect against longevity risk. Although longevity risk is a relatively new aspect of business, there are now a number of “de-risking” solutions available, allowing companies and pension plans to address longevity risk on their balance sheets.

CRUNCHING THE NUMBERS

In this section, we’ll examine the financial effect of a wellness initiative on medical insurance premiums over a 10-year span. The model illustrates the potential for healthcare cost savings in multiple scenarios, each of which allows for changing input variables so companies can achieve a balance suitable for their unique needs.

As a baseline, let’s assume that each company will spend 10% of total payroll, or $2.5 million, on medical insurance premiums. This dollar amount is 80% of the total cost of the premiums, with employees responsible for the remaining 20%. As mentioned earlier, the Kaiser Family Foundation predicts a 9% annual growth rate in healthcare costs. In the scenarios that follow, medical costs are growing more rapidly than annual employee pay increases. As an incentive for employees to share responsibility for the cost of their healthcare premiums, the company shares the increases and decreases in costs with employees. Savings because of the wellness program are shared as well.

In each analysis, we use a gradual scale of savings on medical insurance premiums over a 10-year period. The insurance company offers an incentive by lowering premiums by 1%, with the promise of greater discounts in subsequent years. They’ve agreed that if the company shows significant utilization of the program and a reduction in claims by year 10, the premiums will be reduced by as much as 10%.

In scenario A-1, the company employs 120 full-time workers earning an average of $100,000 each, putting annual payroll at a little more than $12 million. The company is considering a $3.2 million facility from which to manage and operate the wellness initiative. This will be a one-time expense in the first year. (See Figure 1.) For scenario A-2, we changed only the cost of the wellness center to demonstrate the effect on ROI and IRR if the company decides on a smaller wellness center at half the cost of the original plan. (See Figure 2.)

Small Company, Big Savings

Based on the analysis in scenario A-1, the small company can break even on a large, $3.2 million wellness investment because of an annual reduction in insurance premiums over 10 years. In the 10th year, the IRR is 7.5, and savings on premiums are more than $5.5 million. Net present value (NPV) is zero at this level of investment. A smaller company or more expensive wellness center wouldn’t be profitable.

Looking at scenario A-2, the small company can profit on its investment in a smaller, $1.6 million wellness center while still enjoying the same annual savings on insurance premiums over 10 years. In the 10th year, the IRR is 18.2%, while savings on premiums remains $5.5 million. NPV is $1.6 million, which is equal to the initial investment.

Bigger Firm, Similar Results

In scenario B-1, we’ve doubled the size of the company to 250 workers, and therefore the total annual payroll increases as well, to $25 million. The cost of the wellness center, however, is back to $3.2 million. (See Figure 3.)

Based on our analysis, we found that a larger company can profit on a sizable $3.2 million wellness investment, with the same small annual reduction in insurance premiums over 10 years. Because costs are spread over twice the number of employees, the 10th year IRR is 18.6%, and savings on premiums exceed $11.4 million. The investment’s NPV tops $3.35 million at this level, which slightly exceeds the cost of the wellness center.

In examining scenario B-2, you’ll see that a larger company can profit from a smaller $1.6 million wellness investment and pay less in medical insurance premiums over 10 years. Because the initial costs are 50% less, the IRR is 31.4%, yet savings on premiums remain more than $11.4 million. The investment’s NPV is nearly $5 million. (See Figure 4.)

An important feature to highlight is that, in all scenarios, the discounts on medical insurance premiums absorb the effect of inflation by year 8. Regardless of the size of the annual payroll or the initial amount invested in the wellness center, the models demonstrate that investing in wellness can be profitable in terms of dollars alone. This result is independent from the benefits of increased productivity, decreased sick days, and reduced absenteeism.

WHAT LIES AHEAD?

Healthcare costs are rising. Paying for healthcare can be a challenge for employers and employees alike. As companies strive to find ways to reduce costs, they are initiating comprehensive wellness programs to control rising healthcare insurance premiums.

But management has to take on the difficult task of moving high-risk employees into the program and keeping them enthusiastic about it. As we’ve shown in our analysis, financial returns can vary—and can be elusive unless the organization is capable of compelling participation and finding balance for its particular circumstances. In any case, a positive return is achievable, and that alone makes a strong case for investing in wellness programs. When companies factor in increased productivity and the benefit of attracting and retaining healthy employees, the decision looks even better.

Wellness programs must be considered part of a long-term strategy. Return on investment can occur, but not in the short term; it requires several years. Therefore, for companies that focus on short-term financial performance, wellness programs may not be a reasonable investment.

Finally, it’s important to restate that ROI isn’t the only way to measure the success of a wellness program. Wellness programs increase productivity, reduce absenteeism, and create a happier work environment. Financial incentives aside, we strongly believe that taking care of employees and encouraging wellness programs in our companies is the right and responsible thing to do.

December 2015