Audit fees for private companies averaged about $139,000, which is an increase of 5.6% over 2017. Some financial executives reported large increases in documentation requests as reasons for the increased time and expense to complete the audit.

The audit doesn’t need to be so expensive, disruptive, and intrusive to a business. Auditors bill clients based on hours worked, so facilitating a smooth audit will lower the number of hours worked and thus lower overall fees. If the average public company were able to lower its average fee by just 2%, it could save around $196,000. For private companies, the average number of hours to conduct audits were reported to be 1,395 at a rate of $191 per hour, which means a 5% decrease in audit hours could save the average private company more than $13,000.

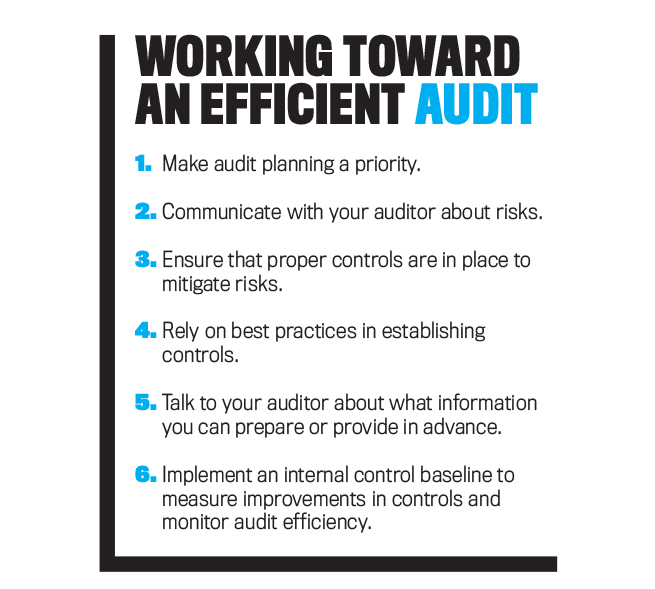

There are certain areas of a business that auditors consider to be material and high-risk and where they frequently spend a significant amount of time. Some steps that may help ensure an efficient audit include engaging with the auditor in planning the audit to make sure important areas are addressed, collaborating with the auditor about actions and controls to deal with risks, and establishing an internal control baseline to measure improvements in internal controls.

By conducting preparatory work in these areas, in addition to knowing how auditors determine materiality thresholds in areas such as revenue, accounts receivable, and inventory, you can help cut down on the length of the audit and thus reduce your costs. While some of these concepts will be familiar, they should serve as important reminders about how best to prepare for an external audit. A smooth experience could save your company money and reduce the time and frustration for you and your colleagues.

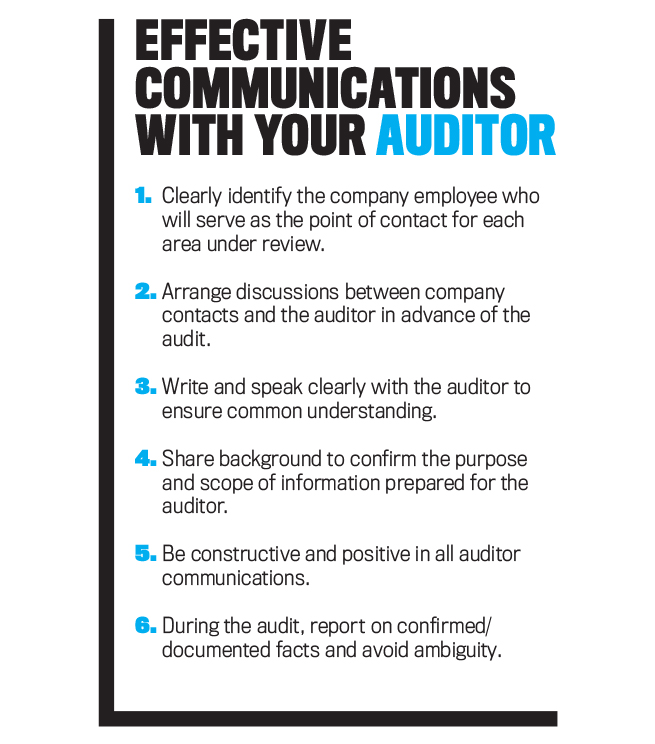

Generally, auditors will provide you with a requested list of items to prepare before they arrive. This list typically includes inquiries about areas of particular risk and transactions from which the auditors will pick a sample. Managers can help complete the audit process faster and with fewer questions by preparing responses to the items on the request list prior to or at the beginning of the audit. Additional time can be saved by communicating with the auditors ahead of time about significant changes in the organization, such as business acquisitions, new debts, new leases, accounting method changes, and new products and customers. These steps may facilitate the process and ensure that accounting implications are evaluated correctly the first time.

MATERIALITY

If you have a solid understanding of how the auditor determines materiality for your company, then you can identify and evaluate areas that are likely to be investigated. As such, you can ensure records and procedures in these areas are in good order.

Generally, a materiality threshold is set by choosing an appropriate benchmark, determining a level of this benchmark (often a percentage), and stating a justification for these choices. This process is prescribed and followed by regulatory bodies and auditors throughout the world. For example, a company’s pretax earnings amount is often used. Another alternative is to base this threshold on earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). Other commonly used benchmarks include gross profit, total assets, and total equity.

Establishing the precise measure will depend on a number of factors, such as industry, size, location, customer base, and whether the company’s financial reporting requirements are subject to oversight by a government agency, such as the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC). A private company where the primary user of the financial statements is a lender would be most influenced by EBITDA, as this most appropriately represents the amount of cash available to pay down the company’s debt.

It’s likely that a percentage of pretax earnings or EBITDA will be established as the appropriate measure of what auditors commonly refer to as “planning materiality,” which generally has an allowable range of 2% to 5%. In addition, you would want to get a sense of the tolerable error on the financial statement line items, which is the maximum error that the auditor is willing to accept. It’s set as a percentage of planning materiality and is based on whether the company is public or private as well as on the history of audit adjustments. A general range of tolerable error is 50% to 75%.

Auditors determine the tolerable misstatement based on the proportion of planning materiality. If the auditors perceive the risk to be high, the tolerable misstatement can range from 10% to 20% of the planning materiality. If they perceive the risk to be low, the tolerable misstatement can range from 70% to 90%.

Although auditors make an initial assessment of materiality based on the company’s forecasted EBITDA and tolerable error, materiality may be reassessed depending on actual financial results for the year. The following factors are taken into consideration:

- Conditions pertaining to the company and/or the surrounding control environment that may cause the auditors to believe that a decrease in materiality level would detect further differences.

- The presence of onetime charge(s) related to items such as inventory or goodwill write-downs. The auditors will often exclude such items when establishing materiality.

- The impact of noncash items on the users of the financial statements. Primary financial statement users may not consider the noncash amounts to be material to their interests as investors or debt holders. This typically occurs because they’re interested in utilizing cash available to pay down outstanding debt.

REVENUE RECOGNITION AND ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Revenue recognition is one likely area of investigation by the auditors, partly because it’s a particular risk for fraud. In many companies, there are incentives, opportunities, and rationalizations connected with revenue that could lead to fraud or serve as fraud indicators, including recognizing sales in the wrong period in an attempt to manage or manipulate sales, the improper use of “bill and hold” (when a company recognizes revenue before delivery takes place) or “ship in place” (this allows a contractor to get paid even though it hasn’t actually shipped the items) sales when not part of contract agreements, and return rights.

The auditors will review and confirm significant sales contracts and terms around the financial year-end or “cutoff.” They will likely obtain detailed sales data for a range of days before and after the cut-off date. If there’s a higher concentration of sales (and higher risk) at year-end, then the testing may be expanded. The auditors will perform revenue recognition control testing over “occurrence assertion” that indicates whether the revenue is properly recognized.

Cash collections will be verified using a sample of revenue items recognized during the year, and the auditors will perform subsequent cash receipt procedures on a sample of receivable balances. To mitigate risks of improper revenue recognition, the auditors will review the revenue and accounts receivable processes and note whether or not the company has appropriate processes and controls in place.

Another area subject to careful review is accounts receivable. The auditors will send accounts receivable confirmations for all company locations and perform alternate procedures when deemed necessary. In conjunction with the audit of revenue, the auditors will review accounts receivable to look for improper revenue recognition. They may also obtain cash proof for material receipts throughout the year since cash proof provides a greater level of detail and makes it easier to spot errors than the standard bank reconciliation.

Fluctuations in sales activity are usually the cause of variations in both revenue and accounts receivable accounts. Acquisitions of other companies can also complicate auditing in this area. Decreased activity due to softening of demand for products caused by lower prices, oversupply, and the timing of billings and cash receipts are explanations for variations. Down payments and cash upon delivery of goods and services may result in decreases in the ratio of receivables to sales. This allows for greater fluctuation from year to year based on the timing of invoices issued and cash collected.

Your company may establish reserves for future sales returns subsequent to when revenue was recognized. The auditors will perform an analysis of return activity as a basis for determining the allowance for returns. The analysis will consider actual returns as a percentage of revenue recognized, and they will apply a rolling average of historical returns (as a percentage of historical revenue) to each month’s revenue included in the historical review.

Any established allowance for doubtful accounts will be evaluated to examine estimated losses resulting from the inability or unwillingness of customers to make required payments. Most companies base such estimates on current accounts receivable aging and historical collections and settlements experience, existing economic conditions, and any specific customer collection issues the company has identified. Companies often identify “tiers” of uncollectible accounts receivable. Changes in reserves as a percentage of gross receivables should be noted and explained.

Suggestions to facilitate an efficient audit:

- Improve internal controls for accounts receivable and the revenue cycle. If the control procedures are sufficient, auditors can rely more on controls and perform fewer substantive procedures. Make sure there are separate functions for recording, authorization, and custody. Proper authorization of transactions can be related to write-offs, credit checks, pricing, and so on. Restrict access to assets, and ensure adequate documents and records are in place, such as sales contracts, prenumbered sales orders, shipping documents, and sales invoices. Perform independent checks on the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger, the general ledger, and the monthly statement to customers. Before the auditors arrive, provide them with the internal control procedures documents related to revenue recognition and accounts receivable. This will help them understand the control procedures related to this area. As a result, they may determine the control risk to be low, thus reducing the extent of substantive procedures.

- Perform overall analytical procedures ahead of time to identify deviations from historical trends and seasonal patterns and to investigate any unusual trends. Since auditors normally use analytical procedures to test revenue, you can, for example, examine the overall balance of accounts receivable, gross profit margin, sales return as a percentage of sales, account write-offs for the current year, receivables turnover, days’ sales in receivables, actual returns as a percentage of revenue, and the amount of past due receivables. Compare the current year’s information to historical data and industry statistics to examine the overall reasonableness from the expectations and prepare explanations where significant deviations exist.

- Prepare explanations and communicate any new or abnormal situations that cause fluctuations from year to year. These may result from business acquisitions, new debts, new leases, and accounting method changes, to name a few. This can facilitate the audit process and ensure that the accounting treatment is evaluated correctly the first time.

- Provide explanations for changes in the allowance for doubtful accounts. The collectability of accounts receivable can be subjective and difficult for the auditors. If there are any changes in products, credit policies, or customer base that might impact estimates, be prepared to provide explanations to the auditors. Also ensure that the allowance and bad debt expense are calculated correctly.

- For your allowance for sales returns, have an established return policy and records to support recorded returns.

- Auditors typically focus on significant sales when they test transactions, so make sure that all sales are recorded properly in the correct period for significant sales contracts. If there’s a higher concentration of sales around the year-end, pay extra attention to whether the sales are recorded in the proper period because the auditors will consider this to be a higher risk area, and they’re likely to extend their testing.

- To promote a smooth audit of the revenue cycle, address any identified issues or errors related to the revenue and accounts receivable cycle as soon as possible before the auditors begin their work. If cash collections don’t occur during a reasonable time period following year-end, you’ll need to provide a reasonable explanation. Prepare reconciliations. For example, clients need to reconcile underlying detailed aging subledgers. To expedite the evaluation process, ensure that any employees who assist the auditors are competent and are available to help during the revenue audit process.

Overall, performing these procedures before the auditors’ arrival can significantly reduce the amount of time the auditors devote to testing this area. Ultimately, this can lead to a reduction of billable hours as well as audit fees.

INVENTORY

Inventory is another area that is a potential risk area for fraud, so auditors examine it closely. There are four aspects of inventory that auditors mainly focus on: recordkeeping, quantities, reserves, and analytics.

Inventory recordkeeping. At year-end, the auditors will obtain inventory details from your largest locations that provide sufficient coverage and select a number of items to test. In addition, work-in-process accounts will be tested by obtaining contracts or subsequent invoices that verify the realizability of the reported amounts.

Inventory records should be consistent with conditions used to determine cost. Where appropriate, the auditor will analyze inventory records based on receipt date, movement, and/or the historical usage of inventory on hand organized by business unit. Once these calculations are prepared, the records are reviewed for each business unit.

Auditor testing is likely to include reconciliations of subledgers to amounts in the general ledger, valuation testing of categories of inventory, and inventory analytic measures (inventory turnover, average inventory, percentage of sales, etc.). To test inventory valuations, the auditors will collect recent invoices issued by vendors and select a sample of items to validate the per-unit prices in the system. In cases where different inventory costing methods are used, the auditor will verify cost calculations from a sample of selected items and trace them to the calculations in supporting documents and records.

Inventory quantities. During the year, you should conduct a number of physical inventory counts at the locations where you maintain inventories. The auditor will review these findings as well as the supporting documents. In addition, auditors will compare a sample from the inventory list to the actual inventory items to verify the existence of the inventory. They’ll also select a sample of inventory items and trace them back to the inventory list to verify its completeness. The goal is for the auditors to conclude that the counts are performed in accordance with company procedures and instructions and that inventory quantities aren’t materially different from the records.

Inventory reserves. When circumstances dictate, inventory gets written down to its estimated realizable value based on assumptions about future demand, technological innovations, market conditions, plans for disposal, the physical condition of products (e.g., unrepairable), and any other significant issues related to possible changes in market value. This procedure leads to establishing inventory reserve accounts, which the auditors will scrutinize. This includes reviewing signed customer contracts, invoices issued after the year-end, or other supporting documentation and asking management about selected open projects.

The auditors will test controls in connection with reserve calculations and will evaluate and review reserves by location. Auditors generally select inventory details from the locations that maintain the largest inventories. Additionally, they will perform substantive procedures on inventory reserves, such as testing the clerical accuracy of general reserve calculations, ensuring that all obsolete inventory items are reserved, and reviewing items for which specific reserves are created.

Inventory analytics. As part of inventory analytics, the auditors set their expectations for inventory based on their understanding of the business, market trends, current financial results, operating characteristics of the company, and experience gained during quarterly reviews. They will compare current expectations and prior-year records to actual inventory variances and investigate all significant changes and absence of expected changes. This gives them expectations regarding whether inventory balances should have increased, decreased, or remain unchanged as a result of changes in sales and cost of sales over the past few years as well as the company’s inventory use policies. The auditors will then look to identify any unusual or unexpected fluctuations. Further, they’ll perform an overall comparative analytical review on inventory balances and reserves to ensure that the relative percentages of inventory balances and balances vs. annual sales are consistent with expectations.

Suggestions to facilitate an efficient audit:

- Discuss the year-end inventory count procedures with the auditors before they arrive. This will help you verify if these procedures are properly designed to address the existence and completeness of your inventory. Document the inventory count procedures and summarize the count and collection results. When the auditors arrive, you can provide a thorough count instruction to help them understand the physical count process.

- Make sure employees who are in charge of inventory have the competence and experience to perform periodic inventory counts. These individuals also should be available to assist auditors during their count to expedite the process and help them quickly identify sample items.

- Cease warehouse operations during inventory audits. If it’s too costly to stop warehouse operations, then shut down sections of the warehouse. Freezing operations can stop production movement and transportation in and out of the warehouse. In addition, any inventories that are received after the start of the physical count should be separated from the counted inventories until auditors are satisfied with the areas.

- Prepare reconciliations to shorten the audit process. Accounting staff should reconcile significant inventory accounts to detailed records and ensure that these items are properly supported before the auditors arrive. A controller or CFO should review all reconciliations to ensure that there are no significant issues. Additionally, accounting staff can prepare a reconciliation of the book value of inventory with the lower of cost or market value in order to verify the accuracy of inventory valuation. These procedures may sound pretty simple, yet auditors often find that the inability to reconcile accounts is one of the biggest and most time-consuming issues.

- Perform a physical inventory count before the auditors do in order to identify any issues that may occur when the auditors observe cycle counts. If it isn’t feasible to perform a physical inventory count for the warehouse, arrange a pre-physical count focusing on items with high value or quick turnover.

- Internal audit staff should perform cycle counts before the external auditors arrive. Make sure the internal auditors have all the supporting documents related to the cycle counts and that all control attributes corresponding to main procedures are outlined in the cycle-count instructions.

- Maintain documentation of reserve calculations to help ensure reserves are determined in accordance with accounting standards. This also helps establish that reserves are consistent with the company’s policies and with the prior year’s records. Documentation should exist to support why specific reserves were created and confirm that the inventory list doesn’t include any similar items that weren’t reserved.

- Perform overall analytical review procedures ahead of time to identify deviations from historical trends and seasonal patterns. Investigate any unusual trends or circumstances, particularly fluctuations greater than certain thresholds from prior years (inventory turnover, average inventory, days in inventory, percentage of sales, etc.). Compare actual inventory variances with expectations, and investigate significant changes (e.g., if sales decrease, clients should expect inventory to increase proportionately) before the auditors arrive. Auditors normally perform these procedures. Performing these procedures in advance yourself may mean the auditors can spend fewer hours on them. Be prepared to provide any explanations regarding abnormal situations.

- Prepare explanations in advance for inventory with slow turnover, such as why there’s continued demand for these materials or products. Be prepared to provide forecasts that support the prediction of future sales of products at a price that would cover the cost of these slow-moving material items. Organize and clean up inventory to avoid unnecessary questions. Auditors may question if inventory is slow-moving or obsolete based on visible clues—for example, if they notice old inventory tags, dust, or rust.

- Organize facilities to ease observation of inventory so that auditors are confident with the accuracy of the count. If inventories are held by third parties, such as in a public warehouse, managers who are in charge of the inventories should encourage the third party to conduct a physical inventory count on the same date as the main warehouse inventory count. Auditors may consult with the third party to confirm the existence of the inventory held by the public warehouse.

- Leave a clear trail of evidence for auditors to follow your work. For example, if the controller checks the work of an assistant, there should be a trail of references that auditors can verify. Further, checklists should be prepared for any closing or multiple-step activities. This will allow auditors to clearly see where information comes from and not have to spend time searching for source documents.

PREPARE IN ADVANCE

Audits can be a long, painful, and expensive process. Even though companies aren’t able to change certain aspects of the audit—such as accounting regulations, audit requirements, or increases in audit fees—one area that companies can help influence more directly is the amount of time auditors need to complete the audit. If you take the time to become knowledgeable about how the auditors are likely to structure the review, it can lead to cost savings and benefits for your company. Detailed preparation and good communications with auditors can lead to a less stressful experience and less expensive audit.

Audits should be viewed as an investment in the future of your company. It’s an opportunity to obtain a valuable third-party perspective on your financial systems, discuss difficult areas you have encountered or concerns you may have about your company’s operations and activities, and get answers to questions you may have about your job or business. If you’re well prepared for the audit, you may be able to reduce the time and expense involved.

December 2019