In growing companies, especially multinational corporations, there can be hundreds of thousands of internal transactions involving different currencies and tax treatments, often with much of it recorded only on spreadsheets. If accountants handle these internal transactions incorrectly, any out-of-balance accounts that impact the financial statements can introduce compliance issues.

Tackling this enormous task requires a thorough understanding of the processes involved in intercompany transaction reconciliation, elimination, and settlement as they are generally performed within many multinational organizations.

UNDERSTANDING INTERCOMPANY TRANSACTIONS

An intercompany transaction occurs when one division, department, or unit within an organization participates in a transaction with another division, department, or unit in the same organization. These transactions might involve a parent company and a subsidiary, two or more subsidiaries, or even two or more departments within one unit. And they can occur for a variety of reasons. For instance, a company may sell inventory from one division to another division, or a parent company may loan money to one of its subsidiaries.

Each transaction has nuances to consider. For instance, if the transaction occurs between the parent company and a subsidiary, accountants must treat it as an arm’s length transaction where the two parties act independently as if they have no relationship to each other. Both the parent company and the subsidiary must record it. At the consolidated level, accountants must eliminate the intercompany transaction so that no profit or loss is recognized until it’s realized through a transaction with an outside party.

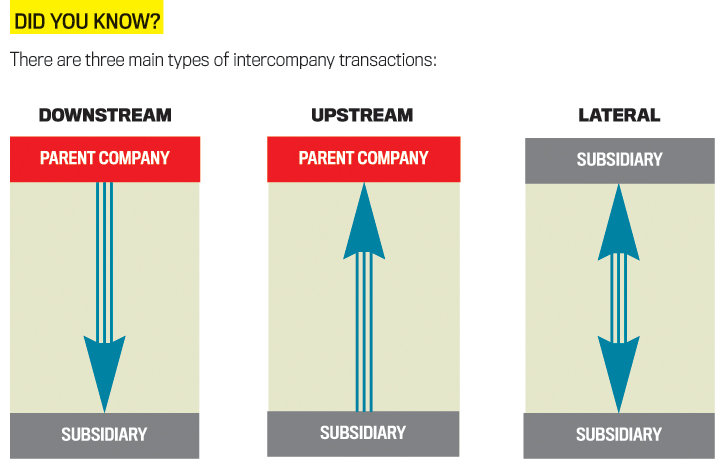

There are three main types of intercompany transactions: downstream transactions, upstream transactions, and lateral transactions. It’s important to understand how each of these is recorded in the respective unit’s books, the impact of the transaction, and how to adjust the consolidated financials.

A downstream transaction flows from the parent company to a subsidiary. In this type of transaction, the parent company records the transaction and applicable profit or loss. The transaction is transparent or visible only to the parent company and its stakeholders, not to the subsidiaries. An example of a downstream transaction is the parent company selling an asset or inventory to a subsidiary.

An upstream transaction flows from the subsidiary to the parent entity. In an upstream transaction, the subsidiary records the transaction and related profit or loss. For example, a subsidiary might transfer an executive to the parent company for a period of time, charging the parent by the hour for the executive’s services. In this case, majority and minority interest stakeholders can share the profit or loss because they share ownership of the subsidiary.

A lateral transaction occurs between two subsidiaries within the same organization. The subsidiary or subsidiaries record a lateral transaction along with the profit or loss, which is similar to accounting for an upstream transaction. An example is when one subsidiary provides information technology (IT) services to another subsidiary for a fee.

When determining how accountants must adjust the consolidated financial statements, it’s critical to understand how intercompany transactions are recognized initially and their impact to the income statement and balance sheet. The adjustment process is extremely time-consuming and prone to human error, particularly if it involves a blizzard of spreadsheets.

The process is further complicated when only some of the entities are wholly owned or if the company employs different general ledger systems, uses multiple currencies, and is subject to diverse tax implications like a value-added tax (VAT). Another problem is that many organizations lack standardized processes and internal governance rules stipulating who can and can’t conduct intercompany transactions.

Here’s an all-too-common scenario. A subsidiary in Germany enters into a transaction with a subsidiary in the United States. The entity in Germany records the transaction in euros, while the entity in America records the transaction in dollars. This results in an out-of-balance intercompany transaction with potential tax complications. If the entities use different enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, validating the journal entries is complicated by the systems’ different characteristics. If the accounting staff books the entries in different months—for example, if they book one journal entry on March 30 and the other on April 2—an automatic imbalance will occur. This is further complicated by the different currency exchange rates each day.

Obviously, the previous scenario poses enormous complications and risk for finance and accounting teams in preparing the consolidated tax return or financial statement. Just getting the two entities to agree about the cost of the transaction, the currency translations, and possible VAT treatments is an uphill climb. It’s no surprise that reconciling and settling intercompany transactions is the bane of accountants everywhere.

MASTERING INTRICATE ELIMINATIONS

The intercompany eliminations process entails removing any transactions between the entities within a company from the financial statements—in other words, eliminating the effects of intercompany transactions. Generally, there are three types of intercompany eliminations: elimination of intercompany revenue and expenses, elimination of intercompany stock ownership, and elimination of intercompany debt.

Intercompany revenues and expenses are transactions that involve the sale or cost of goods sold to affiliated companies as well as the interest expense to and from affiliated companies. The accounting staff eliminates these transactions because they represent the transfer of assets from one associated entity to another. The reason is clear: A company can’t recognize revenue from the sale of items to itself. Eliminating the related revenue, cost of goods sold, and profits results in no effect on the company’s consolidated net assets.

Elimination of intercompany stock ownership, on the other hand, eliminates the assets and shareholders’ equity accounts for the parent company’s ownership of the subsidiaries. For example, if a parent company has unrealized intercompany profit included in its retained earnings at a particular period end, the noncontrolling interest is misstated. The accounting staff must prepare an intercompany elimination to remove the intercompany profit that was included in retained earnings.

An elimination of intercompany debt is needed when the parent company makes a loan to a subsidiary and each party respectively possesses a note receivable and a note payable. When consolidating the two entities, the loan becomes nothing more than an exchange of cash. Consequently, staff must eliminate both the note receivable and the note payable.

Performing the different types of intercompany eliminations can be quite complicated because it involves a great deal of reporting and paperwork. Yet these tasks are critical to the financial information’s integrity.

CONQUERING COMPLEX SETTLEMENTS

An equally complex, challenging, and time-consuming process is settling intercompany transactions. It often makes it difficult for companies to meet their month-end close deadlines.

Settling intercompany transactions involves manual, labor-intensive activities. The different entities involved must come to an agreement on the information related to their respective transactions. Using the example of the German entity recording a transaction in euros and the U.S. entity recording the same transaction in dollars, both parties ultimately must agree on an amount and correct any discrepancy that exists. Once again, the burden of resolving these discrepancies typically falls on the corporate accounting team, which has to work with the different units to reach a solution.

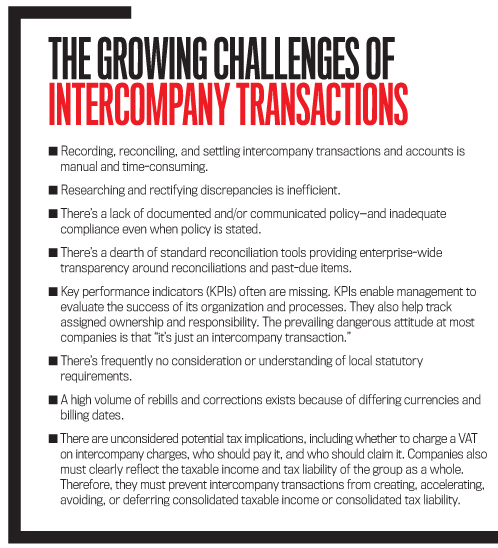

From a compliance standpoint, the intercompany transaction process is becoming increasingly burdensome and risky for globally expanding companies. See “The Growing Challenges of Intercompany Transactions” for a checklist of difficulties that must be corrected.

The ability to resolve these various challenges also is compromised by time pressures. It’s difficult for management and auditors to reconcile and resolve the great volume of intercompany transactions within an acceptable time frame. Accountants trying to resolve open items may delay the month-end close. Certain open items may carry forward to the following month. If compounded, it can lead to large, unreconciled amounts.

A SOLUTION IN AUTOMATION

There are several financial consolidation and reporting systems available today that help with the intercompany reconciliation and elimination process. But most address only the elimination component, still saddling accountants with the reconciliation piece of the process. Others only address the reconciliation process or assist workflow challenges. The most comprehensive solution is one that provides:- Simple, standardized end-to-end intercompany accounting process documentation;

- A visible repository for all end-of-month statements, such as SharePoint or some other content management repository;

- An automated reconciliation tool with exception reporting;

- Shared KPIs for all the accountable parties;

- Global contact listings of accountable parties by entity;

- A formalized escalation process to alert appropriate management about problems;

- Global imbalance and aging reports;

- Legal/tax restriction policy on deviations;

- Realistic materiality thresholds; and

- A single monthly cutoff date for all billings, such as one week before the month-end closing.

Such a best-of-breed solution should centrally interface with all of a company’s core ERP and legacy systems in real time. It should also include a single process for collecting and distributing intercompany transactional data, eliminating any issues over currency values, transaction amounts, and tax implications.

There’s tremendous value in automating the complex and time-consuming processes involved in reconciling, eliminating, and settling intercompany transactions. It relieves the burdens imposed on company accountants, mitigates the risk of human error, and decreases the threat of an accounting mishap. In this era of modern finance, companies have a responsibility to automate now.

SF SAYS

When determining how to adjust the consolidated financial statements, it’s critical to understand:- How intercompany transactions are recognized initially,

- Their impact to the income statement and balance sheet, and

- That the process is extremely time-consuming and prone to human error when many spreadsheets are involved.

April 2015