THE PROBLEM

One answer to why this student felt like a second-class citizen emerged from the Undergraduate Curriculum Committee, which in August 2012 was tasked with reexamining the accounting curriculum. Soon into the Committee’s deliberations, it became obvious that Penn State was underserving a majority of its accounting students. The school has a well-established and intensely selective master of accounting (MAcc) program that meets the 150-credit-hour requirement for the CPA (Certified Public Accountant) license in Pennsylvania. Offered in two formats, the MAcc program caters to only about a third of the annual graduating class because of capacity constraints. Students enrolled in the MAcc program benefit from the cohort effect, occupy a fast track to internships and jobs, and enjoy the privilege of national and regional public accounting firms frequently courting them. One measure of the MAcc program’s success at Penn State is that almost all students receive job offers before they graduate.

The situation isn’t as rosy for the remaining two-thirds of the accounting majors. Many bright, motivated, and technically sound students face an uphill battle in getting noticed by the public accounting firms competing for talent since they are focusing their attention on MAcc students.

Left largely to their own devices to obtain internships and job offers, many non-MAcc accounting majors have internalized the symbolic effects of the group to which they are assigned. The combination of envy and self-doubt that comes from being classified in a lesser status can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The profession’s intention to raise the barriers to entry by requiring 150 hours of classroom instruction has worked only too well. It has encouraged the existence of two classes of accounting majors at Penn State—MAcc students and everyone else—which fuels the sentiment of being second-class. But is this a necessary outcome? Must accounting programs discriminate between those tagged for careers in public accounting and those swimming upstream trying to get in?

Conversations with recruiters and alumni from the private sector provided a sharper image of why they were fishing for talent in finance and not accounting waters. Spurred on by the increasing importance of risk management, internal controls, and strategic cost management, global manufacturers like PPG Industries, niche consulting firms like MorganFranklin Consulting, and Wall Street firms like Goldman Sachs were a few of the many companies that expressed a strong interest in hiring accounting majors. Yet they felt they couldn’t compete effectively for that talent. More than one corporate recruiter spoke of accounting majors who had received internships but then went for opportunities in public accounting when it came time to seek full-time employment.

Accounting students identified accounting with public accounting so much that they didn’t know that many accounting careers weren’t geared to audit and tax work and that an accountant doesn’t have to be a CPA. Moreover, instead of rigorously evaluating all possible career paths, many accounting students believe that starting in public accounting is an indispensable stepping stone. They are unaware that thousands of accountants in corporate America have rewarding careers in private industry without having worked in public accounting first.

Perhaps it was the historical dominance of public accounting in accounting programs that explained the lack of awareness and misperception of students about the possibilities of and pent-up demand for accounting graduates outside the confines of tax and audit work in public accounting firms. Yet further investigation of hiring needs among the Big 4 and regional public accounting firms that recruit heavily at Penn State suggested otherwise. Advisory and related consulting services are a growth sector in the public accounting industry. The profession has begun to hire from diverse majors, including information sciences, sociology, and health administration.

While still important, audit and tax services under the aegis of a CPA license are no longer a necessity for a career in even a public accounting firm. Global firms like Ernst & Young and Deloitte and smaller ones like Aronson LLC and Baker Tilly have repeatedly affirmed their need for non-CPA accounting graduates. Indeed, it was PricewaterhouseCoopers that funded the nascent efforts to define and establish the Corporate Control and Analysis Program at Penn State aimed at such nontraditional but emerging accounting careers.

THE SOLUTION

This analysis of the potential market for accounting majors revealed a white space for curricular innovations. Both the corporate sector and the accounting profession wanted to hire accounting majors who weren’t keen on auditing and tax. Not all accounting students were aware of such opportunities, and, even if they were, they thought it was less financially rewarding than the usual CPA-bound career. Many didn’t know that most accounting graduates who start their careers in public accounting move to industry within three to five years and that the overwhelming majority of accountants work outside that profession.

Thus the fault lay with the program structure at Penn State. Not enough attention had been devoted to informing students about non-CPA-track accounting career opportunities. At Penn State, and presumably in many other accounting programs across the country, there isn’t a well-developed career pathway for accounting majors whose interests lie outside being CPA-licensed tax and audit practitioners.

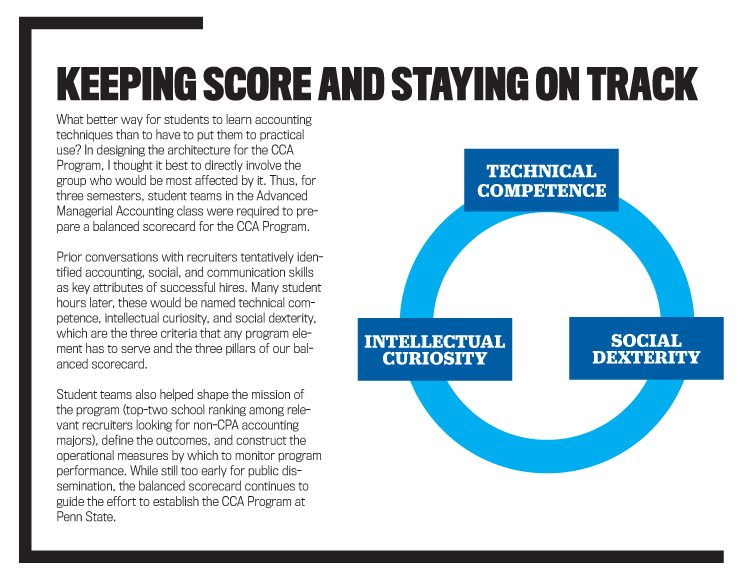

The Corporate Control and Analysis Certificate Program is such a pathway. It generates a supply of interested and capable candidates to meet the demand from industry and from advisory and consulting services for accounting graduates. A relatively systematic examination of peer institutions didn’t suggest many models we could emulate. Consequently, we engaged in a balanced scorecard exercise spanning three semesters to help define the mission, competing interests, and process elements needed for success. An academic program’s success hinges on the mutual satisfaction of employers and potential employees.

Designing the CCA as a certificate program, which is officially recognized on student transcripts, not only signals the suitability of its graduates to the corporate finance/accounting, advisory, and consulting job markets but also affirms their distinctive academic preparation. Also, requiring the program to not exceed the standard four-year credit load of 120 hours complies with internal administrative demands and avoids adding to the overall educational costs of a college degree, a matter of some importance in the age of exploding student debt.

Most significantly, using the balanced scorecard exercise allowed us to identify three pillars of excellence that would serve as guideposts for execution. We selected every program element and continue to select each one if and only if it serves to improve the accounting skills of students (technical competence pillar), nourish their spirit of inquiry (intellectual curiosity pillar), or enhance their capacity to deal with others (social dexterity pillar). (See “Keeping Score and Staying on Track” on page 35.)

Technical Competence

The CCA Program at Penn State builds on the already excellent academic coursework demanded of all accounting majors. After mapping the content of the CMA® (Certified Management Accountant) exam to the curriculum, we introduced subtle modifications to the list of required courses and continue to engage in a judicious alteration of the content of specific courses. These changes have allowed us to peg the CMA exam to the base of the required CCA coursework. Accordingly, the motivated CCA candidate could graduate having passed both parts of the CMA exam in addition to having earned the CCA certificate and the bachelor of science degree in accounting. In addition, all CCA graduates must obtain an approved internship, which is intended to help clarify their career choices. Finally, we strongly encourage CCA candidates to complete a series of online training modules in Excel-based financial modeling, quantitative data analysis, and mathematics for business. Through these measures, the CCA graduate should be able to convincingly prove his or her technical competence to interested employers.

Intellectual Curiosity

There has been much talk about the challenges of teaching Millennials. A number of recruiters spoke of the need to inculcate in students the benefits of going beyond the narrow specifications of what is explicitly stated or required. All too often, accounting instruction reinforces the habit of procedural thinking—of seeking and executing step-by-step directions to obtain correct answers. This algorithmic thinking is slated for obsolescence by computers.

To nourish in students the spirit of constant inquiry and lifelong learning to deal with the fast-paced changes of contemporary business, the program relies on the CCA Student Club and related IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) student chapter to expose CCA candidates to a broad menu of activities. Club members participate in IMA-based case competitions, prepare industry and company biographies, build bibliographies on emerging trends and topics, go on field visits to factories and offices, and attend seminars conducted by professionals on a wide range of topics.

Social Dexterity

Accounting graduates can establish the foundations for good judgment by cultivating curiosity and develop the ability of sound analysis by honing their technical competence, but that isn’t enough. Social dexterity is equally important to being effective communicators and leaders.

Consider a seemingly trivial example. I still recall my confusion and discomfort some years ago when I was on a conference call for the first time with a group of human resources personnel from Verizon. There were long pauses, and people were speaking over each other, entirely because I wasn’t prepared for the protocols of conference calling. Repeated practice can teach such skills, which students should be exposed to before they enter the workplace. To this end, the CCA Program includes a required semester-long course in presentation and communication skills.

Additionally, the CCA Student Club organizes events for CCA candidates to meet and interact with working professionals, engage in teaming exercises, participate in dinners that teach etiquette, and learn the best practices for making conference calls effectively and using social media. Moreover, given the many international students enrolled in the accounting program at Penn State, the Club has begun to think of ways it can foster cross-cultural knowledge and sensitivities.

In these ways, the CCA Program develops in students the professional and personable comportment in attire, speech, and manners that’s crucial to successful careers in accounting.

PAY ATTENTION TO DETAILS

The best-laid plans can go awry if they aren’t well-executed. Crafting a vision is relatively easy compared to the sustained attention to myriad details that’s required when implementing a plan. Faculty members usually aren’t versed in management. Trained to research and teach, which are largely solo activities, they’re typically unprepared to manage, identify the interests of different constituencies, balance competing interests, and bargain and trade for what is feasible instead of dogmatically holding onto what is ideal. Perhaps it’s good for faculty to step into a management role. The experience can be useful in enlivening what they have learned from books with a dose of realism.

Two elements are crucial to the success of a new academic program. First, the objective or mission must be well-defined. Once the mission is shaped by inputs from different constituencies, such as recruiters and students, the program must have a clearly specified objective. In the inevitable negotiations that stress-test every detail of the proposed program, you’ll be asked to modify or even give up one or the other of what was planned. A clearly specified objective prevents the loss of your main objective.

The second element crucial to success is to identify and, where possible, partner with every group directly and indirectly affected by the program. In a large university such as Penn State, there are many groups, each with its own interests and agendas. Though “failure is not an option” is a useful attitude to have when trying to introduce change, “learning from one’s mistakes” is an even better adage to follow in such circumstances.

It takes time and effort to learn what other affected parties want and to see your program from their perspective. You shouldn’t ignore these constituencies since, like most things, a new program is a collective endeavor that relies on all participants. The humility needed to listen also allows you to engage constructively with others, which often causes them to want to contribute to your success.

CHALLENGES AND LESSONS

About four years will have elapsed since the first proposal for the program was conceived until the first CCA class (selected seniors who start the CCA Program this month) graduates in May 2016. All too often, the relatively slow and repetitive cycles of proposals and approvals going through numerous committees can be frustrating and even make us want to give up on the project. To justify impatience, some people may trot out the usual suspects—red tape, turf protectors, and empire builders. No organization, and certainly no large organization, moves at the speed we’d all like. For all the talk of agile corporations, there is at least one good reason that organizational change embodies that old Latin proverb, “make haste, slowly,” so well. As the former controller of Bayer Corporation once told me, “The reason organizations sometimes move cautiously is because a mistake can cost millions of dollars.”

A new academic program diverts resources from other uses, establishes new fixed costs, and, perhaps most important, requires people to change settled ways of thinking. New perceptions and expectations take time to form and displace old ways of thinking. Questions and concerns sprout up all the way up and down the organization. Does the introduction of a certificate program hasten the university toward being a certificate mill? Does establishing a CCA Program further fracture the accounting program into even more finely discriminating classes? Does the use of the phrase “financial management” misassign to accounting what properly belongs to finance? Such questions require time to weigh and resolve. It’s better to assume that counterparties bear no malice or ill will when they pose hard questions. Such an assumption forces us to have the patience and perseverance needed to induce well-thought-out changes in organizational practices.

Yet no amount of fair hearings and dogged commitment can make a project succeed without the help of others within the organization. First is tone at the top. The energetic support of academic leaders, typically the heads of departments, plays a vital role. Effective leaders clearly articulate the long-term strategic vision, step in when necessary to solve a problem, and continuously maintain the pressure to move forward. Only under such a protective aegis can new initiatives take root.

No less critical is the administrative staff’s institutional knowledge. These staff members help identify past efforts that have succeeded or failed as well as necessary administrative procedures. They even offer a deep read into the minds of the student body. In every university, there are divisions devoted to career services, academic club activities, student development, and curriculum design. Partnering with these segments is crucial to setting up a new program on a strong foundation.

Yet all facilitators haven’t been university personnel. Three constituencies outside the university have been equally vital to establishing the CCA Program at Penn State—recruiters, alumni, and IMA. Informal and formal surveys among recruiters not only confirmed their interest in a CCA-type accounting graduate but also helped refine the curriculum. Getting them to speak about internships and jobs through frequent campus visits was vital to start the process of informing and convincing accounting students of the range of career opportunities available.

Penn State boasts committed alumni who represent a staggeringly broad swath of industries. It’s both encouraging and gratifying to see how quickly alumni are willing to serve as champions of a cause they believe in, whether this takes the form of campus visits, identifying funding opportunities, or opening avenues to increase internships and job offers to the students.

IMA has been central to raising the CCA Program’s credibility. For those who pass the CMA exam and fulfill the criteria, the globally recognized CMA certification constitutes an independent attestation of the technical competence of the CCA graduate. The advantage of a student being able to sit for and pass the exam by the time of graduation sends a powerful message to the employer. IMA also helped set up a student chapter, provides discounts on exam fees and memberships, and holds a highly regarded annual Student Leadership Conference that Penn State students have begun to attend regularly.

Perhaps most useful to raising students’ awareness about accounting careers in industry, IMA representatives have visited the campus on numerous occasions. From chapter presidents to the director of educational partnerships, many IMA leaders have made the trek to inform, educate, and persuade potential CCA candidates. There was a time when Penn State had the highest number of CMA exam passers. Attaining that distinction again would be one measure of the CCA Program’s success.

But the proof of the pudding lies in the eating of it. Certificate programs, the CMA exams, Excel training, and conference call practice aren’t worth much if students don’t find rewarding careers. All the support and encouragement from partners inside and outside the university will have been wasted if recruiters from industry, advisory, and consulting don’t consider the CCA Program a preferred hiring source. The measureable mission of the CCA Program at Penn State is to rank among the top two schools by relevant recruiters and to have 98% of its graduates obtain job offers before they graduate. These measures don’t fully reveal what the program is really about. When we reach these goals, far fewer accounting students will feel that they are second-class. The CCA Program at Penn State is devoted to that unwavering promise.

August 2015