Management accountants are increasingly tasked with developing innovative solutions to time-sensitive business problems. Prompted by the dynamic environment within which many organizations find themselves, the rise in demand for an efficient path to business solutions translates into accounting and finance teams acquiring new skills to implement novel approaches to problem solving. One such method they can use is creative problem solving (also known in this context as CPS).

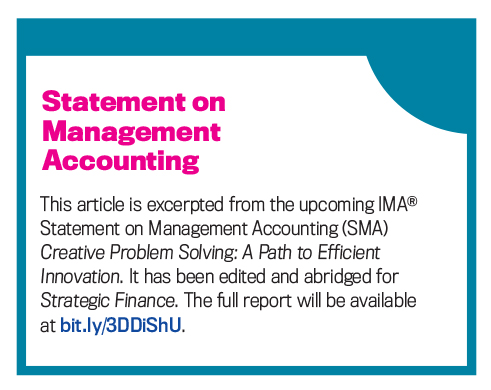

CPS offers a four-step process that leads to novel solutions and enables management accountants to optimize creative thinking to find solutions in a matter of a few hours. The methodology provides an efficient and effective framework for companies to tackle a single challenge by taking teams through four problem-solving steps (see Figure 1):

1. Clarifying a challenge

2. Ideating solutions

3. Developing a proposed solution

4. Planning for implementation

The CPS process requires teams to look at a problem from many different perspectives and to brainstorm numerous options before selecting the best solution. CPS empowers accountants to generate ideas in an inclusive and efficient way that can strengthen their contribution to strategic decision making, enabling delivery of incremental value to their organizations.

Employing the CPS process can position management accountants to make even greater contributions to organizational performance and competitive advantage during the most critical times. By understanding the four steps of CPS, accounting and finance teams can work together in new ways, allowing for increased collaboration and innovative thinking.

WHEN TO USE CPS

CPS is most effective when tackling a challenge that requires innovative thinking for questions such as “How might we improve a process?” or “How might we reduce costs?” The following real-world examples show how CPS has helped organizations in the business and nonprofit sectors.

General Motors used CPS at a plant in upstate New York to reduce manufacturing costs. During a CPS training session at the plant, the operations team wanted to tackle the problem of ring gears (which are critical components in manufacturing) sticking in the dies (which are cast or mold-like tools that enable manipulation of a material into a specific shape and size) and breaking during the manufacturing process. During the brainstorming session, one of the team members suggested spraying something like a nonstick cooking spray on the dies before casting. Another team member suggested using a spray bottle (cost $1) with a nonstick solution ($0.50) to apply the solution on ring gears before production to prevent sticking. Plant operators now spray the dies before making ring gears. Thus, within a CPS session of 45 minutes, a solution was developed that saves the plant $40,000 per week.

Another example is the Small Business Development Center (SBDC) at Youngstown State University. The SBDC had both limited funding and staff and therefore needed to narrow its strategic priorities to what could be accomplished in the next six months. The director decided a collective effort would be better than any plan she might create independently, so she decided to hold a CPS session with her staff. The session focused on setting priorities and brainstorming the tasks needed for completion in the immediate future.

As a group, the team decided to redesign the SBDC’s service offerings to both showcase its strengths and maximize benefits for the local economy. Staff brainstormed ideas for: How might we find time to do this? How might we develop content? How might we select the services that would have the greatest impact? After a three-hour session, the director was satisfied with the ideas generated, and the group developed a six-month implementation plan with deadlines and personnel assignments. The team also delegated responsibility to different staff members who would oversee the plan to ensure it was being implemented as intended.

At West Los Angeles College, the college president asked a faculty member to write a proposal to convert a 2,000-square-foot multipurpose space into a Creativity Studies Lab. The faculty member, also the future director, wanted to write a persuasive grant proposal. She assembled a CPS team to help her improve the proposal.

The team brainstormed suggestions recommending ideas such as discussing stakeholder value, calculating return on investment, and adding the use of a flex space to the report. The group also helped her identify “assisters,” those who would serve as her allies, and “resisters,” those from whom she should try to garner support. After the two-hour session and asking various individuals to read her draft, the faculty member submitted her proposal for the new Creativity Studies Lab and received a seed grant to fund its creation.

Consistent with these examples, management accountants can use CPS for similar challenges such as brainstorming strategic perspectives, setting priorities, or preparing business cases. The beauty of CPS is its simplicity if a creative solution is needed in less than a day.

Not all problems require CPS: Some problems have obvious solutions, such as booking an accrual to recognize revenue for a sales transaction that has already occurred but for which cash will be received in the future. CPS, however, should be used by a person who needs a creative solution and has the authority to bring about change.

BEFORE THE CPS SESSION

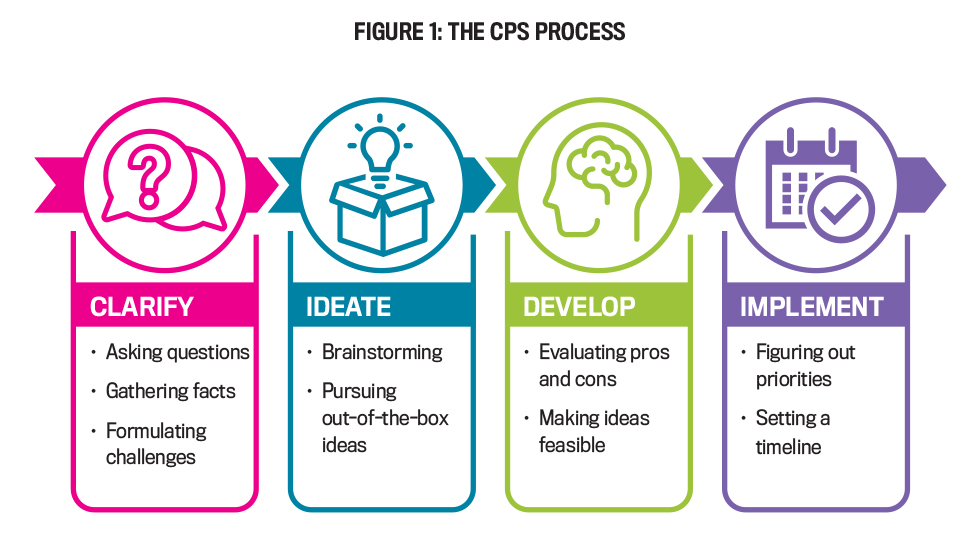

To hold effective CPS sessions, preparation is necessary. Ismet Mamnoon, a CPS consultant and former accountant, says, “For creative methodologies to be effective, certain preliminary steps should be followed to support an optimal experience.” The principles of CPS are based on the flow of ideas from nurturing a creative environment that allows for humor, mutual respect, reflection, excitement, idea incubation, and effort, and providing a stage that allows for the use of sticky notes and permanent markers or a virtual whiteboard. There are six essential prerequisites to beginning the CPS session to increase the likelihood of success (see Figure 2).

Assemble the CPS team. Ideally, a team includes the client, a facilitator, the resource group, and a process buddy. The facilitator, an expert in CPS, guides the process. The client is the person who owns the challenge. The resource group—usually three to seven people—are those who can add energy, enthusiasm, and relevant knowledge to the process by generating and evaluating ideas. Finally, a process buddy is an assistant who helps the facilitator manage the logistics and tasks during the session, freeing the facilitator to focus on leading the group through the four steps in the CPS process.

Secure adequate meeting space. The meeting space for the CPS session can be physical or digital. Physical creative thinking environments provide whiteboards and flip charts in a room with enough space for participants to stand and move around. In the digital world, companies provide online whiteboards that operate similarly to a physical space, where participants can type on sticky notes and arrange them in a digital platform.

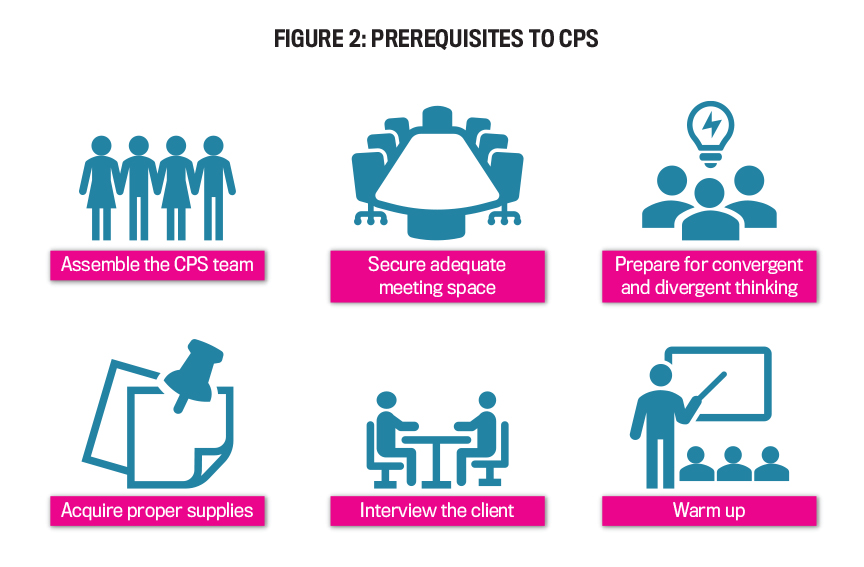

Prepare for divergent and convergent thinking. Each step in CPS includes the movement between divergent thinking (generative thinking) and convergent thinking (evaluative thinking), as first identified by Alex Osborn, the father of brainstorming. Without this movement, the process can’t move forward. For example, during a brainstorming session, participants present many ideas to address a challenge—divergence—and then cluster those ideas and decide which one should be developed—convergence. The guidelines for divergent and convergent thinking are presented in Figure 3, which should be posted in the room prior to the session for the team to see and review during the process.

Acquire proper supplies. The proper supplies for a meeting in a physical space include sticky notes (like Post-it notes), small paper sticky dots of different colors, and markers. A few tips of the trade include:

- Consider the use of 3" x 5" sticky notes, as typical 3" x 3" sticky notes might be too small.

- Encourage participants to use markers rather than ink pens to write on the notes so that all participants can read what is written.

- For added creativity and engagement, some facilitators bring toys, such as Legos, interlocking plastic bricks, or stress balls, for participants to fiddle with and snacks for breaks.

Interview the client. Prior to the CPS session, the facilitator meets with the client to explain the process, agenda, and support needed, and to confirm that CPS is the appropriate methodology to address the client’s challenge. This session takes about an hour to complete and is usually conducted a few days ahead of the CPS session.

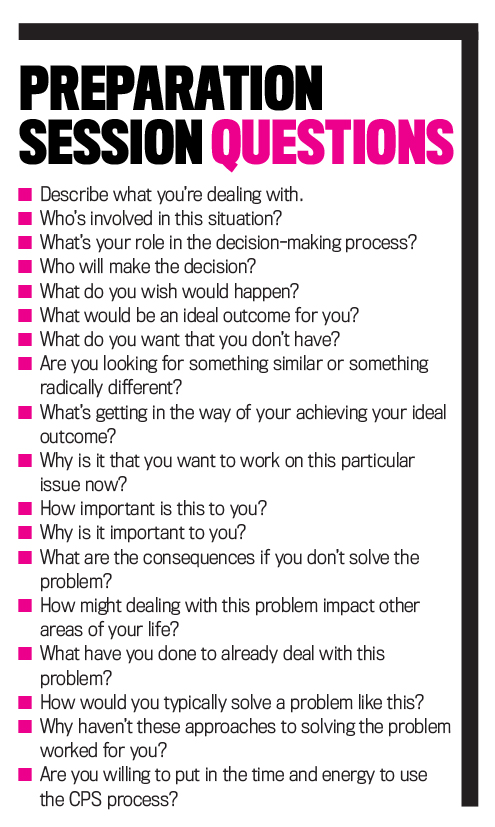

In the preparation session, the facilitator will interview the client to clarify the challenge, posing a series of probing questions (see “Preparation Session Questions”). The facilitator will record responses as the client speaks to aid in freeing up the client’s mind to gain new perspectives about the challenge.

After recording the answers, the facilitator will ask the client to highlight the answers that best speak to the challenge, present new insights, or are important to consider for a CPS session. Then, the facilitator will ask the client to put a check mark by the statements they have influence over. Next, the client is asked to put a check mark after statements that require imagination. Lastly, they’re asked to put a check mark by statements that need immediate attention.

After reviewing what appear to be the most important statements, the facilitator will ask the client to complete the following visionary statements:

- I wish…

- It would be great if…

- Wouldn’t it be nice if…?

The facilitator asks the client which visionary statement they would like to present to the resource group, then makes a poster that lists the visionary statement and key data points to take to the CPS session.

Warm up. Like physical exercise, a warm-up is best to ready the brain for creative thinking. Warm-ups should be used at the beginning of any session or after a long break, such as lunch. Another goal of a warm-up is to loosen people up, adding the “silly” factor. Facilitators can use a simple exercise such as “What might be all the uses for a brick—be as creative as possible?” or “How might we improve an airplane seat?”

The goal of this warm-up exercise is for the group to come up with 30 to 50 ideas in a few minutes. If the group slows down, the facilitator can use a technique called forced connections, which asks an additional question to the original one to prompt more ideas. For example, the facilitator could ask the group, “If you were an animal, how would you use a brick?” or “If you were a child, what would you like to add to an airplane seat?” Using forced connections teaches participants to view challenges from different perspectives, thereby leading to increased ideation.

Facilitators should encourage the group by saying, “You’re doing well. I like these ideas. Keep them coming!” Be wary about praising certain types of ideas or specific individuals as it might send a message to the group that the facilitator is looking for certain types of ideas or is encouraging ideas from certain individuals.

THE CPS SESSION

As a session begins, the facilitator presents the agenda. The facilitator will also share the guidelines for divergent and convergent thinking. These rules should be restated each time the group uses divergent and convergent thinking.

Each step in the CPS process—clarify, ideate, develop, and implement—is critical to leveraging the methodology effectively. Following the key activities in each will contribute to the efficient development of tailored solutions.

Step 1: Clarify. At the session’s onset, background information—the organization’s industry, culture, and disruptions—is shared with the resource group. The key data points on the poster created at the client interview will be read by the client to the team, with the team asking questions. The client’s “I wish” statement will also be shared.

In the CPS process, step 1 typically takes the most time. After introductory remarks and a warm-up exercise, the team will help the client clarify the challenge by reframing it into a problem statement. Using phrasing such as “How to…” or “How might…” is key to advance to step 2. Participants should be encouraged to write their ideas on sticky notes and place them on a whiteboard or flip chart. Examples of problem statements used by accounting and finance teams include:

- How might we set strategic priorities for the finance function that most effectively deliver value to the operational teams supported?

- How might we grant real-time access to our financial data that meets the needs of our business partners?

- In what ways might we measure the most relevant sustainable business information to our business?

- What might be all the ways we can streamline our procurement operations for efficiency and cost-effectiveness?

After coming up with 20 to 25 problem statements, the group can mark the statements that interest them the most, clustering similar statements together and ultimately naming clusters with new problem statements by theme.

Step 2: Ideate. In step 2, the team generates ideas and converges on a solution. One of the most common ideation techniques is brainstorming. Without proper training, however, the ideas generated at most brainstorming sessions aren’t unique but rather represent a collection of ideas already in participants’ heads. In many instances, people can’t seem to get to new ideas until existing ideas are out of the way. Research shows that it takes a few rounds of brainstorming for the best ideas to emerge (Paul Paulus, Jubilee Dickson, Runa M. Korde, Ravit Cohen-Meitar, and Abraham Carmeli, “Getting the Most out of Brainstorming Groups,” in Arthur Markman, ed., Open Innovation, 2016).

The two most common ideation techniques in CPS are “stick ’em up brainstorming” and “brainwriting.” Facilitators should consider using both to give extroverts and introverts a chance to ideate in a way that speaks to their preferences.

As the name suggests, stick ’em up brainstorming involves the team generating ideas, writing them on sticky notes, and posting the notes on a whiteboard. When team members say what they write, others can hear the idea so they don’t duplicate it, and that idea can spark new thinking. The order of sharing an idea is “write it, say it, and stick ’em up.” When working in a group, following a different order can be distracting, and some team members may not speak at all. Thus, at times, the facilitator may need to remind team members to follow the guidelines. If the group slows down when it comes to ideation, the facilitator can use techniques, such as forced connections, or can show pictures—nature, people, or food—and ask the group what new ideas they get from looking at the pictures. Another useful technique is role-playing, during which team members can take on roles of fraudster, CFO, auditor, government official, or even a superhero to spur ideation.

The other ideation technique is brainwriting, which is done in silence. This should be done after stick ’em up brainstorming, not before. Each member is given a brainwriting sheet containing nine squares with a sticky note placed in each square with an idea on it (see Figure 4). Each person writes three ideas on the brainwriting sheet. When completed, the team members pass their brainwriting sheets to someone else. This way, people can think of new ideas in silence by reading others’ ideas and building on them.

There are four key steps in the brainwriting process, which should be read out loud to team members before brainwriting begins:

- Participants write the problem statement/creative question at the top of each grid.

- They use the guidelines for generating ideas: defer judgment, strive for quantity, seek wild and unusual ideas, and combine and build on other ideas.

- Participants write three ideas on the first open row of the brainwriting grid—one idea per sticky note placed in each box.

- After writing three ideas, participants place the form in the middle of the table and pick up a different grid that another participant has started. If there are none, they start with another blank grid. With extras in the middle, no one has to wait for other members of the group. A grid will always be waiting for them.

After using both ideation techniques for around 20 minutes each, the facilitator should see if the client is satisfied with the quantity and quality of ideas. If so, then it’s time for the group to converge on the best ideas. The facilitator will give each team member three to five dots to place on the most promising or intriguing ideas. The group should consider the need for novelty when converging on the best ideas, clustering similar ideas together and labeling them, using a verb in the label.

For example, the problem statement for an accounting class was “How might we engage students to learn without thinking about grades?” After generating 75 ideas, the resource group (made up of students) labeled clusters with statements such as:

- Relate accounting to superpowers.

- Create new types of class projects (i.e., video).

- Add play/competition with prizes to classes.

After renaming the clusters, the resource group and client will decide what ideas they want to pursue. At this time, the facilitator should check the client to see if the team is on the right track. If the client agrees, the facilitator will ask the client to complete the following statement and write it on the flip chart for the team to see: “What I see myself doing is…”

In the example of creating an “engaged” classroom, the client (a faculty member) developed a model of peer learning, constructed with the help of the resource group. She could see herself implementing this peer learning model of teaching in future classes, using ideas from the resource group.

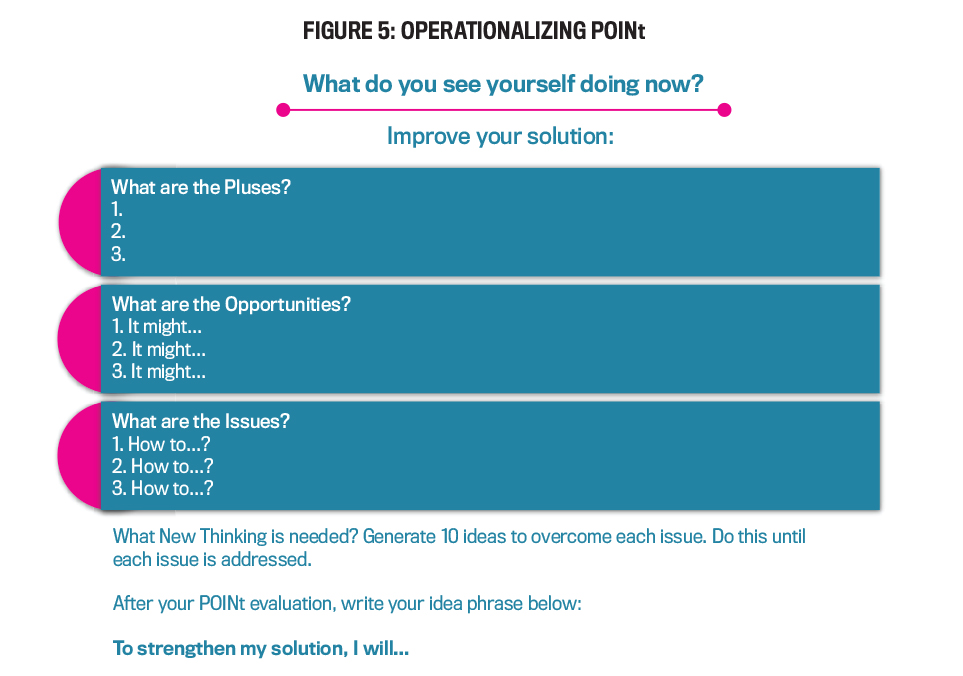

Step 3: Develop. Step 3 takes what the client envisions doing and turns promising ideas into workable solutions. This includes evaluating the pros and cons of the proposed solution with intentions of strengthening it by using techniques such as “assisters and resisters” or POINt (Pluses, Opportunities, Issues, and New Thinking).

“Assisters and resisters” ask questions to help the client strengthen their ideas. Assisters represent the people who might assist the client with the proposed solution, and resisters are those who might resist it. The team will create a list of stakeholders and categorize them as supporting or opposing the solution. The group will then brainstorm ideas for the following questions: How might we utilize or gain their support? How might we overcome resistance?

Bob Eckert, CPS consultant and CEO of New and Improved, said, “When a group is embedded in the creative process, and they want to move things forward, they are unstoppable. Resistance is welcomed as input to strengthen their efforts; assisting them wins you allies for your own future challenges.”

Similar to the assisters and resisters technique, POINt works to strengthen the proposed solution. The facilitator instructs the group to complete a POINt sheet (see Figure 5):

- List at least three pluses related to the promising idea.

- Next, list three opportunities (e.g., spin-offs, gains) for the idea.

- If the idea works, what are new opportunities? Use the statement “It might…”

- Finally, list the issues you have with the idea. Be sure each issue uses the wording “How to…?” These questions will allow the team to address the statement with new thinking to overcome any issues. For each issue, write 10 ideas to overcome each concern.

After completing that exercise, the facilitator should ask the team to converge, and the client will write a single statement on how to strengthen their solution: “To strengthen my solution, I will…”

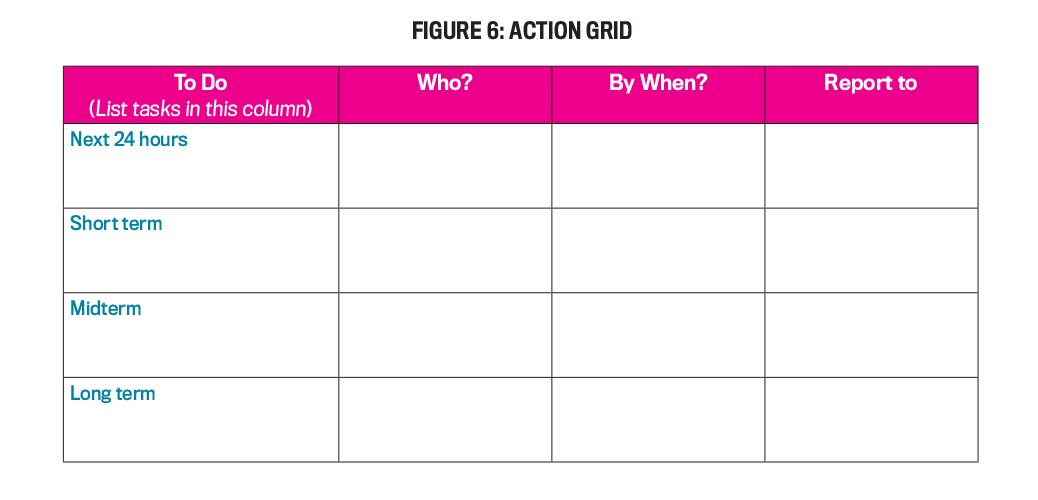

Step 4: Implement. In the final stage of the CPS process, the facilitator asks the client if they feel they have an effective, actionable solution to their challenge. If so, then the group will create an implementation plan, designed to fuel commitment by having the client commit to actions, dates, people, and accountability. Before filling out the action grid (see Figure 6), the facilitator will ask the team to generate at least 15 actions needed to bring the solution to reality and write them on sticky notes.

The action grid has columns for the specific action steps that need to take place: Who is going to do it? When will it be completed? Who will check to make sure it’s done?

The group also will use the action grid to place the tasks into the proper time frame: what needs to be done in the next 24 hours, in the short term (i.e., 30 days), midterm (31 to 90 days), and the long term (beyond 90 days).

The facilitator will ask the client if they’re satisfied with the action grid and the session. The client and resource group may feel tired after all the hard work, but they’re usually very satisfied with the plan they collectively developed to address the client’s challenge.

CREATIVELY DESIGNING TOMORROW

CPS can shift a group from focusing on obstacles to creating solutions. Key principles include balancing divergent and convergent thinking, reframing problems into questions, deferring judgment of ideas, building on each other’s ideas, and getting things done. While brainstorming, deferring judgment allows for potentially implausible ideas to turn into innovative ideas worth further exploration.

The CPS process can serve as a valuable strategic tool in the management accountant’s toolbox. No matter the role, developing proficiency in CPS equips professionals with an effective skill to foster creativity, leading to greater innovation for the finance function and business teams. Well beyond business professionals, CPS offers an efficient path to novel solutions to problems of nearly any type. Upskill today to tap into and develop your creativity.

March 2023