Accounting professionals are often asked to join charity boards and, by extension, audit committees because of their financial expertise and experience. Although most are likely to have significant accounting experience, it’s less likely that the experience is in the not-for-profit (NFP) world. Because the NFP world has some significant differences in the audit process, prospective and current NFP board and audit committee members share a common interest in understanding that process.

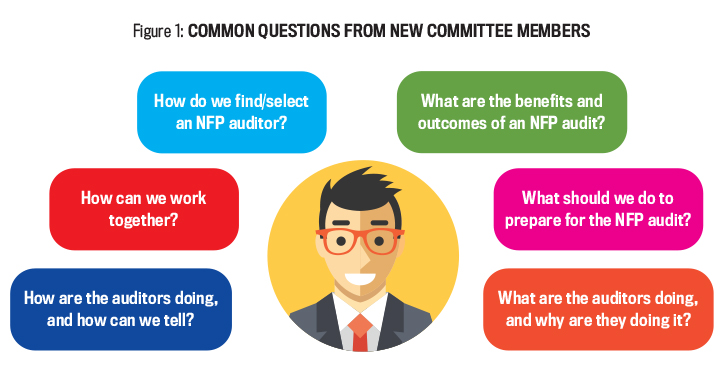

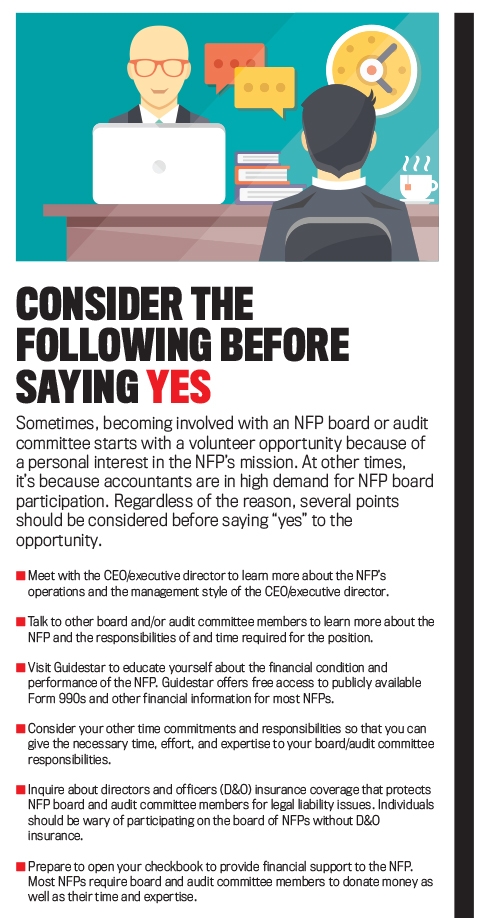

Management accountants should have a guide that’s useful both when joining an NFP board and when asked to explain the NFP audit process to new board and audit committee members. To that end, we address common questions (see Figure 1) for new NFP audit committee members and issues to consider before joining (see “Consider the Following Before Saying Yes”).

AUDITS FOR NFPS IN A NUTSHELL

The first step in fulfilling an audit committee role is to understand why the NFP is seeking audit services and what an NFP audit entails. NFP audits occur because important stakeholder groups require assurance of accountability for funds provided. Most commonly, private foundations and other major donors require NFP audits as a condition of their funding or ongoing support. Similarly, NFPs that receive federal grants above a certain threshold (currently $750,000) are required to have a specific audit (called Uniform Guidance) to ensure the grantee NFP is in compliance with federal laws and is using grant funds appropriately. In some cases, boards engage auditors simply to help fulfill their stewardship obligation to donors.

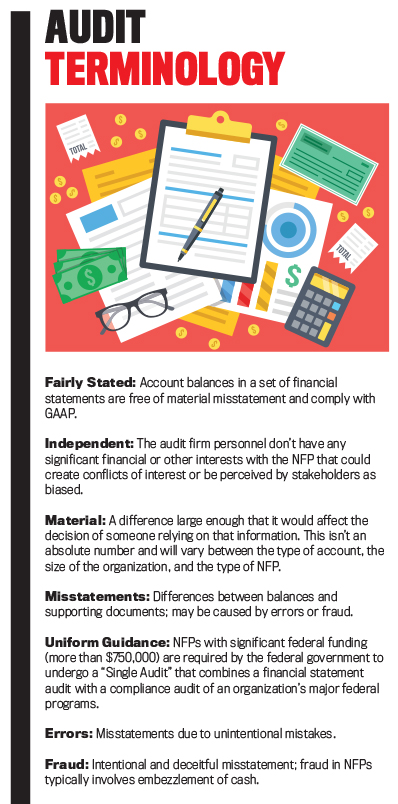

A financial statement audit involves an examination of the NFP’s financial reporting by an independent auditing firm. The auditors apply Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS), just as they would with other financial statement audits. Auditors of NFPs that receive federal grants must also follow the additional auditing rules specific to governmental accounting, termed Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS) or the Yellow Book. Finally, the NFP’s financial statements (and schedule of federal grants, when applicable) are compiled, and an audit opinion is issued.

Examining financial reporting includes seeking to understand the NFP’s system of internal controls and testing those internal controls for deficiencies (e.g., where they’re missing, not working, or not working as intended). Just as they do with for-profit organizations, internal controls provide the checks and balances within an NFP to safeguard assets and ensure reliable financial reporting. But NFPs often face unique challenges in establishing the most important of the internal controls: segregation of duties.

NFP audit committees must often balance competing goals—being accountable to donors for how funds are used in meeting their mission while still investing in sufficient administrative resources. As a result, NFPs often have limited financial staffing, which can lead to the same person being responsible for more than one aspect of asset management (custody/authorization, recording, and reconciling the records). Audit committees should be aware of this risk and design compensating controls or request the auditor’s help in designing such a system.

Examining financial reporting also includes comparing account balances with supporting documentation (i.e., substantive tests), focusing on high-risk account balances. Common high-risk accounts for NFPs include donations revenue, deferred revenue, investments, and cash. In addition, auditors are likely to focus on the critical functional expenses classifications (i.e., program, administrative, and fundraising) by which donors evaluate the NFP’s efficiency and effectiveness.

The main goal of these tests is to ensure that the balances rolled into a set of financial statements aren’t materially misstated and that they comply with standardized accounting rules. These rules are created and updated regularly by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and collectively are termed Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). (See “Audit Terminology” on p. 50 for a list of common audit terms.)

Audit committees interact with the auditors at three milestone points: during the auditor selection/continuation process, when the engagement letter is issued and the pre-audit conference is held, and at the end of the audit.

THE SEARCH BEGINS

NFPs often engage audit firms for many years to take advantage of auditor competencies and efficiencies created through experience. But NFPs sometimes will require auditor changes to prevent complacency in the audit process. As one audit committee member told us, her NFP decided to change auditors because they “thought it would be helpful to have different eyes on the project.”

The search for a new auditor begins by issuing a request for proposal (RFP). The RFP invites several audit firms to bid for the audit. Similar to an employment advertisement, the RFP should describe the required and preferred qualifications for the audit firm. For example, if the NFP receives significant federal grants, then the auditor must be specifically qualified. The RFP also details the NFP’s operational and financial characteristics as well as provides audit time frames and deadlines. Good RFP process practices include:

- Timeline for Auditor Search. A timetable should be created to establish time frames with reasonable deadlines to perform and complete the auditor search.

- Specialization. RFPs should only be sent to audit firms with NFP expertise. Additionally, NFPs requiring specialized knowledge (education, health-care, Uniform Guidance auditing) should narrow their search to audit firms with specialization in these areas.

- Signals of Auditor Quality. This can be very difficult to ascertain through the proposal process, as many proposals are similar. But some signals that are available include the presence of a peer review report (i.e., a report where the auditor itself is reviewed) and the names and experience levels of actual audit personnel to be assigned to the engagement.

- Good Communicators. Most auditors are very good at communicating audit results and findings. But some are especially good at understanding their audit committee (and board of directors) audience and articulating how financial and internal control issues impact their NFP client. Look for auditors who spend the necessary time to consider their audience and explain things in an understandable way.

- Price Matters to a Point. All proposals will include a proposed audit fee. Most NFP audit engagements are “fixed fee” rather than “billed hourly.” This means that the stated fee is the maximum amount the NFP will pay for the audit, barring any unforeseen situations. But the saying “you get what you pay for” applies to audits as much as anything else. Beyond the audit fee amount, NFPs should consider qualitative factors such as auditor quality, specialization, client service, and expertise/experience in their selection process.

- Cybersecurity. NFPs of all sizes are increasingly exposed to cybersecurity threats. Many collect personal information from donors and other stakeholders, such as credit card information, addresses, Social Security numbers, and even medical records. NFPs also hold sensitive information about their employees. But NFPs often have relatively unsophisticated information systems (many smaller NFPs only use Quickbooks and Excel) and lack expertise in information technology. NFPs should consider hiring audit firms that are able to help them understand their cybersecurity needs.

The RFP process concludes by narrowing down the audit firm bids to the top choices (two or three maximum), hosting in-person interviews with the finalists, and selecting the winning firm. Most of the time, the best final overall choice will be obvious. Asked for practical advice on final auditor selection, an experienced audit committee member replied, “At the end of the day, who do you have the most connection with, and who’s going to be the most responsive to you?”

RULES OF ENGAGEMENT

Once an NFP has completed the RFP process and selected an auditor, the next step is for both parties to establish and document their objectives and responsibilities for the audit. This is essential, and auditing standards require these to be formalized with a written engagement letter. The engagement letter usually includes the following sections:

Engagement Terms. Summarizes the audit objectives, the auditing standards (e.g., GAAS) the auditors will follow, and the accounting framework (e.g., U.S. GAAP) applicable to the NFP financial statements.

Responsibilities and Limitations. Outlines the auditors’ and NFP’s responsibilities as well as the inherent limitations of the audit. This section aims to minimize or eliminate any misunderstandings that may arise.

Documentation. A general overview of the documents reviewed and produced by the audit. Ideally, an NFP should provide complete access to all financial documentation, records, and files, as well as minutes from the board of directors, procedural manuals, contracts, grant and third-party agreements, and other appropriate items as needed. Auditors often include a “prepared by client” (PBC) list that details the documents needed. Finally, the section defines the ownership and retention requirements for audit documents.

Timing and Fees. Provides a timeline for audit completion and establishes the cost of the audit. Audits with a tight deadline or during accounting “busy season” often cost more, while audits performed off-season may be provided at a discount. Issuances of new accounting rules could also affect the audit timeline and cost.

During this pre-audit phase, the auditors and audit committee often meet to discuss the audit work plan and outline the overall audit strategy. The work plan identifies the financial reporting processes and account balances of greatest concern to the auditor. For example, a university with a large endowment and many types of investments will have a different set of concerns relative to a local animal rescue that relies on annual donations and has only basic banking accounts, and an NFP that receives federal funding will have different risks than an NFP that receives no federal funding. Every audit will have its own specific risks and concerns.

The auditors will also discuss any new auditing and accounting rules relevant for the current year’s audit. For example, the FASB recently issued a new accounting rule (Accounting Standards Update 2016-14) that amends how NFPs report information in their financial statements. In conversations with the audit committee, the auditors will describe how this new rule impacts and changes the current year’s audit and financial statements and will seek to ensure that the NFP understands the required changes going forward.

The NFP audit committee’s role is to provide input to the auditors on the perceived risks, internal control issues, and any other areas of special concern. Auditors will consider this input and often incorporate it into their audit work plan.

FINAL AUDIT WRAP-UP

In the final phase, the audit committee members attend the auditor’s presentation of financial statements and the audit report. In almost all cases, the auditors will present their findings to the audit committee at the end of the engagement. Typically, the auditors are represented by the audit partner and manager/supervisor. The audit partner is responsible for the overall audit engagement, while the audit manager/supervisor manages the frontline audit process.

The auditors will often start their presentation by saying that the audit opinion is unmodified (clean). Almost all audit opinions are clean, so this is good news, but it’s also very much expected news. The auditors will then discuss the basic financial statements and the related notes to the financial statements. Their focus will be on significant trends, such as “donations increased by 4%, program expenses decreased by 2%, operating cash flows improved by $30,000, etc.” They also will discuss important required disclosures.

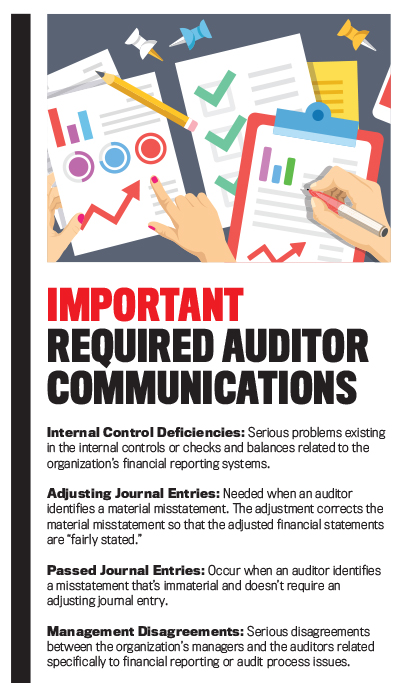

Auditors are required to tell the audit committee certain things (see “Important Required Auditor Communications”). These are outlined in the audit committee letter or, to use auditor terminology, the “SAS 114 letter.”

Auditors may also present additional information about the organization’s financial statements. For example, auditors often write management letters that identify minor internal control deficiencies (beyond report requirements) and other suggestions for improving the organization’s financial reporting systems. This is also the time for the audit committee to ask the auditor questions about the audit and about the NFP’s financial standing (see “Topics to Cover with the Auditor”). A member of an NFP urged, “Pick the brains of the auditors or audit partner—this is the big benefit of an audit.”

DELIVERY OF THE REPORT AND STATEMENTS

A few weeks after the final audit committee presentation by the auditors, the audit report and the audited financial statements are issued. The audit report is addressed to the NFP’s board of directors and is dated as of the last day the auditor performed substantial audit procedures on the engagement. This date is important because it determines the period of auditor responsibility subsequent to year-end. Most important, the report provides the unmodified opinion. The audited financial statements are provided in the pages following the audit report.

The process of selecting an NFP auditor and the NFP audit itself doesn’t need to be overwhelming. Management accountants’ core competencies in decision making, planning, and reporting bring needed expertise to NFP audit committees. We’ve highlighted significant aspects of the NFP audit process, including the auditor selection process, communication between the NFP and auditors, and an overview of audit benefits and outcomes. By demystifying the NFP audit process, we hope we’ve encouraged management accountants to donate their time and expertise to worthy NFP organizations as audit committee members.

TOPICS TO COVER WITH THE AUDITOR

Audit committee members may find that it’s difficult to ask the auditor good questions. The following provides a list of things to think about when generating questions for the auditor:

Keeping Up with the Neighbors?

Auditors, especially those that specialize in NFPs, perform audits on a wide breadth of organizations. They’re in a great position to provide comparative feedback about performance and processes. Because of their experiences auditing other companies, they can advise audit committees on the kinds of practices and processes that are typical among similar organizations—as well as ones that might be unusual for an organization in the same industry or of similar size, structure, etc.

What’s New?

The constant barrage of new accounting standards, regulations, best practices, or other issues impacts every organization’s future. Auditors know these issues will impact the organization’s financial situation and provide advice on how to implement these changes.

Taxes? I Thought We Were Tax-Exempt.

Many not-for-profit organizations are required to file Form 990 with the IRS annually and make the form publicly available for donors and other interested parties. Form 990 is an informational filing that discloses financial data and information on governance and managerial practices. Surprising to some, it also reports compensation amounts for managers and higher-paid (greater than $100,000) employees. The audit committee should ask the auditor about any Form 990 disclosure issues and should review the form prior to its filing.

Did Everything Get Fixed?Deficiencies and other findings from prior years’ audits should be corrected in a timely manner by the organization.

For Additional Information

The National Council of Nonprofits has created a Nonprofit Audit Guide to assist boards and audit committees. The guide can be found at www.councilofnonprofits.org.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) provides access to governmental auditing standards (GAGAS) along with other resources on its website www.gao.gov/yellowbook/overview.

The U.S. Government also provides a website and mobile app about federal grants and Uniform Guidance. More information is available at www.grants.gov/web/grants/home.html.

The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) creates best practices and frameworks for internal controls and fraud deterrence. COSO resources are available at www.coso.org.

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issues financial reporting standards applicable to NFPs. The FASB’s website is www.fasb.org.

The Not-For-Profit Advisory Committee (NAC) acts as a liaison group between the FASB and the NFP community. More information about NAC is available at www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Page/SectionPage&cid=1176156543050.

The Internal Revenue Service provides NFP-specific information about tax-exempt status, annual reporting, and filing requirements at www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits.

Guidestar offers free access to Form 990 tax returns and other information on more than 1.8 million IRS-recognized tax-exempt organizations at www.guidestar.org/Home.aspx.

June 2018