This article is based on a study funded by the IMA® Research Foundation

Yet while fraud in nonprofits has received increased attention during the past 10 years, the organizations remain an understudied population in the context of internal controls and fraud. More specifically, a majority of research dealing with fraud in nonprofits has focused on the victim organizations. While such research is valuable, the question of whether the organizations that experienced fraud are different in some significant way from those that, thus far, have escaped it is still unanswered. This isn’t a trivial question. Nonprofit organizations commonly view fraud as a matter of misfortune. The conventional wisdom of fraud prevention and auditing strongly disputes this view, but empirical evidence is needed to convince some organizations otherwise.

The aim of our research is to better understand the nature of internal controls in nonprofits and how those controls affect the incidence of fraud. The research can provide benefits to nonprofits either by identifying best practices in nonprofit internal controls and promoting their use or by identifying existing weaknesses in nonprofit internal controls.

The aim of our research is to better understand the nature of internal controls in nonprofits and how those controls affect the incidence of fraud. The research can provide benefits to nonprofits either by identifying best practices in nonprofit internal controls and promoting their use or by identifying existing weaknesses in nonprofit internal controls.

FRAUD IN NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONS

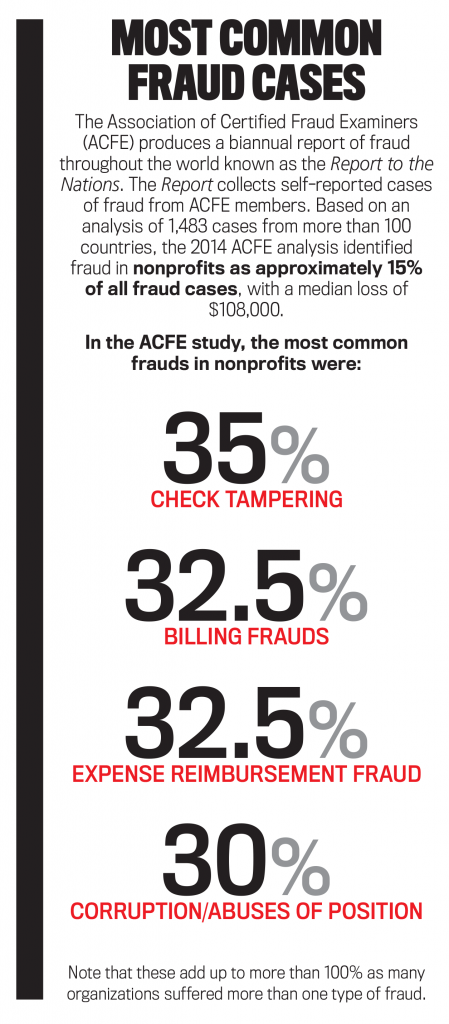

Numerous studies over the last decade point to increases in both the frequency and severity of fraud in organizations of all sizes and across industries. The economic impact of these losses has been significant. In its 2014 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) estimated that organizations lose up to 5% of their annual revenue to fraud, with the median loss to nonprofits estimated at $108,000. As high as these numbers appear, they may still be misleading in understanding the damage that nonprofits suffer when they are victims of fraud. First, smaller organizations, such as most nonprofits, suffer disproportionately larger damages from their frauds even though the amounts are small when compared to the median. Second, the damage from fraud not only encompasses monetary losses but also damages employee morale, organizational reputation, and business relationships. This loss of reputation can be particularly devastating in the case of nonprofits that depend on their reputation and the goodwill of donors to raise revenue.THE CULTURE OF NONPROFITS AND THE RISK OF FRAUD

In addition to the increased damage that fraud causes, nonprofits also face potentially greater risks of becoming victims. A wide range of studies have found that nonprofits may be at higher risk for the occurrence of fraud than for-profit organizations because of the nature of their mission and their management structure. For example:- Governing boards are often composed of volunteers who lack expertise in financial management.

- Directors of nonprofits frequently lack the skills for effective financial management.

- Daily financial management is frequently under the control of a single individual who isn’t otherwise subject to the financial controls and oversight normally found in profit-making entities.

- The organizational culture of nonprofits leads them to believe that their charitable purpose is sufficient to protect them against fraud.

- Revenue streams are difficult to control or verify.

OUR STUDY

Given the risk nonprofits face and potential gains from better internal controls, a key set of questions to consider is: Do nonprofits that experience fraud have internal controls that are different from those that don’t experience fraud? Do they make appropriate improvements to their internal controls once the fraud has been uncovered? In our study, we gathered data through an email survey sent to 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations provided by GuideStar, a major information service that specializes in reporting on U.S. nonprofits. The sample was based on operating budget and included all the nonprofits in GuideStar’s database with an email address and a budget greater than $500,000. Thus we sent the survey to approximately 20,000 nonprofits. The survey yielded 1,396 usable responses, with 269 (19%) of the respondents reporting some type of fraud during the last five years and 1,127 (81%) reporting no instances of fraud. The survey instrument was a modified version of one that was previously used for private industry, cooperatives, and community health centers. Respondents who experienced fraud reported on:- Methods of fraud,

- Methods of detection,

- Existence and frequency of internal control practices (before and after the fraud),

- Total dollar losses,

- Amount spent to improve internal controls, and

- Perceived vulnerability to fraud (at the time of the survey).

How Much Did the Fraud Cost?

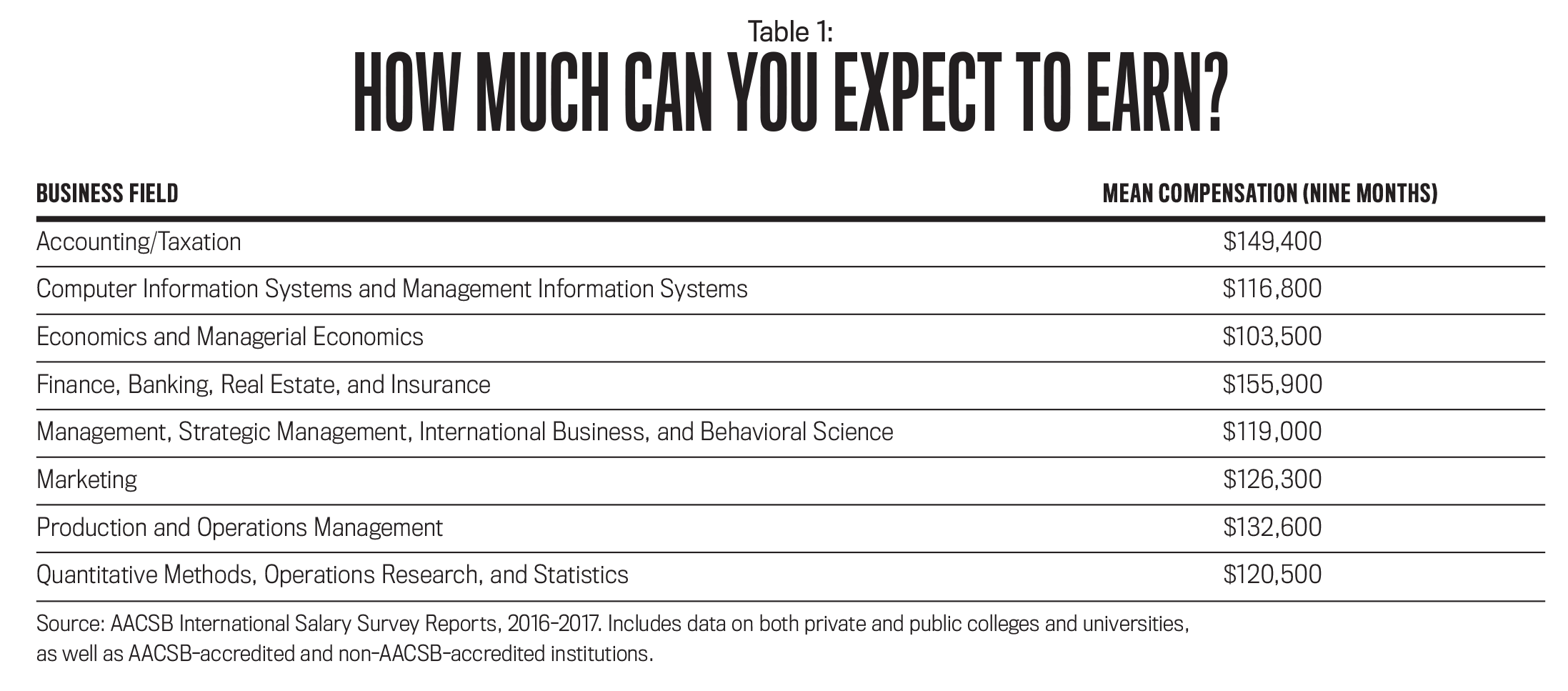

The average dollar losses by method of fraud are summarized in Table 1. Note that the number of instances exceeds the number of respondents because many organizations experienced more than one type and one instance of fraud. As Table 1 shows, the most frequent fraud incident is the theft of cash, which has an average estimated loss of $16,174. The second most frequent form of fraud is check fraud (including forgery), with an average loss of $9,888 per incident. Conflict of interest occurs relatively infrequently yet has the largest reported average loss of $53,989.

Were There Any Changes After the Fraud?

For organizations that reported fraud, a number of practices showed a statistically significant difference in frequency at the time of the fraud and currently. Practices done more frequently after fraud occurred than before are:- Check of employee references/job history

- Board review of individual expenses

- Board training in financial management

- Job rotation

- Vacation policies enforced

- Bonding of employees

- Review levels of bonding

- Physical security reviews

- Issuing of receipts for fines/fees

- Review of specifications for insurance quotes

- Presigning of checks

- Spending more than budget

Have Internal Controls Changed Enough?

A second question concerning nonprofits that experienced fraud is whether they have strengthened their internal controls enough. Unfortunately, we can’t discuss the best method—performing assessments of internal controls in individual organizations—because of resource constraints and the anonymity of the organizations that responded. So we examined two proxy measures: How closely do the improved controls resemble those in nonprofits that didn’t experience fraud, and have both categories of nonprofits made similar investments in internal control?Comparing Nonprofit Internal Controls

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing the frequency of the financial practices in organizations with fraud vs. the organizations without fraud shows that there are two control practices that are still performed less frequently in organizations that have experienced fraud than in those without fraud. They are review of expenses by the board of directors and enforcement of vacation policies. And organizations that have experienced fraud perform two other controls more frequently than those that haven’t. They are requiring multiple signatures on checks and job rotation. The survey instrument doesn’t examine causality between the presence or absence of specific internal controls and fraud, but there’s a strong logical connection between the two based on the literature of auditing and fraud prevention. First, the risk of occurrence for all the frauds that the survey examined can be mitigated by the internal control practices for which we collected information, whether singly or in combination. Second, all the practices were performed more frequently after the fraud occurred than before. Third, as we just mentioned, in only two instances were the practices performed less frequently than in organizations that didn’t experience fraud, while two others were performed more frequently. Though individual nonprofits may still be at risk for fraud, overall they have adopted practices that deter fraud, and to a degree that makes them closely resemble nonprofits that escaped fraud.Investment in Internal Control

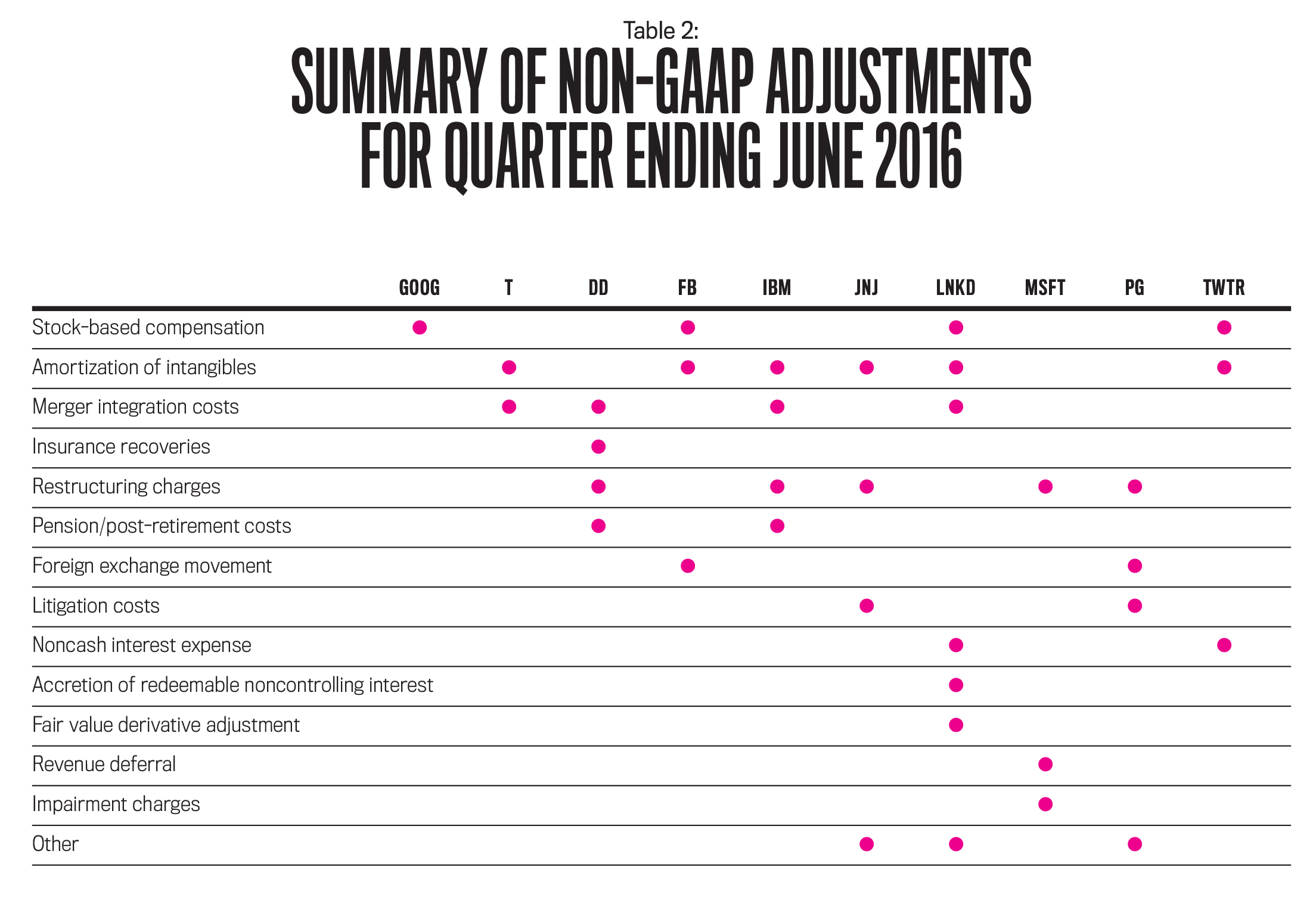

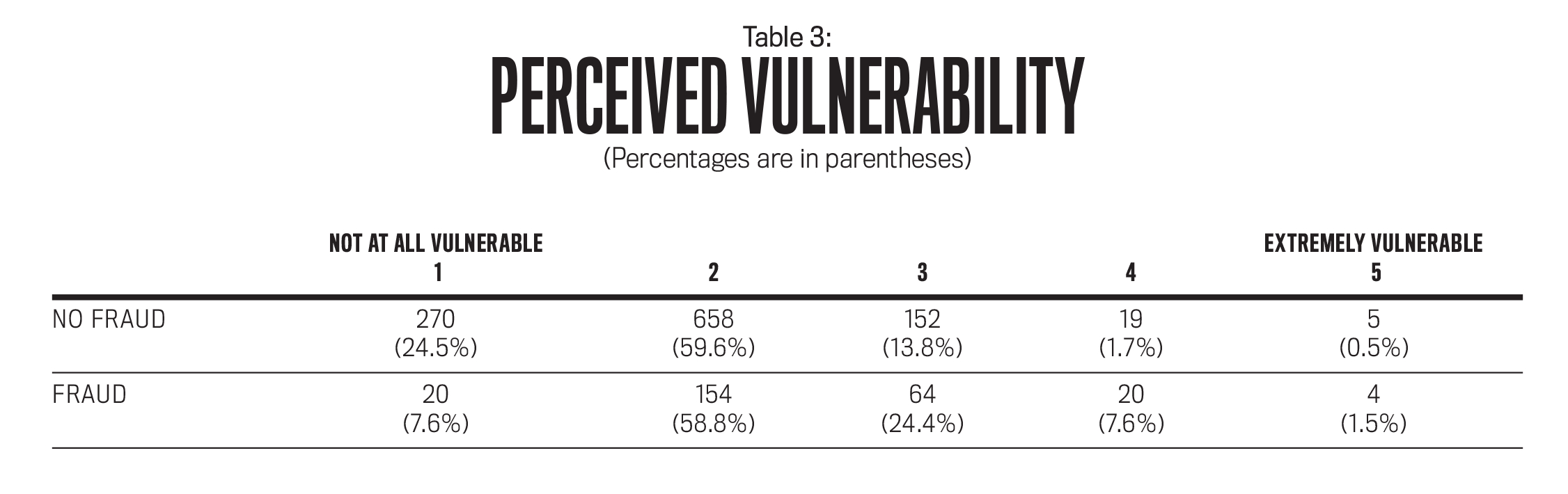

Monitoring and assessing risk is an integral part of internal control. An organization’s environment and objectives constantly change, so its internal controls must be adapted to these changes. In 2013, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) released its updated Internal Control—Integrated Framework that companies could use for guidance in this area. (The original was released in 1992.) One measure of this is investment in internal control. We asked organizations that didn’t experience fraud and those that did to provide their costs for improving internal control, both current and projected. The results are presented in Table 2. Based on their investments, organizations with fraud have spent about as much on steps already taken to improve internal controls as organizations without fraud. Further, those that have had fraud plan, on average, to spend more on improving internal controls than those without fraud. The cause of higher future investment is unclear, although perceived risk may play a part, as Table 3 indicates.

Based on their investments, organizations with fraud have spent about as much on steps already taken to improve internal controls as organizations without fraud. Further, those that have had fraud plan, on average, to spend more on improving internal controls than those without fraud. The cause of higher future investment is unclear, although perceived risk may play a part, as Table 3 indicates.

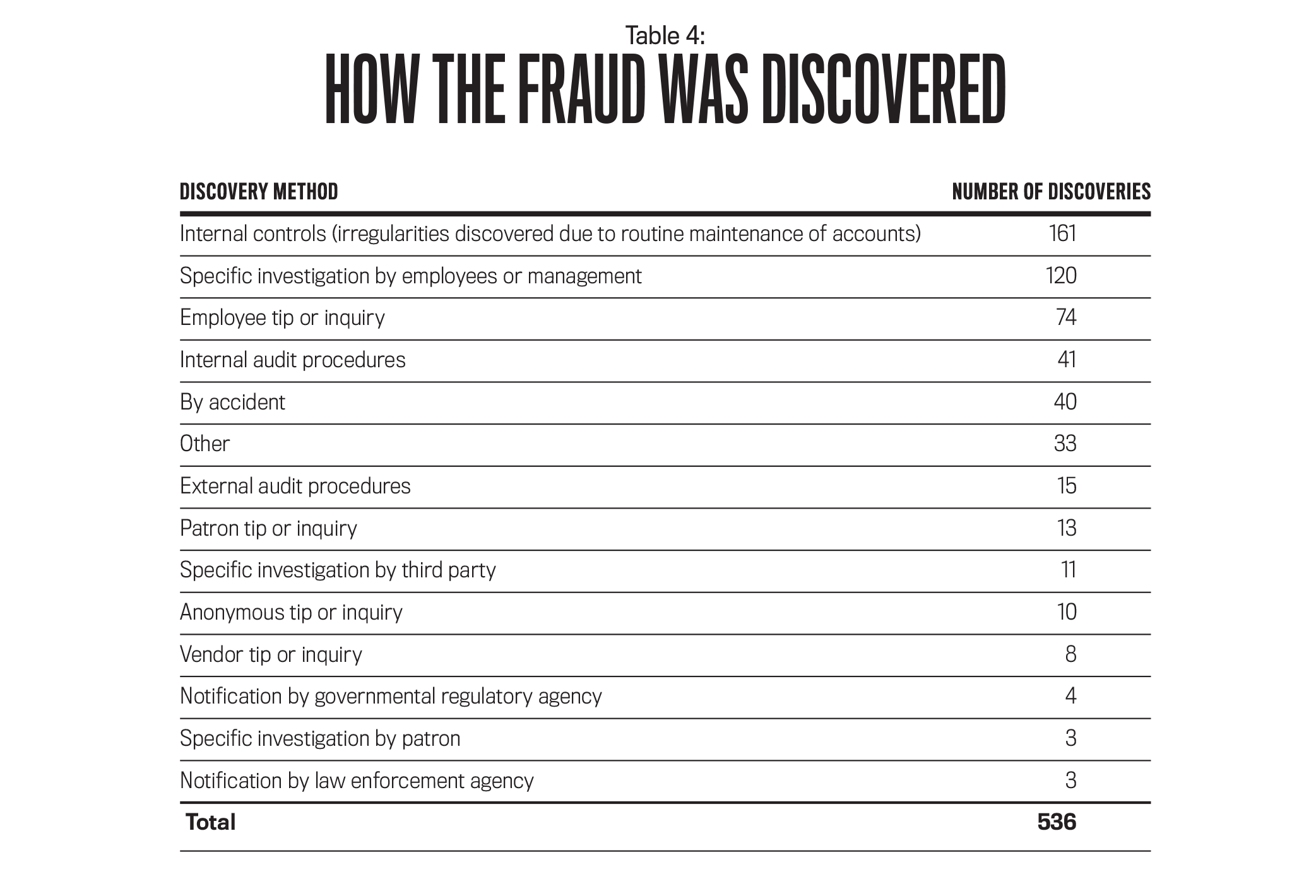

Not surprisingly, a higher percentage of organizations that haven’t experienced fraud don’t feel as vulnerable as those that have had fraud. Similarly, organizations that have experienced fraud feel more vulnerable (3, 4, or 5) to fraud than those that haven’t. It’s also interesting to note how the fraud was discovered. Table 4 reinforces the need for internal controls as almost one-third of the frauds were uncovered because of internal controls.

Not surprisingly, a higher percentage of organizations that haven’t experienced fraud don’t feel as vulnerable as those that have had fraud. Similarly, organizations that have experienced fraud feel more vulnerable (3, 4, or 5) to fraud than those that haven’t. It’s also interesting to note how the fraud was discovered. Table 4 reinforces the need for internal controls as almost one-third of the frauds were uncovered because of internal controls.

TAKE THE RIGHT STEPS

Organizations frequently resist efforts to improve their internal controls and to implement antifraud programs. They argue that fraud and abuse occur as the result of determined criminals. In other words, the organization had the misfortune to employ someone determined to commit fraud. The feeling may be particularly pervasive in nonprofits, which feel that their charitable mission provides unique protections. But as our study indicates, this doesn’t seem to be the case. There are significant differences between those organizations that experienced fraud and those that didn’t. In particular, nonprofits that experienced fraud significantly improved their internal controls after the fraud by increasing the frequency of beneficial financial practices. After the improvements, these nonprofits more closely resembled those organizations that didn’t experience fraud. Fraud is costly, both financially and nonfinancially. Good internal controls can reduce the occurrence of fraud and, if fraud occurs, can help discover the incident.A FAMOUS CASE

One of the most famous cases of nonprofit fraud in recent history involved William Aramony, CEO of the United Way for 22 years until his retirement in 1992 and subsequent indictment and conviction for fraud in 1995. Together with CFO Thomas J. Merlo and Partnership Umbrella President Stephen J. Paulachak, Aramony was indicted on 53 counts of fraud and was accused of embezzling more than $1.2 million from United Way. The frauds ranged from altered expense reports to hide lavish trips to siphoning funds through a spin-off organization, United Way Partnership Umbrella. It appears that Aramony was able to succeed in his relatively straightforward fraud from a combination of coopting his CFO and general inattention to his spending. All of Aramony’s expenses were required to be approved by members of the board of directors, but this appears to have occurred rarely, if ever. Members of the board also appear to have disregarded warning signs of irregularities when they received them. The then-chairman of the board for the United Way received an anonymous letter in 1990 warning that United Way was being looted from the inside. According to his testimony, he “asked around” to see if anyone had “heard anything.” Hearing nothing, he dropped the matter. The story ultimately became public, not through internal controls but through reporting by The Washington Post and Regardie’s (a Washington business magazine). The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and the U.S. Postal Service opened investigations, and Aramony was subsequently convicted of fraud and sentenced to seven years in prison. The takeaway from this is that many frauds, even in major organizations, aren’t very sophisticated. Catching Aramony’s conduct wouldn’t have required a deep knowledge of accounting, merely the will to look closely at how large sums of money were being spent and whether they seemed reasonable. In Aramony’s case, if United Way had even rudimentary internal controls, or if the board of directors had performed its oversight duties, the fraud might never have taken place, or at least might have been caught early.FURTHER READING

Steve Albrecht, Chad O. Albrecht, Conan C. Albrecht, and Mark F. Zimbelman, Fraud Examination and Prevention, 5th ed., Cengage Learning, Boston, Mass., 2014. Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, 2014, www.acfe.com/rttn/docs/2014-report-to-nations.pdf. Thomas Buckhoff and Abbie Gail Parham, “Fraud in the NON profit sector? You bet.” Strategic Finance, June 2009, pp. 53-56. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), Internal Control--Integrated Framework, 2013, www.coso.org. Donna Dietz and Herbert Snyder, “Internal Control Differences between Community Health Centers that Did or Did Not Experience Fraud,” Research in Healthcare Financial Management, January 2007, pp. 91-102. Ernst & Young (EY), Growing Beyond: a place for integrity, 12th Global Fraud Survey, 2014, www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Global-Fraud-Survey-a-place-for-integrity-12th-Global-Fraud-Survey/$FILE/EY-12th-GLOBAL-FRAUD-SURVEY.pdf. Janet Greenlee, Mary Fischer, Teresa Gordon, and Elizabeth Keating, “An Investigation of Fraud in Nonprofit Organizations: Occurrences and Deterrents,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, December 2007, pp. 313-325. Kristy Holfreter, “Determinants of Fraud Losses in Nonprofit Organizations,” Nonprofit Management & Leadership, Autumn (Fall) 2008, pp. 45-63. Independent Sector, The Sector’s Economic Impact, www.independentsector.org/about/the-charitable-sector. KPMG, Integrity Survey 2013, https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2013/08/Integrity-Survey-2013-O-201307.pdf . Tyge-F. Kummer, Kishore Singh, and Peter Best, “The Effect of Fraud on Risk Management in Not-for-profit Organizations,” Corporate Ownership & Control, Vol. 12, Issue 1, 2014, pp. 641-655. John E. McEldowney, Thomas L. Barton, and David Ray, “Look out for Cletus Williams,” The CPA Journal, December 1993, pp. 44-47. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Global Economic Crime Survey 2016, www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/advisory/consulting/forensics/economic-crime-survey.html. Joyce Rothschild and Carol Milofsky, “The Centrality of Values, Passions, and Ethics in the Nonprofit Sector,” Nonprofit Management & Leadership, Winter 2006, pp. 137-143. Herbert Snyder, “The Sophomore Slump: Improving Internal Controls in Small Businesses Once They Succeed,” Fraud Magazine, November/December 2004, pp. 45-47, 61. Herbert Snyder and James Clifton, “Stealing from the Collection Plate: Fraud in Churches and Religious Groups,” Fraud Magazine, November/December 2005, pp. 20-23, 46. Herbert Snyder and Donna Dietz, “Fraud in Community Health Centers,” Journal of Forensic Accounting, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 133-145. Herbert Snyder and Julia Hersberger, “Public Libraries and Embezzlement: An Examination of Internal Control and Financial Misconduct,” The Library Quarterly, January 1997, pp. 1-23. Richard A. Turpen and Frank M. Messina, “Fraud Prevention and the Management Accountant,” Management Accounting, February 1997, pp. 34-37. Urban Institute, The Nonprofit Sector in Brief 2014, www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/413277-The-Nonprofit-Sector-in-Brief--.PDF. Joseph Wells, Principles of Fraud Examination, 4th ed., John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, N.J., 2014. Save Save Save Save Save Save Save Save Save Save Save

March 2017