Despite significant strides, there’s still a long way to go. Large protests in 2014 and 2015 against government corruption throughout Brazil added visibility and a sense of urgency to the country’s antibribery efforts, while a recent corruption case involving Brazil’s own national oil company, Petrobas, underscores that work remains in implementing and, more importantly, enforcing antibribery laws.

Given the critical role played by Brazil in the global economy, the current and potential success of these efforts can impact other countries and businesses around the world. Brazil actively trades with more than 100 countries and had an estimated $189.7 billion in exports and $143.9 billion in imports in 2016. Much of that involves trade to and from China and the United States.

The expansion of the country’s foreign trade means the issue of foreign bribery is becoming increasingly relevant for Brazilian companies, while the pervasiveness of bribery and corruption means non-Brazilian companies must consider the added risks of doing business within the country. The anticorruption efforts also are important for Brazilian regulators and policy makers in their attempts to maintain the attractiveness of Brazil as a favorite trading partner and location for foreign direct investment (FDI). In addition, the process and methods used in Brazil can help shed light on some of the obstacles and problems facing other countries and governments in their attempt to align antibribery regulations with international standards. In this era of global business, companies must have a deeper awareness of these matters in order to make better-informed investing and risk management decisions in any country.

BRAZIL IN THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

With the ninth-largest economy in the world, Brazil is an attractive destination for inbound foreign direct investment—especially considering the size of its consumer market, its growing middle class, and the fact that it hosted the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics—two notable events that required huge investments.

Moreover, according to data published by the Brazilian Geography and Statistics Institute, Brazil presents a prime opportunity for investors because of the market potential of its current population of approximately 205 million—almost half of which is younger than 20 years of age. Additionally, Brazil has a stable economy with controlled inflation and modern telecommunications and bank infrastructures.

According to the World Economic Indicators from the World Bank, Brazil received more than $50 billion in net inflows from foreign direct investments in 2008, which made it the 13th largest recipient of FDI in the world and one of the largest recipients of FDI in Latin America. In 2015 alone, foreign direct investment in Brazil reached $75.1 billion, an increase of 48% in FDI since 2008.

The total foreign direct investment in Brazil was $531.4 billion at the end of 2014. And with $111.7 billion of the total foreign direct investment in Brazil, the U.S. was considered to be the biggest foreign investor in the country, followed by the Netherlands with $71.4 billion and Spain with $59.5 billion.

FIGHTING CORRUPTION IN BRAZIL

According to the most recent Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) from Transparency International, Brazil ranked 79th among 176 countries in 2016 with a CPI of 4.0. (The CPI ranges between 0 and 10; the lower the CPI, the greater the corruption degree in the country.) Table 1 shows Brazil’s CPI by year along with its respective ranking among the countries in the index.

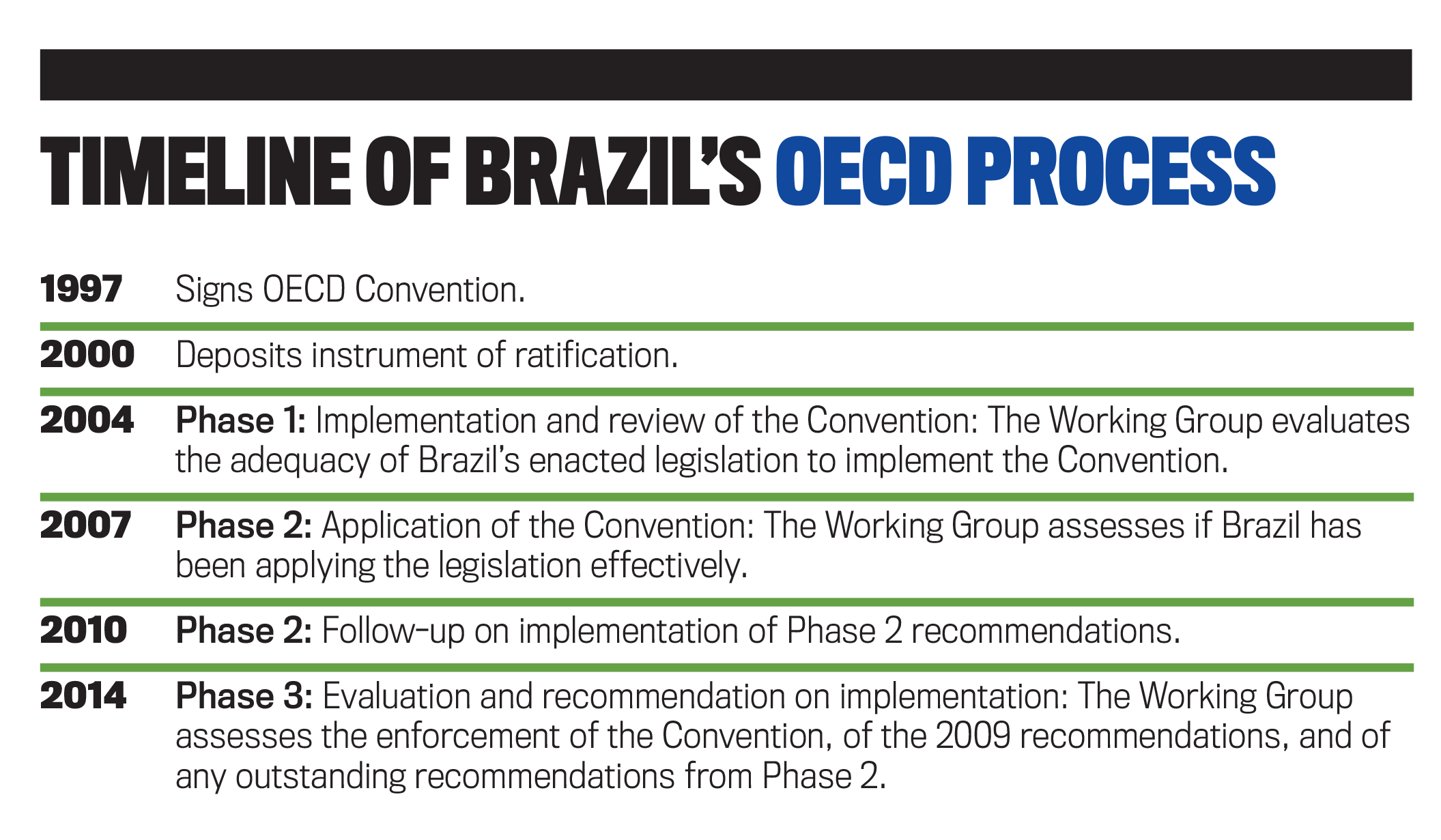

Brazil joined the OECD Antibribery Convention in 1997 to mitigate the increasing number of high-profile corruption scandals within the public and private sectors as well as the federal government and national congress. It was one of six non-OECD member countries that deposited its instrument of ratification on August 24, 2000.

The members of the OECD Antibribery Convention recognized that bribery is widespread among developing countries, distorting international market conditions. The Convention deemed that nations working individually couldn’t make the sweeping reforms needed to affect the competitive landscape on a global scale. What was needed was cooperation among nations. The agreement is based on the fundamental principle that bribery of a foreign official in international business transactions is a crime. This would make it illegal for companies based in that country to bribe public officials in developing countries. To that end, countries that sign onto the OECD Convention must integrate its provisions into their domestic legislation and are subject to a peer review monitoring process that ensures proper compliance and implementation.

The most recent advancements for the Convention are the 2011 OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the 2009 Antibribery Recommendations, which standardize and strengthen the regulatory controls that should be devised and how members should approach their anticorruption efforts. Essentially, they serve as a framework for leveling the regulatory playing field.

By 2009, Brazil had adopted the OECD recommendations to further combat bribery of foreign public officials in international business transactions. The recommendations were introduced to enhance the ability of the 40 members of the Convention to prevent, detect, and investigate allegations of foreign bribery, and they include guidance on best practices for internal controls, ethics, and compliance.

The OECD Antibribery Convention compels Brazil and the other signatories to take measures that establish the criminalization of bribery offenses and legally binding standards and to take related measures to efficiently fight the bribery of foreign public officials in international business transactions. But the OECD itself doesn’t have the ability to sanction or impose fines on Brazilian companies that break the Convention. Instead, it uses a “name and shame” peer review process to pressure governments to introduce legislation and implement it. The peer review process currently consists of three phases that monitor the implementation and enforcement of the Convention: evaluate if a country’s legislation is in conformance with the Convention (Phase 1), assess the effectiveness of the legislation (Phase 2), and assess enforcement of the legislation (Phase 3).

Peer Review Process

Prior to joining the Antibribery Convention, Brazil had a number of laws in place that made active bribery of public officials a criminal offense, made it illegal for a public official to accept a bribe, and addressed issues related to criminal organizations, money laundering, and concealment of assets. By entering the Convention, the country committed to enacting additional laws that reflected the provisions of the Convention.

During Phase 1 of the review process, the OECD Working Group reported that Brazil’s enactment of the Convention into domestic law by Decree No. 3,678 in 2000 and Law No. 10,467 in 2002 was consistent with the provisions of the Convention. The Working Group also found that the accounting rules and standards in the Civil Code, in the Federal Securities Commission, and in the tax code were sufficient to prohibit and penalize the production of fraudulent accounts. But there were still some issues that needed to be addressed in the implementation process, including (1) inconsistencies in the definition of a foreign public official in some articles of the legislation; (2) absence of criminal liability for legal entities; (3) absence of case law applying penalties to domestic bribery; (4) the need to determine if the agreements for mutual assistance with other countries allowed access to evidence in foreign jurisdictions; and (5) lack of specificity in the provisions forbidding the deduction of illegal payments.

Phase 2 of the review process reexamined the issues pending from Phase 1. The report (see http://bit.ly/2jHwFtc) commended Brazil on some developments to fight foreign bribery, such as the use of enhanced techniques to investigate complex bribery cases and efforts to report money laundering cases. The Working Group still had reservations and made recommendations to ensure the prevention and detection of bribery of foreign public officials, as well as the investigation, prosecution, and sanctioning of foreign bribery and related offenses.

The Working Group urged local authorities to require large companies to provide audited consolidated financial statements. This is particularly important in Brazil because few of the larger companies are publicly listed. Instead, many are state- or family-owned, which means they aren’t subject to the strict accountancy, reporting, and disclosure requirements of listed companies. Moreover, OECD lead examiners were left with the impression that the management and supervisory boards of many of these large companies overlooked the promotion of high standards of ethical conduct and compliance programs to prevent bribery.

The Working Group underlined the need to increase awareness of foreign bribery in both the public and private sectors and to incorporate proactive plans aimed at the prevention and detection of foreign bribery, including creation of strong internal control systems. More importantly, it determined that Brazil hadn’t taken sufficient steps to establish legal responsibility of legal entities and that the lack of sufficient penalties for legal entities engaged in bribery was a matter of urgency. Although there were visible enforcement efforts to fight domestic corruption, enforcement of foreign corruption was still lacking. According to the Working Group, the pertinent authorities hadn’t been provided the necessary resources and training that would enable them to increase their enforcement efforts.

The Working Group was very pleased with Brazil’s responses during the oral follow-up to Phase 2. Out of the 16 recommendations made during Phase 2, Brazil had fully implemented eight and partially implemented four. Brazil showed significant progress in the area of training and raising awareness of foreign bribery and in detecting and reporting foreign bribery and fraud. There also were three new “Brazilian Technical Standards for Independent Audits” that obliged auditors to report managers’ and company officials’ illegal acts and to report any failures to comply with regulations.

On the negative side, the Working Group noted that Brazil hadn’t investigated or prosecuted any foreign bribery cases but that it had taken steps to aid local authorities in their prosecution of such cases. The lack of legislation recognizing criminal liability for legal entities engaged in foreign bribery has been and continues to be one of the major concerns of the Working Group since the beginning of the peer review process. The committee emphatically noted that this legislation hadn’t been enacted and that it needed immediate attention.

Phase 3 of the review process presents the latest evaluations and recommendations on Brazil’s implementation and enforcement of the Convention based on progress made since Phase 2. Brazil completed Phase 3 in 2014. The Working Group praised Brazil for passing Corporate Liability Law No. 12,846, also known as the Clean Companies Act, on August 1, 2013. The new law finally puts Brazil in compliance with Article 2 of the Antibribery Convention regarding the liability of legal persons for bribery offenses.

Despite this achievement, serious concerns remain about the slow progress in enforcing antibribery regulations and the lack of clarity on how the Clean Companies Act explicitly covers state-owned enterprises (SOE) as legal entities. The report makes many recommendations for improvements in the areas of training, guidance, and cooperation among enforcement authorities. Within the area of prevention and detection, the Working Group was forceful about the need to urge companies to: establish standards of conduct and controls aimed specifically at foreign operations; create effective and independent monitoring bodies; and disclose firms’ prevention and detection internal compliance programs in annual reports.

The Clean Companies Act

In 2013, a wave of protesters took to the streets of Brazil to voice their concerns against the World Cup being held in the country. Complaints included the high costs of the stadiums, corruption, police brutality, and evictions connected to the preparation for the World Cup events. That same year, the prominent Mensalão case, which involved payments in the form of bribes to several high-profile politicians, was reopened. In light of public discontent and pressure from the OECD Working Group for legislation that imposed penalties to legal entities and for stronger enforcement, then-President Dilma Rousseff signed into law the Clean Companies Act in 2013.

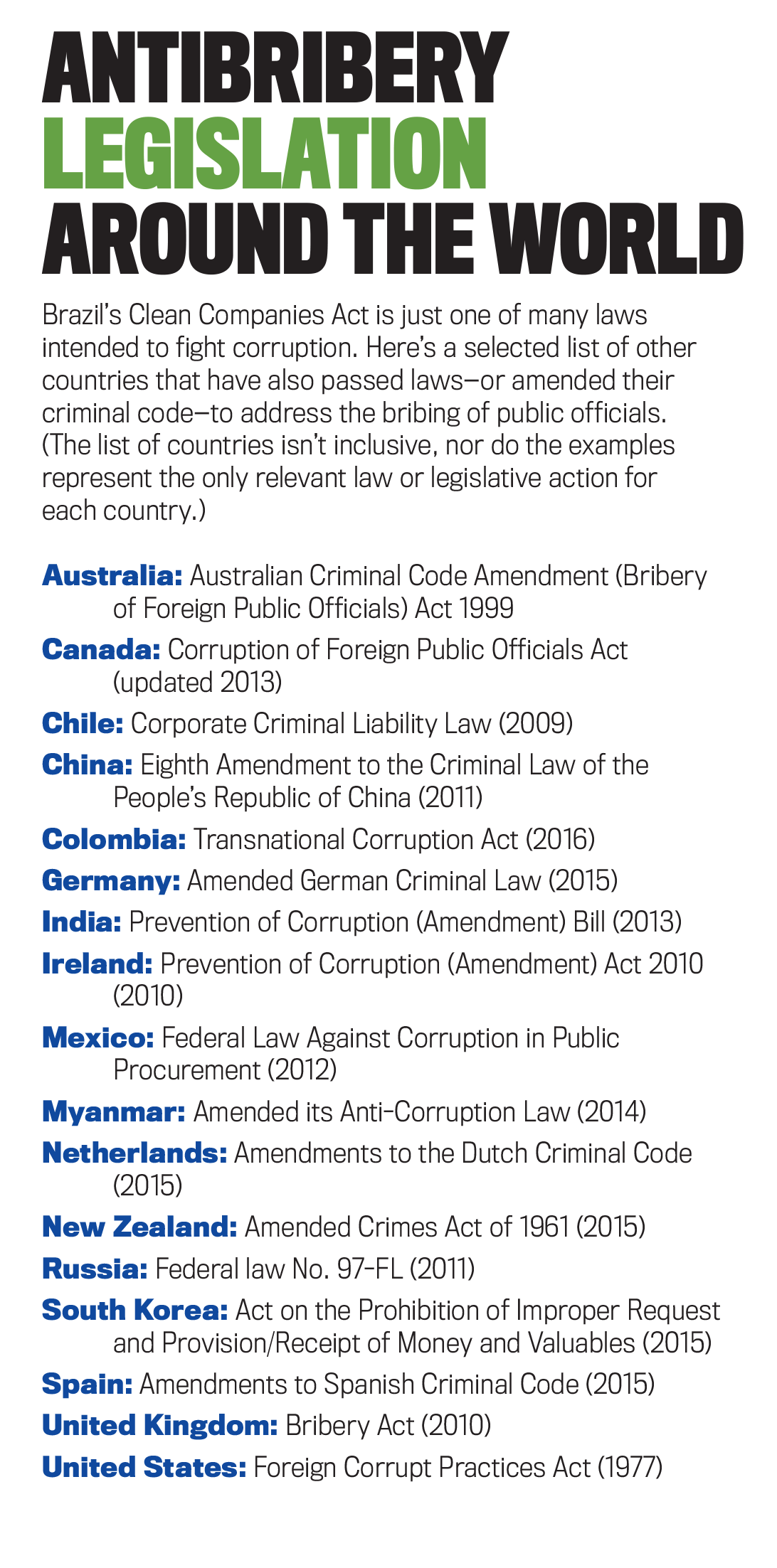

As noted, the Clean Companies Act represents one of the biggest steps in Brazil’s antibribery efforts. The law became effective at the beginning of 2014 and for the first time imposed civil and administrative liability on legal persons. The law applies to Brazilian and foreign companies operating in Brazil, even if temporarily, and some legal experts say that the Clean Companies Act meets and exceeds some of the Convention’s provisions and even some of the U.S. and U.K. laws. (For example, see Sonia Zaheer’s 2014 article, “Brazil’s Landmark Clean Companies Act: Comparison to the OECD Anti-bribery Convention and Issues,” in the Pacific McGeorge Global Business & Development Law Journal.)

The Clean Companies Act differs from similar antibribery laws in that it makes an individual or legal person liable without the need to prove intent to commit the bribery; it extends responsibility to all parties employed or hired by a company, including subsidiaries and consultants; and compliance programs must be in Portuguese. The Act expands the OECD’s definition of bribery to include both foreign and domestic officials. Unlike the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in the U.S., the Clean Companies Act also expands the scope of the offense to include facilitation of payments. The fines for bribery offenses can be substantial and can be as large as 20% of a firm’s gross revenue, or $25 million in some cases. Under the terms of the Act, strong internal controls and programs don’t constitute a defense but are simply considered a mitigating factor. Additionally, the law gives courts the power to dissolve legal entities involved in more serious violations.

The impact of the Clean Companies Act is expected to be minimal on multinationals that already are in conformity with the FCPA or the U.K. Bribery Act. But the effect will be considerable on employees of corporations that don’t already have anticorruption compliance programs in place. For example, the law could create tensions between Brazil and China, one of its largest trading partners, by forcing Chinese companies to step up their compliance programs.

AN ONGOING FIGHT AGAINST CORRUPTION

The adoption of the OECD Convention and the existence of antibribery laws in Brazil constitute an important milestone in the fight against corruption and in enhancing the country’s transparency. The latest reports show that Brazil has made considerable progress toward the goals of the Convention. Many believe that these changes are essential for the country to maintain its global competitive position in attracting foreign investment. Based on the latest report of the Working Group and on the reports from Transparency International, however, Brazil’s enforcement of antibribery laws continues to be a problem. Unless government officials make it a priority to investigate and prosecute bribery cases, the business community will remain skeptical of the country’s commitment to combating bribery and corruption.

Until Brazilian authorities step up their enforcement of antibribery laws, companies doing business in the country must weigh the benefits of investing in one of the largest developing economies against the impact that the high risk of corruption could have on operations. Accordingly, companies must prepare by implementing strong compliance programs that minimize the risks of corruption and of regulatory actions. These measures may include the promotion of ethical practices, implementation of strong governance structures, and the establishment of an independent internal audit function and of internal control systems that prevent and control corruption within the organization.

March 2017